|

On our second date, which happened to be April Fool’s Day, we went to a Rangers game. We’d only known each other for a few weeks, having met through MySpace. By coincidence, Brandon had gone to Texas Tech with Gina’s cousin, whom he spotted in one of Gina’s pictures, on her profile. (Because we’re telling this story together, we’ll have to use our first names to keep things clear.) Brandon e-mailed Gina, and that’s how it started. When we met in person, we both felt like we’d known each other for years. Brandon thought Gina was strikingly beautiful but had a down-to-earth demeanor. Gina thought it was weird how easily she could talk to him, right away, and she shared his sarcastic sense of humor. At the baseball game, Brandon took a gamble. He had told her that night about an upcoming business trip in May to Palm Springs, California. He works as a financial advisor for Martin Financial Group in Dallas, which sells securities through a broker called Securian Financial Services, and every two years, Securian sends its top producers from across the country to a sales conference.

“Have you ever been to California?” Brandon asked Gina.

“Yes, a couple of times,” she replied.

“Would you want to go back sometime?” he asked.

“Oh, okay. Sure.” She figured the invitation was an April Fool’s joke.

He wasn’t kidding, and our fifth date was a trip to Palm Springs. That’s when we took a tram ride to the top of a mountain, got lost for three bitterly cold nights in the wilderness without food or shelter, were rescued thanks to some matches a dead man left on the mountain a year earlier—a miracle, really—and wound up on the Today show.

“The ad for the tram was three lines,” Brandon says. “‘Enjoy spectacular views, there’s a gift shop, restaurant, and bar.’ In all those newspaper stories and on TV afterward, they kept calling us day hikers. People would ask, ‘Why weren’t you prepared?’ My standard joke was ‘Well, I had my wallet. How else do you prepare for a bar?’”

One Very Wrong Turn

The night before we got lost, we had a blast. Close to 1,000 people from the sales conference filled a ballroom at the J.W. Marriott for Rat Pack Night, and after a few trips to the open bar, we hit the dance floor. Gina isn’t a great swing dancer, but Brandon knows how, and he told her, “Just follow my lead.” We didn’t go up to our room until 3 am.

Saturday morning was painful, as we had to get up at 7, after just four hours of sleep, to eat breakfast and hear the morning’s speaker. That session let out at 11, and we had a few hours to kill before dinner. The conference organizers had hired a travel company to give us some options: a safari through the desert in the back of a Jeep (only if we got to drive), a celebrity homes tour (boring), horseback riding (Brandon tried once and couldn’t find the steering wheel), golf (a waste of time, unless it’s for business), or a ride up Mount San Jacinto on the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway. By process of elimination, we went up the mountain.

Someone mentioned that it might be chilly at the top. San Jacinto is Southern California’s second-highest peak, at 10,804 feet. The tram rushes from the desert floor, at 2,643 feet, up to 8,516 feet in 10 minutes. The temperature can drop 30 degrees during the climb. Heeding the advice, Brandon changed out of his shorts and into wind pants, and Gina put on a pair of yoga capris. He wore a t-shirt while she opted for two layered tank tops, one of them bright orange. They both wore sneakers.

No one talked much on the tram. The ride was dizzying, because the floor of the car rotated to give all 40 passengers a 360-degree view of the steepest escarpment in North America. (The tram has starred in, among other movies, Skyway to Death (1974), Death Journey (1975), and Hanging by a Thread (1979). Its operators have apparently gone for a softer image lately. It appeared in the Food Channel’s $40 A Day in 2003 and the HDNet show Bikini Destinations in 2004.) Our ears popped repeatedly. Being an Iowa native, Gina was excited to see small patches of snow.

