Robert E. Lee Elementary, near the M Streets area of Dallas, is an old school. The plain, two-story stone building looks like it was built during the Depression, which it was. Lee was recently expanded, but the original 1931 building alone has more than 120 windows and 2,000 panes of glass on its exterior, give or take. About 450 kids attend the school.

Robert E. Lee Elementary, near the M Streets area of Dallas, is an old school. The plain, two-story stone building looks like it was built during the Depression, which it was. Lee was recently expanded, but the original 1931 building alone has more than 120 windows and 2,000 panes of glass on its exterior, give or take. About 450 kids attend the school.

Kids and glass and old buildings being what they are, sometimes those windows need replacing, and one day in February, that’s what brought Danny Mooneyham to Robert E. Lee. The burly 60-year-old is one of seven workers in the Dallas Independent School District’s glass shop. The men are called glazers. They work full-time to care for the hundreds of thousands of windows in the district’s 219 schools and other facilities.

Mooneyham has been a glazer for DISD for 17 years. He loves his job—and not just because it pays nearly $20 an hour and offers good security. Truth be told, he likes the kids. When they see him coming, with his cool wraparound sunglasses and tools, they gather around him. Especially the boys. They watch intently as he removes broken glass panes, then uses a chisel and hammer to bang out old, brittle window putty. Sometimes he uses a loud, electric grinder to get the stubborn stuff out. Mooneyham’s deep, gravely voice and tough-guy demeanor don’t scare the kids. He remembers one girl who ran up and patted his stomach, saying, “Hey, mister, you’ve got a big belly!” Even when he tells the kids to keep back, they close ranks on him, ask him questions, offer to help. Sometimes they scoop up the scraps, chunks of putty, and take them to the trash can.

That day in February, Mooneyham and his partner, Byron “Bubba” McMullen, who has worked as a DISD glazer for two and a half years, headed for the second floor at Lee to fix a broken window. It was a simple task. Remove the glass, chip out the old putty, put in a fresh pane, recaulk it. As they set up to start work, a contractor hired by the district to renovate the school happened by and asked a question that didn’t make sense to Mooneyham or McMullen. The contractor wanted to know if the men were licensed. Licensed? You don’t have to be licensed to repair windows.

That’s how it all started, with an innocent question from an outside contract worker. He told the two DISD workers something that made them question their bosses and eventually blow the whistle on them: the contractor said that the men needed to be licensed to knock out the putty because it was “hot.” It contained asbestos.

Neither Mooneyham nor McMullen had ever heard about asbestos in the putty. If it were true, if the putty were even 1 percent asbestos, knocking it out with a chisel while kids were around would be very much against the law. So they had the school’s principal write on their work order why they were leaving the job undone, and they returned to the shop. There they asked their supervisor, Jim Underwood, if the contractor knew what he was talking about. Did the putty contain asbestos?

“He acted like he didn’t know nothing about it,” Mooneyham says.

Underwood told them he’d look into the matter and get back to them. In the meantime, he told them to keep working. Which they did.

|

| THE WHISTLEBLOWER: Bubba McMullen had questions about the putty. When his bosses couldn’t answer them, he called the EPA. |

A week later, on a Wednesday, Underwood seemed to fulfill his promise. The district’s environmental and maintenance supervisors came to speak with the glazers about the window putty. The work crew, dressed in light blue knit polo shirts and jeans, huddled their small wooden school chairs around a table as their bosses—Underwood; Joe Williams, the coordinator for the district’s Emergency Response Team; Daryl Daniels, asbestos abatement field supervisor; and Stoney Crump, head of Environmental Services—tried to quell their fears. But the supervisors started the meeting by saying it had to be short, because they had somewhere else to be. And they didn’t offer much in the way of solid information.

“Stoney Crump told us that the EPA considered it a gray area, that it wouldn’t hurt us,” McMullen says. “He said, ’You can go downtown and stand on a corner and breathe as much asbestos from the brake dust.’”

It was McMullen—insistent but soft-spoken—who asked the most questions. Was the putty at Lee Elementary hot? Were there other schools that were hot? If they breathed the stuff, would they get sick? The supervisors didn’t have answers, and they grew more impatient with each question. Finally, Crump and the other supervisors said they would come back to the glass shop on Friday with more information. McMullen asked what the glazers should do in the meantime.

