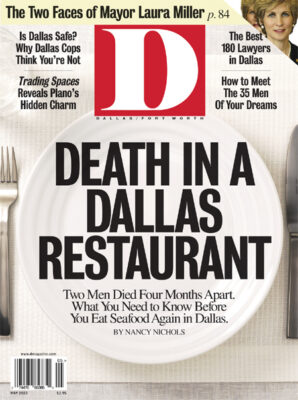

Two people died less than four months apart after eating raw oysters at a local seafood chain. Their last hours were almost more horrific than imaginable. Could a few dollars have saved them?

The nausea hit Gene in Shreveport. They were in the casino at around 8 p.m. when he said that he didn’t feel well. He told the others to go on to dinner without him. He would meet them later. When Gene hadn’t reappeared by 11 p.m., Mickey went up to the room to check on her husband. She found him shaking with chills and throwing up in the bathroom. Assuming it was just a bug, the couple went to bed and managed to make it through an uncomfortable night.

The nausea hit Gene in Shreveport. They were in the casino at around 8 p.m. when he said that he didn’t feel well. He told the others to go on to dinner without him. He would meet them later. When Gene hadn’t reappeared by 11 p.m., Mickey went up to the room to check on her husband. She found him shaking with chills and throwing up in the bathroom. Assuming it was just a bug, the couple went to bed and managed to make it through an uncomfortable night.

The next morning, though, Gene woke up feeling worse. His legs ached, his temperature shot up, and he had an insatiable thirst. Concerned that he had some sort of circulatory problem. Mickey called their daughter Danyelle back in town and told her to make an appointment with their family doctor. Around 10:30 on Tuesday morning, with Gene lying across the back seat of the car with his feet elevated. Mickey took the wheel and sped back to North Richland Hills.

They made it home a few hours before their scheduled appointment, and Gene went to lie down. As Mickey helped into bed, she noticed huge blisters on his legs and ankles. She loaded Gene back into the car. By the time the couple reached their doctor, Gene’s legs were black and blue, and they hurt so much that he cried out when anyone touched him. The doctor was perplexed by the symptoms and sent Gene directly to North Richland Hills Hospital.

In the critical-care unit, Gene became delirious from the pain and was unable to stand on his own. Now the blisters were rupturing. There was panic in the room as doctors frantically tried to make a diagnosis. A doctor asked for Gene’s medical history. Mickey said that Gene was basically in good health, but, a few months earlier, her husband had learned that he had liver damage. Another doctor asked what Gene had eaten over the last few days. Mickey struggled to recount his meals, but she finally remembered: the oysters. A culture confirmed that Gene was infected with the deadly Vibrio vulnificus bacterium.

Doctors treated Gene with an aggressive regimen of high-powered antibiotics all day Wednesday but with little success. Mickey spent Wednesday night in the hospital’s waiting room, hoping for good news that never came. The bacteria were multiplying like mad in Gene’s bloodstream, discharging toxins that sent him into septic shock. Eventually Vibrio spread to his lungs, liver, and brain.

On Friday afternoon, five days after the Dixons had lunch at Rockfish, Mickey began calling family members to tell them that the doctors didn’t think Gene would make it through the night.

What made Gene Dixon so sick was the strange practice of eating raw oysters. Our romance with the oyster has been documented for more than 2,000 years. In ancient Greece, they were served as an incentive to drink. Romans imported them from England and placed them in salt pools where the oysters were fattened with wine and pastries. Many Asian cultures still consider them an aphrodisiac.

Literature is full of sentimental references. They range from Ernest Hemingway (“As I drank the cold liquid from each shell and washed it down with the crisp taste of wine, I lost the empty feeling and began to be happy and to make plans” ) to Woody Allen (“I will not eat oysters. I want my food dead. Not sick, not wounded, dead.”).

“An oyster is the only animal protein that we consume live,” explains Dave Blevins, the Food and Drug Administration’s regional shellfish specialist. “If you pop the top off you have a filter-feeding animal with a beating heart.” And other organisms live in those shells, too.

