Five

Five

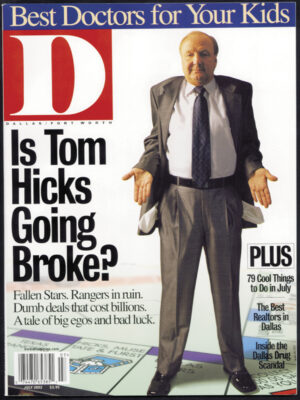

minutes into my conversation with Tom Hicks, and Dallas’ best-known

investor is warning me. Sitting in his office, filled with marble and

tasteful bronze art, he is affable and friendly—certainly not

threatening in any way—but he wants to set me straight. Hicks, 56, is a

big man with easy grace, and he’s settled comfortably in his chair on

the other side of a huge conference table. He is clearly bemused by my

line of questioning. Is the recent poor performance by Hicks’ private

equity firm—Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst—connected in any way to the

poor performance of his sports teams, the Dallas Stars and the Texas

Rangers?

“The mistake the

media and the analysts all make is trying to connect the dots,” Hicks

tells me. “The two have nothing to do with one another.”

“Except that you’re in charge of both of them,” I reply.

And so begins my

education. But while Hicks launches into his peroration, which has the

sound of something he’s had to say before, I can’t help but think that

this is a man who has made millions by connecting dots no one else

could see—and who is now losing millions. Having cast himself and his

firm so much in the public eye by becoming a team owner, he shouldn’t

be surprised to find himself under scrutiny.

On the face of it, of course, the leveraged buyout business has nothing in common with the sports business.

Nobody is suggesting

that the Stars’ failure to make the playoffs resulted from the collapse

of Hicks Muse’s telecom investments. Nor that the Rangers’ last-place

finishes in the AL West for the past two years are connected to the

failure of Hicks’ Latin American sports channel. The burst of the

Internet bubble, the recession, the meltdown of the Argentine

economy—there are distinct reasons for Hicks Muse’s problems in

different investment areas. As for the sports teams, perhaps it is

inevitable that winners eventually become losers. Except for the New

York Yankees, dynasties just don’t happen anymore.

Then again, there are

all of those dots. In the past 18 months, the general managers and

coaches of the Stars and the Rangers have been dismissed. Jim Lites,

the man supposedly running both teams, was forced out. Hicks Muse

partner Charles Tate retired in June. Partners Mike Levitt and Cesar

Baez, who were in charge, respectively, of telecom and Latin America,

left the firm earlier.

Another huge dot popped up when Hicks publicly threatened in March to pull out of the Victory project if the Palladium

proposal to use $43 million in tax increment district funds was not

approved (the deal would win approval in May). Because his only role in

the project would have been to sell his partnership portion to

Palladium, some observers saw the threat—planted in the Morning News—as

little more than a head-fake aimed at the City Council, which Hicks

himself later acknowledged in the New York Times. The episode made

Hicks look more like a petulant child than the astute and seasoned

investor he is. That impression was magnified when he called up KTCK-AM

1310 (The Ticket) to complain on the air about the station’s take on

the Victory project, rambling on about tax increment financing. At that

point, something began to sound less like petulance and more like

desperation.

In Hicks’ office, I

keep trying to connect the dots, and he keeps setting me straight. The

performances of the Stars and Rangers have nothing to do with

front-office turnover, Hicks says. The failure to develop property

around The Ballpark in Arlington and the controversy over Victory

spring from the bad real estate market and nothing else. The botched

investments by Hicks Muse are the result of bad timing. The turnover of

key personnel at Hicks Muse and the sports teams is unrelated to any

turmoil in those businesses.

But eventually the

dots line up so neatly that you don’t even need to connect them to see

where they’re headed. The line Hicks doesn’t want drawn leads right

across the conference table. And he seems to be struggling to avoid the

central question before him: is Tom Hicks’ world crumbling around him?

Or, put another way: just how many millions can a millionaire afford to

lose?

Missing the Bar

Before we get to

Hicks’ sports interests, let’s have a look at his cash-generating

machine, Hicks Muse. The fact is that the machine isn’t running well.

