THE LEXUS-DRIV1NG, ARMANI-CLAD CONTINGENT INCHES ITS WAY underground, into the parking garage of Thanksgiving Tower. In clusters, they wait for the elevator that will take them to the Tower Club, that den of Dallas deal-making on the 48th floor. It is the third Saturday of the month; dozens of power brokers are filing in for the quarterly Federal Club luncheon. The local arm of the political action committee known as the Federal Club was originally-and presciently-called the Dallas Insiders. Its founding members, insiders all, set the deceptively simple agenda in 1987: Club members meet for lunch four times a year to network and to hear a speaker of national prominence, usually a congressional leader in support of the club’s political agenda. Dues-up to $100,000 a year-go directly to Washington, D.C., toward Federal Club causes.

Almost 10 years later, as membership has ballooned to more than 300, the club has developed the kind of cachet usual lyre served for Dallas’ old-line institutions, becoming as much-if not more- a social vehicle as it is a formidable PAC. Members ante up big money to belong and, in return, they’re afforded varying degrees of political clout-not to mention significant helpings of that elusive, but highly essential, component of the Dallas power game known as social entree. They are among the city’s top lawyers, doctors, real estate brokers and businessmen and women. They share space on that tier of Dallas society reserved for the monied elite. They are among the city’s most prolific movers and shakers.

And virtually all of them are gay.

STRAIGHT DALLAS ISN’T ACCUSTOMED TO SEEING ITS PIN-striped, button-down reflection in the gay community. The popular perception of Gay Dallas is built on images set against a backdrop of the bars along Cedar Springs. In the annual Halloween Parade, gay men in high heels and tutus flaunt their homosexuality and the assumption is that this corner of the gay community is the gay community. The reality is this: Like Dallas itself, Dallas’ gay and lesbian community has a conservative, white-collar, churchgoing, well-connected, white-male core. “We may be seen marching in a parade during Gay Pride week, but we have our briefcases and our coats and ties on every other week,’* says Alan Levi, chairman of the local Federal Club. “If someone came to a Federal Club luncheon and didn’t know better, they’d walk in and think it was some conservative business group.”

A conservative business group with considerable clout.

Early on, Dallas’ gay and lesbian community adopted the city’s businesslike approach to effecting change, realizing that-in Dallas-power is conferred upon those with the financial clout to get things done. Straight or gay.

Nationally, the gay rights movement has been characterized by a strong Them-vs,-Us attitude. In San Francisco, New York, Miami, even Houston, the approach has been radical, on-the-fringe, in your face, unDallas. Believing “we wouldn’t be successful if we didn’t do it the Dallas way,” as Craig McDaniel says, the Dallas gay and lesbian community has charted a higher course, aligning itself with the city’s mainline establishment. “This is the way we do things here,” says McDaniel, the first openly gay man to win a seat on the Dallas City Council. “In Dallas, we get ourselves organized, we’re business-oriented. They’d laugh at you in Chicago or Philadelphia if you tried to do things the way we do here.”

Taking its cue from Straight Dallas, Gay Dallas has successfully worked the system through established centers of power:

POLITICAL: The Federal Club is the major-donor arm of the Human Rights Campaign, the largest political organization devoted to promoting gay and lesbian issues on a federal level. The Dallas/Fort Worth chapter of the Federal Club is the largest in the United States, contributing more than $350,000 a year to the Human Rights Campaign fund. What Team 100 is to the Republican National Committee, the Federal Club is to the Human Rights Campaign.

SOCIAL: The annual Black Tie Dinner, benefiting the Human Rights Campaign and local gay and AIDS service organizations, is the largest sit-down dinner in Dallas. Since its inception 15 years ago, this annual event at the Anatole has raised in excess of $2 million. Last year’s attendance (3,000 plus) was more than double that of the San Francisco Black Tie Dinner. What the Crystal Charity Ball is to Straight Dallas, the Black Tie Dinner is to Gay Dallas.

RELIGIOUS: The Cathedral of Hope Metropolitan Community Church is the largest predominately gay and lesbian congregation in the country, with an annual budget of $2.4 million and 3,000 regular attendees. Senior pastor Michael Piazza last year commissioned renowned architect Philip Johnson (the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, Calif.; The Crescent in Dallas; the Seagram Building in New York City ) to design MCC’s new sanctuary, what Piazza envisions as “a psychological cathedral for gay and lesbian people around the world.” Estimated cost: $20 million. What First Baptist is to Straight Dallas. Cathedral of Hope MCC is to Gay Dallas,

ARTS: The Turtle Creek Chorale, alternately the largest/second largest gay men’s chorus in the country, performs to sold-out audiences at the Meyerson and is scheduled to give one of the first public concerts following the 1998 opening of the Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass Performance Hall in Fort Worth. Under the direction of Dr. Timothy Seelig.TCC has recorded 13 CDs, making it the most recorded male chorus in history-and the subject of its own Emmy-winning documentary. Straight Dallas has nothing that compares with the Turtle Creek Chorale.

