|

| GAMMING IT UP: Mark Reeves, a race fan from Wichita Falls, needs a veterinarian. Because his pythons are sick. |

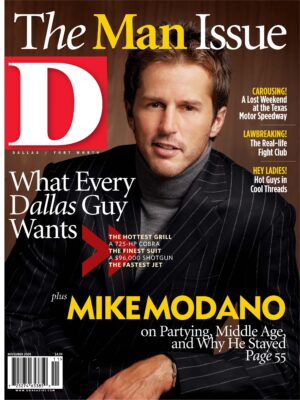

First, I’d like to thank my sponsors. Without the generous support of Hall Motorhome Rental, the Texas Motor Speedway, and D Magazine, none of this would have been possible.

Second, there are certain details about my maiden NASCAR weekend that I will not share. You’ll just have to trust me on this. It’s better for everyone involved.

This happened back in April, at the prolix Samsung/RadioShack 500. As I said, it was my first NASCAR experience. That’s how I pitched it to my sponsors: let me venture out to The Great American Speedway!™ and see with virgin eyes what this business is all about. Two hundred and eleven thousand people! For a single sporting event! Can you imagine? The Speedway becomes the 11th-largest city in the state (bigger than Lubbock but smaller than Garland by 4,768 souls, according to the 2000 census). And I didn’t want to go for just Sunday afternoon, the day of the main event. No sir. I wanted the full monty. The whole weekend. Because I’d heard stories about what goes down at night in the track’s infield campground, stories about wanton NASCAR women, stories about parties where suggestive dancing was not only tolerated but encouraged, stories, in short, about redneck profligacy on a scale seldom seen since Biblical times. It all needed to be documented.

Also, this is the first year the Speedway will play host to not just one but two big Nextel Cup races. In the journalism game, this is known as a “hook.” I said I needed an expense account, five press passes, and an enormous recreational vehicle. I promised to have a report ready in time for the more succinct Dickies 500, on November 6.

What follows is that report, sanitized a bit so that it won’t make your eyeballs rot.

|

| ROUGHING IT: Fifty thousand people fill the infield of the Texas Motor Speedway. Not many are teetotalers. |

GET ON THE BUS

Our expeditionary force consists of four brave, hearty souls (a fifth, a photographer and member of the fairer sex, will rendezvous with us at the track). We are:

Eric. Age: 38. Marital status: married. Children: one daughter, age 10. Occupation: editor of in-flight magazine. Sobriquet acquired during NASCAR weekend that is suitable for mention in family publication: Fruit Pie (on account of he purchased a fruit pie at 7-Eleven, before we even picked up the enormous RV).

Joe. Age: 35. Marital status: never. Children: one boy, age 9. Occupation: physician’s assistant to a dermatologist. Sobriquet acquired during NASCAR weekend that is suitable for mention in family publication: Swamp Toe (due to liquefied toenail on big toe as result of earlier soccer injury).

Adam. Age: 32. Marital status: married. Children: none. Occupation: senior editor at city magazine. Sobriquet: strangely, Adam would be the only member of the group to avoid a nickname; even the photographer, Allison, would be tagged with the name Picture Pants.

Me. Age: 35. Marital status: married, as of press time. Children: one boy, age 6; another on the way. Occupation: you’re looking at it. Sobriquet: God (origin a casualty of sanitization).

It is juvenile, I know. We are fathers and husbands. One of us even has a real job. And yet we’re giving each other nicknames. Wait, it gets worse.

|

| Front tire carrier Todd Draklulich feels the pressure. |

We take delivery of our enormous RV on Friday morning, at Hall Motorhome Rental, in Royse City, just past Fate. By agreeing to mention that Hall’s web site is www.hallmotorhomerental.com, I got favorable terms on the rental of a Diplomat I, a $150,000 house on wheels that, at the press of a button (and when safely parked), expands sideways like an accordion. Except this accordion is 40 feet long and features a kitchenette.