When the tram stopped and the doors opened, the guide said, “Be back here in two hours.” That was it. Everybody went his own way. We heard another passenger ask, “Where’s the bar?” and most people headed in that direction.

|

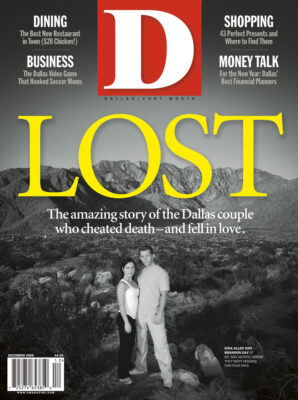

| NATURE LOVERS: Brandon and Gina had never even been camping before. |

We thought a walk would clear our sleepy heads, so, armed with just a digital camera, ChapStick, and a 1-ounce tube of sunscreen, we followed a paved path in the opposite direction. After about 100 yards, the path turned to dirt, and we saw hikers coming up the mountain toward us. They were wearing packs and using walking poles. Gina chuckled about all their gear. “What the hell is this?” she said. “These people are overdoing it.”

It was a beautiful, crisp day, about 60 degrees. As we wandered along the trail, around granite boulders and between evergreen trees, Gina found a patch of snow and started pelting Brandon with snowballs. She’s tiny, only 4-foot-11 and about 100 pounds. But the 24-year-old is the youngest of nine children, and her two closest siblings are boys, so she developed a competitive edge growing up.

Brandon, at 28, has about 60 pounds on her, but he wasn’t timid about returning fire. His high school years at Trinity in Euless were filled with football, baseball, and, because he was the eldest of three brothers, a lot of broken furniture.

At this point, the terrain was easy. You could have taken a 3-year-old with you, and it wouldn’t have been a problem. We saw a lookout point maybe 75 yards away, off the trail. We could see people there, and other people coming up the trail—casually dressed, wearing sneakers—said the view was pretty, so we headed off in that direction. And it was worth the detour. Looking down to the desert floor, two mountain ridges framed Palm Springs in the far distance, beneath our feet.

“Wait,” Gina said, “do you hear that?”

From somewhere in the distance came the whoosh of a waterfall—maybe 75 yards farther. Getting to it was a bit more difficult. We had to hoist ourselves over boulders, but we could still hear voices coming from back on the trail, and only 30 minutes had passed since we’d gotten off the tram. With the stops we’d made for pictures and snowball fights, we figured we’d be back at the bar in 15 minutes.

But somehow Brandon miscalculated and made a wrong turn on the way back. It was easier, when we came to a tree or boulder or some other obstacle, to turn right, down the mountain, rather than climb up. And so by small steps we became lost, a slight turn off course, followed by another, and another. We both noticed the terrain didn’t look familiar.

Finally, Gina spoke up. “Do you know where we are? Are we lost?” She was mostly teasing.

“No, a man is never lost,” Brandon said, his braggadocio only half in jest. “I have never been lost. I just haven’t found where I’m going yet.” We could still hear voices, coming from just over there. “It’ll be right around this corner,” Brandon said more than once.

But the voices were playing tricks on us, bouncing off boulders, echoing off steep canyon walls, leading us farther from the trail. And the next thing we knew, we were sliding on our butts over loose scree, holding onto brush for support. At this point, the joking was long behind us, and we really started to sense we were in trouble.

“I’m not sure I can do this,” Gina said.

“I’ll hold your hand,” Brandon said. “Just follow me. You can do this. Be careful. Watch your step. Don’t get hurt, and we’ll get out of this fine.”

But Brandon could see it in Gina’s face. She’s scared. Her hands are shaking. He knew she didn’t have any experience in the wilderness. She had never camped out or even done any real hiking. Neither had he, but he was confident. It wasn’t the mountain that worried him—it was Gina. Growing up without sisters, Brandon didn’t handle women crying very well.

Making it worse for Gina, she could feel herself losing it. She was worried about getting back to the tram, but she was just as worried about how Brandon would handle it if she gave up and started bawling. It would be easy for him to say, “You know what? Screw you then. You sit here, cry, be a baby. I’m getting out of here.” After all, he’d only known her a little over a month. So Gina pulled herself together and pressed on.