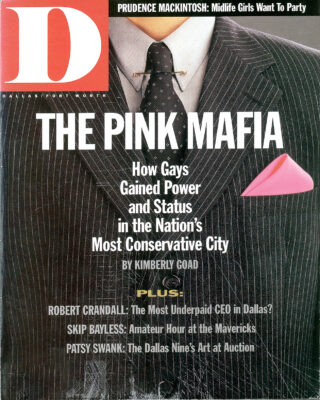

These nets of influence overlap to create an underground wet) of power not unlike a secret society-a sort of Pink Mafia-in which a select few call the shots. While they may not (necessarily) be the ones rehearsing with the Chorale on Tuesday night at the Sammons Center for the Arts or worshipping at Cathedral of Hope MCC on Sunday morning, the members of the Pink Mafia effect change from the uppermost reaches of Gay Dallas’ social strata, anointing up-and-comers in the Federal Club, getting gays and lesbians elected to public office and penetrating Straight Dallas institutions like the Dallas Assembly. Through its not-insignificant muscle, the Pink Mafia has molded Gay Dallas into the mirror image of Straight Dallas. A perfect social order in which the Gay haves bear more than a passing resemblance to the Straight haves.

That was the plan. After all. this is Dallas.

The Dallas gay rights movement was designed by a core group of gays and lesbians, professional men and women who came together almost 20 years ago to map out a strategy. This being Dallas, it was essentially a business strategy. They drafted a mission statement. They set four goals. They established point-by-point “ways and means” of achieving each goal, illustrated with elaborate time lines. Then they christened it.

Appropriately, they called it The Dallas Approach.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1977, A BOOMING REAL ESTATE MARKET WAS giving new meaning to the idea of living big in Dallas. There were clues to the existence of gay life, but only to those willing to look for them. Metropolitan Community Church of Dallas had a congregation of 176. Gay bars like the Old Plantation and groups like Circle of Friends provided social outlets. A popular weekly radio show called “Just Before Dawn” (on the old KCHU-FM) had a cult following. And the Dallas Gay Political Caucus was a tiny group of gays struggling to form a gay movement.

The Caucus (now, the Dallas Gay and Lesbian Alliance) was a year old that summer of 1977 and already it was suffering an identity crisis. Eight years after the birth of the modern-day gay rights movement-the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City-the anti-gay sentiment was gaining momentum. Anita Bryant dominated headlines with her fight to overturn a Dade County, Fla., law prohibiting discrimination against gays, and the case became a rallying point for homosexuals nationwide.

The Caucus’ board members gathered on a June weekend with the intention of charting a new course. Louise Young, Ph.D., a land use planner, hosted the two-day strategy session at her home near White Rock Lake. On hand that weekend: an elementary school teacher (Don Baker), an architect (Steve Wilkins), an attorney (Dick Peeples) and an insurance adjuster (Jerry Ward). All of them professionals; all of them first-wave baby boomers who had emerged from the crucible of the ’60s with “fire in the belly,” as Don Baker says.

“The main focus was on how to deal with the anti-gay sentiment stirring around the country as a result of the campaign Anita Bryant was waging from Florida,” says Young. ’This was all new territory. We felt that we were on the crest of a wave, that everything was possible.”

The group had two objectives: build a gay community in Dallas; then bridge it with the non-gay community. They were determined to organize an effort distinctly different from others forming across the United States. Other cities had stayed segregated and tended to be, says Young, “more reactionary than ’actionary’.” The Caucus recognized, even then, the importance of taking the organization down a path in which the gay and lesbian community was seen as a part of the larger community.

They were an unlikely band of revolutionaries. There was Young, the conservative Texas Instruments executive. There was Peeples, the attorney in the group who kept the Caucus in line on legal matters and financial concerns. Baker, a teacher at Daniel Webster Elementary, was the dreamer; his proposals were far-flung and usually shot down as unrealistic. Ward, the insurance adjuster, was the inclusive-thinking member, the one who made sure the group’s goals addressed all segments of the gay and lesbian community. Wilkins, meanwhile, was the charismatic figure. Remembered as much today for his sartorial flair and the Triumph he drove as he is for his work, Wilkins was the logical spokesperson for the Caucus. The only member of the group who was totally out at the time, he was also the only candidate for president, given the Caucus’ mandate against electing a closeted president.