I get a tutorial on its operation from a Hall employee named Shane. Shane is a capable man with grime under his fingernails and a nametag that says “Shane.” He speaks quickly. “Here’s your inverter. Flip this switch if you want. But whatever you do, don’t touch this one. This button works the stabilizers.” On and on he goes. Gray water, black water, airbrakes, generators. It all sounds important. But I’ve never driven anything remotely as large as the Diplomat, and all I can think is, “When we die in a fiery crash on Highway 67, just minutes after leaving Hall’s parking lot, Shane will be able to tell the insurance adjuster that, yes, the renter was given the tutorial and issued all standard safety warnings. Shane will be covered.”

Then we’re off, barreling down the highway. Terror! We’re as wide as the lane and 40 feet long, for God’s sake! I can only stomach 50 mph. Big rigs blow past us, their backwash rocking the Diplomat. And we’re headed in the wrong direction.

“Where is Fate?” I shout at my associates. They are lounging on the sofa, laughing. “Don’t make me pull this thing over and come back there! We should be in Fate! I’m getting off the highway. Check my blind spot!”

They refuse to help. As commodious as the Diplomat is, I sense then that it will be a long weekend aboard the thing with these jackals.

I get the Diplomat turned around and headed in the right direction, and we make a scheduled stop at a Wal-Mart in Rockwall for provisions. I push a shopping cart through the food section as the jackals load it indiscriminately with whatever meat product crosses our path: six gi-normous T-bone steaks, six ready-made hamburger patties, six beef-n-cheddar sausages, six bratwursts—why six when there are four of us?—two family-size variety packs of lunch meat, one eight-count box of extra-large egg-n-sausage breakfast biscuits, and one package of bacon (center cut).

I pause to ask the obvious: “You think we should get something to go with all this meat?”

Fruit Pie says, “You mean, like, more meat?”

In the end, reason prevails. We add to the cart a comically large tub of potato salad. Oh, and four matching Day-Glo green tank top t-shirts, $3.99 each.

|

| HANGING AROUND: Kade Berry, 20 months, hopes his dad Kirby will do it again. |

After Wal-Mart comes a liquor store, where the scene repeats itself, only this time with malt beverages instead of meat. Five cases of beer, gallons of whiskey. Loading it all onto the Diplomat, it’s clear we’ve overdone it. Drinking everything onboard would not only be irresponsible, it would be impossible. But no one says anything. Because it would not go well for the guy who asks, “Do you think this is too much?”

There will not be such a thing as “too much” this NASCAR weekend. We are four men, fathers and husbands, too stubborn to tap the brakes, rolling downhill in a runaway house on wheels, on a trip governed by its own momentum. It is perfect.

GENTLEMEN, START YOUR ENGINES

We approach the track from the south, on Highway 114. It is an absolutely glorious afternoon, blue skies, 75 degrees, breezy. With stops and everything, I’ve now had enough time behind the wheel of the Diplomat to feel a little more comfortable. In the kitchenette, the jackals have already opened beers. Fruit Pie is delivering a world-class filibuster about a new NASCAR rule that limits the rear-gear ratio on the race cars.

“Last year, they was runnin’ taller gears, prolly about 4.0,” he says. “Now they’re keepin’ ’em at 3.80 and 3.89. It’s gonna ruin the sport.”

It’s an arcane point. He is passionate about it. But he’s also full of it. Just like the rest of us, Fruit Pie knows next to nothing about NASCAR racing. He’s reading an article from the Star-Telegram about the gear rule, affecting a drawl for his disquisition.

“Every single person I meet this weekend, I’m going to beat them down with hot sports opinions about the rear gear,” he says. “That’s going to be my thing.”

Then—blammo—the Texas Motor Speedway shoots up out of the prairie and fills the horizon. God, but it’s big. I can’t help but get excited. The jackals clamber up to the front and gawk at it.

Swamp Toe takes shotgun, produces our parking pass, and commences to flashing it at every cop and Speedway employee we pass. We enter a maze of parking lots, and I mow down orange traffic cones. I slide open my window and yell at parking lot attendants, “Sorry! I’m sorry!” Swamp Toe shows them our pass.

|

| BEASTS AND BEAUTY: When one woman stepped up to the Hooter Meter (above), the crowd grew quiet. Taylor Schultz, 13, and Summer Stallons, 13, got their Mardi Gras necklaces with their smiles alone (below left). |

At length, we find our assigned lot and our parking spot. Now: backing the Diplomat into the spot. This will be the test. Our fellow race fans have already arrived. Every other spot besides ours is occupied by a motorhome. Awnings have been extended, encampments established. I have only a couple feet of wiggle room. Even the jackals know this is serious business and disembark to shout directions.