Its problems predate the Internet meltdown and the 9/11 market crash,

but those certainly didn’t help. The ship is righted now, Hicks says.

What he won’t acknowledge is that he still has a lot of wreckage to

deal with.

Hicks made his name

in the leveraged buyout business in the mid-1980s, when he and partner

Bobby Haas bought Dr Pepper and Seven-Up in two separate deals totaling

$646 million (the combined companies were later sold for $2.53

billion). He went on to form Hicks Muse, where he followed a

buy-and-build strategy that wasn’t universally embraced at the time.

When LBO firms first came into vogue in the 1970s and ’80s, many made

their money by breaking up companies and selling the parts. Hicks

instead bought companies that were undervalued—first in the food and

manufacturing sectors, later in media as well—and built value through

investment and sound management.

Private equity firms

like Hicks Muse (the term “leveraged buyout business” is synonymous but

lost favor in the 1990s because hostile takeovers gave it a bad

connotation) are fairly simple businesses, at their core. They

generally raise money for a fund from institutional investors to buy

stakes in companies where they see upside potential. The private equity

firm typically draws down on its commitments from investors for a

five-year period, buying and investing as it goes. Generally, the goal

is to cash out after 10 years. The private equity firm gets annual

management fees of 1 to 2 percent, usually weighted more heavily in the

first five years to “keep the lights on” while the firm hunts for

target companies. The investors get a preferential rate of return, and,

at the end of the fund’s life, they get their money back plus the

lion’s share of the profits, with the equity firm getting 20 to 30

percent. If all goes well, partners like Tom Hicks make a lot of money

on their expertise, and the investors get a higher rate of return than

with other, more conservative investments. Being successful requires

buying right and not overpaying for target companies.

The success or

failure rate of these funds is difficult to gauge, because the firms

themselves do not make return rates public and the long-term nature of

the funds allows for turnarounds after bad starts. Nobody doubts,

however, that Hicks Muse had a golden touch during the early and

mid-1990s. It certainly had a golden touch in attracting investors,

quickly becoming one of the largest private equity funds in the nation.

Its first two funds

performed well, with the right combination of food, manufacturing, and

media plays. The third fund, started in 1996, has also done fairly

well. By the late 1990s, though, the investment climate began to heat

up. Investors leaped like lemmings into high-tech, and anyone who

wanted some of their money had to jump ahead of them and pretend to be

in the lead.

With its fourth

fund, in 1998, Hicks Muse changed strategies. Out of a $4.1 billion

pool, the firm placed $1.2 billion in telecom, buying minority stakes

in public companies in a bid to become a major player.

Meanwhile, the New

Economy siren song grew more and more enticing. Venture capital firms

posted gigantic returns, and the pressure was on to match them. Hicks

Muse jumped in by borrowing $200 million and investing in several

Internet companies, with the thought of folding them into its next

general fund. At the same time, it launched a $964 million Latin

American fund with the idea of exporting U.S. media expertise to the

South American market.

As the Hicks Muse

partners went out to peddle their fifth general fund, the New Economy

turned ugly. The first to go down were the telecom investments.

Four—Teligent, ICG Communications, Viatel, and Rhythm

NetConnections—would file for bankruptcy. ICG collapsed only six months

after receiving a Hicks Muse infusion of $230 million. Analysts think

the telecom plays will be nearly a total loss for the firm.

Then came last year’s

meltdown of the Argentine economy, which hit three Hicks Muse

investments—two of which are in default, the other in bankruptcy. On

top of that, its $500 million investment (from its third fund) in Regal

Cinema hit the wall when the company declared bankruptcy (it has since

emerged).

For its fifth fund,

Hicks Muse announced it would raise $4.5 billion. It bears mention that

when a firm makes an announcement like that, the bar is always set low,

with the firm expecting to clear it with lots of room to spare (thereby

providing an opportunity to crow about the achievement). The fifth fund

closed in January at $1.6 billion. And Hicks Muse’s Latin American II

fund similarly missed the bar, promising to raise $1.5 billion but only

mustering $150 million.

Amid this poor

performance, with his reputation in the investment world taking a real

bruising, Hicks did something almost unprecedented. He and his partners

made headlines when they guaranteed investors a 20 percent return on

Hicks Muse’s original Internet investments or they would make up the

difference out of their own pockets. Some analysts believe these

investments are now worth 30 cents on the dollar.

