The two met in 1998, when Courtroom Sciences Inc., the litigation consulting firm Dr. Phil co-founded in Irving in 1990, helped Oprah in a high-profile $10 million lawsuit brought by Texas cattlemen after she announced on her show that she was swearing off beef. According to Dr. Phil, she was prepared to settle out of court, but he convinced her to stand up for what she believed in. The two became good friends, and Oprah invited him to appear on her show, a gesture tantamount to the gift bestowed on Midas.

Soon, everything Dr. Phil touched would turn to gold: three books on the New York Times bestseller list; a weekly appearance on Oprah; a regular advice column in O, The Oprah Magazine; and a show of his own due this fall. Dr. Phil’s no-nonsense blend of warmth and stern advice are in high demand, making him the latest guru to be embraced by a country increasingly bent on self-improvement.

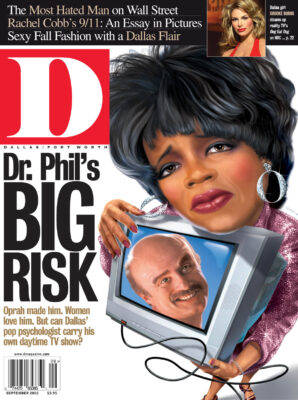

Oprah has done everything to ensure Dr. Phil’s success, from pronouncing him “one of the smartest men in the world” and the man she’d choose if she ever needed a shrink to throwing the immense power of her company, Harpo Productions, behind his new show. But will Dr. Phil’s star continue to rise when he’s alone in front of the camera, no longer seated at the right hand of Oprah? Does this man really have something special to offer that separates his message from the rest? And if Dr. Phil can’t survive the daytime talk-show wars, is it his fault or ours?

If America is a country with a seemingly limitless thirst for easy answers, then Dr. Phil is the soda jerk du jour. Reductionism is his syrup—he seems to have a concise, utterly self-assured directive for every relationship, career, and family problem in the book. Whether or not complex interpersonal and psychological problems are best handled by such pat answers, clear absolutes seem to define Dr. Phil’s product. He turns his back on complexity in a casual, shoulder-shrugging manner that makes willful simplicity look almost heroic. Like a simpleton wandering up and pointing out that the emperor has no clothes, he writes off complicated psychological analysis as a load of hooey. Forget the underlying causes of dysfunction, he tells us. Forget blaming your parents for your troubles. Whining and playing the victim won’t get you anywhere. Nevermind that we can get this common wisdom from any co-worker or grocery-store clerk. Dr. Phil claims personal credit for the string of clichés that makes up his message: the way to have a happy life and a good relationship is to face yourself and your faults and change the behaviors that make you unhappy.

And unlike most naysayers who rail against the tender-pawed advice of therapists, Dr. Phil is at least somewhat qualified to point out psychology’s bad habits. He was a clinical psychologist for 10 years, sharing a practice with his father in Wichita Falls. But he’s humble about his experiences with therapy, describing himself as “probably the worst marital therapist in the history of the world.” This self-deprecation is something of a calling card for Dr. Phil. He likes to say that he’s made every mistake in the book, deftly transforming his former failings into yet more reasons we can relate to him and trust him.

In his book Relationship Rescue, Dr. Phil pinpoints the exact day he knew he had to leave his life as a therapist behind. A married couple came to see him, to save their relationship. “I started talking, giving Larry and Carol the same platitudes, the same conventional wisdom, that I and every other therapist had been doling out for years. … As I sat there, I asked myself, ’Has anybody noticed over the last 50 years that this crap doesn’t work?’ … That day with Carol and Larry was a turning point in my life. … I resolved right then and there that I was going to get real about why relationships were failing in America and what needed to be done to turn the tide.” With just a few sweeping statements, Dr. Phil has gone from disillusioned drone to heroic rebel, the lone voice in the wilderness willing to speak out against an outdated approach to human relations.

If anyone can do it, or rather, if anyone can make you think he can do it, Dr. Phil is the man. He has an uncanny ability to hit all of his major points without coming across as a huckster. He covers all of the basics in each public appearance: America is in trouble, no one is teaching us how to handle the challenges we face in this world, and Dr. Phil is here to save the day by “telling us the truth” and forcing us to “get real.” He pounds home the same message in the introductions to his books, in print interviews, and in public appearances, such as the one on The Rosie O’Donnell Show. He is so focused on his message, and such a clear communicator, that it’s tough to see the man on TV without remembering his personality and quickly grasping what he stands for. He stands for getting real; he stands for the truth. He crosses his legs, cocks his head, and tells us it’s time for a wake-up call, and we sit up and listen. But when it comes to specific directions, Dr. Phil basically encourages people to communicate how they feel and what they want from each other—exactly the kind of empty advice he lambastes repeatedly in his books.