Vibrio vulnificus is a naturally occurring bacterium found in oysters harvested from warm, shallow, coastal saltwater. Vibrio can cause gastroenteritis in any healthy person, but it can kill someone who has health problems such as diabetes, cancer, HIV, heart ailments, transplanted organs, hepatitis, or other liver diseases—conditions that many people don’t even know they have, as they can go undetected for years.

Vibrio can also pose a risk to people who have low levels of stomach acid (from taking too many antacids) and to those who use steroids (for arthritis or asthma). The mortality rate is 50 percent for those who become infected with Vibrio and who already have compromised immune systems, making Vibrio the most lethal foodborne killer. The FDA estimates that 12 to 30 million Americans are susceptible.

So it might sound surprising that only about 20 Americans die each year from Vibrio blood infections. Far more surprising, though, is that in 2002, not one, but two Dallas-area residents died within three and a half months of each other after eating raw oysters—and the families of both people say that they ate those oysters at a Rockfish Seafood Grill, a chain based here. Whether these two deaths were the result of negligence or simply an unfortunate coincidence, the courts will decide. But one thing is certain: if you order Gulf Coast oysters at any restaurant—and if you want to survive the meal—you’d better know how they got to your table.

ON A GRAY AND WINDY FEBRUARY MORNING, Clifford Hillman stands on the dock behind his Hillman Oyster Company, in the tiny community of Dickinson, on Galveston Bay. There are 49 licensed shellfish processing plants scattered among the oil refineries and trailer parks that line the Texas Gulf Coast. Many do business in small, unincorporated areas where the streets are made of crushed oyster shells, and huge clouds of smoke billow in the distance. Ubiquitous sea gulls cry as they scavenge through 20-foot-tall piles of discarded half shells.

“I have a theory,” Hillman says, pulling the collar of his denim jacket up around his ears. “When people are running from anything and they reach the waterfront, they can’t go any farther unless they care to swim. So they all stay. That’s why any waterfront community is a melting pot. Around here, where people don’t have to abide by hard, formal regulations and rules that you would have in a normal society or incorporated city, people live simply in the rural parts where it’s easy to hide.”

Hillman is waiting to meet today’s haul from the oyster reefs. The boats that left before dawn are returning early, driven back to port by deep swells and high winds. On a good day, the boats spend about 14 hours circling 10 to 20 miles offshore, using a dredge with 5-inch teeth that skims the reefs for the gray bivalves that contribute nearly $35 million to Texas’ $596 million shrimp and oyster industry. It’s a hard way to make a living.

As they search for beds that haven’t been overfished, captains also have to be mindful of which areas are officially closed due to poor water quality. The Texas Department of Health monitors the water in the 14 shellfish-growing areas off the coast. Each year in the Gulf of Mexico, nearly 10 million pounds of toxins—oil-refinery byproducts, farming pesticides, heavy metals, and fecal bacteria from raw sewage—become locked into ocean sediments and remain potent for a long time. The TDH usually sends testers out twice a week to sample the safety of the Gulf waters. Badly contaminated areas are closed because these filter feeders pump large volumes of water, and they pick up and concentrate disease-causing bacteria and viruses if they happen to be bedded in polluted waters. (Testing had stopped indefinitely during my visit: one day before my arrival, the local TDH office burned to the ground. A gas can had been left amid overturned filing cabinets. At press time, an investigation was still underway into what appeared to be a clear case of arson.)

As they search for beds that haven’t been overfished, captains also have to be mindful of which areas are officially closed due to poor water quality. The Texas Department of Health monitors the water in the 14 shellfish-growing areas off the coast. Each year in the Gulf of Mexico, nearly 10 million pounds of toxins—oil-refinery byproducts, farming pesticides, heavy metals, and fecal bacteria from raw sewage—become locked into ocean sediments and remain potent for a long time. The TDH usually sends testers out twice a week to sample the safety of the Gulf waters. Badly contaminated areas are closed because these filter feeders pump large volumes of water, and they pick up and concentrate disease-causing bacteria and viruses if they happen to be bedded in polluted waters. (Testing had stopped indefinitely during my visit: one day before my arrival, the local TDH office burned to the ground. A gas can had been left amid overturned filing cabinets. At press time, an investigation was still underway into what appeared to be a clear case of arson.)

