ON THE MORNING of January 22, more than 800 employees of the Dallas Morning News

filed into a hotel ballroom to hear the publisher’s annual

state-of-the-newspaper speech. Jim Moroney strode to the podium, a

gangly 47-year-old knot of energy in a powder-blue shirt and a

red-patterned tie. In years past, his presentation had been brief, his

goals modest. Not this time.

The News, he declared, was

like an outwardly healthy person with serious physical problems. “The

patient may appear healthy, but, frankly, he’s slowly dying.” In the

past three years, profitability had dropped 35 percent, he said. Home

delivery had declined 10 percent since 2000.

Moroney, who had

been publisher of the Belo Corp. newspaper for less than three years,

compared the paper to the American colonies and France in the 18th

century and Russia in the early 20th century. In each case, he said,

arrogant heads of state ignored the needs of those they governed. Those

societies needed radical changes, and so, now, did the News. “We need a revolution of our culture,” Moroney said.

To

accomplish this, the publisher insisted, the newspaper needed to shake

off ennui. Managers should stop stifling the staff’s criticism. Editors

should praise—not punish—dissenters. “Be thankful for the people who

speak up,” he said. “They are our best hope for getting it right.”

Moroney’s

“Fidel” speech lasted an hour and 20 minutes. In the final minute, he

used the word “revolution” seven times, and the crowd in the ballroom

gave him a standing ovation. Many were stunned by what they’d heard,

particularly Moroney’s praise for newsroom hell-raisers. “I thought he

was talking right at me,” says Pam Maples, a 14-year veteran of the

newspaper and a Pulitzer Prize winner. “When he was saying things like

that, I felt like I finally fit in.”

The publisher is proud of

his call to arms. Unlike his predecessor, he encouraged staffers to

speak on the record for this story.

Moroney has definite ideas

for the paper’s transformation. For one thing, he sees investigative

reporting as central to revitalizing the News. “Enterprise

reporting is essential to a great newspaper,” he says now. “The highest

calling of this profession is well-done investigative journalism.”

In the last decade, Brooks Egerton has been the most prolific investigative reporter at the News.

Moroney’s message excites him, but he wonders if the paper’s culture is

too entrenched. “In recent years, the Morning News has tended to hire

people—both as editors and reporters—whose orientation is not to rock

the boat,” Egerton says. “They have bred these rabbits to be docile.”

Whether the rabbits or the revolutionaries will win is an open question.

|

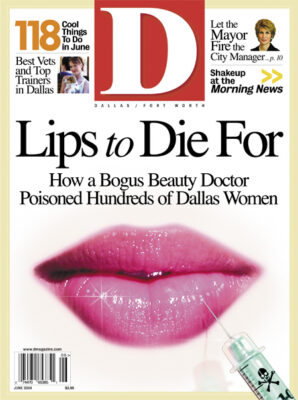

| POWER LUNCH: Moroney held a brown-bag meeting with reporters. Managers were barred. |

DAVID HANNERS CAN STILL recall his sense of excitement when he landed a job with the News in 1982. The paper was hiring young, hungry types like him and unleashing them. For decades, the News had displayed little appetite for enterprise journalism. But at the time Hanners got his job, it was battling the Dallas Times Herald for journalistic supremacy. One would win; the other would fold.

What occurred in that period demonstrates that great journalism is mostly a matter of will. Before 1986, the Dallas Morning News

had never won a Pulitzer. Between 1986 and 1994, it won six. George

Rodrigue and I won that first Pulitzer for a series we did on racial

discrimination in public housing. A series demonstrating that Texas

prosecutors routinely excluded blacks from juries was cited in the U.S.

Supreme Court’s 1986 ruling prohibiting that practice, and it earned a

grand prize from the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards. Four

reporters and a photographer who produced a special section about the

homeless in Dallas won the Newspaper Guild’s 1986 Heywood Broun award.

All this in a single year.

More awards rolled in. So did real-world results. The News

convinced the federal government to shut down taxpayer-funded slums and

kill plans to build new ones. It took on institutionalized violence

against women from Thailand to Texas. “The paper had an appetite for

red-meat journalism,” says Dan Malone, who teamed with fellow reporter

Lorraine Adams to produce a series of stories exposing police

misconduct that won a Pulitzer for investigative reporting in 1992.

But by then the atmosphere was already changing. This became clear when a sheriff sued the News

for libel over stories exposing drug dealing in South Texas. That led

to an internal showdown at the paper. At a November 1991 meeting, the

paper’s management demanded that their attorneys be allowed to reveal

confidential sources if, in pretrial depositions, they denied having

provided information. The reporters—Gayle Reaves, David McLemore, and

Hanners—refused. They said this would not only betray promises of

confidentiality, but also could endanger lives.

