“I always like to use O.J. Simpson as an example,” he says. “A lot of folks who look like us like to say he was innocent.” He pauses. “But let’s be honest—he was guilty.” It gets a huge laugh. After it dies down, Watkins turns serious. “Why was he found not guilty? Because the jury was made up of people who look like us. I don’t want an O.J. in Dallas County.”

He speaks for a few minutes more, periodically eliciting murmured mmm-hmms from around the room.

“I need C.O. Bradford because I’m standing by myself,” he concludes. “And it’s lonely. I need someone to help bring justice to Texas.”

Unfortunately, it won’t be Bradford. In November, he’ll be narrowly defeated by a Republican former felony court judge, Pat Lykos. Watkins is still the only black district attorney in Texas.

It’s September 4. We’re back in Watkins’ office. We’re talking about the Memo Agreement plan, a diversion program for first-time offenders that’s similar to the county’s drug court, which favors rehab over jail. Begun in June 2007, the program allows for the dismissal of certain misdemeanors if the perpetrator does 24 to 30 hours of community service, takes a few classes, pays court costs, and keeps his nose clean for 60 days.

“If you convict them of that crime, you may very well be affecting their ability to get a job—a good job—for the rest of their life,” Terri Moore, Watkins’ first assistant, told me a couple of months ago. “Right? In which case, have you really done anything for your community or have you just helped somebody to stay down? If you’re 18, or if you’re 25, for that matter, and you shoplifted, I know if I’m an employer and I see that you have a record for theft, I’m not going to hire you.”

This is one of the under-publicized good ideas Watkins brought to bear on the DA’s office, not as headline-worthy as the exonerations or double-blind lineups, maybe, but still a solid building block of a reconstructed system. He should enjoy discussing the topic, the interview equivalent of a fastball down the middle of the plate. Only he can’t see the pitch. Again, he can’t help himself.

He mentions that “a certain individual on the commissioners court” (he eventually names Ken Mayfield) tried to torpedo the program, inviting in a municipal court judge and a police officer to talk about all the dismissed cases. Watkins countered by pulling the numbers and explaining the Memo Agreement. “They went home with their tail between their legs,” he says. “They pretty much went out the door saying, ‘I’m sorry.’ ”

Watkins has come to terms with the media, for the most part. He is coming to terms with the history of the DA’s office and the legacy of Henry Wade. He focuses on the future now rather than the past. But he has yet to come to terms with those who seek to knock him off stride in the name of politics. He has too much at stake.

Behind his desk, on a wall in the corner, there hangs a charcoal drawing depicting Watkins being sworn in as DA by retired judge L.A. Bedford, a legendary black attorney who led legal fights to desegregate Dallas schools. Bedford is a “first,” too—the first black judge in the city. The connection between the two runs even deeper: both went to Prairie View A&M, and Bedford was a deacon at the church Watkins grew up in. The drawing depicts a moment that is even more important than it appears. It is perhaps the key to all of this, the reason why he has the tendency, at times, to react poorly to people like Mayfield.

“I was looking at him when he was swearing me in, and he was trembling and he was almost teary-eyed,” Watkins says. “I was like, why is he so emotional for me? And then I realized: all the struggles that he had been through were really for me to have this opportunity. He said at the end of his little thing, ‘You’re the first. Let’s make sure that you’re not the last.’ I really didn’t understand at the time what he was talking about, but I understand it now. Any little thing you do will jeopardize someone else that may be different—a woman, Hispanic, whatever—to be put in this position. Whatever you do, if you make the smallest mistake, it will shine a disparaging light on everybody else that comes.”

You can hear it in his voice. Watkins physically feels that responsibility, senses the weight of it. The pressure he feels—not just as a district attorney, or even as the county and state’s first black district attorney—comes from knowing that everything he does will echo for years, affecting the lives of people who might not have even been born yet. When you’re in that position, carrying that burden, every pebble in the road has the potential to trip you up.