The fishermen also face the game wardens from the Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife who patrol the forbidden waters and board boats to inspect catches. But with so many beds barren and competition tough, some fishermen operate in outlawed areas. They can always find a processor who will buy their catch without questioning its provenance.

In the distance, a cloud of gulls swirls above an incoming boat. The air is filled with the chugging of diesel engines as the battered boats back up to the docks. The sharp shouts of Vietnamese fishermen dressed in ski masks clash with the Spanish spoken by those on the docks. It’s a turn-of-the-century scene from a Scorsese film—a world of shady characters and shadier business deals. Fishermen share stories about which processors will pay for illegally harvested oysters and which dealers will take care of the tickets written for infractions.

Hillman’s yard managers amble out of the office to assess the day’s catch. “Three, six, nine, 11 sacks,” Hillman counts. “Bad, bad, bad day. An average day is 40 or 50 for them.”

There are a few tense moments as the managers board the boats and inspect the filled burlap sacks. They look at the size of the oysters first, then dump the contents on the deck and insert a bottomless wire bushel basket into the mouth of a sack. A fisherman shovels the oysters back into the sack until they hopefully reach the rim of the bushel basket. If they don’t, Hillman has the option of checking every sack or offering the captain a lower price.

Today several sacks fall short, but Hillman says, “It’s dangerous work in rough waters. They didn’t even come close to paying for fuel. It’s depressing for them. I’ll give them a break, and then I know they’ll come back to me.”

One of Hillman’s yard managers pulls a short knife from his pocket and effortlessly shucks open a palm-sized oyster with gloveless hands. He tosses back the mollusk, and there’s a noticeable sigh of relief as he signals a thumbs up to the captain.

Once the catch is approved, the sacks are tagged with where the oysters came from, the boat’s license number, and the captain’s name. One Vietnamese captain complains about the unmarked 18-wheelers with Mississippi license plates that routinely drop off 200-pound bags of oysters at unscrupulous Texas processors who tag them as a local catch and ship them to customers all over the country. “They take the food out of my mouth,” he says. By illegally tagging oysters, these processors put people’s lives at risk. In many cases, they have no idea when the oysters were actually harvested or how many days they’ve spent on the truck or even if the truck has been properly refrigerated.

With so few bags to unload today and the temperature in the low 40s, Hillman doesn’t worry about the oysters overheating. That danger comes in the hot summer months, when thousands of bags hit the shore at the same time. Oysters must be in the refrigeration units within two hours, or else the bacteria could multiply to the point where food poisoning becomes a real risk.

From the docks, the oysters go by forklift to the processing plant, the most crucial leg in the oyster’s journey to the table. How a raw oyster is processed can make the difference between a good meal and a deadly one. At Hillman’s, the oysters first go to the picking house, where they are hit with a high-pressure wash, put on a conveyor belt, and inspected for cleanliness. Workers with culling tools break off bad shells and separate oysters that have become attached to each other. Then they move to the shucking house, where the sound of shells hitting stainless steel is deafening. Two lines of 20 men sit on stools, facing piles of oysters, shucking like robots: oyster, knife, twist, oyster, knife, twist. The discarded shells clank onto a conveyor belt that carries them outside. The half-shelled oysters go onto trays and are then whisked to a rinsing station, where workers with ceiling-mounted waterspouts wash away any remaining bits of mud or shell. From there, the cleaned oysters move on trays through a 12-foot, stainless-steel freezing tunnel, where they are “quick frozen” to minus 109 degrees. As they exit the tunnel, the oysters are sprayed with water that forms an ice glaze. Once frozen, they are packed into insulated boxes and stored in the freezers to await distribution.