Jim Sheehan,

then the president of Belo, disagreed. According to Hanners, “Sheehan

told us, ’This company can protect sources, or it can protect

shareholders. Given that choice, you can rest assured this company will

always fall on the side of the shareholder.’” Sheehan, who retired in

1993, did not return several phone calls.

Months later, one of

the men who had been subpoenaed as a possible source was shot and

seriously wounded. In the end, the suit was settled out of court, and

the sources were not outed, but the reporters never forgot that

meeting. “Our bosses sat there like bumps on a log,” says Reaves, who

won one Pulitzer and was a finalist for another. “It was hard to have

respect.”

Bob Mong, the paper’s managing editor at the time of

the dispute, now its editor, acknowledges that he and other editors did

not defend the reporters during the meeting with Sheehan, but he says

they did so in other ways. “Could we have handled that situation

better? Yes,” he says. “Did we handle the situation behind the scenes?

Yes—and very well.” But Hanners, who had won a Pulitzer for explanatory

reporting in 1989, feels that the episode “marked the end of aggressive

investigative reporting at the Morning News. After that, they lost their stomach for the fight.”

The landscape also seemed to shift a month after the meeting with Sheehan, when the Dallas Times Herald

folded, leaving the News with a monopoly. It was after that, some staff

members say, that the paper’s culture turned against its hell-raisers.

“Your career didn’t always go where it should if you were too vocal,”

says Maples, projects editor since 2000. “The culture and the coverage

go hand in hand. If you breed a culture like that, then your coverage

gets softer.”

Reporters cite several casualties of the softer

era: stories involving American Airlines; Ross Perot’s run for

president; and a North Texas congressman (whom one editor referred to

as a “good friend” of the newspaper); coverage of tax and bond

elections in 1998 that benefited Tom Hicks, Ross Perot Jr., and a slew

of developers; and a business editor at the paper forced to step down

after, among other things, he resisted giving preferential coverage to

the Belo company itself.

The News won a Pulitzer for

breaking news photography this year, its first in a decade that saw the

departure of many of its best reporters. Adams left in 1992. Two years

later, Hanners moved to the St. Paul Pioneer Press. In 2001, Reaves left to edit the alternative Fort Worth Weekly,

which has a circulation of about 60,000. Malone joined her a year

later, and both are convinced they made the right decision. Malone no

longer has the resources he had at the News, “but I can work

on stories that make a difference,” he says. “That’s what I want to do

with my career—to make a difference. I had lost that ability at the Dallas Morning News.”

IN

THE SPRING OF 2001, Robert W. Decherd, chairman, president, and CEO of

Belo, asked Jim Moroney if he wanted to be publisher of the Dallas Morning News. Moroney responded: “You’ve got to be kidding.”

He had good reason to be stunned. Like Decherd, Moroney is a great-grandson of G.B. Dealey, the founder of the News. But in his 23 years with Belo, he had had almost no news or newspaper experience. His background is in sales and television.

Still,

Decherd thought he had the right man. “Jim Moroney has spent his entire

professional life believing in and implementing a philosophy that our

news product defines our company,” he says.

In May 2001, Decherd announced Moroney as publisher and Mong, a 22-year veteran of the News,

as editor. Moroney first focused on advertising, marketing, and

finance, installing his own choices as bosses. Mong ran the news side

with managing editor Stuart Wilk, whom Mong had brought to the News from the National Enquirer in 1980.

Even

though he initially stayed away from the news side, Moroney says he

sensed some trouble there. “I had always heard there were sacred cows

at the Morning News,” he says. “You put that notion in a

newsroom, and you are on a downward spiral toward mediocrity.” Moroney

says he asked Mong if that were true; Mong said no. “Everything I ever

felt that needed to be in the paper, got in the paper, from the time I

was managing editor” in 1990, Mong said. Wilk, who replaced Mong as

managing editor in 1996, agrees.

But try persuading Todd Bensman

of that. Beginning in 1999, Bensman wrote dozens of hard-hitting

stories about Terrell Bolton, Dallas’ first black police chief. The

stories reported that Bolton may have ordered the police to ease

enforcement at a topless bar; that Bolton tried to have the head of the

Dallas FBI office transferred; that Bolton improperly demoted several

top commanders, prompting a federal lawsuit that cost the city millions

of dollars.

Some black community leaders were outraged. In the

spring of 2001, Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price and two

dozen other protestors staged demonstrations in front of the News’ headquarters—including setting newspapers on fire.

Bensman,

now an investigative producer for CBS Channel 11, says Bolton and his

allies pressured management to stop the stories. And, he says, it

worked: “In July 2001, the city editor told me, ’You are never to write

about Terrell Bolton again.”’

Egerton, brought in as Bensman’s

editor, confirms that management obstructed coverage of the police

chief. “I do know that stories were being killed. Some were edited to

death,” he says. “Management succumbed to political pressure. It was

extremely disturbing to people in the newsroom.”

