The second presentation went smoothly—no mention of mudpacks or hair gel—until she finished inspecting the glass key.

“Very nice,” she said. “What does this get us?”

“Pardon me?” I said.

“I say, what does this key get for People’s Republic?”

“Elvis,” whispered Dace. “Let’s git.”

In stressful moments, I fall back on the familiar.

“Well, ma’am, I suppose when you come to Dallas, it’ll get you the biggest and tastiest chicken-fried steak you ever saw.”

There was a long silence. I don’t like to brag, but I pretty much invented chicken-fried steak in Texas, the same way Doak Walker invented football and Candy Barr invented tassels. Oddly, our host was unimpressed. I don’t know if there was trouble with the translation of “chicken-fried,” or if she was looking for something a bit more tangible in hard currency terms, but she said, “Good day, gentlemen,” and just like that, we were out on the street, our one shot at international diplomacy a washout.

Whenever I’m in doubt about what to do next, I like to stir things up, make something happen. After that embarrassing episode, I was ready for Kitchen Invasion Number 2. Number 1 had taken place the day before. We’d heard about a successful restaurant in Saigon called Indochine, and we’d barged in, slapped 500,000 Vietnamese dong on the counter, and said, “We’re here to work.”

Some people might have phoned ahead and said, “We’re a couple of restaurant owners from the United States, and we’d like to see how you prepare food in your kitchen. Could we make an appointment?” Not my style. I always jump in with both boots. You’d be surprised how often it works. I met two of my wives and three business partners by just blurting out what I wanted before I’d known them for two minutes. In 1970, I kept nagging this guy at the Knox Street Pub, telling him over and over how much I wanted to open up a bar and serve hamburgers and meet girls, even though I had no money and no experience and no prospects of either. That guy was Phil Cobb, and six months later we opened J. Alfred’s, the forerunner to the Black-Eyed Pea.

The manager at Indochine looked down at the stack of bills. Five hundred thousand dong might sound like a lot of dough, but with 15,000 dong to the dollar, it was only 30 bucks. Still, money speaks just as loud in Saigon as it does in Salado, and the manager, laughing, showed us to his small, extremely clean kitchen. We strapped aprons over our black shirts and slacks, and we watched him work for a minute.

“You’re pretty slick with that knife,” I said.

Nguyen looked us up and down, a pair of round-eye tourists lounging around his kitchen.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“Texas.”

“Ah, America.” Nguyen wagged his knife at me. This was gonna be it: the lecture about the war I’d been expecting since we landed, about how his relatives had been lost in a nameless battle or his hometown burned to the ground by William Calley. Instead he held his knife out toward us, flat, a couple of pieces of sushi on the blade, and said, “America is what we need more of around here.”

“Really?” Dace said. “I thought you liked the Russians.”

He shook his head.

“Russians had plenty brains. They bring too much gray cement and no money. Everything go to pieces when they here.”

I told him I ran some restaurants in the United States.

“Ah, you restaurant man?” He hollered out to a couple of other kitchen guys, then turned back to me. “What you want to cook, Restaurant Man?”

I looked at Dace, who, I’m proud to say, blurted out the very phrase that Elvis said to his chef when the two were alone in the Graceland kitchen: “Let’s fry something.”

Nguyen nodded and motioned for us to begin.

“You got flour?” said Dace. A tin of rice flour appeared. “Salt? Pepper? Pork drippings? What kind of meat you got?”

