THE DAY WRIGHT SIGMUND CAUGHT FIRE, HE was supposed to move an ice maker. The 21-year-old college student from Dallas was interning for the summer at his father’s Washington, D.C., insurance company, where a deliveryman had left the 80-pound machine in the firm’s underground parking garage. Wright planned to use his dad’s second car, a white 1996 Chevy Blazer festooned with Washington Redskins decals and “The Chief” painted in huge letters on its tailgate. Donald Sigmund was waiting for his son at his new $1.3 million home in Georgetown. He was readying the place for a special occasion. His fourth wife and her two children were moving in that weekend.

THE DAY WRIGHT SIGMUND CAUGHT FIRE, HE was supposed to move an ice maker. The 21-year-old college student from Dallas was interning for the summer at his father’s Washington, D.C., insurance company, where a deliveryman had left the 80-pound machine in the firm’s underground parking garage. Wright planned to use his dad’s second car, a white 1996 Chevy Blazer festooned with Washington Redskins decals and “The Chief” painted in huge letters on its tailgate. Donald Sigmund was waiting for his son at his new $1.3 million home in Georgetown. He was readying the place for a special occasion. His fourth wife and her two children were moving in that weekend.

Wright’s life changed forever that Friday, July 12 of last year, when he stepped into the driver’s seat. He remembers a series of moments: first, he heard a pop. Then orange sparks and flames shooting from the vents in the dashboard, which began to melt. Airbags inflated. An explosion from behind—or maybe beneath him.

Engulfed by fire and shrapnel, Wright threw himself out of the Blazer and ran. His clothes were on fire. Wailing and flapping his arms, he tried to take off his shirt. He saw an old woman about five cars down, sitting behind her steering wheel, her hands on her face, screaming, “Help! Help! Help!”

Wright kept moving. He stopped, dropped, and rolled, but that didn’t work. So he got up and ran another 30 yards to the garage entrance, where two parking attendants saw him and ran the other way. “He’s on fire! He’s on fire!” one of them shouted.

The yelling caught the attention of Tony Richardson, a 29-year-old repairman who was working aboveground on the garage’s broken door. He had been cutting metal and hadn’t heard the explosion. Richardson ran down to the bottom of the ramp, where Wright was stomping and slapping himself, still trying to put out the flames. His hair was singed, his eyebrows mostly gone, and though he got his shirt off quickly enough, his khaki slacks were reduced to a pair of blackened cut-offs and two anklets of flaming cloth. Richardson got on one knee, turned his head from the heat, and helped Wright slap out the remaining fire.

“Okay, buddy, you’re going to be okay. Have a seat,” Richardson said, directing him to a ledge.

As Wright tried to move, he moaned. “I can’t,” he said. “My butt, my butt.”

That’s when Richardson turned him around and realized the true extent of Wright’s injuries. He saw yellow fatty tissue, red blood, and the horrifying white of his lowest vertebrae.

“My God, his whole ass is gone!” Richardson yelled to his co-worker above. “Call 911! Call 911! Call 911!”

Richardson ran back up the ramp and grabbed an armload of terrycloth rags from his truck. Remembering something he saw on the Discovery Channel, he had Wright bend at the waist and brace his hands on the ledge. Then Richardson stuffed as many rags as would fit into the gaping wound where Wright’s buttocks used to be, applying as much pressure as possible. The two waited like that for the paramedics to arrive.

“What’s your name?” Richardson asked. “How old are you? Do you work in the building? Where was the car parked?”

He kept asking questions to keep Wright conscious. The paramedics seemed to be taking forever. Wright was surprisingly calm and coherent, able to remember his father’s cell phone number. He said he was thirsty, and one of the several bystanders brought him some water. Then another explosion—the Blazer’s gas tank—from inside the garage. A few seconds later thick clouds of black smoke poured out of the garage opening.

The fire department arrived in 10 minutes and the paramedics about five minutes after that. D.C. police cordoned off a four-block area in the Friendship Heights neighborhood. An ambulance took Wright to Washington Hospital Center, arguably the best burn center in the United States. (It’s where the 9/11 Pentagon victims went, and its director, Dr. Marion Jordan, trained under the founder of Parkland Hospital’s famed burn center in Dallas.)