Hillman owns two of the only three Texas processing plants that use a post-harvest treatment like quick freezing to reduce Vibrio vulnificus to non-detectable levels. (His other is located in Port Lavaca.) He also processes oysters for raw consumption only during the cooler months. According to an FDA report, nearly all illnesses linked to raw oysters have been traced to those harvested from the Gulf during the warmer “non-R” months, May through August. Hillman was the first to integrate cryogenic technologies into oyster processing in the late ’80s. Since then, two other methods have emerged to produce risk-free oysters. In “cool pasteurization,” oysters are immersed in warm-water tanks calibrated to kill bacteria (145 degrees for 15 seconds), and then they’re submerged in ice water to prevent cooking. In the “high-pressure process,” oysters essentially shuck themselves under 40,000 psi of hydrostatic pressure. This kills pathogens, too, and the shells are banded back together.

Hillman owns two of the only three Texas processing plants that use a post-harvest treatment like quick freezing to reduce Vibrio vulnificus to non-detectable levels. (His other is located in Port Lavaca.) He also processes oysters for raw consumption only during the cooler months. According to an FDA report, nearly all illnesses linked to raw oysters have been traced to those harvested from the Gulf during the warmer “non-R” months, May through August. Hillman was the first to integrate cryogenic technologies into oyster processing in the late ’80s. Since then, two other methods have emerged to produce risk-free oysters. In “cool pasteurization,” oysters are immersed in warm-water tanks calibrated to kill bacteria (145 degrees for 15 seconds), and then they’re submerged in ice water to prevent cooking. In the “high-pressure process,” oysters essentially shuck themselves under 40,000 psi of hydrostatic pressure. This kills pathogens, too, and the shells are banded back together.

“Converting over was a difficult challenge,” Hillman says. “We starved to death for five years.” But now he says he can sleep at night knowing that no one will die from eating a raw oyster processed at his plant. “Everyone wins. Chefs and restaurants don’t have shelf-life concerns, and the labor involved in shucking the oyster is already done.”

Just a few miles east of Hillman’s plant, at a place called Misho’s Oyster Company, things are done differently. Located in the city of San Leon, at the end of a lonely stretch of road lined with mobile homes on stilts and headless palm trees, Misho’s processing plant is virtually barricaded by gray mountains of oyster shells. A small, hand-painted sign on the curb is the only business marker.

Today, workers inside the metal-sided plant are shucking oysters to be used in cooking—the only truly safe way to consume oysters. Toward the end of a shift, a group of 12 shuckers dressed in flannel plaid shirts, sweat pants, and white rubber boots sit on footstools amid pools of water and bits of shell. The men knife the animals, remove the meat, and plop the edible bits into a stainless-steel pot at their feet. Once the pot is filled with 8 pounds of oyster meat, they take it to a window where another worker weighs it and hands the shucker a receipt. He then returns with an empty pot and starts again. The workers are paid $1 a pound, and a skilled shucker can produce about 10 pots, or 80 pounds, a day.

Unlike Hillman’s plant, Misho’s features no high-tech machinery. Oysters destined to be eaten raw go through here without any post-harvest treatment to combat Vibrio. And the owner himself, a large, brash Croatian man named Michael “Misho” Ivic, is one of the more colorful characters in Galveston Bay’s oyster business. Several Dallas seafood distributors say they won’t buy oysters from Misho.

“Misho’s has a bad reputation,” says one veteran who would only comment anonymously. “The word on the street is that his oysters have been known to kill people every year. I heard two people died last year from his stuff.”

In fact, Texas Department of Health records indicate that the oysters Gene Dixon ate last July at the Rockfish in North Richland Hills, the oysters that killed him, came from Misho’s Oyster Company. Then, in October, when another Dallas area man died after eating raw oysters at a Rockfish, those were also supplied to the restaurant by Misho’s.