By 3:30, we decided to yell.

Gina pointed herself in different directions to make herself heard and shouted: “Help! Is there anyone there! We’re lost!”

Brandon still wasn’t ready to admit that. He yelled: “Is there anybody there?”

We’d go for 15 minutes, then stop and yell again. And the whole time, we kept thinking, There are hikers all over this mountain. Someone has to hear us. But the air at 8,500 feet was thin, making it difficult for us to catch our breath. And the terrain just got rockier. Each step created a small landslide. It was like one of those Chinese finger cuffs; the harder we struggled, the more we got stuck. And now the sun was slipping over the ridges of Mount San Jacinto.

Around 7:30, we were scrambling along a stream, the steep walls of the canyon standing on each side, when we came to a 50-foot waterfall. The temperature was plummeting. And we realized then that we were going to spend the night.

Huddled, Shivering, in Disbelief

Brandon found a big, flat rock near the water, out in the open, to make it easier for rescuers to spot us, and we sat there, running through reasons why people had to be looking for us. First off, we weren’t on the bus back to the Marriott; someone had to notice that. Then we wouldn’t be at dinner; people from Brandon’s firm would see the empty chairs. The next day, we wouldn’t be on our flight; Brandon’s roommate was supposed to pick us up at the airport. Each step was a failsafe, in our minds.

As Brandon was evaluating our circumstances, Gina began crying for the first time. How is this possible? How are we ever going live through a night out here? Brandon felt responsible for the mess we were in and started to apologize, but she stopped him. “We both walked off the path together. We’re here together. We’ll get out of this together,” she said.

|

| Brandon and Gina’s Journey From the top of the mountain, it looked to them like they could walk down to Palm Springs, almost due east. But once they got into Long Valley, the terrain was far more rugged than they imagined. And then Brandon and Gina got trapped. |

Brandon made a decision. He told Gina, “We are not going to die on this mountain.” That calmed her down a little, but Brandon could still see something was wrong. He held her and kept trying to comfort her. He said, “I know you’re scared, baby. I know you’re scared.”But this time it wasn’t fear he was seeing in her face. It was something else entirely. And despite their dire circumstances—or because of them—Gina made a decision of her own. She decided to share. “I know you don’t want to hear this right now,” she said, “but I really have to crap.” When he gave her a funny look, she added, “No, this is serious!”

That was the first time we laughed.

But there was really nowhere to go, so Brandon tried to keep her mind on something else. He mentioned Alive, the 1993 movie based on the true story of the Uruguayan rugby team that (mostly) survives a plane crash in the Andes only after turning to cannibalism. In a mock serious tone, Brandon told Gina: “I want you to know, if anything goes really wrong, you can eat me. It’s okay. You have my permission.”

By now, the temperature had dipped below 40, not counting wind chill. For a while, we tried banging two rocks together to generate sparks and light a fire, and then we tried spinning a stick between our palms. But we’d only seen that stuff on television, and the spray from the waterfall was getting the kindling wet. Gina started making Castaway jokes, shouting, “Wilson!” It was all we could do to take our minds off our situation and put our focus elsewhere.

With the wind picking up, Brandon said he’d seen a makeshift cave—more like a crevice created by three rocks. There was just enough room for us to sit hunched over, Gina’s legs wrapped around Brandon, hugging each other to conserve heat.

We didn’t sleep that night. The waterfall was loud, it was windy, and every 30 minutes, Brandon made us stand up and jog in place, so that our extremities wouldn’t go numb. We knew that if we couldn’t feel our extremities, our bodies were cutting that part off. When Brandon’s toes hurt, that was a good thing. When he couldn’t feel them, he knew it was time to get out and jog. Even having grown up Iowa, traipsing through howling wind and snow on her way to school, Gina couldn’t remember ever being that cold.

