One day last fall, a seventh-grade boy at Highland Park Middle School approached a classmate and told her he was writing a book about her. At first, the girl—let’s call her Abby—was flattered. Sweet, pretty, and involved in student government and athletics, Abby has never struggled socially. The boy—we’ll call him Richard—isn’t into things like sports, even though Highland Park is a place where, as one HPMS parent puts it, “athletic ability is currency.” But the boy is quick-witted and has a biting sense of humor that makes even his teachers laugh.

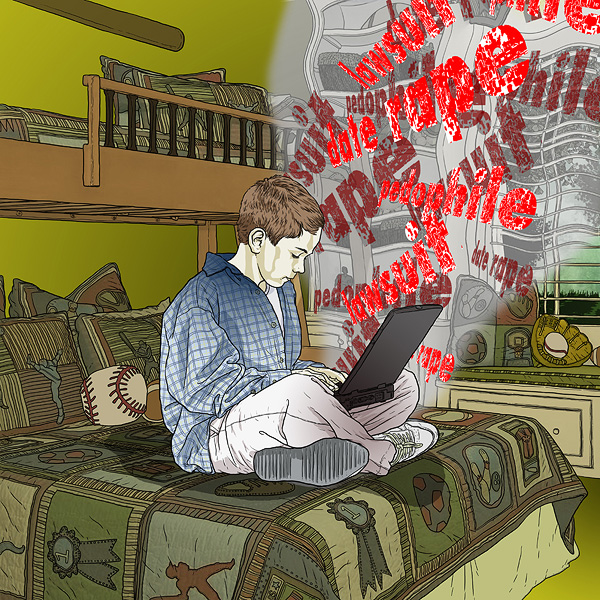

A few weeks after he told her about the book, Richard approached Abby again and told her that in his book, her character would get date raped. A lawsuit would later claim that Abby “could not have possibly comprehended the extent to which horrific acts would be carried out.” At the time, though, all she said was “Oh, okay.” She expected the book might be something like three pages handwritten in a notebook.

Everyone was shocked when, after a year of work, 14-year-old Richard produced a hardbound, 362-page novel called Nobody’s Perfect. It had a copyright and a slick black book jacket with a photo of the author and several endorsement blurbs from other students at Highland Park Middle School. “Breathtaking!” reads one. “An exhilarating ride from start to finish.” He’d published it himself through the site Lulu.com, with the first five copies going to his parents.

The book, set in Highland Park High School, tells the story of a sweet, pretty, popular girl and her circle of drinking, drugging, sex-crazed peers. Passive and insecure, Abby’s character is eventually drugged and date raped. She ends up prostituting herself before becoming homecoming queen.

To be clear, Abby is not this girl’s real name. Because minors are involved, we’ve changed their names. But Richard did not. In Nobody’s Perfect, he used the full names of more than 20 students and at least one teacher, whom he calls in the book “the biggest pedophile ever.”

At the beginning of eighth grade this year, Richard brought his novel to school to show the other kids what he’d done. His classmates were delighted by the salaciousness of it all. Out came the phone cameras. Soon some of the dirtiest pages found a photocopier. At least one student ordered a copy of the book online before the links were taken down.

When Abby’s mother got a copy of the book, she was deeply disturbed. But she’d known Richard since he was in kindergarten, so she did what most mothers would do. She called the kid’s parents and explained how upset she was. The families met. Abby’s mom asked that every copy of the book be destroyed. The way she saw it, the book was a literary form of bullying. She told Richard’s parents that she wanted a specialist to search every computer Richard had worked on, to delete the files and track down anyone else to whom he may have sent copies.

As sometimes happens in places like Highland Park, an amicable discussion soon degenerated into a lawsuit. The complaint, which was filed in September by an attorney friend of Abby’s mom, alleges that the book has caused Abby “permanent harm to the spirit and mind” and that though the depiction of her is false, “her reputation has been permanently damaged by scenes in the book that are too graphic and vile to be included in this filing.” The suit also claims that Richard’s parents, both high-profile doctors and professors, now divorced and rarely seen in the same room with each other, were negligent in letting their son write such a book.