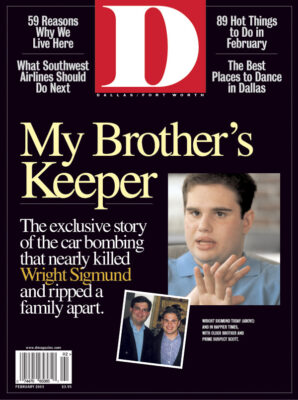

A husky kid with short dark hair and distinguishingly thick lips that frame a quick smile, Wright arrived at the ER completely scorched, speckled with black bruises, and grotesquely inflated. The body’s response to severe burns is to swell up like one giant blister. Doctors rushed him to an operating room and sliced a trough down his right leg, hip to ankle, to drain the fluid. They then made a 7-inch vertical incision in his gut, peeling him open to check for shrapnel damage to vital organs and re-route his colon away from the damaged part of his body. With the end of his digestive track attached to a hole near his appendix, the doctors began the debridement process—scraping away charred skin and necrotic tissue with a wire brush and a rasp-like instrument, then powdering him with antiseptic silver nitrate.

His mother, Claire Stanard Phillips, arrived at the hospital from Dallas around 1:30 a.m. Saturday. She met her ex-husband Donald in the waiting room. Two D.C. cops were stationed outside the ICU. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms agent Robert Poole introduced himself as the lead investigator on the case. He had 40 agents working on it, he said. All they knew so far was that the bomb was a relatively crude device, but it was powerful. He told Donald and Claire that pipe-bombers are almost exclusively 25- to 35-year-old white males.

Wright would regain consciousness in a couple days. Tubes in his throat prevented him from speaking. A doctor put a pen in Wright’s hand and held out a pad of paper.

“Am I going to live?” Wright wrote. The doctor said yes, even though Wright’s chances were probably 50-50. “What about my dick?” he wrote next. The doctor smiled to let him know everything was fine down there, even though his testicles looked like purple-black grapefruits. That sort of swelling is what happens when you get third-degree burns on 20 percent of your body, he explained. The skin wasn’t burned, and the shrapnel missed his genitals by about half an inch.

Most of the rest of the family met Claire and Donald at the hospital Sunday morning. Wright was only semiconscious at this point, and only immediate family was allowed in to see him. Wright’s 34-year-old brother Scott had been in to see him on Saturday. Like the rest of the family, he had to show ID and give a password—”Kerlix”—the name Wright was checked in under to keep any potential assailants and the media away. But when Scott came by Sunday, one of the officers looked down at his clipboard where he had a memo: “Prescott William Sigmund is not to be allowed into his half brother Donald Wright Sigmund’s room at any time.”

Their father erupted. “You’ve got to be f—ing kidding me! Claire, tell him this is Wright’s brother!” Donald and the officer argued for several minutes, Scott standing there, not saying a word. Finally, Donald said, “He’s my son and I’m going in and he’s going with me.” The officer let them pass, contacted his supervisor, and watched the room closely.

Earlier in the day, Wright’s other brother, Alex Jett, 26, had stepped outside into the hospital courtyard with Scott and a few other family members and friends. They were discussing who could be responsible for the attack. Could it really be terrorism? Maybe it was a hitman hired by a bookie. Everyone figured Donald, 65, was the target. The Blazer was his car, after all. As they speculated, Scott wandered about 20 feet away from the group, where he stood quietly with his 2-year-old son, feeding the pigeons.

WRIGHT WAS BORN TO CLAIRE AND Donald in Washington, D.C., in 1981. Donald was president of a boutique insurance agency, Wolf and Cohen Financial Services, which specialized in life policies for wealthy executives, and Claire was a press aide for Sen. Vance Hartke (D-Indiana). They had married in 1979, about a month after Donald divorced Gwendolyn, his wife of 16 years, with whom he had two children, Scott and Lindsay, both adopted as infants.

WRIGHT WAS BORN TO CLAIRE AND Donald in Washington, D.C., in 1981. Donald was president of a boutique insurance agency, Wolf and Cohen Financial Services, which specialized in life policies for wealthy executives, and Claire was a press aide for Sen. Vance Hartke (D-Indiana). They had married in 1979, about a month after Donald divorced Gwendolyn, his wife of 16 years, with whom he had two children, Scott and Lindsay, both adopted as infants.