You know what, though? As it turns out, I have a natural gift for piloting large recreational vehicles. I dock the Diplomat—perfect, dead center—in one try. I lay on the air horn. Cheers go up. We plug the Diplomat’s umbilical chords into the water and electricity outlets, and everything is peaches.

I’ll skip the part where I insist on deploying the stabilizers, against the advice of the jackals, and blow all the power in the Diplomat. Why is that important? What matters is that, after only a few short hours of our beer and meat going without refrigeration, I solve the problem. I call an acquaintance of mine who actually lives at the track, in a condo. I haven’t talked to him in more than a year.

“Jack!” I say when I get Jack on the phone. I can hear party sounds in the background. “What’s going on, man?”

“Nothin’. Whatchew doin’?” Jack is a good ol’ boy, made a ton of money in a line of business I don’t understand.

“I’m in Lot 2, looking up at your place. I’ve got a 40-foot motorhome down here that has no power, and I’ve got three buddies with me who are drunk and pissed. Mind if we drop by?”

He tells me they’re watching the IROC race in his condo and we should come up directly. He’ll meet us at the elevator.

Now think about that: people live at the Texas Motor Speedway. A 10-story building, the Lone Star Tower, with office space and 76 luxury condominiums, overlooks Turn 2 of the track. Its promotional literature bids you: “Imagine yourself watching exciting racing action out of your own living room.” Yes, imagine. On a Cup race weekend, your front yard fills with 211,000 screaming people and 43 cars thundering around at 190 mph, crashing into each other, crashing into walls, catching fire. A one-bedroom unit starts at about $325,000.

Now think about that: people live at the Texas Motor Speedway. A 10-story building, the Lone Star Tower, with office space and 76 luxury condominiums, overlooks Turn 2 of the track. Its promotional literature bids you: “Imagine yourself watching exciting racing action out of your own living room.” Yes, imagine. On a Cup race weekend, your front yard fills with 211,000 screaming people and 43 cars thundering around at 190 mph, crashing into each other, crashing into walls, catching fire. A one-bedroom unit starts at about $325,000.

Jack is one of the few people who actually live at Lone Star Tower year round. His neighbors mainly use their places during big race weekends. He wasn’t really even a NASCAR fan when he moved in. “I saw the magnitude of the place, and I was just impressed,” he says, escorting us from the elevator to his place.

We push through his front door. Inside, there are marble floors and a woman whose name sounds like “Llama.” Llama has NASCAR boobs and is married to Jack’s friend, whose name I don’t catch. They offer us beer, but we’ve come prepared, each of us with our own small cooler on a shoulder strap.

One entire wall of Jack’s living room is a 10-foot-tall cantilevered glass wall. Below us, IROC cars are hammering around the 1.5-mile track. Here’s what you need to know about IROC: “IROC” stands for “International Race of Champions.” The IROC Series is sponsored by Crown Royal, which reminds you to “Be a Champion. Drink Responsibly.™” It’s a racing appetizer. In IROC, you find some of the same drivers who race on Sundays, in NASCAR’s Nextel Cup Series. But you also find some guys who normally run in lesser organizations, such as something called the World of Outlaws. And IROC cars are all identical Trans Ams attended to by a universal pit crew, the idea being that if all the cars are the same, it accentuates the drivers’ skill. And whereas a Nextel Cup race at the Speedway involves 43 cars and 500 miles, IROC is 12 cars doing 100 miles. And only 70,000 fans show up to watch.

We hunker down with our beers and watch the race. I crack the windows, and the roar of the Trans Ams floods Jack’s living room. Cars go all over the place. They crash into each other, and we have a perfect view of it, live. Then we turn to watch the replay in slow motion on Jack’s big-screen television. As the caution flag comes out, Adam says, “This is going to take forever. They’re going to have to exchange insurance information and everything.” This gets a good laugh out of Llama. Fruit Pie decries the rear-gear rule, to little effect. Each of us makes the observation that “Rubbin’ is racin’” about a dozen times, apropos of nothing except our ironic appreciation of Days of Thunder, until it’s not funny, then funny again.