He is getting better at dealing with the scrutiny. He talks to Royce West. He talks to County Commissioner John Wiley Price. Their advice always comes too late, he jokes, but those post-mortem sessions have helped speed up his learning process, his evolution.

“You have to understand it’s not just about coming to work every day and doing your job,” he says. “That’s probably 10 percent of it.”

It’s November 4, and Craig Watkins is onstage in the middle of the Bishop Arts District, celebrating the victory of Barack Obama with just about every Democratic elected official in the county. It brings to mind something he said about Obama months ago in his office, just after the Texas primary.

“When I first met him, when I first saw all this, when he first started running, I’m thinking to myself, Obama is a United States senator,” he said. “He’s been there two years. He has a book out. Is this an opportunity for him to sell a whole bunch of books, to lay a stake on his claim to be a United States senator from Illinois for whenever he wants to quit [the race]? But I didn’t see that he may be our president. I just thought it was calculated on his part to put himself in a position where he wouldn’t have any serious challengers for his position in the future.”

Watkins’ detractors—some of these people are attorneys within his own office, folks still loyal to the man Watkins defeated, Toby Shook—say much the same thing about him. They claim that he lucked into a high-profile issue, the exonerations, and now he is using it for his own political gain. That he is not serious about being the district attorney. That he is not campaigning for justice but for another office. Off the record, they say he spends more time out politicking than inside the DA’s office working. On the record, people like Shook say that he is a good headline with no story.

“My frustration is, the majority of those exonerations were done under Bill Hill, and the first few that he did were already being worked on by Bill Hill,” Shook says. “The way that’s been played—it’s not only Craig’s fault. I think the media has jumped on that. But I think he’s obviously, being a politician, he’s gained from that. He plays that up.”

Shook, of course, expected to be sitting where Watkins is and says he’s “not sure” whether he’ll run against Watkins next year. But he worked at the DA’s office too long not to retain a handle on the situation inside Frank Crowley.

“The way it’s played up, I think it really hurt the morale of his office, and the prosecutors there,” he says. He points out that most of the exoneration cases came from the 1970s and ’80s. “Because it’s been played up almost to the extent of, ‘All these [prosecutors] are bad actors.’ They weren’t even born, or they were 5 years old when those cases were going on.”

Shook won’t say much more. “I’ve got to be kind of careful here, because practicing criminal law—he’s kind of sensitive to criticism.”

Watkins’ evolution has affected the way he interacts with his own staff. When he took office, there were people who still had portraits of Henry Wade hanging in their offices. Watkins was an outsider, someone who had just defeated a man they had worked with for years, someone they liked and supported. “At that point,” he says, “you have to look at it from the standpoint of: I can go in there and try to make these people like me. But is that a good use of my time?”

Instead of trying to make friends with the attorneys working for him, he has tried to win their respect. And he has gotten it, he says, because now they see. They see the change in the jury pools, now filled with people that trust and believe in the system. They see that the conviction integrity unit hasn’t put their jobs in danger; it’s made their jobs easier. Conviction rates have actually gotten higher. He points to the day at the courthouse when James Woodard was exonerated after spending 27 years in jail.

In a court across the hall, one of Watkins’ prosecutors was picking a jury panel. The prospective jurors were outside when Woodard walked out of his hearing and into a jubilant crowd. There was a commotion in the hall.

“After the exoneration, everybody comes up, raises Woodard’s hands, praises everybody: ‘We just freed an innocent man,’ ” Watkins says. “This prosecutor across the hall is thinking, ‘God, maybe I need to get rid of this jury panel because they may be swayed by what they just saw. It would be hard for me to convince this jury to convict this guilty person.’ That’s what he’s thinking, but he went through with it. He said the jury took five minutes to come back with a conviction. It’s because credibility has been restored. People are starting to see it. They’re starting to get it.”

It’s November 6. Watkins is onstage again, this time in a small auditorium on the third floor of SMU’s Dallas Hall. He is on a panel to discuss writer Michael Hall’s story “The Exonerated,” as part of the university-sponsored Texas Monthly Live series. Next to him on the dais are Hall; The Innocence Project of Texas’ Michelle Moore; James Waller, one of the 19 wrongly convicted men set free in Dallas County since 2001; and Rick Halperin and Tony Pederson from SMU. Behind them, projected on a giant screen, is a group photo of most of the men who have been released from Texas prisons thanks to DNA evidence.