“Joe Williams told us to go ahead and chip the putty,” McMullen says. “He said, ’I’m your boss, and if you need someone to tell you to chip the putty, then chip the putty.’ He said we could sue anybody we want to because he’s retiring in a few months anyhow.”

The next day, McMullen and other glazers were sent to South Oak Cliff High School to replace some 30 windows, a large job. Protected by little more than gloves and safety glasses, the crew did as they were told. They broke out the putty with hammers and screwdrivers. Where it stuck, they used grinders, turning the old putty into a fine powder that drifted through the air. In one of the classrooms, while the men worked, students were there, trying to pay attention to their lessons.

And while he worked, McMullen couldn’t stop thinking about the meeting with his bosses and how they never really answered his questions. So that day, he called the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to ask how old putty should be handled and what this so-called “gray area” was that Crump had mentioned. He wanted to be ready for the meeting on Friday, when the supervisors said they would come back with answers about how to proceed. But he never got the chance. The meeting was canceled with no explanation. That Friday morning, McMullen, Mooneyham, and the others simply received their work orders.

And the following week, the crew was sent out to repair some 60 auditorium windows at W.H. Atwell Middle School. Another big job. And still there was no word from supervisors about rescheduling the meeting. So the workers in DISD’s glass shop started doing their own research on asbestos and sharing it with each other.

And the following week, the crew was sent out to repair some 60 auditorium windows at W.H. Atwell Middle School. Another big job. And still there was no word from supervisors about rescheduling the meeting. So the workers in DISD’s glass shop started doing their own research on asbestos and sharing it with each other.

Today, sitting at a picnic table outside the Samuell Grand Recreation Center, Mooneyham and McMullen talk about their self-guided asbestos education. A chill October wind blows leaves at their feet. Mooneyham chews nervously on a toothpick.

“I never had no inkling that putty had asbestos in it,” Mooneyham says. “Nobody ever said anything about it. I never thought it could get in lungs and not get out. I thought the body would get rid of it. If they’d a told me the stuff I was messing with has asbestos in it, I would have told them, ’No sir! I don’t want the job.’”

But more than his years of breathing pulverized putty, Mooneyham says there’s one thing he can’t get over: the children who may have been exposed to asbestos because of him. “What bothers me more than anything is I done this around little kids, 4- and 5-year-olds,” he says. “They’re eating lunch, and here I am chipping it out, and it’s settling on their food.”

Both men say they are worried about losing their jobs for talking with D Magazine. But there’s more at stake than their livelihood. There’s the well-being of the district’s 160,000 students and 20,000 employees.

“Asbestosis, it’s like getting AIDS, only it takes a lot longer,” McMullen says. “But you know the outcome. You know eventually it’s gonna kill you.”

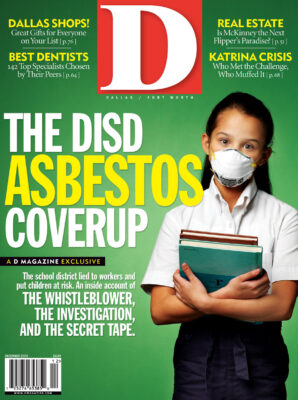

The guilt outweighed the fear of district retaliation for blowing the whistle. Just two months after first calling the EPA, McMullen agreed to help with an investigation into whether DISD knowingly broke the law by sending unlicensed workers to remediate asbestos-filled putty, sometimes with children present. Investigators found twice the allowed “safe” levels of asbestos. And McMullen wore a wire and went to the office of the district’s head of Environmental Services, Stoney Crump, to confront him. What Crump said in that taped conversation is troubling. But more troubling is the distinct possibility that the district will emerge from the investigation unscathed and unrepentant, its students, parents, and teachers left in the dark about all that dust around them.

THE MAGIC, FLAME-RETARDANT BUILDING MATERIAL

The word is Greek, meaning “inextinguishable.” Asbestos describes a group of metamorphic minerals that have been mined for thousands of years. Historically, asbestos was used in lamp wicks. The ancient Egyptians used asbestos in burial cloths. Legend has it that Charlemagne had a magic tablecloth interwoven with asbestos fibers. To clean it, he threw the tablecloth into a fire, where the crumbs were burned but the cloth wasn’t.