The Sigmund family tree would spring more branches over time, with Donald eventually marrying four times and bringing a total of seven children into the fold. After Donald and Claire divorced in 1983, she moved to Dallas with Wright and pursued a career as a marriage and family therapist. Two months after the divorce, Donald married wife number three, Debbie, a young widow and mother of 8-year-old Alex. Two years later, they adopted Hillary.

“It really was like a Brady Bunch situation,” Debbie recalls. Her stepchildren, Scott and Lindsay, would come to spend weekends at the house. None of the siblings referred to each other as “half” or “step”. She says Scott had a unique role as the biggest brother, 19 years older than his youngest sister. “Scotty was so wonderful with all the kids,” she says, explaining that he was the only one who could get Hillary to do her homework. He also taught Alex how to ride a bike and drive a car. “When he was around, he was like another parent to me,” Alex says. “Scott was my anchor.”

Donald and Debbie became prominent D.C. socialites—raising money for the Washington Ballet and Kennedy Center, serving on their country club’s board, and hosting summer parties in Nantucket. But to television cameramen at RFK Stadium, Donald was best known as the guy in the Indian war bonnet and face paint. A third-generation season-ticket holder, Donald had 50-yard-line seats. He threw lavish tailgate parties, sometimes hiring a band to play in the parking lot. And during the game, cameras often focused on him as he cheered on the Redskins, beating a tom-tom.

Back in Dallas, Donald’s only biological child tried to stay connected. Wright talked to his brothers and father at least weekly and regularly joined them on fishing trips. Father-and-sons excursions in August became a family tradition, as Donald took the boys to Aspen, Alaska, and China. And, of course, there were always Redskins games. Donald, Scott, and Alex came to Dallas for Thanksgiving in 1990, when Wright was 8, to see the Redskins play the Cowboys. Donald and his three sons all dressed in Redskins jerseys and feathered headdresses as they paraded through Texas Stadium, drawing boos. Wright loved it.

That was the year Scott graduated from Washington and Lee University, Donald’s alma mater, in Lexington, Virginia. Like his father, Scott was a sociable fellow. He joined his father’s fraternity, Chi Psi. He was big and jolly and often stood behind the bar he and his roommate had built in their room, serving drinks while quoting Monty Python lines. He developed a taste for cheap beer and expensive bourbon. At a tavern called Old Glory in Georgetown, Scott’s name is listed along with dozens of others on plaques honoring members of the bar’s Bourbon Club, which requires its members to drink 80 bourbons from around the world. Scott completed the task twice.

Donald and Scott maintained what seemed to be a close relationship. Scott regularly made the three-hour drive to D.C. to join his father at Redskins games, and on Scott’s 21st birthday, Donald went down to W&L, throwing a cocktail party for the entire fraternity.

Scott got married three years out of school to a Latin and French teacher named Bradey Bulk and went to work for his father at Wolf and Cohen, as a vice president. “I was always so proud of him,” Donald says. “He was going to be the next generation entering the business.” But that would never come to fruition, as Donald fired Scott the next year, shortly after he botched a costly claim.

“Business and family don’t mix,” Donald said. “What really matters is the relationship between father and son. It’s for the best, Scott, for the both of us.”

Meanwhile, Wright was flourishing in Dallas, where he attended St. Mark’s School of Texas. (I first met him during his senior year, 1998-99, when I was a teacher at the school.) He was a standout student—solid academically and accomplished on the lacrosse field and wrestling mat. He was homecoming king. And he put in more than 100 volunteer hours his senior year at the Austin Street Shelter.

As a wrestler, Wright won the 1999 state championship in the 140-pound weight class. But the match he remembers most fondly was an early-round victory at Prep Nationals in Pennsylvania. Facing off against the top-ranked wrestler in the country, he was down with just seconds to go. But he pulled off an escape from the bottom position (1 point) and followed that with a double-leg takedown (2 points) to send the match into overtime and ultimately win in an upset. His dad drove up for the tournament and was cheering heartily from the packed stands.