When we tire of racing, we use Jack’s binoculars to scan the infield crowd, pointing out items of interest to each other, like an encampment of race fans who rented not one but two spots so that they have open real estate next to their motorhome for pitching washers. You can tell these guys are serious about their washer-pitching, because Jack says there’s a five-year wait to get an infield space.

In the end, a Frenchman named Sebastien Bourdais wins the race. Kurt Busch might have won it. He was leading on mile 69, but his right front tire blew, and he slammed into the Turn 2 wall, right below us. The blowout was caused by the universal pit crew, which had accidentally put Busch’s front tires on the wrong sides of his Trans Am. Which just goes to show you: rubbin’ is racin’.

We take leave of Jack and his luxury condo. The walk from the track proper to our lot is a rather long one, even when your cooler has been emptied of its contents. The Texas Motor Speedway would begin selling beer in the grandstands in June, at an IndyCar race, but for now most of the place is dry, and fans are encouraged to bring their own beverages, even though the fans don’t really need much encouragement on that front. Everywhere people are carrying coolers or pulling coolers on wheels or, if they don’t have a cooler, simply toting cardboard 12-packs of beer.

We reach the Diplomat, and drinking continues unabated. Eventually, a motorhome tech arrives, and power is restored. Night falls. Burgers are cooked on a grill assembled by Adam in total darkness, with no tools, and at the expense of part of his thumb, which bleeds. Poker is played. Swamp Toe becomes so inebriated and obnoxious that I promise to punch him in the mouth if he doesn’t stop it. He does not stop it. I do not break my promise.

We reach the Diplomat, and drinking continues unabated. Eventually, a motorhome tech arrives, and power is restored. Night falls. Burgers are cooked on a grill assembled by Adam in total darkness, with no tools, and at the expense of part of his thumb, which bleeds. Poker is played. Swamp Toe becomes so inebriated and obnoxious that I promise to punch him in the mouth if he doesn’t stop it. He does not stop it. I do not break my promise.

This is the sort of behavior our wives and children don’t need to witness. Frankly, they shouldn’t even have to read about it. Did I mention that I’m wearing a stained Bud Light t-shirt emblazoned with the gay pride rainbow and a trucker gimme cap that says “Jesus is my homeboy”? I mean, we should have outgrown this strain of idiocy years ago. We are acting like boorish frat-house punks, and if someone were to videotape our antics and then force us to watch ourselves in the sober light of day, we’d be ashamed. Again, it is perfect.

Eventually, we determine that we’re sufficiently fortified to make a run at the infield, site of untold delights and debauchery. We load up our coolers and head for it. Except for Swamp Toe, who is no longer ambulatory.

THE BELLY OF THE BEAST

You know that scene in The Ten Commandments where Charlton Heston goes up Mount Sinai, and the Israelites melt down all their tennis bracelets to make the golden calf, and a 7,000-person orgy breaks out, with folks chugging Manischewitz, belly-dancing, and playing freeze tag? That’s what the infield of the Texas Motor Speedway is like at night. Except with lousier lighting. And fewer Jews.

You enter through one of three fluorescent-lit tunnels under Turns 1 and 2. A steady stream of people—again, each person traveling with a supply of beer, some on bicycles, others riding golf carts—pours through the tunnels, everyone whooping and yeehawing like kids who’ve just discovered how an echo works. Then you emerge into the infield. Its scale is simply impossible to process at first. In the turns, the track banks at 24 degrees. Above the track, bordering the front and back stretches, loom the illuminated grandstands, the only source of light besides the grill fires and whatnot coming from the hundreds of campsites. It is a disorienting bowl filled with darkness and strange noises and diesel fumes.

The fumes! There are no electrical hookups in the infield, so 1,000 diesel generators thrum in the background, powering televisions and stereos and air conditioners, belching exhaust into the air. Some of the roads that wind through the campsites like a small intestine aren’t paved, either, so dust mixes with the exhaust. Tonight there is no breeze. It all gets trapped in the bowl.