Dr. Phil may well be the Chauncey Gardiner of the self-improvement circuit. He gets by on his courage of conviction and a distinctly American charm. His mantras have a simple, macho feel to them, combining down-to-earth small talk between good old boys with the tough talk of football coaches and the jocular slang of beer commercials. To a country swimming in distinctly feminine, New Age flavors of self-help, Dr. Phil’s red-blooded American male delivery has pulled self-improvement out of the closet. “You either get it or you don’t,” he tells us, sounding like a hardened old bartender who’s seen it all. “If it’s unfair, it’s unfair, but you still have to deal with it.” And he repeats his ability to “tell it like it is” so often that those words are inevitably used in every publication and bit of press that bears his name. Pandering and mincing words isn’t Dr. Phil’s style. Telling it like it is—that’s Dr. Phil’s style. That’s what he does, that’s what he’s all about. (Cue that shout of “Tell it like it is, brother!” from the Good Times laugh track.)

The substance of his opinions isn’t groundbreaking or even all that original, but his style and charisma sell every word. With the likability and frank manner of a trusted friend, Dr. Phil seems to pull off the impossible week after week, pointing out the obvious faults and flaws of individuals and couples on Oprah’s show, but without coming across as unforgiving, punishing, or egotistical. Dr. Laura he is not. Ultimately, most of the advice he gives on the show amounts to colloquial scoldings that could just as easily have sprung from the mouths of the audience on Ricki Lake. “Time to face the facts, buddy,” he says solemnly. “Tell the truth, girl.” And Oprah’s guests do just that, as so many of them are reduced to tears that weeping has become almost a trademark of his work. But Dr. Phil stays above it all. He’s the tough guy, the coach shouting encouragement from the sidelines without getting so much as a drop of mud on his tie.

No one gives the myth of Dr. Phil more resonance than Oprah Winfrey, cast as she is in a supporting role to Dr. Phil’s lead. Of course the story is sugarcoated with gratefulness and humility—having sprung from the head of Zeus in just four years, Dr. Phil wisely paints Oprah in the most intimate terms. He says that Oprah, who’s widely considered one of the most powerful people in the entertainment industry, is his mentor, “one of [his] closest and dearest friends,” the sister he “never wanted” (he has three sisters already), and his business partner. According to Dr. Phil, when he met Oprah, he gave her a “wake-up call.” This oft-repeated tale casts the all-powerful and all-seeing Oprah in a vulnerable light, all womanly emotion and fear in the face of the impending lawsuit. But our story ends happily, with Dr. Phil, the masculine, no-nonsense hero and savior, riding in on a white horse to save Oprah from certain peril. He has also said that Oprah has had “every psychiatrist and expert in the world on her show, and none of them made as much sense as I did.” When statements like these are taken with the evangelical rhetoric Dr. Phil employs when promoting his new show, he sometimes seems poised to upstage his friend and “sister,” subtly casting himself above Oprah on the marquee, as if, ultimately, she has merely provided a stage for him to spread his good word. Still, he recognizes the formidable power Oprah brings to his brand, and lest you think he’s striking out on his own, he offers that he and Oprah have been working “shoulder to shoulder, elbow to elbow” on his new show “from the get-go.”

Friends and critics alike agree that Dr. Phil is incredibly smart and talented, but his greatest gift of all might just be his gift of spin. He fields questions about his upcoming show with gracefully inexact language. When asked by Entertainment Tonight to describe his show, Dr. Phil says only that it’s “exciting,” that it represents “a unique approach to television,” and that there will be “things that people have never seen before on the air.” While these phrases could refer to any show from American Idol to Celebrity Fear Factor, Dr. Phil maintains total control over how much information he’s willing to share. He manages to make vague answers seem detailed, to make elusiveness feel like directness. How long has Dr. Phil been working on this concept for a show? “For a good while, but it’s something you work on until it feels right.” What types of things will we see on the show? “What you are not going to see is me interviewing celebrities for celebrities’ sake. I’m not interested in that sort of thing.” Okay, but what will we see? “We are going to give a wake-up call to America in some areas that [people] maybe are a little touchy to talk about sometimes.” Here is our outspoken rebel again, boldly daring to go where no man has gone before. With obtuse, indirect, yet romantic answers like these, Dr. Phil reveals absolutely nothing but still manages to come across as a friendly, capable guy who’s in this not for the glory or the money but for the greater good of the American people. Even when he’s running on fumes, he convinces us that he’s winning the race.