After graduation from St. Mark’s—which Donald attended with Scott and their other brother Alex—Wright followed in the family footsteps to W&L. Being in Virginia allowed him to spend more time with his dad and Scott. (Alex had moved to Florida.) But he would learn that his dad was going through a difficult time. Debbie, wife number three, divorced him in March 2001, after 18 years of marriage. But Wright had no idea about Scott’s troubles.

Scott was working for a “human resource solutions” company called Motivano. He maintained a cheery demeanor that belied his rapidly deteriorating financial position. He had run up a five-figure debt by early 2001, at which point he borrowed $35,000 from his mother (Donald’s first wife) Gwendolyn. Then, in November, Scott was laid off from Motivano. But he told no one. Not his wife Bradey, not his friends, not his brothers—and certainly not his father. Instead, he said he was working from home. Each morning he put on a tie and retreated to a basement office.

Gwendolyn actually owned the two-story house in the posh River Falls neighborhood of Potomac, Maryland, where Scott and Bradey resided. They bought a condo in the same neighborhood and moved his mother there. An investigation would later reveal that Scott owed $190,000 on the condo and had let his household bills go unpaid for months. In his basement files, Bradey would find a sheet of paper on which Scott had practiced her signature until he got it down well enough to take cash out of her 401(k), almost $30,000. Scott also got an American Express card in Donald’s name and charged $16,000 on it. About six months prior to the bombing, Bradey and Scott were discussing how they would pay for the education of their children, Jack and Cole, ages 2 and 4. Not to worry, Scott told her. He stood to inherit about $300,000 when his father died.

Though no one in the family seems to have thought much of it at the time, Scott did begin to show personality changes. In March, four months before the bombing, he went to Delray Beach, Florida, for brother Alex’s wedding. Scott shared an ocean-view room with Wright at the Marriott.

“He was really cynical all weekend,” Wright says. “He was complaining a lot, like we were supposed to have a suite, not a ’normal-ass room.’” Alex thought it a bit strange that his brother didn’t give him a wedding gift, or even a card. Scott did, however, run up a $600 room-service tab, despite warnings from both of his brothers that Dad wouldn’t be pleased.

If Scott’s relationship with Donald seemed to be growing strained, the family figured he was simply bothered by his father’s latest relationship. In April, Donald unceremoniously married his fourth wife, 45-year-old Sara Strader. Few in the family were pleased with the nuptials. Scott was just taking it harder. In May, he did something truly bizarre.

For his 65th birthday, Donald invited all of his children and their spouses to the Greenbrier Resort in West Virginia. Conde Nast Traveler recently rated the Greenbrier the “Top Resort in the World for Golf,” and it also offers excellent facilities for hunting, fishing, and falconry. Prior to a celebratory dinner, the Sigmund family gathered in Donald and Sara’s suite. Each took a turn offering a few words of thanks and good wishes to the Sigmund patriarch, then presented him a gift. Wright gave him a shirt. Alex and his new wife Nicole arranged to have a saxophone player come to the room and play “Happy Birthday.”

When it was Scott’s turn to present, he stood up and recited a poem. He said he and Bradey wrote it together. It seemed at first like it might be funny, with what could be interpreted as an economy joke about how, instead of celebrating in the South of France for a month as originally planned, the family had come to West Virginia for a weekend. Everyone chuckled. But the sarcasm grew more biting as the poem rambled on for 10 minutes. It turned out to be a litany of nearly every infraction his father had ever committed—from extramarital affairs to his DWI arrests in 1997, 1998, and 1999. All rendered in rhyme.

“Everything about it was disrespectful,” Alex recalls. “I kept waiting for something nice in the poem, like a punchline or something, and it just didn’t come.”

When the berating ended, Scott gave a copy of the three-page poem to his dad, along with some childhood pictures. The family clapped awkwardly. Scott smiled.

One other incident stands out in Wright’s mind. Not long after the trip to Greenbrier, heading into his final year at W&L, Wright found himself interning in D.C. at his father’s firm. He enjoyed the insurance business more than he thought he would, and he began to see it is a real career option. Likewise, Donald was pleased with Wright’s work.

“For a summer intern who was the boss’s son, he didn’t act like either of those,” Donald says. “I’d leave at 4:30 to go to the health club and offer Wright a lift home, and he’d say, ’No thanks, Dad. I have stuff to do.’”