The three of us hold our breath and dive in.

The roads are crowded with folks cruising. Pickups with their tailgates down, eight people in the back, handing out Jell-O shots. On race day, the infield can accommodate 50,000 people. There’s no telling how many of us there are tonight, but it feels like 50,000. We keep to the edge of the road so as not to get run down.

Near Turn 2, we find a yellow school bus that drove all the way from Iowa. It has a superstructure on top for watching the exciting racing action. It has also been outfitted with a metal slide that looks like it was stolen from a 1970s-era playground. To ride the slide, you must be a) female and b) topless. As we’re taking it all in, one of the Iowans offers his hand and says, “Hi, they call me Gums.”

“Why do they call you Gums?” I ask.

“Because I got these big, crazy gums,” he says. And it’s true. Gums has an impressive set of gums.

We stick around long enough to watch two women in their 40s ride the slide to the accompaniment of Blood, Sweat & Tears’ “Vehicle.” Then I pay Gums $5 to use the Iowans’ Port-O-Potty, establishing a personal record for a sum paid to urinate.

Across the street and down the road a piece, there is what looks to be a catering tent set up in one of the camp spots. But inside people are playing an elaborate, four-person racing video game on an 8-foot screen. The cars are controlled by actual steering wheels and pedals. We assume it’s a promotional deal arranged by a video game concern, but, no, it appears to have been put together by a guy who is simply very serious about his video games.

And then we witness a scene that, for me at least, is the quiddity of the infield experience. A 50-year-old guy in a Tony Stewart No. 20 Home Depot t-shirt shouts, “We’ve got a Hooter Meter taker!” In his hands, he holds a sheet of poster board on which are painted the words “Hooter Meter” and in which pairs of circular holes have been cut. The holes at the top of the Hooter Meter are smaller and labeled “A.” The ones at the bottom are larger and labeled “D.”

A blonde in her mid-30s steps up to Tony Stewart. She’s attired in a green cowboy hat and sequined t-shirt that has crossed checkered flags below the word “NASCAR.” The shirt is tied in a knot at the small of her back, exposing her belly, which, in all honesty, shouldn’t be exposed. A crowd gathers around her, like ants swarming onto a piece of hard candy. Traffic stops. People in pickup beds stand up to get a better view. The blonde says something to Tony Stewart that I can’t print in this magazine and then makes as if she’s ready to submit to the Hooter Meter.

“Naw, naw, darlin’,” Tony Stewart says. “The Hooter Meter don’t work with your t-shirt on.”

Tony Stewart does have a point. Her shirt would surely increase the circumference of her hooters and throw off the measurement. The blonde considers her options. Cameras flash. The crowd grows uncomfortably quiet, as if a loud noise might frighten the hooters and send them scurrying into the underbrush. It’s creepy.

But then the blonde demurs. I am relieved when the crowd does not take vengeance on her.

By this point, we’ve had enough. And, besides, we’re out of beer. En route to the Diplomat, I somehow get separated from my “friends” and wind up hopelessly lost in Lot 2, where everyone is already asleep. I wander between motorhomes, every one of which looks identical to me at this hour, whatever hour it is. Thankfully, Fruit Pie rescues me. He jumps out from behind a Prevost, yells “Boo!” and scares me so profoundly that I feel like I’ve had my bell rung. I see stars.

THE SOUND OF THE APOCALYPSE

I wake up Saturday morning on the floor of the kitchenette, feeling not refreshed. Fruit Pie regales Swamp Toe with tales from the infield about Gums and the Hooter Meter and everything else Swamp Toe missed. Adam makes Bloody Marys. We wash them down with extra-large egg-n-sausage breakfast biscuits heated up in the microwave.

But as morning approaches noon, the jackals seem content to remain aboard the Diplomat and watch TV and drink more Bloody Marys and, essentially, loaf around. They do not have sponsors to answer to. With no small effort, I convince them that we must pack our coolers with beer and head back to the track. Racing! We’re here to see racing!