Back to Basics—and the Ballpark

All of this is old

news to Tom Hicks, who says his company is back to basics. The rest of

Fund V is being invested in good old-fashioned companies like Swanson

Food, Vlasic Food, and Yell, the British yellow pages company (which

the firm plans to take public soon). In late May, Hicks Muse, along

with another group, bought ConAgra Meats for about $1.4 billion. But

the past—and the running interest on the mistakes of the past—won’t be

easy for Hicks to forget.

Take that famous

guarantee, for example, made late in 2000. “Covering that money

wouldn’t have been a big issue for them in the past,” says Josh Kosman,

a senior writer at the Daily Deal, a financial news publication. “Today

it is a big issue.”

The Hicks Muse

partners made the guarantee by promising a portion of their future

profits from past funds to cover it. Recently they hired an investment

bank to help them find the most efficient way of covering the

guarantees while reducing the carrying costs. According to Kosman, the

partners have already paid down $50 million on the $200 million

principal. With compounded interest, the guarantee on the remaining

$150 million will be worth $180 million next year and $373 million

after four years.

“The problem

for a buyout shop like Hicks Muse is that they have all of these

telecom and Internet companies that have no breakup value,” says Jesse

Reyes, vice president of Venture Economics, a New York-based

venture-capital research firm. “The market has dried up.”

William Quinn, an

investment advisor for AMR’s pension fund, has put $55 million into the

latest fund. “The pressure to get into telecom and Internet investment

really hurt them,” Quinn says. “Clearly they have made some missteps.

But these funds have a long way to go, and you have to take the long

view. They are back into what they do best, and they have done well

with these type of companies in the past.”

Not everyone is so

sure. The Daily Deal’s Kosman thinks the situation is more serious for

Hicks Muse than the firm is letting on. “They are a house of cards

ready to fall apart,” he says. “Ten years ago they were a top 10 buyout

firm. Today they are about 60th, and the problem is, there are just too

many firms chasing too few deals.”

Jay Fewel of the

Oregon Public Employees Retirement Fund, which has invested with Hicks

Muse in the past but passed on Fund V, doesn’t go that far, but he does

sound a cautionary note: “If they don’t do well with this current fund,

it will be difficult to raise money for a Fund VI.”

Others look at the

|

Not

all the problems are New Economy-related. Eyebrows were raised on Wall

Street by Regal Cinema—the $500 million movie theater bomb—and

Viasystems, an electronics manufacturer into which Hicks Muse has

pumped $700 million and whose stock over the last 12 months has dropped

from $4.25 to 7 cents. “These call into question the method, manner,

and care with which Hicks Muse is selecting its investment

opportunities,” says one fund manager.

“You can see

a change in Tom,” says a friend. “Before he owned the Stars and the

Rangers, he was content to sit in the background and make money. Owning

the sports teams has increased his profile, and despite how he protests

about all the publicity, he really likes it. It’s made him a little

more reckless.”

The Man Couldn’t Help Himself

While Tom Hicks

clams up when it comes to talking about Hicks Muse, he can get

positively loquacious about his sports franchises.

Before he bought

the Stars in 1995 for $84 million, Hicks claims he originally had an

endgame in mind—at least that’s what he says now (more on this later).

Hicks says his plan was to invest in the Stars, make them a playoff

team, and get them moved into the American Airlines Center. The

increased revenue would double or triple the value of the team, and

Hicks would walk off with a big wad of cash. (Which is exactly what

fellow arena investor H. Ross Perot Jr. would do with the Mavericks.)

But after he bought the team, Hicks says he looked across town at what

Jerry Jones was doing with the Cowboys and he began to develop a

different perspective. “I used to think sports didn’t make economic

sense,” he told Fortune last year. “But seeing what Jerry did opened up

my eyes to what a well-managed organization could do.”

