My neighborhood in Oak Cliff is overrun with puppies. It’s the most adorable infestation ever. You see them running in the streets, ducking under porches, playing with school kids waiting for the bus. You never know when you’ll come home to find a pack of soft, fuzzy puppies hanging out by your front door, wagging their little puppy tails, looking up at you with their little puppy eyes.

It sounds swell—until you spend a few nights staring at the ceiling, kept awake by dozens of puppies howling ceaselessly at nothing. And, of course, in a few months they won’t be puppies anymore. Left on the street, they’ll eventually turn nasty, like the wild Rottweiler my fiancée encountered while out for a run not long ago. There aren’t a lot of happy endings for dogs like that.

No one who cares about animals should want this for our city. As sad as it is, this problem is not new to Dallas. For decades, a combination of animal control officers, local shelters, rescue groups, and a number of commissions have struggled with the stray dog problem. But there’s something the city has never tried: a moratorium on commercial dog sales. I suggest the conversation begin with 36 months and see where it goes from there.

If the idea of making illegal that puppy in the window seems like a radical notion, you should know that Dallas wouldn’t be the first city in Texas to pass such a law. Austin’s city council approved a ban on retail pet sales in 2010. Albuquerque, New Mexico, and several California cities have similar laws on the books.

Here’s why a ban on puppy sales might help: shelters around North Texas are full. Like a lot of places, the Humane Society of Dallas County is well over capacity, with staff and volunteers “fostering” dogs at home to make room. The shelter adopts out, on average, one dog per week. Every day employees have to turn away people bringing them dogs—often entire litters of puppies they thought they’d be able to sell.

“We try to direct people to breed-specific rescue organizations,” says Cynthia Brown, the assistant director at the shelter. “I always advise them to research other no-kill shelters.”

Meanwhile, plenty of people in Dallas are willing to spend hundreds—sometimes thousands—of dollars on commercially bred puppies. Whether operating from a temporary setup in a parking lot or through the dozens of classifieds each week advertising designer puppies for sale, sellers rarely collect sales taxes or report earnings.

“People see a puppy for sale and they just get emotional,” says Nicole Paquette, Texas senior state director for the Humane Society of the United States. “Puppies are very cute, and people have this idea that they’re saving the puppy. But what you’re really doing is freeing up that spot for another puppy to get sold and pumping money back into the system that ultimately harms these dogs.”

The Texas Legislature passed a law aimed at eliminating puppy mills just this year. But dog breeders have as many lobbyists as they do puppies. The bill has a very loose definition of what constitutes a puppy mill and doesn’t address businesses with up to 11 active breeding females—that’s upwards of 60 puppies at a time. If, as a society, we really want to abolish puppy mills and irresponsible breeders, we have to deincentivize them. We have to cut off the money source.

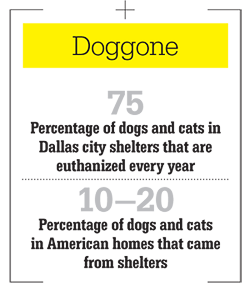

The city has ordinances about spaying and neutering, breeder licensing, and where you can and can’t sell dogs. But the laws are rarely enforced, and when they are, punishments are lenient. There’s even a new task force dedicated to eventually making Dallas a no-kill city. The members have a long way to go. In the fiscal year ending September 30, Dallas euthanized 14,732 dogs. That’s actually down from the year before, when the city killed 16,393 dogs. (In those years, the city killed 5,952 and 7,032 cats. We could ban sales of cats, too, but wild cats don’t attack people. They aren’t as big a problem.)

Only 10 to 20 percent of the dogs in American homes came from shelters. Though more people are feeling a sense of shame for not adopting, Bias thinks shelters have a bad reputation. “People think the dogs in shelters are broken animals,” he says. “That’s at least partially because all the stories coming out of shelters are about us fixing some broken animal. But you’d be surprised at what kinds of dogs you can adopt at a shelter. Lots of purebreds. Lots of designer dogs people let go. All of them needing welcoming homes.”

With no more puppies for sale, those adorable little creatures on my street will go up significantly in value. In a perfect world, with a moratorium in place, anyone who wanted a dog goes to a shelter or rescue organization and picks one out. The shelters cycle through dogs and effectively remove the stray puppies from the streets. With more adoption fees collected, those budget woes will also take care of themselves.

To be clear, what we’re not talking about with this ban is the increasingly elusive “responsible breeder,” like the individual trying only to preserve a show dog’s bloodline. We’re not talking about those people recouping the small cost of breeding. Those people probably aren’t contributing to pet overpopulation. No, we’re talking about people who are in the antiquated business of breeding dogs.

Now, I’m not naïve. I know there will always be some bad pet owners, just like there will always be some bad drivers and some bad

parents. There will always be stray dogs. But this could at least get a dialogue started. It could change the way people think of commercially bred dogs and where they should go when they’re adding a four-legged family member. So let’s pass a moratorium on dog sales. Let’s stiffen the penalties and beef up enforcement. Let’s direct consumers to shelters with policy and see how it works.

Of course, in these polarized political times, it’s important to point out that what I’m suggesting—a three-year ban on commercial pet sales—isn’t about restricting personal freedom. It’s about responsibility. In parental parlance, Dallas can get more puppies, but only after the city has shown we can take care of the ones we already have. Until then, if you really want a puppy that badly, just come to my neighborhood and pick one up.

Write to [email protected].