Saturday offers another preamble to the big Nextel Cup race. It is called the NASCAR Busch Series O’Reilly 300. Here’s what you need to know about Busch Series racing: it’s exactly like Nextel Cup Series racing. Kinda. The cars are the same. More or less. Ford, Chevy, Dodge. They run 358-cubic-inch Methuselah V-8 engines that produce top speeds around 200 mph (though Cup cars have a little more horsepower). And, more and more, the drivers are the same, especially on weekends when a Busch race precedes a Cup race on the same track. The drivers use the Busch race to get familiar with the track. On the Speedway, for instance, there are some nasty bumps in Turns 1 and 2. All tracks look flat on TV. They aren’t.

But so anyway, I impress upon the jackals that we need to see the spectacle from the track proper and not just from a luxury condo. We load our coolers with High Life and hump it the half mile to the track.

It is another beautiful day in Fort Worth, Texas. Blue skies, high 70s. Today’s race has brought more spectators than yesterday’s. Helicopters thump-thump everywhere, ferrying in the fortunate who will spectate from the 144 luxury suites. On the ground, it’s a different story.

The race gets underway just as we enter the infield. Two things become apparent: first, we need earplugs. As we learned the night before, the track is a big bowl, and just as it traps exhaust fumes, so it traps sound. The human ear is not designed to tolerate the sound of 43 unmufflered engines generating 32,000 horsepower. As the field of cars spreads out and around the track, the sound comes from everywhere all at once. It is the sound of the apocalypse. Literally, it is frightening. We buy spongy green earplugs.

The other thing that becomes apparent is that the infield is no place to watch the race. What are you going to do? Stand in place and spin counterclockwise to follow the action? No, you are not. Because I can tell you from experience that you will get dizzy and not enjoy yourself. Instead, you watch only a 15-degree sliver of the track, and the cars rush by in an indistinguishable blur. No good.

Through another tunnel and up into the grandstands we go, to the rim of the bowl. There we find a spot under the overhang of the luxury boxes, in the shade. Adam brought electronic pocket Boggle, which, if you’ve never played, is a word-search game. We drink beer and watch exciting racing action and play pocket Boggle. But even with the earplugs, it is still so loud that I can’t spell. Beating Adam at pocket Boggle is difficult under ideal circumstances. Here it is impossible.

A few rows in front of us, I espy a woman whom I determine to be the quintessence of The Race Fan. She is wearing two fanny packs, Oakley sunglasses, acid-washed jeans, a ring on every finger except her left thumb, and a t-shirt that reads “I’m not a BITCH. I’m just giftedly bespoken.” She has three visible tattoos. Plus, she has a sign. It says “Boogity, Boogity, Boogity. We love you Darrell Waltrip. Let’s go racin’.”

What I understand about this sign: Waltrip is a FOX announcer who, at the green flag start to every race, says, “Boogity! Boogity! Boogity!” His meaningless catchphrase comes from the lyrics of the early ’60s hit “Who Put the Bomp (in the Bomp, Bomp, Bomp)?” by Barry Mann.

What I don’t understand about this sign: she appears to be showing it to the drivers. When caution flags come out, she stands up and points the sign at the cars, like she expects the drivers to be able to read it as they roar by at 100 mph, all the way down there on track.

After about 45 minutes of this—watching the cars go around in a circle, getting humiliated at pocket Boggle, scanning the crowd for good t-shirts (spotted: “Big Willie’s Taxidermy: Stuffing beavers for 30 years”)—it is time to leave. We’ve had enough.

|

| NIGHT LIGHT: At night, the immense, illuminated grandstands rob you of a natural horizon. The effect is enchanting. |

Listen. I understand a little something about racing. It’s not that I don’t get it. Because I think I do get it. I’ve read one of the best books ever written on the subject, Sunday Money, by Jeff MacGregor. NASCAR racing, as he wrote, “stands at a singular intersection of sports and theater.” It’s about “life-and-death stakes … the haunted history of the South and its cult of personality and our yearning for simplicity and our insatiable craving for celebrity and our ache for fable and our need to live vicariously in the glamour and accomplishment of others and our persistent American itch to create heroes.” I get it.