Asbestos is not dangerous when it is bound with other materials and left undisturbed. But when it is crumbled, pulverized, or in some way disturbed so that it becomes airborne, the microscopic fibers—1,200 times thinner than a strand of hair—can hang in the air for days. When inhaled, the fibers can lead to lung cancer, asbestosis, and mesothelioma. With asbestosis, fibers become trapped in the lung tissue, which leads to severe scarring as the body sends acid to try to break down the fibers. The result is a persistent and worsening cough with sputum, chronic shortness of breath, and lung or heart failure. Mesothelioma is a cancer that attacks the outer lining of the lungs and chest cavity, as well as the abdominal wall. Tumors grow in the membranes around the chest and stomach and spread to other organs, filling the chest with fluid, making it painful to breathe. Most people die within a year of diagnosis. In the United States alone, one estimate puts the annual number of asbestos-related deaths at 10,000.

Asbestos is not dangerous when it is bound with other materials and left undisturbed. But when it is crumbled, pulverized, or in some way disturbed so that it becomes airborne, the microscopic fibers—1,200 times thinner than a strand of hair—can hang in the air for days. When inhaled, the fibers can lead to lung cancer, asbestosis, and mesothelioma. With asbestosis, fibers become trapped in the lung tissue, which leads to severe scarring as the body sends acid to try to break down the fibers. The result is a persistent and worsening cough with sputum, chronic shortness of breath, and lung or heart failure. Mesothelioma is a cancer that attacks the outer lining of the lungs and chest cavity, as well as the abdominal wall. Tumors grow in the membranes around the chest and stomach and spread to other organs, filling the chest with fluid, making it painful to breathe. Most people die within a year of diagnosis. In the United States alone, one estimate puts the annual number of asbestos-related deaths at 10,000.

Of the different types of asbestos, chrysotile, also called “white asbestos,” was the most commonly used in building materials in the United States, owing to its abundance and malleable fibers. More than 90 percent of all asbestos found in buildings is white asbestos.

Through the EPA, the federal government began to regulate the use of asbestos in 1973, not long after medical science proved a direct relationship between asbestos exposure and lung disease (though as early as 1898 the Chief Inspector of Factories of the United Kingdom told Parliament in his annual report about the “evil effects of asbestos dust”). The EPA included asbestos in its list of toxic air pollutants called the National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP).

It didn’t take long for concerned parents and educators to realize that schools everywhere were positively filled from floor to ceiling with asbestos. In 1986, Congress passed the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA). The goal of the act was to minimize students’ risk of asbestos exposure by requiring districts and contractors to do the following: test the school for asbestos-containing material and maintain an asbestos management plan that shows where the material is in each school and how its dangers are to be controlled; make sure all schools have a copy of the plan specific to the individual campus; require reinspection of campuses every three years; and, significantly, notify parents and teachers each year about the school’s asbestos management plan and any abatement actions taken or planned on campus.

At first blush, McMullen says, a little putty from one window might not seem like a big deal, nothing worth notifying parents and teachers about. But then you do the math.

DISD, with its 217 schools, is the 12th-largest school district in the nation, with about 120 of its schools constructed before 1960, when builders were packing asbestos into just about everything—sheetrock taping, roofing tars, shingles, plasters, ceiling tiles. And, yes, window putty.

An average window that runs 17 by 30 inches might be held in place by up to a half pound of putty. A team of glazers might replace an average of 15 windows a day, which means 1,950 pounds of window putty per year. And the glass shop has seven full-time glazers.

When they hammer and grind the putty out, the powder blows in and out of the unsealed rooms, settling everywhere. “I’ve seen dust so thick before that you could write your name on a desk or the floor,” Mooneyham says. “It’ll blow up your nose and get in your mouth, in your shirt. I find it in my pockets.” Workers trudge through it, carrying it through the room and into the halls.

Another glazer, who didn’t want his name used, says, “After work, I’ll strip down, and putty will fall out of my underwear, along with some glass.”

Mooneyham says the district wasn’t providing him or McMullen with a respirator or protective clothing. They got a broom, a dustpan, and a 5-gallon bucket for cleanup. They swept it up and put it in dumpsters on campus or in the little trash cans in the classrooms.

McMullen calls himself a “country boy” and hasn’t yet seen a doctor to learn if he’s been exposed to asbestos. The substance shows up in mucous, urine, or fecal samples, although it can take years before the onset of any illness. McMullen says he’s been too tired, too busy to take the time away from work to see a doctor.