Watkins could use this as a victory lap; it’s partially what it is intended to be. Instead, he uses it as a reminder, to the audience and to himself, not to get too caught up in the headlines, in the successes so far. DNA tests can fix past mistakes, but they can’t prevent ones in the future. He points out that most of the DNA results come back positive. He talks about the downside of exonerations: you find the guy who actually did it, you can prove it, and there is nothing that can be done because of statutes of limitations. And you come face-to-face with the reality that the person who wasn’t arrested in the first place went on to commit more crimes.

Most notably, he takes a more measured tone when referring to previous administrations. He’s no longer the guy who came on the scene throwing bombs at Henry Wade and his followers. If anything, he sympathizes with him.

“Prosecutors 20 years ago weren’t bad people,” he says. “I don’t think Henry Wade was a bad man.” The Innocence Project’s Moore looks fairly incredulous at that, but Watkins presses on. No, he says, Wade had good intentions; he just “got lost.” Watkins is afraid of believing his own hype because he believes that’s what happened to Wade. “You always have to check yourself.”

It’s a new side of Watkins, less rebellious. More evolved. Here is a man who has stopped struggling with himself, who has an answer to his own question, “Am I gonna stoop to that level or am I gonna stay aboveboard and do what’s necessary to make all this right?” The answer is clear in his statesman-like demeanor tonight, and in the glimpses I’ve seen on a more regular basis over these past few months. The answer was always there; it was just hidden. It’s not about his ego, or any personal slight, real or perceived. It’s not about Craig Watkins at all. It’s about James Waller’s face when he walked out of jail as a free man. “It looked like he was seeing light for the first time,” he says. Every sling and arrow is worth that.

Two weeks later, Watkins calls me out of the blue. He has something on his mind, and he wasn’t sure if I caught it from the audience at SMU.

“When we were first talking, I can remember back then, I was really venting,” he says. “I was venting. I look back on that now and I kind of question my mentality, because I was dealing with a lot of anger I think.”

He’ll deal with more as long as he stays in politics—especially as he enters the next phase of his political maturation, Royce West says, and learns “the legislative process, and to impact the laws that he is duty-bound to enforce.” It’s unavoidable. The difference is, now he welcomes it. Criticism, he finally sees, isn’t standing in the way of where he wants to go. No, it’s what is keeping him on his path. He doesn’t look forward to it, of course, but without that periodic reality check, there might be an upstart district attorney 30 years from now piling the ruins of a broken system at his feet. Wade could have used more critics.

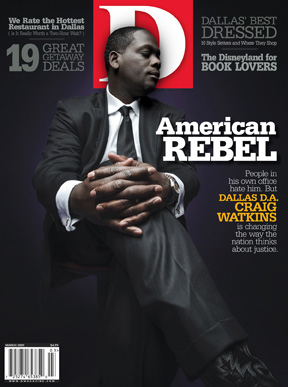

Watkins welcomes the criticism because he never wants to forget who he is. He’s a black district attorney who, though he has faced long odds and is often underestimated, strives for a significant change in The Way Things Are Done. He is, according to the Dallas Morning News, the 2008 Texan of the Year, someone who “has elevated the debate about the quality of justice and has altered our view of the job that district attorneys everywhere should do.” But he’s also just a man—a guy from South Dallas with a wife, three kids, and a mortgage.

“We make mistakes,” he says. “We do things that are wrong. But I think if you’re doing it with a good heart and good intentions and you make a mistake, people are more willing to forgive you and keep you in office and do things for you, as opposed to when you try to cover it up and to hide it. To try to make you out to be this person that needs to be put on this pedestal and be better than God—I think that’s what we had in the past with politicians locally. Admit your mistakes. Admit the problems that you had. And go on, because everybody has them.”