By the end of that weekend in June, they had developed a master plan with four goals: repeal Section 21.06 of the Texas Penal Code, which prohibited private homosexual activity between consenting adults; educate the community about homosexuality; establish city ordinances that would protect the civil rights of gays and lesbians; and provide community services for homosexuals.

“It was very systematic,” says Baker. “Because we had professional backgrounds, we implemented a plan that was very professional.”

And very Dallas. It was Wilkins who came up with die name. The Dallas Approach.

After that weekend they began meeting once a week and devoting weekends to die cause. They embarked on an extensive letter-writing campaign to introduce the Caucus to politicians. They produced a brochure (“Questions and Answers about Homosexuality”) as a means of dispelling stereotypes in an age when most people thought they didn’t know any homosexuals. They stood on what’s known as the Crossroads (Cedar Springs and Throckmorton) and distributed voter guides detailing candidates’ stands on the issues. They set up voter registration tables outside bars and businesses on Oak Lawn, and then used the information to create a master mailing list to keep gays and lesbians politically informed. They hosted a conference “to explore the prejudice against homosexual men and women…in relation to the church” at Northaven United Methodist. And lest their efforts appear to be in vain- this is Dallas, after all-the media were always alerted. They were working the system.

When Young and Wilkins traveled to Denver the summer of ’77 for the first National Gay Leadership Conference, “a virtual Who’s Who for people who were in [he movement,” as Young recalls, they measured their efforts against those of their counterparts. “These folks were the ones who started the gay liberation front in the major cities following Stonewall,” she says. ’Their approach differed from ours because we were trying to gear it to Dallas, while they were taking a more- I hate to use the word radical-confrontational approach.”

Young still remembers the reaction to Wilkins, “this guy standing before them in a three-piece suit and wingtip shoes,” as he proposed his idea for a national ad campaign portraying gays and lesbians as family members set against a rendition of “We Are Your Children.” Says Young, “I think they thought we were a little out of step.”

Still, the Caucus stayed true to its intent-establishing what Wilkins called “a firm, rational gay presence in the Texas mind.” When Anita Bryant announced her plans to make an appearance in Brownwood. west of Fort Worth, that same summer, the Caucus decided against staging any sort of group protest. Instead, they hired a professional writer, a layout artist and a newspaper production specialist to create a full-page ad denouncing Bryant that ran in the Brownwood paper. Then the Caucus notified the Florida Citrus Commission, which Bryant was representing in orange juice ads, to say the Caucus opposed the nationwide “gaycott” of Florida citrus products believing it would be counterproductive and “would deny her the right to work, a right that has often been denied to us.”

“The board of directors drafted a philosophy that was unique in America,” says Don Baker, who later agreed to become the plaintiff in the landmark 21.06 case. “It said, Dallas is Dallas. It’s not New York or San Francisco. And how we go about the business of gay rights has to be in tune with the culture in which you live. That set the tone, the tenor and the temperature of the gay rights movement in Dallas.”

Indeed, even as AIDS forced the movement to switch from a political focus to a social one. The Dallas Approach could be seen in the way the gay community organized its services and in the way it objected to the general apathy toward the AIDS crisis.

Not surprisingly, the radical gay activist group known as ACT UP-AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power-never had much success in Dallas. Instead, there was GUTS.

The Gay Urban Truth Squad, led by activists William Waybourn, Bill Hunt, Bill Nelson and John Thomas, decided early on to adapt to Dallas’ longtime aversion to confrontation while still using action to make a point. When GUTS staged a protest, streets were never blocked, no one was arrested. A GUTS protest was more like a cleverly orchestrated, photo-worthy street drama. In 1988, for instance, the bottom had already fallen out of the Dallas real estate market. The empty lot on the corner of Cole and Lemmon had been cleared for development only to have the developer, Larry Lassiter, file for bankruptcy when the S&L behind the project failed to deliver on a $157 million loan. Declaring the empty lot a safety hazard, the city council voted to spend $500,000 to fill the giant hole (“this city’s version of the Grand Canyon.” said a Dallas Morning News editorial) the same year it voted to allot $55,000 to AIDS funding. Thirty-five members of GUTS arrived on the scene after the hole was tilled and turned it into a potter’s field, hammering into the ground hundreds of white crosses bearing the names of people in Dallas County who had died of AIDS. Before GUTS left, the group erected a three-part sign: “The City of Dallas Spent $500,000 Filling This Hole/The City of Dallas Spent $55,000 on AIDS/Dallas County AIDS Deaths Equals 793.” The “protest” was carried on the evening news. The following year, AIDS funding increased to $552,000.

