Mama Street used to tell me I was as vain as a TV preacher on Easter Sunday. Hair flowing down to my shoulders, a T-Bird convertible with hubcaps so shiny I could see myself, three dates in a single Saturday night—I was living large. At least the kind of large the son of a Brownwood pig farmer could only dream of. But one day, an unexpected change took place. If it hadn’t, I might still be a bandleader, strumming “Faded Love” and “Yellow Rose of Texas” for geezers at the Longhorn Ballroom every Tuesday night. I discovered something more exciting than rock ’n’ roll, more jiggy than doing 90 down a blacktop road at midnight: I found out that normal people—people with jobs and families and checkbooks—would pay me $5.95 for a piece of chicken-fried steak and two vegetables, and they’d call it a bargain. Add a beer, an iced tea, or a piece of apple pie and you got an $8 meal. My cost was $2.50, $3 tops; the rest was profit. Praise the Lord, brother. I saw the light.

Now I’m 62, and my hair hasn’t seen my shoulders since Troy Aikman was at Oklahoma. The only convertibles I get into nowadays are debenture bonds. I’m happily married (for the fourth time) and the proud father of six grinning children. But my mama and the Good Lord know I’m still vain.

I heard a knock at my door. Not the soft rap of room service but a hard bap-bap. That would be my number two son, Dace. I’d brought him along to Saigon to sample some authentic Vietnamese food and do a little research for a restaurant idea I’ve been kicking around. But more important, I was hoping to close the distance I’d felt between us for years.

When Dace came along in ’65, changing diapers was way, way down on my priority list. By the time he was old enough to play catch, I was too busy flogging shock absorbers in Chicago or serving liquor at J. Alfred’s, my first Dallas bar, to pick up a ball and bat. Now he was 37 years old, a husband and father and successful restaurateur in his own right, and I was hoping it wasn’t too late for a little father-son bonding. Maybe we could have some talks like Big Bush and Little Bush at Kennebunkport.

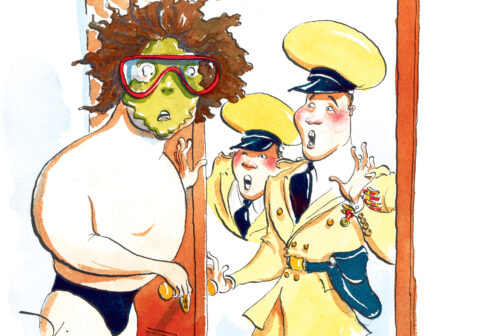

And yet I couldn’t have the boy thinking his old man had mellowed. I squished my gooped-up hair into a fright wig—kind of like Alfalfa on crack—yanked my underwear up into a wedgie, and threw on a pair of windsurfing shades. I didn’t mean any harm. I just wanted to send him stumbling backward into a maid’s trolley. I bent down, eye-level with the doorknob, eased open the door, and said in my best Wicked Witch voice, “Just in time, doctor.”

The first thing I noticed, looking floor-ward from my hunchback pose, was the shoes—Jack Webbs, shiny and black. A disturbing sight. My son Dace is a Republican, but he’s no Donald Rumsfeld. He wouldn’t wear Jack Webbs on a bet. The second thing—more disturbing—was that there were four shoes in all, plus two pairs of creased khaki pants, the kind worn proudly by Boy Scouts and soldiers the world over and, in this case, by a pair of Communist “servants of the people,” i.e., cops. I slammed the door shut. Another bap-bap. I straightened up, took off my shades, and peeked out.

“Yes?” I tried to smile, but all the watercress mud seemed to have dried at once, and the best I could manage was a Bozo-like grimace.

“How many tourists in there?” he said.

“Just me,” I said. When I flung open the door and stepped into view, they got the whole picture—bare belly, watercress, and all.

For a moment I thought they might turn and run. The shorter one jumped back into the taller one, and both of them looked stunned, like their favorite dog had just asked for a smoke. It was 91 degrees outside and dark spots of sweat were popping up on their uniforms. They seemed baffled by the magnitude of American depravity they’d uncovered. The capitalistic system was known to produce class warfare and soulless factories and cigar-chomping plutocrats—but this? What the hell was this?

I should mention that this was no Motel 6 we were in. The Caravelle Hotel in the heart of Saigon is super-luxe, the kind of place where chefs waltz into your room to make your lunch. I’ve stayed in the best—the Four Seasons on Maui, the Lanesborough in London—and this was hands-down my best room ever. And it cost less than 200 bucks a night. Finally the taller one couldn’t take any more.

“We here for Mistah Street, Texas restaurant man,” he said.

I suppose I could have pretended I was just room-sitting, awaiting the return of the dignified and respectable Mr. Street, but I figured that if the law thought a foreigner was both depraved and uncooperative, things could turn ugly. While we’d been staring at each other, the mud had sucked my skin dry. I flexed my entire face and said, “That’s me.”

Instantly they relaxed. The lunatic they’d stumbled onto was also the lunatic they were after. The tall one pushed the other guy aside and stepped toward me.

“You get dress now. Vice chairman of People’s Party no like to wait.”

Vice chairman? I’d only been in the country a couple of days, but I already knew the vice chairman was a dragon lady, a Janet Reno-type who took no nonsense. But what had I done? I’d bought a couple of fake Rolexes, but so what? The entire economy is based on fake Rolexes. I’d made a few dog-eating references to my wife back home. Was the telephone bugged?The Vietnamese police seemed baffled by the magnitude of American depravity they had uncovered.

And then I thought I got the joke. My nemesis, my Lex Luthor, the lovely and talented Shannon Wynne, must have set this whole thing up.

For the last 30 years, we’ve played practical jokes on each other all over the world. Strange foods and drinks have been delivered to our tables, odd people have accosted us in unlikely locales—all in pursuit of a laugh. For the first time ever, I was longing for the sound of Wynne’s high-pitched cackle to break out from behind a potted plant. But there was no cackle. Instead, we heard a voice at the far end of the hall:

“Elvis! Elvis!”

It was Dace, my son, being shoved along by a pair of deputies, both with batons on their belts. “Elvis” was the code word we’d agreed on for whenever there was trouble.

Dace lurched into view and then stopped, his face twisted by shock.

He said, “Who did this to you?” He shielded his lips so only I could see. “Was it hookers? Good Lord, Dad. Never let ’em make the drinks.”

“Easy, boy,” I said.

One of the guards pointed a foot-long piece of glass at me.

“You wrong with this key,” he said.

Now it was my turn to be shocked. It was a key, the Key to the City of Dallas that Mayor Laura Miller had entrusted to me before our trip. I’d delivered it earlier that day to a low-level dignitary in a bland Russian-era building across town.

Dace, his first trip to Asia in a shambles, his father’s instability on public display, leaned toward me and whispered, “Are we going to jail?”

The moment I’d longed for had arrived. I hitched up my underwear, sucked in most of my stomach, and said in a deep Lorne Greene voice, “I want you to know, son, that whatever happens, your dad won’t abandon you. Yes, there were times in the past when I should’ve—”

“Now we go,” said one of the guards, cutting the father-son bonding short.

“Are these guys kidding?” Dace said.

“Are you guys kidding?” I said.

“No one kid you, Mistah Texas man,” one cop said. “You wipe that happy cream off you face and come with us.”

Get the SideDish Newsletter