But just a few weeks before the bombing, Wright accepted his father’s invitation for after-work drinks at the Watergate Bar. Scott joined them. As usual, the Sigmund men talked about the Redskins and W&L. When Donald left the table briefly, Scott asked Wright how work was going, acknowledging that “Dad can be pretty rough.”

“It’s not so bad,” Wright said. “I’m working hard and learning a lot. I kind of like it.”

“Just don’t work too hard.” Scott said.

As Donald returned, Wright recalls, one of his dad’s drinking buddies approached their table and introduced himself. “You look just like your father,” he said to Scott.

“Oh, I’m not the one,” Scott responded. “I’m adopted. He’s the one. He’s his only real son.”

The comment seemed odd because Scott had never before distinguished himself from the family in such a way.

What Scott did over the next couple weeks, a federal jury in D.C. will have to determine. At this point, what is known is that on Wednesday, July 10, two days before the attack, The Chief was parked in its usual spot in the underground garage. That night, at 9:41, 19 minutes before the parking attendants went off duty, cell phone records indicate that Scott made a call from somewhere in D.C. to his voicemail. He would make two more cell phone calls that night: one at 12:21 a.m., from Bethesda to his voicemail; and another at 12:23, to his home in Potomac.

The call records merely make hints about what Scott could have been up to in the days before the bombing. Other evidence points directly at him. According to the ATF, the device in Donald Sigmund’s Chevy Blazer consisted of two galvanized steel pipes, about 8 inches long, packed with screws, kitchen matches, and smokeless gunpowder. ATF investigators say the explosive cylinders were sealed with metal caps. But Wright and his doctors believe the caps were plastic, based on fragments found embedded in his tailbone. Either way, one of the pipes was placed directly beneath the driver’s seat, the other somewhere behind it—in a way that would have sent shrapnel through the spine of the intended victim were it not for a steel lumbar support beam that deflected the force of the blast. A mason jar filled with flammable petroleum distillate and nails was placed somewhere near the pipes.

Two copper wires connected to a 9-volt battery detonated the device. One wire lay on the driver’s-side floorboard. The other was affixed to the underside of the floor mat, which was propped up by a wooden kitchen match, so that the two wires would make a connection when someone stepped into the car. Investigators say the wires were the same type as were found in Scott’s basement, bearing cut marks that forensic analysts say were made by the same tool. Authorities also say the match used to prop up the floor mat was the same type found in the back of Wright’s Infiniti SUV, in a box with one fingerprint on it—Scott’s. Wright told police that he regularly let Scott borrow his car, and he wonders if the matches might have been put there in an attempt to frame Wright had their father been killed.

The entire Sigmund family, exes included, knew that Donald’s fourth wife, Sara, and her two children were relocating to D.C. that weekend. (They had continued to live in the Boston area for the first three months of the marriage.) An electrician was supposed to meet Donald at his new Georgetown townhouse to install an ice maker, but the delivery of the machine to his office was late. So Donald asked Wright if he could wait on the ice maker while he went ahead to meet the electrician.

“Do you think you can handle it by yourself?” Donald asked.

“Probably. How heavy is it?”

“About 80 pounds.”

“Eighty pounds? Yeah, no problem.”

IN THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH OF THE EXPLOSION, as Wright clung to life, his family began searching for answers. Scott was supposed to take a lie detector test on July 15, an appointment that seemed routine enough to those who loved him. That morning, Scott woke up early and put on a tie.

As his wife prepared breakfast for their two boys, he told her he had a seminar to go to and he had rescheduled his meeting with the police for later in the afternoon.

He never came home. At 10 p.m. Bradey called Scott’s boss at Motivano (she says by luck she found his home number) to ask if he knew where Scott was. That’s when she learned that her husband had been laid off more than six months before.

Wright, like the rest of the family initially, didn’t know what to make of Scott’s vanishing act. Was he involved? Or could he have been a victim of the same guy who tried to blow up Dad?

Five days after Scott’s disappearance, Bradey’s 1990 BMW was found abandoned at the Vienna Metro station, a suburban stop in Fairfax, Virginia, at the end of the Metro line. He left a handwritten note in the driver’s seat addressed to his wife.