“Sure I’m worried,” he says slowly. “I’m fixin’ to be a grandfather. I want to take my grandbaby fishing. I don’t want to be sick.” And he says he doesn’t want to end up like his friend Fred Korn.

Korn is 72 years old and worked as a glazer for the district for 18 years. He has a wheezy, wet voice. His breathing is heavy, labored. He had to retire. Doctor’s orders.

He recalls scraping putty from outside the buildings, while the children were inside. “When they come up with the smoking ordinance, you couldn’t smoke because the wind would blow it in there,” Korn says. “If smoke could get in, I guess anything else could, too.”

About a year before retiring, Korn noticed he was struggling to catch his breath when he exerted himself. Sometimes he’d feel lightheaded. He chalked it up to his age. Gradually, though, it worsened until it became hard for him to do the simple stuff, like swinging a hammer or just walking. One day, he couldn’t even make it to his truck. He lost his breath and had to stop every few steps. And at night he would be jolted awake, feeling a hot, smothering sensation.

“I woke up and had to stand under the air conditioner to get cool air in me,” he says.

He was hospitalized at Medical City in Mesquite for a week. His doctor, Pedro Zevallos, diagnosed him with asbestosis in addition to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a progressive lung disease that the American Lung Association says is caused by long-term exposure to toxic substances. Korn did smoke, but he says he quit almost a decade ago.

“I sleep with oxygen, with a tube in my nose,” Korn says. “I worked as a glazer all my life. We’ve seen [training] films on asbestos, but DISD never showed us a film of it being in the putty.”

BLOWING THE WHISTLE

When Byron McMullen called the EPA that day in February after replacing dozens of windows at South Oak Cliff High School, he’d generated enough putty dust that it looked like he’d been rolled in flour. He just wanted to know: if asbestos was in the putty, should he be scraping it?

According to EPA reports obtained by D through the Freedom of Information Act, that call to the Dallas office of the EPA’s Criminal Investigation Division led to a series of interviews with McMullen and others. The agency launched a probe into the school district’s management of asbestos. And it enlisted asbestos investigators with the Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS) to help determine whether and what regulations had been violated.

State asbestos investigator Frank Rodriguez would not speak to D, citing an ongoing case. But the notes in his report, obtained through the Open Records Act, tell a disturbing story. In mid-March, acting on a tip, he paid an unannounced visit to George W. Truett Elementary, in East Dallas. There he found McMullen and Mooneyham replacing a window in room number 118, a first-grade classroom. Rodriguez warned the workers that if the putty contained asbestos and they knew about it, they each could be fined up to $10,000. He collected samples from the room and from a bucket of old putty that the men said had come from another school. That afternoon, Rodriguez called Stoney Crump, in Environmental Services, a man who presumably would know a great deal about hazardous materials on campuses.

“I asked Mr. Crump if the asbestos management plan identified window glaze. Mr. Crump replied he did not know … ,” Rodriguez noted in his report.

“I asked Mr. Crump if the asbestos management plan identified window glaze. Mr. Crump replied he did not know … ,” Rodriguez noted in his report.

Crump said that he would find out and fax the information to Rodriguez, along with proof that glazers had met their mandatory two-hour asbestos training. However, despite repeated requests, Crump never turned over the information. Not even after Rodriguez called a week later and told him that both putty samples had been tested and were found to contain 2 percent white asbestos.

For an environmental supervisor, that number—especially given that it described samples taken from a classroom where children are present—should have pricked up his ears. Any material with an asbestos content greater than 1 percent is considered hazardous under state and federal laws. The EPA promptly forwarded the samples to their Denver lab for further testing.

But Truett was the first of three schools that Rodriguez discovered had hazardous window putty. He later found that hot putty had also been chipped at Clara Oliver Elementary, in South Dallas, and Bryan Adams High School, in East Dallas. And, furthermore, Rodriguez found evidence that suggests the district lied to its glazers about the hot putty at Bryan Adams.

At Bryan Adams, glazers were told to replace the windows in classrooms 203, 123A, and 124. When Rodriguez walked through room 203, kids were in class, and workers had left behind a mess of putty dust and scrapings that were all over the tabletops and floor. In the next classroom he visited, Room 124, workers were chipping out putty and replacing windows with students still in the room. In his report, Rodriguez again noted that putty dust coated the windowsills, desks, and floor. Glazers produced an e-mail that they’d been given by their supervisors.