JAMES WHITE, A 52-YEAR-OLD STEEL DETAILER from Lancaster, ate at a Rockfish in Cedar Hill. He and his wife Suzanne had invited their daughter and son-in-law to dinner to celebrate good news. The Whites had just learned that their daughter was pregnant. Although James had been diagnosed with cirmorial Hospital in Dallas, where doctors soon began to suspect he was infected with Vibrio vulnificus. His death, like Gene Dixon’s, was horrific. In their final hours, the men were covered with lesions that were all the more gruesome because they looked like oysters. As primary septicemia grew worse and their bodies swelled with poison, the skin on their arms and legs split open.

On December 4, 2002, Mickey Dixon filed a lawsuit against Rockfish and Brinker International, the Dallas-based casual-dining conglomerate, which had formed a partnership with Rockfish in July 2001. At that time, the 4-year-old franchise started by Randy DeWitt and his wife Michele had just opened its eighth location. Prior to Rockfish, the couple had operated three locations of Shell’s Oyster Bar before morphing the fourth location into the original Rockfish and selling the Shell’s concept to former partner Bill Bayne. Today, boosted by the capital of Brinker, Rockfish now has 19 locations (17 in Texas and two in Arizona) and plans to operate 22 units in the Dallas area.

When I visited DeWitt in February, there had been no publicity about the lawsuit (and still none, as of press time). Rockfish’s PR machine had sent out invitations to media offering time to talk with DeWitt about the restaurant’s new location in South Arlington. On the 10th floor above Mockingbird Station, the Rockfish offices, like the restaurants, are decorated in a kitschy, fly-fishing motif. DeWitt was dressed in a periwinkle blue shirt. The affable 44-year-old and graduate of Jesuit High School gazed on the Dallas skyline as he talked.

“We really set out to have fun with this restaurant,” he said. “I literally went to flea markets and bought old 1930s Field and Stream magazines and framed them. We put in river rocks and rock-and-roll.” The restaurants were an instant success. “When we opened, we had enthusiastic customers who came back the next day. Then they came back with their friends. It was the greatest thing ever.”

Just as the company was cresting, though, Gene Dixon died. When asked about the circumstances, DeWitt’s face turned white and tears filled his eyes. “We don’t sell unpasteurized Gulf oysters any longer,” he told me. “I wish we’d always sold these [pasteurized] oysters, but we didn’t. We didn’t know enough at the time.”

DeWitt went on to claim that he’d heard about deaths resulting from contaminated oysters in two other popular Dallas restaurant chains. D Magazine filed a Freedom of Information Request with the Texas Department of Health to confirm which restaurants across the state have served oysters that killed people, but the department failed to release the documents before press time. However, two deaths were uncovered at two different locations of Landry’s Seafood House (one in April 1999, in Galveston, and one in May 1999, in Kemah). In both cases, the oysters were traced back to Misho’s. In the Kemah death, the oysters had been harvested from a closed area.

Mickey Dixon claims that Rockfish and Brinker, which operates more than 1,100 restaurants worldwide, were negligent in serving raw, untreated Gulf Coast oysters during warm-weather months.

Rockfish no doubt will counter that both men had existing medical conditions that put them at risk and that the oysters were sold as required by law, with a warning printed right on the menu. And industry experts will defend even oysters shipped from Misho’s plant, which has also supplied oysters to many other popular local restaurants, including Pappadeaux and Joe’s Crab Shack. That two deaths occurred months apart in one restaurant chain, they will say, is merely bad luck. “It’s like being struck by lightening twice,” Clifford Hillman says. “It’s just an unfortunate luck of the draw,” says Dave Blevins of the FDA.

The Dixon suit is still in the discovery phase. But no matter how it (or a possible White suit) turns out, it’s obvious that the Gulf Coast oyster industry, as a whole, needs retooling. In essence, the shellfish industry today is self-regulated. It’s a classic case of the inmates running the asylum. Although the FDA visits each state once or twice annually to grade the state health inspectors while they inspect a processing plant, for almost 20 years the agency has relied on an association of state health officials—the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference (ISSC)—to set national safety policies and carry them out. For much of that time, the ISSC, in conjunction with the National Shellfish Sanitation Program (also run by volunteers within the industry), has debated ways to reduce the occurrences of Vibrio vulnificus infections, but the death rate has remained unchanged.