“I am sorry for the actions I am about to undertake and hope that someday you will be able to forgive me,” it read. “I do this not because I had any involvement with Wright and Dad, but I now know that this investigation will unravel the lie that my life has been for so long.” The note concluded with a request that his body be cremated when it was found, according to the ATF’s affidavit.

“I didn’t really think Scott could have committed suicide,” Wright says. “It’s just not something he would do. Of course—”

Claire began keeping an almost daily journal chronicling her 11 weeks with Wright at the Washington Hospital Center. She wrote about his 16 skin graft surgeries (eight in the first week) and her spending three hours every morning changing the dressings on his wounds and then three hours doing it again every night.

She posted the journal on a web site set up by her husband Troy Phillips’ Dallas law firm, Glast, Phillips & Murray. At first it was a matter of practicality. Claire was receiving more than 100 e-mails and phone calls each day. It seemed the best way to keep concerned friends and family updated on Wright’s condition. But over the passing weeks and months, it would evolve into a book-length narrative—not just about Wright’s medical battles, but about what it’s like for a family to be thrust into its own Greek tragedy, one that forced them to deal with medical, legal, and psycho-spiritual issues previously beyond their ken.

A few entries expressed frustrations with Donald. She complained when he took off to Nantucket during one of Wright’s surgeries and detailed an argument he had with Wright about Scott’s involvement. On October 5, the day a grand jury issued an arrest warrant for Scott, Claire’s entry read: “Wright’s dad dropped by for a moment to discuss this latest news. Unfortunately, Wright had a tremendous falling out with this father tonight during the conversation due to his father’s continual denial … that Scott could have anything to do with the bombing, as well as his father’s denial over the seriousness of Wright’s injuries. It is very sad and disappointing for Wright that his dad’s seeming need to avoid facing the reality of this horror has also seemed to cause him to avoid participating in Wright’s daily care and recovery. … Wright is naturally beginning to get angry about his being in this condition because of Scott’s seeming hate for his father, and being an innocent victim of something that had nothing to do with Wright or his relationships.”

“You look just like your father,” a family friend said to Scott. “Oh, I’m not the one,”Other relationships felt the strain, too. Claire wrote in her journal that she called Gwendolyn, Scott’s mother, once a week to keep her abreast of what was going on. But with Scott still missing and his guilt becoming a foregone conclusion, Gwendolyn apparently soured. “When I called Gwen,” Claire wrote, “she told me that she didn’t care about my ’bombed and burned child’ and that my son was ’a publicity monger who was just trying to get sympathy’ and that ’her son had nothing to do with my son’s injuries and that we could go to hell.’” (Gwendolyn Sigmund could not be reached for comment.)

Meanwhile, the search for Scott did not seem to be going smoothly. A jurisdictional confusion led to people at the Friendship Heights office building not being questioned until late August. Wanted posters for Scott were not printed until September. By that time the D.C. sniper was on the loose, so Claire figured their case had become even less of a priority. “I had told them he was probably off in the Northwest somewhere fly-fishing,” she says, “and if they put up flyers in every fly shop in the area—there can’t be that many—someone would eventually recognize him.”

Finally, in early September, authorities suggested the family contact John Walsh at America’s Most Wanted. Claire asked in her journal, “What has this world come to?” But, desperate for answers, she and the rest of the immediately involved family—including Wright, Donald, and Scott’s soon-to-be-ex-wife Bradey—sat down with producers for the television show and told them everything they knew.

Wright and Claire returned to Dallas in October, but his suffering was far from over. He went to Parkland Hospital for another skin graft, and then for a post-operative procedure in a room called “The Tank.” Claire described the experience in her journal: “They raised the side back up and started spraying water all over him while they ripped off his bandages. He was screaming like a wounded dog in pain … Then they started pulling out staples from his groin which had been cut about six inches from his scrotum to his anus and a three-inch flap had been inserted and hand-stitched and stapled. The process went on and on and then they showed me how to do the dressings, which basically consisted of sticking a rag saturated with antibiotic ointment inside his crack to keep it separated and making some homemade underpants out of white fishnet to keep the rag in place.”