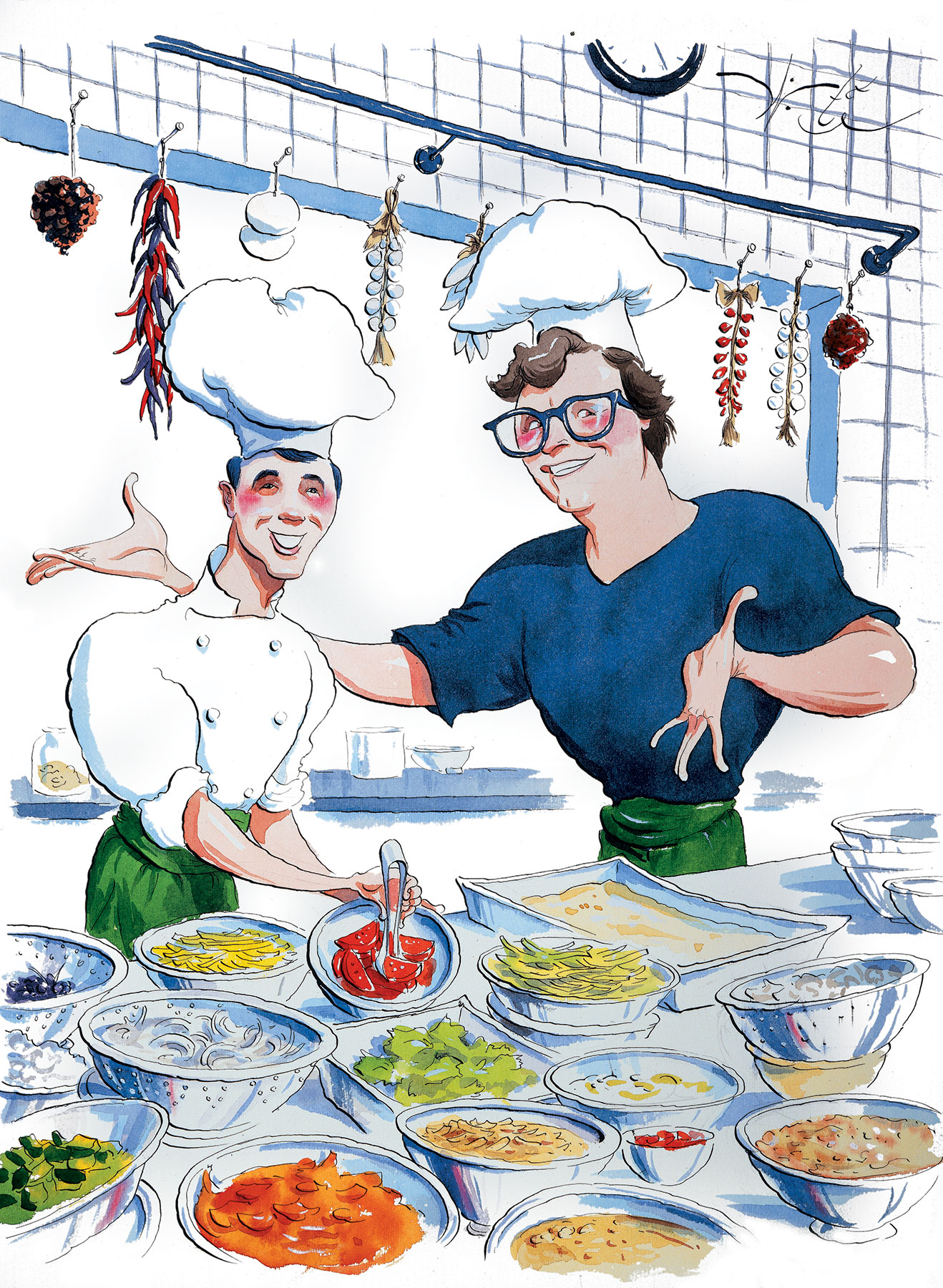

Nguyen offered us fish, pork, and chicken. The two Texas invaders set to work, and soon we were introducing our new friends to chicken-fried sea bass.

Meanwhile the kitchen kept buzzing around us with the regular orders. Soups were spinning off one line, grilled fish wraps and duck rolls from another. Appetizers and main dishes and homemade sauces, all for different tables, going out on one jammed tray, the waiters keeping track of orders in their heads like bookies. There’s very little talking, unlike an American kitchen, where the shouts and insults are as thick as gravy. These were mostly men, all ages, everyone moving with a purpose. No dishwashers sneaking out back for a smoke. If there’s one thing I learned about Vietnam, it’s that the people work hard. I’ve always prided myself on working hard (when I asked my older son, Gene Jr., if he wanted to come along on this trip, he said, “Are you nuts? You always told me I’d go to hell if I ever took two weeks off.”), but these guys put me in the shade. I had to wonder, at a dollar or two a day in wages, how do they motivate these guys? Are they all hoping to get out of here, like the taxi driver who passed me his high school photo and a business card along with my change and said, “I work for you in America, yes? I very good garden man, I drive your car, I clean your house. You take me there now, okay?” Or is doing a good job a way of fighting the craziness and poverty out in the streets? As a boss, I’ve motivated people by threats and by raises, by paying their rent, by impersonating their parole officer, by sending a telegram from South Dakota saying, “We’ll be welcoming you soon unless you get your act together down in Texas.”On one wall in the Vietnamese kitchen was a picture of Buddha, calm as a Marfa sunset; on the other, the un-Buddha, Bill Clinton, grinning like a kid who’s skipped school.

The chicken-fried sea bass turned out pretty good, and we ended up feeding a few French tourists and expatriate Americans with our creations. The manager told us to come back any time.

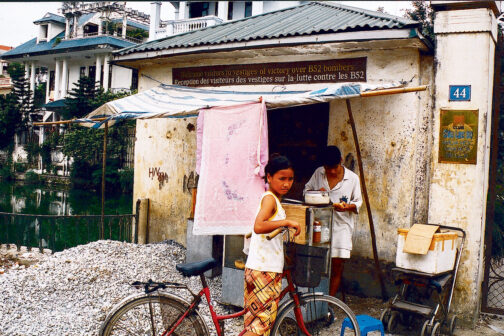

But now, freed from the clutches of the Reunification Palace, we wanted to try something a little more exotic.

“I know that man,” I said. “Me know Bill.”

Luong, the cook, was impressed. Clinton is a hero here for lifting the trade embargo in 1994 and for being against the Vietnamese war in general. I figured I could stretch the fact that I met him a couple of times into knowing him, if it would smooth our kitchen intrusion.

Luong said he had beef and chicken, but Dace and I were set on exotic. What else? A guy came back from the freezer and said there was plenty of monkey. He’d also found some dog (you knew that was coming) and thought there was just enough left for one serving of snake. Cobra, I think it was.

“Let’s start with the monkey,” I said.

We called again for flour. Again rice flour appeared. No regular flour, no explanation. The meat from the monkey was delivered in strips that looked as tough as a worn-out shammy.

“You got a hammer?” said Dace. “Put a cloth over that monkey meat and beat it until it screams.”