Nonsense, says

Wilk. “There were no stories about Bolton that met our reporting

standards that we failed to publish,” he says. Bensman wrote 31 stories

about Bolton between November 1999 and July 2001. During the next six

months, he wrote not a word about the chief. This despite a tip he got

in September 2001: a source told Bensman that the Dallas police had

arrested more than two dozen Hispanic men for dealing drugs—cocaine and

methamphetamine, according to tests done by the cops. But, said the

source, the district attorney’s office determined that the “drugs” were

gypsum.

Bensman said he knew he would not be allowed to pursue

the tip, so he sent an e-mail to the appropriate editor, hoping another

reporter would be assigned to the story. Months passed. In November,

two reporters, Holly Becka and Tim Wyatt, who covered the Dallas County

district attorney’s office, got tips on the same story from separate

sources. They, too, informed their editor, who said she had it covered.

Six

weeks later, ABC Channel 8 broke the story—resulting in the revocation

of charges against more than 50 defendants. For its work, the

television station, also owned by Belo, was awarded the duPont-Columbia

and Peabody awards, the highest honors in broadcast journalism. Wilk

concedes that the newspaper should have broken the story. “We clearly

did not handle it as aggressively as we should have,” he says.

Wyatt

got a new tip in February: in 2000, beer distributor and philanthropist

Bill Barrett had been kicked and scratched by his wife. Angie Barrett—a

board member of a battered-women’s shelter and a convicted felon—was

charged with assault. Bill Barrett had asked District Attorney Bill

Hill—who had received $2,000 in campaign contributions from him—to drop

the charge. It was dismissed, six days after being filed, despite a

tough policy on prosecuting domestic abuse. Wyatt wrote a story.

Bill Barrett, whose family had contributed $250,000 to the Dallas Morning News

charity fund drive, says he asked Mong and Wilk to kill the story. They

did. Wyatt was devastated: “The message sent was that the story was a

sacred cow, and we couldn’t touch it.” Mong and Wilk say Barrett did

not get favored treatment. A few weeks later, two reporters at the

paper wrote a story about a district attorney in a neighboring county

who chose not to prosecute two campaign donors accused of assaulting

their spouses. The News ran it on page one.

Jeffrey Weiss, a religion reporter at the News,

is a 16-year veteran. He is no rebel, but he understands the ripple

effect when a story is stepped on. “You don’t have to be bit more than

once before you decide not to go back,” he says. “The people who pursue

investigative reporting at the Dallas Morning News do so out of an excess of determination.”

ON NOVEMBER 7, 2002, Mong delivered a speech to several hundred employees of the News,

in the same hotel where Moroney would give his “Revolution” speech 14

months later. Mong, like Moroney, made a long speech. Like Moroney, he

called for improvement: “Don’t you think we can be so much better?” he

said. “You and I know that we can be.” But he also defended the paper

against “voices in our newsroom, speculating” that the News

was slipping and was not as good as it was 10 years ago. “Clearly, in

nearly every measurable way, we are far better today,” he told the

crowd, ticking off more than a dozen areas of coverage. The audience

responded with polite applause.

These days, Mong endorses Moroney’s call for a revolution in the culture of the News,

and he believes he is the right person, with the publisher, to lead it.

Moroney agrees. He says that several months ago, Mong put together a

list of people who they “are methodically trying to attract to the

newspaper to increase the number of great journalists.”

Nearly a year after Mong’s speech, on October 31, 2003, Moroney held a brown-bag meeting with some 18 News reporters. Managers were barred. The publisher and the reporters talked for two hours. “Unprecedented,” Weiss says.

Reporters

hesitated to open up until Moroney assured them that there would be no

retribution for what they said. Finally, one reporter told the

publisher that “we have a climate here in which reporters are treated

with contempt.” Reporters talked about stories killed, delayed, or

watered down. “We told him we thought the paper was in real trouble and

that the news operation was weak,” Egerton says. To fix it, he added,

“there has to be a change in leadership.” Moroney promised change.

At first the rebuilding moved slowly. Keven Anne Wiley was hired away from the Arizona Republic

to rejuvenate the editorial page. Maples was allowed to more than

double her projects staff to five. But then came the serious shake-up,

on April 29. At 8:20 a.m., Mong met with the paper’s management council

and outlined more than a dozen changes. Among them, the new managing

editor was Rodrigue, 48, the head of Belo’s news operations in

Washington, D.C., and the only reporter to win two Pulitzers at the

News; the new Metro editor would be someone from outside the News, the first time that has happened in more than 50 years.

These

changes, Mong says, mark the start of the revolution. The newsroom

remains on high alert. “What Moroney has done is create expectations,”

Weiss says. “He could just as easily fail as succeed.”

Craig Flournoy was an investigative reporter for the News for 22 years. He is an assistant professor of journalism at SMU.

A longer version of this story appeared in the Columbia Journalism Review, May/June 2004. Copyright 2004 by Columbia Journalism Review.

Photo: David Woo/Dallas Morning News