The Sigmund’s episode of America’s Most Wanted aired November 9, less than a week after Bradey filed for divorce. (The show was pre-empted by baseball playoffs and the World Series throughout October.) Wright didn’t want to watch it. “I just didn’t really feel like it,” he says. “It wasn’t really a happy moment I wanted to relive.” Instead he went out for Mexican food at Mia’s with some friends who had driven up from Austin to see him.

Likewise, Claire wasn’t sure if she was going to watch. But she did, alone in her bedroom. The next morning, she got a call at 7:30 from the ATF. She woke up Wright an hour later. “Good news,” she said. “They found Scotty.”

Scott had taken a train to Oregon, then got on a bus to Great Falls, Montana. When the bus broke down in Missoula, he decided to hide in the college town of 65,000, remote enough to get away from it all, large enough to disappear in a crowd. He went by the alias Paul Nott, a policyholder with his dad’s firm who had died two years earlier. He spent a few days on the outskirts of a lakeside camp, then rented a room for $250 a month in a single-story home in a quiet residential area. Scott got a job as a desk clerk at the Missoula Comfort Inn. He told co-workers that his wife and children had been killed in a drunk-driving accident. “He said every morning he would get up and know they were looking down from above, and that would give him the strength to go on,” his boss at the Comfort Inn would later say.

Scott apparently saw America’s Most Wanted and at midnight walked into the Missoula Police Department. He had lost about 50 of his 240 pounds and was sporting a thick beard.

“I think there’s a warrant for my arrest,” he said. Police looked him up on the America’s Most Wanted web site to confirm his identity, and sure enough he was wanted by the feds. He didn’t contest extradition and about a week later was back in D.C. to face seven federal charges—including interstate transportation of an explosive device, mayhem, malicious disfigurement, and attempted murder—and a potential sentence of 100 years in prison.

Despite his initial reluctance to believe his son could be the bomber, Donald now admits, “I have no evidence to believe it wasn’t him. … I intend to have no relationship with my son. We’re just going to let the judicial system proceed.” At a detention hearing, represented by a public defender, Scott pleaded not guilty to all charges. (Scott Sigmund declined an interview with D Magazine, and his court-appointed attorney, David Bos, did not return phone calls or e-mails.)

Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeanne Hauch told the court that Scott had incriminated himself in Missoula, telling the arresting officers, “I tried to kill my father,” and that he had used an explosive device to do it. However, Missoula Lt. Jim Neumayer told D Magazine, “I don’t believe that he did [make a spontaneous confession]. He didn’t give us a statement at all, other than to say who he was and that he had a warrant.” The prosecutors also contended that Scott’s motive for planting the bomb was financial—hoping to cash in on the supposed $300,000 inheritance he mentioned to his wife. But that scenario doesn’t make sense to Wright and others in the family. Most, if not all, of the Sigmund children’s inheritance was in life insurance. And Scott, having worked in the insurance business, would have known perfectly well that he wouldn’t get any money without a full investigation that would track down the slightest scent of wrongdoing by any beneficiary.

Nevertheless, Scott was denied bail, and as of press time his trial is scheduled to begin in March.

WRIGHT SIGMUND HAS HAD RECURRING nightmares. In the D.C. hospital, doped up on painkillers, he imagined that hamburgers were being grilled beneath him, or that the nurses were brewing up something called “spartaram” to kill him. Those hallucinations have subsided, but one particularly disturbing dream still won’t go away. In it, he and his mother are in a nondescript car. Scott is underneath it on a mechanic’s dolly, grabbing Wright by the ankle as he tinkers with the chassis and loads it with bomb material. No matter how hard Wright tries, no matter how much stronger than Scott he always was, Wright can’t get away. He wakes up in a frightened sweat. To make matters worse, he sometimes wakes up covered in fecal matter, as too much movement in his sleep can cause the colostomy bag attached to his left side to leak. The nighttime uneasiness, combined with an ever-changing regimen of medications—Wright takes anywhere from 16 to 24 pills a day—has left Wright with a bad case of insomnia and a general feeling of fatigue throughout his days.