When we were huddled in the crevice, time stood still. Brandon would get lost in his thoughts, then check his watch in the moonlight and see that only 10 minutes had gone by.

“What should I think about?” Gina would ask, almost like a pestering little sister.

“I don’t know,” Brandon would say. “Think about a vacation you took. A favorite memory from being with your family. Anything.”

“What are you thinking about?”

“I’m not telling you what I’m thinking about!”

A New Plan

When the sun finally rose Sunday morning, we figured the worst was behind us. What a hell of a night. Weather like that could have killed us. But the worst was behind us. We’d always have the crazy story to tell about the time we had to spend the night on Mount San Jacinto. All we had to do was wait for rescuers to find us.

Brandon remembered something he’d heard: oftentimes people who are lost in the wilderness will wander farther away from the search area, making themselves harder to find. We agreed to stay put. The tour company that had organized the tram trip had to know we were missing. The search party was probably getting started with the rising sun.

We sat on a flat rock, above the waterfall, for three hours. We were thirsty, but we didn’t drink any water because we were worried about parasites, and we expected at any minute to hear a helicopter or maybe someone calling our names. But three hours passed without a sound except for the waterfall. And the horrible thought occurred to us: what if they aren’t searching? It was a good thing too, because as it turns out, they weren’t. We would later learn that the tour guide had assumed we’d found another way back to the hotel, after we didn’t make the roll call on the bus.

Concluding no one was looking for us, fortified only by the pieces of Orbit gum we’d been chewing since yesterday morning at the hotel, we came up with new strategy: we had taken a picture of the waterfall that led us off the path, so let’s go find it. Once we find that fall, we will know we’re close to the trail. Besides, up was the only direction we could go, because the waterfall below us was a dead end.

Before we left, we made a big “X” on the ground with rocks, and we left one of Gina’s tank tops by it, the bright orange one. We figured at least searchers would know which side of the mountain we were on.

Climbing up proved much more difficult than climbing down. The slope was so steep that we were forced to crawl on our bellies, using what we called the “dig and claw” method. Our mantra became “We are not dying on this mountain.” And then Gina recognized a lone dead pine tree that she thought resembled an old man. Yesterday from the scenic overlook, that tree had been above us. Now it was below, and off in the distance we could once again see Palm Springs. With what seemed like 100 waterfalls on that mountain, they all began to look the same. We must have missed ours. Another plan foiled.

But it hadn’t taken us that long to climb to the top of the ridge, so how long could it possibly take to hike all the way down to Palm Springs? The tram ride had only taken 10 minutes. We figured we couldn’t stay put. Now we were at a higher elevation than the night before, and we knew the danger of exposure. The wind would be unbearable. At the very least, at a lower elevation, it wouldn’t be as cold.

So we climbed up on a boulder and found a parallel valley that appeared to offer an alternate route around the 50-foot fall that trapped us the night before. We decided it was our best option.

The path we’d chosen forced us to do Class 3 and 4 climbing, when normally a rope would be used for protection. The hardest is Class 5, aka technical climbing. Brandon kept telling Gina: “Stay positive. Don’t worry about how far you have to go. Just think 10 feet at a time. Concentrate on your next two steps.”

At one point, Brandon came to a 10-foot vertical drop. He was perched on the edge, holding onto some roots for balance. Gina was about 20 yards above and behind him. He heard her scream and looked over his left shoulder to see a rock slide headed right at him. Brandon grabbed the root with both hands and swung off the edge of the cliff, dangling in midair. A rock the size of a suitcase missed him by a foot. We watched as the rock bounded down the mountain, snapping twigs.

We learned that day to stay closer together, so that if one of us started another slide, the rocks wouldn’t have time to build up momentum. Brandon, being a chess player, started strategizing each step of our made-up route. He tried to plan several moves in advance. In a way, he embraced the challenge.

