In each of the last three seasons, Rodriguez has hit 40 home runs. In 1998, he hit 42 home runs and stole 46 bases. Only three players have ever had 40/40 seasons—and never a shortstop. Among shortstops, only Ernie Banks (who was born in Dallas) has hit more home runs in a single season. Given the hitter-friendly set-up of The Ballpark in Arlington, it’s only a matter of time before “Mr. Rodriguez” surpasses “Mr. Cub.”

Larry Bowa, current manager of the Philadelphia Phillies and World Series-winning shortstop, has said of Rodriguez, “He’s the kind of player who comes along once every 50 years. He has it all. If you were going to build a franchise, that’s the guy you’d start with. There’s nothing on the field that he can’t do.”

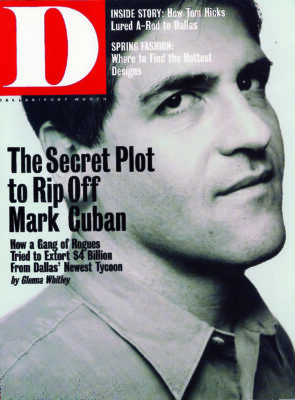

Hicks was all too aware that the only image Rodriguez had of Dallas—as a member of a visiting team—was the roller coaster at Six Flags, a few chain restaurants, and the gentlemen’s clubs that surround the Ballpark. It’s a 30-minute cab ride from Arlington to any kind of urban nightlife. So, with that in mind, Hicks was waiting at the airport that Sunday afternoon to show Rodriguez and Boras his Dallas. Using Texas-style charm, Hicks made it his personal mission to give Rodriguez a different look at our city.

On Monday they drove through the older parts of Arlington and Highland Park. They cruised through Preston Hollow and down to the American Airlines Center construction site for a hardhat tour. Hicks pointed out the Victory Project that will eventually surround the arena with offices and residential and commercial buildings. He let Rodriguez know that he was creating a similar urban environment around The Ballpark in Arlington.

Hicks, as usual, had done his homework. He knew that Rodriguez liked city life. When Rodriguez played in Seattle, he was the only member of the team who lived downtown, to be close to the action. As the men drove around town, Hicks learned that A-Rod (a name reserved for baseball writers and teammates) loved fine dining, golf, and movies. They talked as potential owner to potential player. The fact that Hicks took the time to greet him made a big impression on Rodriguez who, during his five years in Seattle, had never even met the 72-year-old owner of the Mariners, who lives in Japan.

As he prepared for Rodriguez’s arrival, Hicks covered every base. He knew that Rodriguez was looking for a long-term deal where he could finish out his baseball career and parlay himself into a successful businessman. Taking that cue, Hicks pointed out that Dallas was loaded with corporate headquarters and opportunities for endorsement deals. Future partnerships were just a Tollway exit away.

Hicks also called in his closer, Mike Modano, the 30-year-old poster boy of the Dallas Stars, to seal the deal. When Rodriguez’s representative, Lisa Gilson, heard that Hicks had arranged for the two to eat dinner together, she told Rodriguez, “I think you two will really hit it off and be friends. You both like the same things—golf, good restaurants, and Armani.”

Rodriguez didn’t know anything about hockey, but he was impressed with the way that Hicks had built a Stanley Cup winner around Modano. Earlier that afternoon, Hicks and the Rangers had promised Rodriguez that they were willing to build the Rangers around him, complete with a Power Point presentation of the Rangers’ farm program.

On Monday night, Rodriguez, Scurtis, and Boras met Modano and Modano’s date at Bob’s Steak & Chop House. Over 16-ounce filets and a $100 bottle of Cabernet, the two super-jocks shared game-day rituals and scheduling horror stories. But Rodriguez really sat up and listened when Modano related how easily he had adapted to life in Dallas. “I told him how laid back and friendly the people are,” says Modano. “I’ve played here for eight years and I love it. I’m going to make it my home after I retire. A-Rod really seemed to want that, too.” Unprompted, Modano told Rodriguez how his relationship with Hicks had developed to a level where Modano could comfortably confide in Hicks about his own business opportunities.