The e-mail had come from the lab used by the district to test for asbestos. One room at Bryan Adams, according to the lab, was in fact clean. But that room number on the e-mail had been crossed out, and someone had instead written in 123A and 124, where the work needed to be done. Rodriguez gathered samples from room 124. (Work had not yet begun in room 123A.) They came back hot.

Strangely, though, during the five-month state and federal joint investigation, as Rodriguez found hot sample after hot sample, the district started doing its own asbestos testing—and it found nothing. How to explain why DISD’s samples would be clean, if the state found “hot” putty?

Todd Wingler, an environmental engineer and spokesman for the department of health in Austin, says results will vary at a particular building depending on its age. If the sample was taken from a new wing, or a newer window, or if an old window had already been caulked over with a nontoxic silicone-based putty, then the samples would come back clean.

“Do we know Rodriguez tested the same windows that Stoney tested?” asks Daryl Daniels, the district’s field asbestos abatement supervisor.

“We never saw their results,” Crump says of the state. “We sampled the windows that were broken and on the work order. That was our procedure. If an inspector shows up, he could be getting samples from other windows.”

Essentially, Stoney Crump’s claim is that the district sent glazers to clean rooms, and the state investigator must have tested different, hot rooms. This theory, though, doesn’t explain what we know happened at Truett. Unless Rodriguez lied on his report, he tested the putty from the same room where the men were working—not to mention the putty in their bucket, which the men had scraped from another school.

DISD officials also deny that dust was left on the floors and desks, as depicted in photos taken by Rodriguez. They maintain that Rodriguez could have been in any room and, by implication, could have photographed anything. Again, though, unless Rodriguez is incompetent or dishonest, the district’s claim defies reason.

For his part, Rodriguez took issue with the district’s findings. He was quick to note in an interview with EPA agents that there was a “white, silicone material on top of the gray, caulk-type compound,” and he “suspected DISD may have only sampled the top, white layer and not the bottom, gray layer.”

When McMullen learned that the state’s tests showed that the putty at Truett contained asbestos, he was done giving the school district the benefit of the doubt. He was tired of waiting for answers. He had tried to go through the chain of command to get information.

“I feel they lied to me,” McMullen says. “They were gonna sweep it under the carpet. If the state hadn’t come out, we’d still be chipping putty.”

That’s when he agreed to wear a wire and pay a visit to Stoney Crump.

|

| MESSING WITH THE COUGAR: At Bryan Adams, someone doctored the work order, sending workers into a “hot” room. |

THE TAPED CONVERSATION THAT NEVER HAPPENED

On the morning of Monday, April 4, Bubba McMullen couldn’t choke down breakfast. He was nervous and his palms were damp. At half past 6, he put on a recording device for the EPA and drove to his supervisor’s office off Lamar Street, in the old Sears building. He kept wondering if he was doing the right thing. He parked the van, took a deep breath to clear his mind, and went in to see his boss.

After a couple of minutes of waiting, Stoney Crump came out to greet McMullen. Crump said he was “running hard already this morning” and had a staff meeting to attend shortly. He ushered McMullen into his office. It is a small, cluttered space with diplomas on the wall and piles of paperwork and books on the desk and floor. McMullen took a seat in front of the desk but Crump stood. He was restless, fidgety.

A transcript of the tape has McMullen asking simple, direct questions to which Crump provides stammering, incomplete, and sometimes contradictory answers. Then he places blame on others.

McMullen: “I was one of the ones out there at Truett when [the asbestos investigator] came in there on us … so I was just wondering if you’d heard anything about [it] ’cause I got a bunch of windows knocked out at Truett.”

Crump: “We have to schedule a cleanup over there. What we did was took some samples, but the bond program [passed in 2002] had already taken samples … but they didn’t make us privy to their analysis. That’s the problem I’ve had with the bond program.”

McMullen tells Crump he was threatened with a $10,000 fine and has been told that Truett’s putty was hot.

Crump says that he provided the state with sampling that shows Truett is clean. But later in the conversation, he says he’s aware of a previous report indicating that samples contained asbestos.

Crump: “Well, some of the material at Truett was hot … and it was identified in the previous report, so I wish Mr. Underwood [the glass shop supervisor] would let us know about that school … .”

He speculates that environmental consultants for the district don’t know about asbestos in the putty, even though putty is listed on the EPA’s web site as a possible source, and he says the matter falls outside his department’s scope.