That day, Sunday, was actually pleasant—given the circumstances. The weather was warm, and there was a slight breeze. Being at a lower elevation and among more trees really helped. Gina took off her second tank top and gave it to Brandon to tie around his head so his scalp wouldn’t get sunburned. We shared that one tube of sunscreen and used it sparingly on our noses and cheeks. Gina’s windbreaker was a little hot, but it was no big deal.

We’d sort of come to accept our plight. Saturday had been surreal—it seemed like something out of a movie. We just couldn’t believe what was happening to us. By Sunday, our unplanned adventure seemed to be turning into an accepted routine. At least we were making progress.

At about 5 o’clock, the valley we were following did merge (as we had hoped) with the valley we were stuck in the night before, and it reunited with the stream from the day before (as we had hoped). We had come to a point where Brandon decided we had to take water, parasites be damned. It was so cold that we didn’t even cup our hands to drink. We put our lips right to the water and slurped. And sitting back, we took in our beautiful surroundings.

We had the feeling that we were walking where no one else had ever walked before. The terrain was so rugged that we knew other hikers would never have come this way. It was strange to think that something so beautiful could also hold such danger.

But the water we drank also fed thick vegetation all around us: piñon pine, yellow pine, scrub oak, white fir, juniper, wild apricot. It was so thick in places that we had to crawl and fight our way through it. Branches cut into our arms and legs, making them bleed.

Toward the end of Sunday, Gina said it. Brandon was being so patient, showing her where to put her foot, encouraging her around huge boulders, slippery rocks and dead logs, and putting up with her stubborn competitiveness. The last straw came when she was leading the way and found her hand an inch away from a hairy spider. She screamed. He came to the rock, laughed that one spider had her in such a fit, and shooed it away. Then it just slipped out.

She blurted, “Goddamn it! I think I love you!” Almost as soon as the words left her mouth, she thought, I can’t believe I just said that.

After some awkward silence and about 30 feet of distance, Brandon said, “I love you, too. And we’re going to beat this thing together. Just stay focused.” He thought, Did she just say that because of stress? What was that about?

The sun was getting low, and Brandon had fallen into the stream when a log broke under his weight. So we decided to stop for the day. Again we found a flat rock, up against some boulders to protect us from the wind, which we knew would rush down the mountain as the desert floor cooled.

With Brandon’s feet and shoes wet, we prepared for another cold night. Gina gave her socks to him and put her sweaty, dirt-filled shoes on over bare feet. Again we huddled together and prepared to face another cold night. The second night wasn’t quite as cold as the first. Still, we got up periodically to run in place and get our blood flowing. And we chewed those same two pieces of Orbit gum all night. But now certainly people knew we were missing.

A Dead Man’s Campsite

Monday morning, Gina looked like hell. She’d taken her hair down each night as a wind block, and it was filled with bits of the mountain. Using Brandon’s sunglasses as a mirror, she saw that her lips were cracked. And they were so dirty that it looked like she was wearing black lip liner.

We picked ourselves up and kept going, certain that at each bend in the stream we’d see the base of the mountain, the city. But each bend brought yet more mountain. And black ants. Now, whenever we grabbed a branch or vine to help us climb down a boulder, we would look down and see our hands, arms, and ankles covered with biting ants. At one point, Brandon fell through a crevice in some rocks and twisted his ankle. He also nearly fell while repelling with a branch down a 15-foot cliff. As he was falling and flailing blindly, his left hand caught another branch, and he held on, probably saving his life.

The chaparral grew thicker, even harder to penetrate. But we also started to see cactus, so we figured we had to be getting close to the desert floor. We crossed the stream repeatedly, looking for easier ways to navigate, at one point having to strip down and wade across, carrying our clothes over our heads to keep them dry. And we stopped every hour, on the hour, to take water and rest.

Gina would tell him, “I do not want to spend another night on this mountain.” She was angry.