After Modano dropped him off at his hotel, Rodriguez called Gilson and exclaimed, “Wow, Modano gave me some really good information. You weren’t lying!”

The next morning, as Rodriguez boarded his private jet to fly to Las Vegas for a round of golf, he called Boras and told him to put Texas at the top of the list. Evidently, Hicks’ charm, Modano’s honesty, and Bob Sambol’s steaks had captured Rodriguez’s attention. But there were still negotiations to be conducted.

Tom Hicks made a name for himself negotiating business deals. Beginning in the early ’80s, Hicks and then partner Robert Haas entered the leveraged buyout game. Their concept was simple: buy a company, add acquisitions in the same industry, sell off superfluous assets, grow the business, and then sell for a pot of cash. Hicks and Haas produced hundreds of millions of dollars in profits for their partners and themselves.

Their first home run came in the mid-’80s when they purchased A&W Root Beer for $72 million, Dr Pepper for $416 million, and Seven-Up for $240 million. In less than two years, Hicks and Hass out-maneuvered Coca-Cola and Pepsico to dominate the non-cola market in the United States. When they sold the companies to Cadbury Schweppes in 1995, the return for investors was 24 times their original stake.

In 1989, Hicks and Haas split. Hicks formed a new investment firm, Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst, which has expanded the “buy and build” strategy, raising and investing billions of dollars on behalf of institutional investors in radio, oil and gas, and food processors. After more than 20 years of financial success and only a handful of failures, the word on Tom Hicks is that if he lets you into a deal, you’re in good hands.

Hicks got into the sports business when he bought Norm Green’s “NoStars” in December 1995 for $85 million. Once the deal was inked, Hicks started building toward a Stanley Cup. The Stars were in the bottom third of the league in terms of total payroll, so Hicks opened up his checkbook, buying big-name players such as Joe Nieuwendyk, Pat Verbeek, Ed Belfour, and Brett Hull, and along the way, renegotiating a five-year deal to keep Modano as his marquee player. By the time he was through shopping, Hicks and General Manager Bob Gainey had put the Stars in the top tier of the league in payroll.

Despite the lack of revenue from luxury boxes in Reunion Arena, Hicks catapulted the Stars to the third highest revenue-producing team. Since Hicks’ acquisition of the team, the Stars have won three consecutive Division Championships, two Presidents’ Trophies as the team with the best regular season record, and in 1999, won the Stanley Cup. Last season they lost in the finals to New Jersey. Next fall, when the Stars move to the American Airlines Center, Hicks will cash in, receiving revenue on everything from catered corporate dinners in the luxury suites to the nachos and beer spilled in the stands.

Hicks bought the Rangers in June 1998 for $250 million from the partnership that included Rusty Rose and Tom Schieffer, and then part-time, play-by-play announcer and batting practice bench-warming businessman George W. Bush. In addition to the franchise, Hicks acquired the lease to the Ballpark and the 270 acres that surrounds it.

Clearly the Rangers needed to improve their image. They had never been considered a quality baseball franchise until they opened the new ballpark in 1994. Though the Rangers have taken three American League division titles in the last five years, in their last two playoff appearances, they were swept by the Yankees. Front office frustration mounted before the 1999 season when the Rangers lost a trade for Roger Clemens and a chance to sign Randy Johnson. Luckily, at the same time, they reacquired designated hitter Rafael Palmiero, who, once back in a Ranger uniform, turned in the best performance of his career.

The Rangers were competitive, but Tom Hicks is not in the sports business to be competitive; he’s in it to win. “I believed that we needed to boost the visibility,” Hicks says, “so I went for Alex.”

If Hicks could sign Rodriguez to a long-term contract, he would own two valuable sports franchises, both with highly marketable superstars, and both playing in state-of-the-art, revenue-maximizing facilities surrounded by developments that Hicks has interests in. It sounds like a fantasy scene from Wall Street. But Hicks still had to get Rodriguez and his agent to terms.