In his office last

month, Hicks elaborated. “Two things happened to make me look at sports

long-term,” Hicks says. “I fell in love with hockey. Then I started

seeing what the sports business is all about, and I started doing the

buy-and-build thing because I couldn’t help myself. Having the two

teams [he bought the Rangers for $250 million in 1998] changed the

whole dynamic. We had leverage over Fox because we could create our own

network or let Fox pay what it was really worth.” What it was worth to

Fox was $550 million over 15 years, one of the most lucrative media

deals in sports. It was a deal that also placed the Stars and Rangers

among the top revenue producers in their leagues.

Hicks likes to

emphasize that the sports teams are completely separate from Hicks

Muse. And they are somewhat minor investments, considering his entire

portfolio. Before the Stars moved into the new arena last year, they

were costing Hicks about $10 million or more a year; now they make a

small profit. The Rangers are in worse shape. Last year, Hicks

announced a loss of $31.2 million; this year it will likely surpass $40

million. We’ll try to understand what those numbers mean to Hicks—and

just how minor the investment is—in a minute.

Putting money

aside, Hicks’ biggest problem has been the melding of the two

organizations under the Southwest Sports Group umbrella. The Stars and

Rangers now share marketing, ticket sales, media negotiation, and real

estate ventures. “You don’t need two of everything,” Hicks says. “The

Stars play in the winter and the Rangers in the summer. The crunch time

to sell tickets is at two entirely different times. You can use a lot

of the same people to do two jobs.”

Sounds logical, but

the results haven’t been pretty. In 1999, before the SWSG merger, the

Stars won the Stanley Cup and the Rangers won the AL West. Now the

Stars can’t make the playoffs and the Rangers are in last place. The

front office has been a mess, too. Hicks inherited team presidents Tom

Schieffer of the Rangers and Jim Lites of the Stars from the previous

owners. Schieffer was gone fairly quickly. Lites was named president of

SWSG because Hicks knew little about hockey and because Stars general

manager Bob Gainey wasn’t comfortable discussing personnel issues with

him.

To look after the

money, Hicks installed his own man, attorney Mike Cramer, as chief

operating officer. Cramer had once managed the Bumblebee brand for

Hicks, which led some SWSG colleagues to refer to him derisively as

“Mr. Tuna.” Later, he and Lites sparred over personnel and financial

issues, and Lites was gone. Hicks helped Lites get a job with the

Phoenix Coyotes.

“The clash

was between Lites and Cramer, and that was the only clash,” Hicks says.

“Mike Cramer is clearly in charge of the business side, and he and his

team are doing a better job than anyone has ever done.”

The other changes

in the organization are easily explained, Hicks says. Rangers manager

Johnny Oates and Stars coach Ken Hitchcock had lost their teams. “A

manager can only be effective in the pros for a finite period of time.”

Rangers GM Doug Melvin couldn’t “get us to where we wanted to go.”

Gainey, who had told Hicks he would step down two years ago, had become

a lame duck.

But even as he ticks

off the changes and the reasons for them, Hicks has to know that so

much turnover can’t be good. Three levels of management have been

changed in a business where stability usually translates into

championships. Meanwhile, both the Stars and Rangers finished poorly

last year, with an aging nucleus of key players. With both labor

contracts in both leagues coming due in the next two years, the prudent

thing to do, some sports columnists have argued, would be to tear down

the teams and trade veterans for younger players.

Hicks has taken a

different approach. He pushed the payroll of the Rangers up to $105

million this year, with free-agent signings of veterans Juan Gonzalez

and Chan Ho Park, among others. Hicks told me the spending strategy is

crucial, as this is a “crunch year” for the Rangers, meaning that

revenue issues will get better the further the team gets into the Fox

TV contract. Oddly enough, when the team was swept days later by the

lowly Detroit Tigers, Hicks vented frustration over his team’s inflated

payroll, telling the beat reporters, “I’m not doing it anymore. This is

my last year of doing it. We’re going to play within our means from now

on. At least break even.” And he admits that he needs to get butts in

the seats: the Rangers are 160,000 fans behind last year’s pace. To

compound matters, 25 percent of the Rangers 2.8 million attendance last

year were no-shows. That translates into almost $1 million in lost

parking revenues alone, not to mention the profits on overpriced beer

and hot dogs.