Around 5 o’clock, we had just come around another bend in the stream. The bush was so thick that we had to crawl. When Brandon stood up, he saw the campsite on the other side of the stream. A green poncho strung between two trees. A foam mat.

|

| WATERY GRAVE: John Donovan’s body was later found near this waterfall. |

“Come here, Gina. Look up. Right. There.”“Is that what I think?”

We started yelling. “Hello? Help! Anybody there? We’re lost!”

Someone else was there, someone with a phone or radio. We looked for a place to cross the stream. Brandon slipped and got wet again but at this point didn’t care.

When we got a closer look, though, there were signs that something was amiss. A dirty disposable razor lay in the dirt. A fork and a spoon, both rusty. Two sneakers lay 10 feet apart. We knew it hadn’t rained since we’d been on the mountain, so the implements had to have been exposed for weeks, maybe.

We spotted a backpack, at the water’s edge, and didn’t hesitate to tear into it. Inside, we found zipped pouches inside other zipped pouches. Medicine. Tent stakes. A bag of socks. A fleece pullover. A compass. A bag containing a wallet and ID. A small tin used for cooking.

And then we found the maps. Water quality maps. Topographic maps. They were on white copy paper and looked like they’d been faxed. And there were notes written all over them in the margins and white spaces. Picking a random entry, we started reading. The author said he was trapped in a gorge. Gina was disturbed because the stiff yet sloppy cursive writing looked like her dad’s. But then, over Brandon’s shoulder, she said, “Baby, look at this. No way! Somebody has to be around here because it’s dated today, May 8. Somebody has to be here!”

“Gina,” Brandon said, “that’s May 8, 2005.”

The journal was a year old. We realized then that something bad had happened where we stood. And we felt sick, like an end was near.

Gina stopped reading and began going through the other contents of the backpack. She found a prayer card for St. Christopher, the patron saint of travelers. She grew up Catholic and had been trying to remember St. Christopher’s prayer as we were coming down the mountain. She felt herself starting to shake and panic. And looking closer at the personal effects, she saw that the driver’s license and insurance were still current. He was about my father’s age, she thought. This was somebody’s dad. She prayed to St. Christopher aloud and wept.

Brandon kept reading the journal, looking for clues, anything that would help us. The man’s name was John Donovan, and he said he knew no one was looking for him. He was down to his last few crackers. In his last entry, dated May 14, he said he wanted to be buried in a VA cemetery. Then he wrote: “Goodbye and I love you all.”

Now terror was creeping into our hearts. A man with equipment and maps had died here, and we had nothing but those same maps and no way to use them. But what did Donovan mean about being trapped? What gorge was he talking about? And where was his body? Brandon did his best to maintain a positive attitude, but it was difficult. Looking at Donovan’s ID, he told Gina, “This guy was 60 years old. Maybe he had a heart problem. Maybe he fell and broke something.”

We decided to leave the backpack. It was wet and heavy. But we kept Donovan’s personal effects: his driver’s license, glasses, and other identifying papers, thinking his family would want them. And we kept moving.

We came to another waterfall, this one about 25 feet, but we were able to climb around it. Fifty yards farther, though, we found another waterfall, this one 100 feet. The water crashed into the face of a cliff that probably dropped, overall, 300 feet. The canyon walls at this point climbed nearly straight up.

And now Donovan’s journal made sense.

Looking over the waterfall, Gina said in disbelief, “Are you kidding me?”

One thing we told each other repeatedly coming down the mountain was that we were in control of our own destiny. Be smart. Be careful. Think things through, and we would make it out. Now we knew that wasn’t true. Going back the way we came wasn’t an option. Even if we weren’t so exhausted, even if we had something to eat, we had slid and dropped down rock faces that we knew we couldn’t climb back up. Now the mountain was in control. We were trapped.