And I know something about what the drivers do. I once drove an actual Cup race car on the Texas Motor Speedway, in a driving school put on by an outfit called Team Texas. My car had a restrictor plate to keep it under 150 mph, and I only got to pass one car, on a straightaway. But after four laps, I was soaked with sweat and shaking from exhaustion. So I get it. What these drivers do is impossible.

And watching it in person is, without question, amazing. On TV, you can’t appreciate how fast the cars go, how loud they are. It stupefies and fascinates you. For 10 minutes.

But after 10 minutes, the racket takes it toll. You can’t play Boggle. You can’t talk to your friends. And when it gets down to it, you can’t really even watch the race. A lot of strategy goes into a 300-mile race. You can’t see any of it from the stands. Just cars turning left. And when they crash in Turn 4, you’ll be watching Turn 2, on the other end of the track. Suddenly 100,000 people will stand up and point and say, “Oooh!” By the time you look, it’s just burning tires, white smoke. Unlike at Jack’s condo, no replay.

Ten minutes. Then you can spend another 15 minutes people-watching. NASCAR offers unsurpassed people-watching. And then you can spend 15 minutes thinking about NASCAR, about how the Texas Motor Speedway is a temple built to the consumption of fossil fuel, from the faithful who burn unleaded to get there, to the generators that burn diesel down in the infield, to the race cars that waft 110-octane incense into the bleachers. In your mind’s eye, you can ride one of those helicopters up to 30,000 feet and peer down on the Speedway. From there, the 25,000 cars sitting in the parking lots surrounding the track and the cars chasing each other around it don’t look all that amazing. They just look small and silly. And you can wonder: when an archaeologist 5,000 years in the future digs up this temple, what’s he going to think about us?

And then you know it’s time to leave. Because that sort of besotted philosophical foofaraw is only going to spoil an otherwise pleasant day.

The jackals and I decamp and return to the Diplomat.

ENOUGH ALREADY

To say my first NASCAR experience is all downhill after Saturday’s Busch race would be disrespectful of my sponsors and not entirely accurate, but my first NASCAR experience is all downhill after Saturday’s Busch race.

By Saturday night, each of us has had enough of the other. We use Dos Equis and Maker’s Mark to calm our frayed nerves. We try to revisit the infield to distract ourselves, but the infield is closed to visitors on account of someone has apparently punched a cop.

Sunday morning dawns much like the day before, except I awake even less refreshed. The jackals want to pull anchor early and head for home. I ignore their wishes. We don our matching Day-Glo green tank tops, and Swamp Toe makes up a song to sing on our trek to the track: “Sterling Marlin (We Love You).” But our hearts aren’t in it. And when we get there, we can’t find seats. Our media passes only get us in; they don’t guarantee us a place to sit. As stated earlier, 211,000 people have shown up for Sunday’s big race. The Speedway’s official seating capacity is only 159,585. There is no room at the inn for four more butts.

Probably for the best. Sunday’s Cup race, by most accounts, is not as entertaining as Saturday’s Busch race. It suffers from what’s known as “yellow fever,” too many yellow caution flags. After 3 hours and 51 minutes of exciting racing action, Greg Biffle takes the checkered flag in the No. 16 National Guard/Post-It Ford. In Victory Lane, he shoots two Baretta .45 revolvers over his head. (I assume he uses blanks.)

We watch it all from the comfort of the Diplomat. We wanted to leave during the race, but several of our neighbors have parked their cars in front of their motorhomes, blocking our egress. At length, slowly, they return and move their cars for us. Finally, we can leave. Swamp Toe unhooks the water and electrical lines. I fire up the engine. But just as I’m about to release the airbrake, Swamp Toe climbs back aboard with the bad news.

“I was just talking to the guys next door,” he says. “He said the interior parking lots with the cars empty first, then the motorhomes get to leave. He said it’ll be another four hours.”

At this point, we’ve nearly run out of provisions. The pounds of meat, the cases of beer—all drunk and eaten. The only thing left is the comically large tub of potato salad and the bottle of Chivas. Too weakened by the weekend to complain, the jackals open both and settle in for the wait.

I stick to the potato salad. Because somebody’s got to drive.