Crump: “I would bet one out of five, maybe one out of seven even, would not consider window caulking a sample material … . It’s just not in the list of materials to sample from the state. … But this thing is so much of a gray area. It does not fit into our daily operation of asbestos abatement, or even disturbance of a material that may cause friability.”

McMullen asks if he should see a doctor. Crump says he has nothing to worry about.

Crump: “They’re not gonna be able to tell you anything. You’re gonna breathe a thousand fibers today driving around in the pickup … know what I’m saying? That’s why I’m trying to explain a little more about [it] ’cause I know you guys don’t know about asbestos.”

McMullen: “I don’t have a clue.”

Crump: “But I’m telling you, if from everything, all the training I’ve had, all the medical stuff—and you can get all kinds of stuff on the Internet—exposure to asbestos … in order for it to scar your lungs, or to be damaging to you, it’s gonna be treated as a foreign body anytime you breathe it into your body, just like dust … fiberglass, anything like that. Your body will do a real good job of, you know, getting rid of it … .”

He goes on to tell McMullen that not only will it not hurt him, but he’ll probably die of old age before complications from asbestos.

Crump: “You hear about these people working in grain elevators … and there were grain in their lungs or something, and, I mean, they don’t even know that they had it there until they die, someday, and it’s old age usually. But it doesn’t affect them, and it’s not actually the killer of them, you know, so it stays in their body. But our bodies just function … with it in there. We drink asbestos. It’s in our water, you know.”

Crump, most shockingly, then tells McMullen he’s not at risk of exposure to asbestos because only a small percentage of the putty is toxic.

Crump: “[What] you’re finding in this window caulk is 1.5 percent and 2 percent [chrysotile asbestos]. And we’ve gotten a couple samples go as high as 10 percent. But let’s say 10 percent in a sample of material … 10 percent of it is asbestos—so then what is the chance while you’re scraping that, that actual 10 percent … becomes airborne and you breath it?”

McMullen: “So you don’t think I should have to go get checked or nothing?”

And once more, despite the fact that asbestos exposure can be readily determined through urine or fecal samples, Crump insists that a doctor would only perform an x-ray, and nothing would show up. Then Crump slips for the second time and seems to indicate that he knew about asbestos before the incident at George Truett Elementary.

Crump: “I’m just saying, from a health standpoint, I mean, if I was a glazer and I know what I know now, if I was in your position [and] I’d been doing the same thing every day, without, you know—but we’re going up and beyond this from now, which should have been done by the district a couple years ago—not a couple years ago, [but] since day one, since we knew about asbestos.”

Crump tells McMullen that he’s not worried about the state asbestos investigator’s threats. He’s talking about Rodriguez.

Crump: “He doesn’t intimidate me. What he can do and what probably will happen out of this, the district will probably get a fine, we’ll get a violation … .”

The conversation ends with Crump saying the district never knew about asbestos in the window putty but now that it does, the putty will be handled properly.

When it was over, McMullen walked back to his van. He shut off the recorder. He turned to Mooneyham, who had waited a half hour in the van for him, and shook his head.

“I felt he’d filled me full of bull again,” McMullen says. “He never did answer my questions. He never looked me dead in the eye.”

Today, when asked about the conversation, Crump denies ever telling McMullen that there was a “gray area” where the EPA was concerned. In fact, Crump denies ever having the conversation. It simply never happened.

DEATH BY BUREAUCRACY

Based on his inspections, Rodriguez, working for the state, recommended that glazers should have received asbestos worker training, that they should have a physical and a respirator “fit test,” and that they should be licensed in the state as abatement workers. Rodriguez concluded that DISD was out of compliance with the Texas Asbestos Health Protection Act as well as the federal Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act. He recommended the state take enforcement action against the school district.

And if it were up to the state, that’s probably what would have happened. But remember that Bubba McMullen’s first call was to the federal EPA. They were the ones who brought the state into the investigation. And while the state was testing putty samples, so were the feds. The problem: they were using two different tests.

When looking though a microscope at a material sample, a lab technician can either estimate the percentage of asbestos—or actually count the fibers, one by one. Not surprisingly, “point counting” is more time consuming and more expensive. That’s the method that federal law demands be used in order to press criminal charges.

While OSHA has deemed any exposure to asbestos harmful, the government has grounds for prosecution only if the material is at 1 percent or higher. The results of the EPA’s point-counting tests showed that the putty samples from DISD contained just under 1 percent asbestos. The EPA closed its investigation.