Word of the book spread from the hallways of the middle school to the aisles of the grocery stores, and the lawsuit became the talk of the Park Cities. A group of mothers got together for a regular book club meeting not long after the news broke. Though they’d all done the assigned reading, all they wanted to discuss was Nobody’s Perfect.

If the case goes to court, young Richard’s notoriety may spread beyond Dallas. There is no precedent case law when it comes to middle-school children writing full-length, potentially defamatory novels about their classmates. Most recent libel cases don’t bode well for the plaintiffs, though, says Chip Stewart, assistant professor of media law at the Schieffer School of Journalism at TCU. To prove libel, a person has to demonstrate that the writer recklessly published a false and defamatory statement that hurt the plaintiff’s reputation. Those elements may not be so clear cut in this case, says Stewart, who also has a law degree. “A case like this would most likely turn on the question of how much free speech we are going to afford somebody before somebody else suffers harm from it,” he says.

Richard did take precautions. The characters in the book are all three years older. There’s an acknowledgments page at the front of the book noting that everything in the book is fiction. He also thanks Abby for “agreeing to have such horrible things done to her in the book.”

The accusation about intentional infliction of emotional distress has a much leaner burden of proof. For that allegation, a plaintiff has to prove only that the statements are outrageous by the standards of the community and so offensive that they could seriously harm someone. “If this isn’t an intentional infliction of distress, I don’t know what is,” Stewart says.

That’s not how parents who know both children see it. Richard is a good kid, they say. He goes to church even when his parents don’t. He didn’t want to hurt anyone. He just wanted attention. Many parents say he used real names only because he thought that would get more people to read his book. Every author wants to be read. He never expected blowback like this.

There is another factor at play here as well. The Park Cities have always been a mix of the wealthy and the merely upper middle class, those families who could have four bedrooms and a swimming pool in Plano but choose instead to live in what are affectionately called “cottages” in order to get their kids into the Highland Park Independent School District. Richard’s parents are among the more affluent. Abby’s parents are not.

At least one adult did warn Richard not to publish the real names beforehand. The mother of one of Richard’s best friends—a woman who also happens to be good friends with Abby’s mother—took Richard on a family vacation to Nantucket this summer. Richard brought along 100 pages of his manuscript, hoping to have his friend proofread. When his friend’s mom found out he was using real names, she lectured Richard for 10 minutes about why he shouldn’t do that. But it was to no avail.

Of course, Texas has a long history of authors excoriating their hometowns in book form. Just this summer, Larry McMurtry told a crowd in Archer City that The Last Picture Show, the work that thrust him into the national spotlight, was a “spiteful” book, intended to “lance some of the poisons of small-town life.” More recently, there was Dallas socialite Kim Gatlin’s book-turned-TV show, Good Christian Bitches, which takes on the backstabbing housewives of Texas. They pulled back the curtain, but none of those authors used real names.

This, it turns out, is Richard’s third novel. His first was about a cannibal clown, and his second was a reimagining of the Friday the 13th movies. As a writer, he is both dark and prolific. Nobody’s Perfect has plenty of spelling and syntax issues, but a lot of the writing is good. Richard has a strong sense of how to tell a story, of how characters develop over time. It’s better than some of the books on shelves right

now.

Even Abby’s mom describes the boy as a “genius.” Something of a writer herself, she doesn’t want to discourage a kid’s natural creativity, but reading about such horrific things being done to her daughter is unsettling. To her, it has the tone of Columbine.

With the case pending, neither family wants to comment on the record. There is talk of a potential countersuit. Parents of other kids named in the book have discussed taking legal action, but many of them feel like public lawsuits only make the situation worse—like this is the kind of thing best settled over a kitchen table.

Citing laws prohibiting the discussion of disciplinary action, the school district isn’t saying much publicly either. Richard served four days of in-school suspension for bringing the book to school, then rejoined his classes. A district spokesperson noted that the lawsuit is “a private matter between the litigants.”

The final chapter in this story is yet to be written. What’s undeniable is that all the adults involved want to protect their children. Abby’s mom has noticed subtle changes in her daughter recently, insecurities that weren’t there before. She hopes Abby hasn’t lost some part of her innocence over this. And since this has all fallen out, some of the kids at school have started picking on Richard, trying to make him feel bad about his desire to be a writer. It’s a shame, too. When this is all over, he’ll have some good material for a book.

Write to [email protected].