If anybody was willing to meet Boras’ demands, it was Hicks. He had already shown agressive tactics to buy and build businesses—whether they sell soft drinks or shortstops. Hicks and Boras had developed a relationship last winter while negoiating contracts for Boras’ clients Kenny Rogers and Darren Oliver, both pitchers who signed with Texas.

Hicks is also known as a consistent businessman. By contrast, Baltimore Orioles principal owner Peter Angelos, a successful plaintiffs lawyer, is known for erratic and irrational dealings. He’s been through four general managers, five managers, and six pitching coaches in seven seasons. Angelos has plunged the Orioles’ reputation to an all-time low. During the off-season, while Angelos’ players were warning potential Orioles to stay away, Pudge Rodriguez and Raphael Palmiero were making regular calls to A-Rod urging him to come to Texas.

When this year’s bumper crop of free agents hit the auction block, Rodriguez was in a position to take bids from any team that could afford him. All educated eyes were on the obvious contenders—the Braves, Mariners, Mets, Dodgers, and Rockies, with the Rangers running at the back of the pack. Rumors swirled, but Boras kept quiet.

Hicks, who had no sense of what the other teams were thinking, had to come up with his own economic justification. After getting swept by the Yankees in 1999, he dropped his payroll from $83 million to $49 million, enabling him to be aggressive in rebuilding the Rangers. He went on a spending spree, signing first baseman Andres Galarraga for $6.25 million, third baseman Ken Caminiti to a contract that could be worth $20.9 million over three years, and reliever Mark Petkovsek for $4.9 million over two years. Even after those, Hicks pushed forward in his pursuit of baseball’s Holy Grails: Alex Rodriguez and a World Championship.

One by one, the Mets, Dodgers, and Rockies dropped out of the running and Boras was left with three final bidders: Seattle, Atlanta, and Texas. What Hicks didn’t know at this point was that Atlanta wouldn’t give Rodriguez the no-trade clause he wanted and that Seattle’s $92 million offer was for only five years. During the bidding, Rodriguez and Boras consistently floated the $20 million-a-year figure, plus the importance of a no-trade clause with a long-term commitment.

At the mid-winter meetings, Boras and Hicks finally holed up in the Anatole, spending more than 10 hours behind closed doors. The toughest part of the negotiations between the two was that Boras wanted a free agency escape hatch every three years; in order to make the financial committment Boras was asking, the Rangers wanted a locked-in, long-term commitment of their own. Just two weeks after A-Rod’s tour of town, they worked out the final details on a contract that, including deferred payments of $36 million, adds up to $252 million. “The deal has a present value of $180 million,” boasts Hicks. “And he’s ours for seven years. No matter what.”

When the news reached Baltimore of the record-shattering contract, sports fans there must have wondered if Hicks had just replaced Angelos as the craziest man in baseball. But the economic rationale isn’t the same for every buyer. Hicks, who can put an optimistic pitch on any situation, states calmly, “We can pay this kind of money and make a profit. I like to build things, whether it’s a $2 billion corporate acquisition or a chance to win the World Series.”

Hicks’ business model for both the Stars and the Rangers is to keep the payroll at 55 percent of total revenue, all the while continuing to make player improvements and searching for additional revenue sources. For instance, on his television contract alone, Hicks packaged the Stars and Rangers in a deal with Fox SportsNet, which will pay an estimated $550 million for 15 years of cable rights and 10 years of Fox’s local TV (channels 4 and 27) broadcasts.

Hicks plans to recoup half of Rodriguez’s 2001 salary—$22 million in real dollars—from higher ticket prices and increased concession sales. The concession sales projection stems from a bet that the Rangers will see a smaller percentage of no shows than in previous seasons. If the team makes the playoffs, Hicks figures he’ll recoup the other half. If the Rangers end up in the World Series, Hicks says matter of factly, “We will make money on our investment in Alex.”

Now more than just the eyes of Texas are on Tom Hicks. He’ll either be the hometown hero who brings the first baseball ticker tape parade to Dallas or the free-spending villian who sent baseball to economic ruin.

Given Hicks’ track record, we’re lining up for the parade.