WRIGHT SIGMUND HAS HAD RECURRING nightmares. In the D.C. hospital, doped up on painkillers, he imagined that hamburgers were being grilled beneath him, or that the nurses were brewing up something called “spartaram” to kill him. Those hallucinations have subsided, but one particularly disturbing dream still won’t go away. In it, he and his mother are in a nondescript car. Scott is underneath it on a mechanic’s dolly, grabbing Wright by the ankle as he tinkers with the chassis and loads it with bomb material. No matter how hard Wright tries, no matter how much stronger than Scott he always was, Wright can’t get away. He wakes up in a frightened sweat. To make matters worse, he sometimes wakes up covered in fecal matter, as too much movement in his sleep can cause the colostomy bag attached to his left side to leak. The nighttime uneasiness, combined with an ever-changing regimen of medications—Wright takes anywhere from 16 to 24 pills a day—has left Wright with a bad case of insomnia and a general feeling of fatigue throughout his days.

The physical wounds, in some ways, are almost easier to deal with than the psychological trauma. To date, Wright has had 17 surgeries, mostly skin grafts and what are known as “release” surgeries, basically cutting scar tissue so that it doesn’t grow awkwardly.

“People forget what happens to the injured,” Claire says. “When you see something on the news about a Palestinian bomber where you hear three dead and 30 injured, you only think about the three dead as a measure of the tragedy. I never thought about the injured—because they’re alive, right? But being injured is only the start of the horrors to come. It’s life-altering, and you have to live with the pain every day.”

This past fall and winter, instead of studying philosophy and business in school, Wright did full-time rehab. Five days a week, three hours a day, he went through grueling physical therapy at UT Southwestern Medical Center. After some basic working out to improve strength, stamina, and flexibility—made especially difficult by the fact that scar tissue doesn’t stretch much and doesn’t sweat at all—he’d undergo the most unpleasant experience of having his wounds massaged.

In early December, his right leg and what’s left of his buttocks looked like a raw side of beef. As a physical therapist rubbed ointment on the scars, Wright bit down on a toothpick and moaned throughout the process. “I can almost tie my shoes now,” he said at the time, grimacing.

To Wright’s own surprise, one of the most helpful parts of his recovery was his work with Dr. Harold Crasilneck, a pain hypnotist. Crasilneck is a clinical professor of anesthesiology at the University of Texas Health Science Center, and he’s one of the world’s leading authorities on using hypnosis to help burn victims—a concept

he pioneered in 1955. Students from St. Mark’s volunteered to drive Wright to Crasilneck’s Medical City office, where he plants suggestions about feeling less pain in Wright’s unconscious mind.

During one recent session, with Wright in a deep trance, Crasilneck asked him what he was feeling. “I’ve been thinking about Scott more than anything,” he said, straining to get words out. “Hopefully everything goes all right, he’ll go to jail. I still can’t believe it happened. I definitely loved him. He was my brother. He hurt the family so much. It’s still really hard to fathom.”

In December, doctors cleared Wright to return to W&L. He’ll have to return to Dallas in February so doctors can reassess his situation. As of now, he’ll undergo surgery in June to reverse the colostomy. By summer 2004 his scars should be conditioned enough that a plastic surgeon can reconstruct his buttocks. Doctors aren’t sure yet, but they might use muscle from his abdomen, then cut a layer of fat from his thigh, fold it over backward, then graft skin on top of the whole thing. If so, when Wright sits, he’ll feel like he’s sitting on the top of his leg for a few years, until his brain reprograms the nerves.

“I know God saved my life for something,” Wright says. “I’ve just got to figure out what that is and what I need to do. Until then, I’m just going to appreciate the small things and happy moments in life.”

In the weeks before returning to school, Wright attended two wrestling tournaments at St. Mark’s. There he watched the students do what he no longer could. But far from depressing, it was a refreshing retreat from home and hospitals.

Standing with the team behind the bench, he paid particular attention to a talented 135-pound senior. The kid was an eighth-grader when Wright was team captain working toward his state championship. When the whistle blew, Wright was barking out moves like an assistant coach: “Double-leg takedown! Fake drag-clutch!” He was fully into the fight. Someone else’s fight.

If only for a few minutes, he was able to forget his own daily ordeal—living in a world where pain is constant, justice isn’t simple, and a sense of family has been forever lost.

By Dan Michalski