But some of Dr. Phil’s charm on The Oprah Winfrey Show may be lost when he’s alone on our TV screen and doesn’t get to play off Oprah. One is an extension of the other but not necessarily a substitute. There’s something disarming about the way Dr. Phil and Oprah interact onscreen. The two do come off like talented siblings, gently teasing each other while praising each other’s wisdom at every turn. While Dr. Phil’s charm is indisputable, is his personality dynamic enough, fun enough, and vulnerable enough to ensure the popularity of a daily talk show? As a long list of demi-celebrities have learned the hard way, launching a new talk show is a feat on par with running for president, particularly this year, when ratings for talk shows—even those as popular as Rosie’s and Oprah’s—have plummeted.

A lot depends on just how creative and unique the format of Dr. Phil’s show proves to be. There’s certainly no lack of brains and talent behind the project, but while Dr. Phil is more knowable and likable than Dr. Laura, he’s certainly no Oprah, either, a woman who’s shared her victories and failures with her audience for years, to the point where millions of viewers trust her more than they do members of their own family. Dr. Phil, by contrast, is more father to the masses than sister, more coach than fellow team member, and while he dabbles in self-deprecation and casually alludes to past failures, he is far too political to approach his own past with as much honesty as a daytime audience typically demands. If Dr. Phil wants us to eat his cooking every day, he’d better be prepared to let us into his kitchen. Ultimately, the very traits that make Dr. Phil a defined product—simplicity, frankness, and repetition—may be his greatest obstacles to success on a larger scale.

Still, if Oprah is as involved as Dr. Phil suggests, success may be inevitable. This is a woman who would mention a book and two days later it would become a bestseller. It’s hard to imagine any project of hers failing. And Dr. Phil, poised on the brink of fame in his own right, is playing his role brilliantly. Despite every grandiose statement about his show (“I want to create appointment television for people who have a mission, a purpose in their lives”), he’s still dishing up more boyish humility than Gomer Pyle. Yes, he is “overwhelmed” by his popularity and considers it “a privilege.” “I didn’t have any idea that I was going to be in this many people’s living rooms on a regular basis. But you know what? Necessity is the mother of invention. As a society, in many respects, we are spinning out of control.” Yes, Dr. Phil will admit that he’s astonished that he has become a household name, but he’s only become so popular because we need him so badly.

But we do like Dr. Phil; we like him in spite of ourselves. Although it’s easy to be suspicious of another talking head touting his lucrative franchise with such self-congratulatory bravado, Dr. Phil is a comforting presence onscreen. When he smiles and chuckles and then gets all serious and solemn, we quickly forget that he’s talking about a business and not a valiant initiative to effect social change. Whether he really wants to fix us, or just wants his own cult of personality with TV ratings to match, we’d prefer to believe the former. There’s something in his relaxed but intense manner and his anecdotal style that calls to mind fellow Dallasite H. Ross Perot, a man whose charm and intelligence charged the ’92 presidential election with an electric sense of possibility. Surely Dr. Phil was conjuring Perot’s “They’re all nuts” approach when he told ET, “I think people are ready to hear the truth. I think that they are tired of people blowing smoke, telling them what they want to hear and giving them a lot of buzzwords.”

Like Perot, who managed to come off as a simple, down-to-earth country boy instead of a skilled businessman and billionaire, Dr. Phil’s pompous horn-tooting hardly even registers. All he wants, after all, is to help the common folk of America find a little bit more happiness. Just as Perot promised that every vote for him sent a message that people are fed up with the dirty politics and empty promises of Washington, so Dr. Phil tells us that if he gets good ratings, it will be a sign that the simple folk of America are hungry for the truth.

Until his show premieres, Dr. Phil, for one, is keeping the faith: “If they believe that I know what I’m doing and that I’ll tell them the truth, I think they are going to tune in and make it a part of their day.”

Heather Havrilesky is a freelance writer who lives in LA and watches her fair share of daytime TV.

Author