So we returned to Donovan’s campsite to see if there was anything else there to help the cause. In her haste and amid all the bags zipped inside each other, Gina had missed about 25 strike-anywhere matches. This time we took the backpack, the foam mat, the poncho, and we returned to the waterfall. We found a small perch up on the canyon wall, above the trees, to make ourselves visible.

Gina put on Donovan’s fleece and laid out some of his wet socks on the rocks. She set up Donovan’s poncho as a screen, preparing for the wind to come down the mountain at night.

The sun was beginning to set and Brandon set to making a signal fire. Every stick he picked up was like kindling, and he realized that if he lit a signal fire beneath our perch on the canyon wall, he could very well be setting his own funeral pyre. He found another small part of the gorge wall where he could set the fire and control it.

And just as he got the fire going well, the faint sound of a helicopter drifted into the canyon. Amazing! It was almost like seeing a mirage because the swirling water all day sounded like copter blades. Gina jumped up and down, waving her arms. But the helicopter was a long way off, and after a few seconds, it disappeared behind a ridge. Brandon fed the fire as quickly as he could, then started waving a burning stick. Gina took off her jacket, picked up a branch onto which she had tied an orange fabric square from Donovan’s bag, and started waving wildly.

The helicopter appeared again, in the distance, and vanished again. Four times it did this. Then it was gone. Unbelievable.

It was getting dark. We faced the fact that we’d be spending a third night on the mountain. But at least we had a small mat to lie on. And we were right. It wasn’t as cold at this lower elevation, about 4,200 feet. Donovan’s poncho helped to block the wind.

We had been through a roller coaster of emotions. Stumbling onto the campsite, hoping for human contact, then realizing that person didn’t survive (and yet seemed to have all the right gear). Discovering we were trapped, then finding the matches. Seeing a helicopter, then having to spend another night. Alone. Helpless.

Lying awake in the dark, chewing her piece of Orbit, Gina asked, “What if they don’t come back?”

Brandon didn’t have an answer.

Going for Broke

As our fourth day on the mountain dawned, we felt horrible. We were now going on 72 hours without food, and we’d each lost about 5 percent of our body weight. Brandon struggled just to stand. Gina was in even worse condition, realizing she’d started her period. We’d found some toilet paper in Donovan’s backpack, and Gina used it to fashion a pad.

That was it. Brandon told Gina he’d made a decision: “I’m going to light this place on fire. I’m going to light the whole damn mountain on fire.”

“Do it,” she told him.

We had a talk before Brandon left to start the fire and get water. Gina was afraid of splitting up. But they knew it had to be done. Brandon left Gina on the perch and disappeared under the canopy. Then she stared at the sky, willing a helicopter to fly overhead. For an hour, she lay on the perch and thought about her life, sometimes talking to herself.

My apartment is clean, my statements are filed away. I’ve talked to Mom, my sisters, my best friend in the last couple of days. Okay. I guess it can happen. She pictured her own funeral. She envisioned her family at home, searching for answers. She talked to her loved ones in heaven, asking for guidance, and prayed all morning, asking for God’s help.

Meanwhile, beneath the tree cover, Brandon waited for the wind to shift, as it heated in the valley and swept back up the mountain, away from the perch. He found a fallen tree, stomped on it, and piled twigs and leaves into the indentation he’d made. Once he got the fire going, he knew it would spread quickly. Heading back to Gina, he could already hear the fire growing behind him, and by the time he got back to the perch, the flames where everywhere, gathering in the scrub oak, climbing up 40-foot cottonwoods. It was almost deafening.

“Was that you?” Gina said as he climbed up to her. The fire was suddenly everywhere, overwhelming. “Did you do that?”

“Obviously I did. Who the hell else is lighting fires around here?” And even then we were able to laugh—for just a moment.

We looked down at a half-acre blaze. The wind was blowing from our backs, carrying the flames and smoke away from us, up the mountain. But it was so hot that, even from this distance, we could feel it on our faces. Trees were exploding, and Brandon thought it was like the biggest string of firecrackers he’d ever lit.