But the Stars are

about to undergo a similar spending spree. Not making the playoffs cost

Hicks about $10 million in lost revenue, he says, but he plans to sign

key free agents this summer. “Based on the revenues, we have the

flexibility to be aggressive and we will,” he says. “We are the gorilla

in hockey. We can afford to have a competitive payroll and still make

money. We will be very aggressive.”

The Bottom Line

The financial drain

on Hicks doesn’t end with his investment firm and his sports

franchises. As it turns out, Hicks is also losing money at home. Four

years ago, he purchased the old Crespi estate and later bought

adjoining properties on Walnut Hill, near the Dallas North Tollway.

Last year, he began construction on a new residence. The property is

valued on the tax books at $26 million. Sources close to Hicks say the

house and other improvements were originally budgeted at $30 million

but could now exceed $50 million.

On the surface,

Hicks has every reason to indulge himself. Hicks Muse has an estimated

$12 billion under management (though it’s tough to gauge because so

many of their investments have shed value). Without making another deal

or raising money for another fund, Hicks Muse could comfortably coast

until at least 2007. Its management-fee income is north of $80 million

annually, which, after operating expenses, earns the partners perhaps

$60 million, probably netting Hicks himself $15 million a year, after

taxes.

Tom Hicks’ net worth,

as calculated by Forbes, is around $700 million. But that’s a deceiving

figure. When you have a lot, you spend a lot. Net worth is one thing;

liquidity is something else entirely. Hicks’ money is tied up, some in

outside investments, some in Hicks Muse funds. Ready cash is a scarce

commodity, no matter how many zeroes you have on your balance sheet.

So when you try to

see where the cash is going to come from to keep the Rangers afloat,

the clouds start to roll in. Hicks is being hit from a number of

different areas. He and his partners have to pay off that Internet

investment, and the interest clock is ticking at $30 million a year.

The Rangers are hemorrhaging money at the rate of $40 million a year

(and the impending work stoppage in major league baseball doesn’t bode

well for owners). The first four Hicks Muse funds are maturing, which

means the management fees will be leveling off. Meanwhile, the firm’s

anticipated share of profits is being eaten by flawed investments such

as telecom, Regal, and Viasystems.

Now, much of this

is informed conjecture, and nobody knows Tom Hicks’ personal financial

situation except Hicks, his wife, a couple of the original partners,

and maybe a banker or two. But put in perspective, the prospect of

writing $40 million checks for the Rangers doesn’t seem as minor as

Hicks makes it out to be when he’s chatting with a reporter. It makes

one wonder if Hicks blew up at the Dallas City Council over the Victory

project because he doesn’t like the way the city operates—or because he

flat-out needed the cash. It also makes one wonder why he might now

claim that, before he bought the Stars, he planned to sell the team all

along. Could this be a rich, though cash-strapped, man laying the

foundation to cover his posterior when he does sell? This line of

questioning might illuminate the recent release of the $6 million Ed

Belfour in favor of the $850,000 Marty Turco. Decreasing payroll to

improve cash flow outlook is sometimes termed “dressing up Grandma” in

deal circles.

Certainly the

vultures are hovering. The Daily Deal’s Kosman sounds a common theme:

“If we looked at Tom Hicks in January 2001, he was ranked in the top 10

of all private equity firms, he was on the top of the sports world, his

personal friend had become president, and there was talk of his being

named Treasury Secretary. All the stars were lining up for this guy.

Now his firm’s in some trouble, his sports teams are terrible, and he

was passed over for a cabinet post. It’s amazing how quickly all of

this has caught up with him.”

It’s also amazing

how quickly it could turn around. A solid performance with Swanson

frozen dinners and Vlasic pickles, a smashing IPO for the British

yellow pages, development of new offices and apartments around The

Ballpark in Arlington, a pennant for the Rangers, and another run at

the Stanley Cup for the Stars—all that would scatter the clouds and

bring sunshine once again to the world of Tom Hicks.

Then again, I

shouldn’t make such assumptions. None of these occurrences would affect

any of the others. None of the dots are connected. That much Mr. Hicks

has told me.

Fort Worth-based

freelance writer Dan McGraw is a former senior editor for U.S. News

& World Report. He is currently working on a biography of football

great Johnny Unitas.

Photo by Kris Hundt