And that leaves the state in an awkward position. The federal government brought the state into the investigation but then threw out the state’s test results and declared the matter finished.

“As long as I’ve been doing this, we have been prosecuting without point counting,” says Todd Wingler, the environmental engineer with the state department of health. The state has always used the estimation technique of determining asbestos content. Jennifer Jaber, director of Dallas-based Quest MicroAnalytics, a lab used by state and federal agencies, says the estimation technique is valid. She says that even for a new analyst, one in training, the lab results are 90 percent accurate. “For someone experienced, it’s 100 percent,” she says confidently.

As of press time, the state department of health services has not decided if it will move forward on a case against the district.

But how hot the putty was seems beside the point. The point is the putty did have asbestos in it. The best-case scenario is that it contained less than 1 percent asbestos, and the district was simply inept in handling it. But the worst-case scenario is that the putty contained 10 percent asbestos—a figure mentioned by Crump—and it deliberately and systematically endangered the health of children and workers, then lied about it and covered up what it was doing.

To this day, it’s impossible to get a straight answer out of the district or a clear timeline that shows what it knew and when. In a phone interview in October, DISD environmental supervisors said they first learned in January or February that asbestos was in the window putty. That was when the contractor led Mooneyham and McMullen to start asking questions. According to the district, schools are regularly inspected to make sure areas with known asbestos-containing materials have not been disturbed. However, window putty had not been identified and so was not part of reinspections. Crump said he “didn’t feel that it was well-known in the industry” that asbestos was in window putty. But, again, window putty is specifically listed on the EPA web site as a potentially hazardous material.

And the February timeline doesn’t jibe with what we know about the district’s bond program, which was passed in 2002. At that time, before any remodeling was done, the district had environmental consultants collect new samples, and it discovered that window putty contained asbestos. Crump himself told McMullen that in the taped conversation. When the EPA asked Crump about those tests done in 2002, he claimed the important information essentially had gotten lost in the shuffle.

The EPA’s David Eppler received that first phone call from Bubba McMullen. Eppler called Crump on March 7 to ask about the district’s asbestos abatement program and wrote in his notes that Crump told him he had been informed of the problem and had called a meeting February 23. “[Crump] had assumed that a proper plan was in place for handling asbestos-containing materials. In the meeting, he discovered that a plan had existed some years ago, but because of staff changes and time, the plan had been forgotten, and proper procedures were not being used. Crump had called OSHA and the Texas Department of State Health Services … to find out exactly what procedures should be put into place. EPA was the next agency he was going to contact, so my call to [him] was timely.”

So on March 7, Crump presumably had on his “to do” list: “Call EPA, find out how to deal with asbestos-filled putty.” But on April 4, while McMullen was wearing a wire, Crump said the glazers weren’t in any danger—10 percent is such a small number, we all drink the stuff anyway—and they should go on with their work.

Today, Crump says the district took “proactive” measures on April 19 to ensure school and worker safety. That’s the day, he says, the district began treating all putty as if it contains asbestos. If a window needs to be fixed, the room is sealed and asbestos abatement methods are used. Glazers were also told to watch an asbestos training video.

None of it makes sense. And none of it explains the suspicious work orders for Bryan Adams High School. “We asked Jim Underwood,” Crump says. “He couldn’t give us an answer.” DISD spokesman Donny Claxton says the district is still inquiring about the e-mail with the altered room numbers.

Because of a purported breakdown in communication, who knows how many children were exposed to asbestos or what the long-term consequences may be for their health, not to mention what might happen to those DISD employees who breathed the putty dust day in and day out? For an institution whose business is the well-being of children, it is remarkable that district officials to date have made no effort to notify parents whose children may have inhaled asbestos—not just at Robert E. Lee, George W. Truett, Clara Oliver, and Bryan Adams, but at all the schools where putty was pulverized over the years.

Sitting on that picnic bench outside the Samuell Grand Recreation Center, McMullen rubs his mustache and looks small, defeated. He sits hunched over the table. “I feel like it was all for nothing,” he says of helping with the investigation. “But that stuff is still harmful. I don’t want to lose my job.”

“Down there they don’t care about you,” Mooneyham says. “You’re just a body. A piece of meat.”

J.D. Sparks is the managing editor of Park Cities People.