“What are we going to do if it starts coming toward us?” Gina asked.

“I really hope search and rescue gets here before that happens.”

The sky was bright blue, perfectly cloudless, and thick black smoke poured out of the gorge. “How are you not seeing this?” we said probably 50 times. “How could you not see all that smoke? Come on! Come on, y’all!”

Slowly, the fire started to burn itself out after about 45 minutes. We watched as wood turned to white ash, and where once we only saw green foliage, now we could see the floor of the gorge. This was it. We’d shot our one flare, and it hadn’t worked. And then, a little more than an hour after Brandon had lit it, the fire was pretty well gone.

At that very instant, we heard a thumping. Coming up the canyon from behind us. We turned, and there was the sweetest sight we’d ever seen in our lives, flying around a bend, right at eye level: the helicopter.

We waved and jumped. Gina’s legs were so weak they crumbled beneath her.

From the sheriff’s helicopter boomed: “Brandon? Gina? Are you okay? Stay here.”

Brandon thought, Who else would we be? And where the hell are we gonna go?

From the helicopter boomed: “We’ll be back.” It spun and thundered down the valley.

Gina turned to Brandon and told him, “You saved my life.” She gave him a huge hug. We tried to cry, but we were so dehydrated that our bodies physically couldn’t make tears. Brandon just kept thinking, We made it. We made it. We made it.

And we both understood. It was John Donovan’s matches that had saved our lives. One life ended so that another life might be saved.

Epilogue

Once inside the helicopter, Gina tried to hug the pilot and kiss his cheek, overwhelmed by emotion and thankfulness. Steve Smith let her know that she was okay now and needed to sit down and put her seat belt on—Brandon still needed to get in. Flying out of Long Canyon, we saw that we’d only made it halfway down—and even if we had found a way down or around the 100-foot waterfall, there was much more below that. Brandon told the rescuers that we had found a campsite belonging to a John Donovan. Smith had flown search missions for Donovan a year ago and immediately radioed in the discovery of the bag and campsite.

Donovan was a bit of an eccentric who grew up an orphan. He didn’t have a phone and had once lived in an abandoned bank that didn’t have heat. He had been a social worker in Petersburg, Virginia, and had never married. His only family, really, were fellow hikers in the Old Dominion Appalachian Trail Club. He was a veteran hiker, spending 100 days a year on the trail, but he often got lost. His friends called him “El Burro” because of his slow, stubborn pace and “Sea Breeze” because of an old bottle of the astringent that he carried whiskey in when he was hiking. His friends all say he was a generous, kind man. Donovan had retired recently and was through-hiking the Pacific Coast Trail in 2005 when he became lost in a snow storm and was trapped in Long Canyon. A month after we were rescued, a team from the Riverside Mountain Rescue Unit returned to retrieve Donovan’s body, which surprisingly had not been burned. He was laid to rest, as he wished, at a VA cemetery in Amelia, Virginia.

Patrick McCurdy, one of the Riverside rescue volunteers who went back in for Donovan, says he initially thought we were pretty stupid to have gotten lost the way we did. But McCurdy had never been down into Long Valley. Once he had, using a machete to hack through the underbrush, seeing how steep the canyon walls were, he understood. To his mind, there’s no question we would have died if it weren’t for that half-acre signal fire. “No way,” McCurdy says. “We never would have sent people down into that gorge.”

Today, we’re still together. Brandon, in fact, made a trip up to Iowa to meet Gina’s family in late October. (He passed the test.) People ask us when we’re going to get married. Some have told us, “After something like that, you’re either never speaking to each other again or you’ll spend the rest of your lives together.” But we’re in no rush. We’re young, and, after all, we’ve only known each other a few months. Besides, this dating thing can be an adventure.

| Leave your comment | ||||||||||||

| Choose an identity | ||||||||||||

| Blogger Other Anonymous | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||