The resistance to requiring all processors to put their oysters through post-harvest treatments springs from two places. The first is people’s taste buds. Purists argue that there is no comparison between the taste of a fresh Gulf Coast oyster and one that has received a post-harvest treatment. “Ever put a penny in your mouth?” asks local seafood whiz and chef Chris Svalesen, of the recently closed Thirty-Six Degrees on Lemmon Avenue. “That’s what a pasteurized oyster tastes like.” All the post-harvest treatments do require opening the oyster long before it reaches the table. Whether that affects the taste is a slippery debate.

Besides the taste of post-harvest-treated oysters, the cost of such treatment is the other source of resistance to changing the industry. Post-harvest treatments to a Gulf Coast oyster bump it into the same price point as the high-end, cold-water varieties. While untreated Gulf Coast oysters sell wholesale to restaurants and markets for around $15 for 100-count, chefs expect to pay $45 for 100-count for Blue Points, which are harvested in Long Island, New York. Ameripure, one of the largest processors of pasteurized oysters, sells their oysters for around $35 for 100-count. The quick-frozen oysters on the half shell run $60 for 144. At press time, Gold Band oysters, which undergo the high-pressure post-harvest treatment, were not available locally. That puts Gulf Coast oysters at a price point about one-third of the cost of those that have received post-harvest treatments. Chances are, if you are paying less than $1 per oyster, they are untreated, although many restaurants price expensive oysters at or under cost.

“The true, hardcore oyster people like the Gulf oyster because they are cheaper, and it’s the way it’s been done for hundreds of years,” says Nick Papa of Fruget Aqua Farms and Seafood, an Arlington-based seafood distributor. “If any federal or state regulatory agency would come in and issue a mandate that they could only use treated oysters, you’d see oyster sales drop by 75 percent.”

The industry says that treating every oyster after harvest would be cost prohibitive. But according to the FDA, deaths and illnesses from Vibrio vulnificus cost the United States approximately $120 million per year. Based on that information, a group called the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) recently concluded in a study that the annual cost to the industry of treating its oysters to destroy Vibrio vulnificus—approximately $14 million—is minuscule by comparison. By adopting the available technologies, the RTI concludes that the industry would actually save close to $2 million annually.

As long as serving raw Gulf Coast oysters presents a risk, cautious local chefs and restaurateurs will go with the alternatives. Svalesen won’t serve raw Gulf Coast oysters at all. “I prefer varieties like Blue Point that are harvested from sandy bottom areas, in cold, churning water,” he says. “Most of the Gulf oysters have been sitting in polluted mud.”

At TJ’s Fresh Seafood Market on Preston Road, they take the extra step to educate their customers. Karen Alexis, who co-owns the shop with her husband Pete, says she has people who still insist on Gulf Coast oysters. “We have plenty who grew up eating Gulf oysters,” she says. “And I will special-order them. But I always give customers a verbal and written warning about the risk of consuming them raw.”

Food consumption has always been a risky business. Each year, hundreds of cases of food poisonings, such as salmonella, E. coli, and botulism, are reported. A single restaurant omelet may contain eggs from hundreds of chickens; a chicken carcass can be exposed to the dripping juices of thousands of birds.

But the next time you consider ordering the Gulf Coast oysters on the half shell, you would do well to ask yourself a few questions first. Are you absolutely certain you don’t have HIV, cancer, or cirrhosis? How about diabetes? Hepatitis? Do you know where in the Gulf, exactly, the oysters came from? Have they gone through a post-harvest treatment? Does the current month have an “R” in it?

If the answer to any of those questions is no, it’s probably better to pass on the oysters. As Dave Blevins says, “We should all be concerned about eating raw oysters because illness is preventable. If one person dies, it’s one too many.”