IN THE MID-’80s, DON MCCLEARY WAS NOT UNLIKE A LOT OF successful gay men in Dallas. Prominent attorney on a fast track to managing partner. Unlimited access to the city’s power brokers. All the accoutrements of the good life: beautiful wardrobe, expensive car. well-appointed home. By all appearances, Don McCleary had it all. He was charming, good-looking, well-to-do, connected…and closeted.

“Don struggled long and hard with his sexuality.” says friend Larry Pease, an account executive with Sunbelt Motivation & Travel. “He had been married, struggled with his orientation and recognized that it would have been far easier to rise in the ranks of legal circles-in Dallas and Texas and nationally-were he willing to remain la happily married man.’ Once he determined it would be impossible to deceive the world and himself, Don threw himself into effecting positive changes within the gay community he found himself, somewhat reluctantly, a member of.”

McCleary had limited much of his activism on behalf of the gay and lesbian community to behind-the-scenes power-brokering and check-writing. By the mid-’80s, as AIDS threatened to wipe out an entire generation of gay leaders, the epidemic galvanized checkbook activists like McCleary, forcing them out of the closet.

In 1987, it was clear to McCleary that gays and lesbians could continue to spend big lobbying dollars in Austin and the impact on their own lives would be negligible, By then. Baker vs. Wade- the Dallas case in which the state’s homosexual conduct law (Section 21.06) was ruled unconstitutional-had been overturned on appeal. The only way to effect real change was to build political clout on a national level.

To that end, McCleary pulled together a small group of prominent and influential gay professionals interested in supporting the Human Rights Campaign, the $ 1 million PAC dedicated to securing equal rights for gays and lesbians. McCleary christened the group the Dallas Insiders, then set up a recruiting lunch at the Crescent Club. Each Insider submitted a list of friends successful enough to consider contributing a minimum of $1,200 a year to the Human Rights Campaign fund.

At the Crescent Club, pledge cards were set up on each table as a representative with the Campaign pitched the Dallas Insiders on the idea of supporting the political organization through six membership categories (from $ 1,200 to $ 100.000). That day. 65 Insiders pledged at least $ 1,200 apiece to the Campaign. And seemingly overnight the Dallas Insiders became a gay and lesbian group with considerable political clout.

“Very early on, we were entertaining and receiving people as prominent as Sen. Charles Robb and Lynda Bird Johnson of Virginia,” says Larry Pease. “Sen, Tom Harkin of Iowa appeared before us three or four times. They were among the first politicians who sought the financial support of the Dallas Insiders- and, obviously, we couldn’t vote for them.”

Over the five years that followed, leaders of the Dallas Insiders negotiated the renaming of the organization. More than a few felt the name conjured the wrong image and preferred, instead, the name the Human Rights Campaign already had in place-the Federal Club-for individuals who contributed the minimum $1,200 a year.

Almost 10 years after the Insiders met for lunch at the Crescent Club, what’s now known as the Dallas/Fort Worth chapter of the Federal Club is the largest in the United States. And, as McCleary predicted, the funds filter back to Dallas directly and indirectly. More than 30 gays and lesbians now sit on city boards and commissions. Jose Plata was elected to the DISD board as an openly gay man. Three gay men sit on the Dallas City Council.

’’At a point, numbers are not as important as dollars in a cause,” says Dallas Realtor Mike Grossman, ’it takes a lot of money and a lot of political clout. You don’t get political clout from anything but money.”

Grossman, among the original Dallas Insiders, now presides over Uptown Realtors, considered the largest gay and lesbian real estate business in the country. He still recalls his first trip to Washington. D.C., for a Federal Club conference in the days when the Democrats still controlled Congress. “They had a luncheon as part of the functions. Ted Kennedy sat right here; Pat Schroeder sat right there. I mean, it was like six or seven tables of Federal Club members and there were two to three heavyweight politicians at every table.” He pauses for emphasis. “You have to understand, that was real impressive. Gerry Studds and Barney Frank have both stayed in my home. They both have my home phone number and I have theirs. You feel really important when you have credibility, when you can share that credibility with others and tell people: ’You can have it, too, Give us 1,200 bucks.”’

NOT ALL GAYS ARE CREATED EQUAL. Consider the distance from Cedar Springs to the rarefied levels of the Pink Mafia. There, they operate on a standard that is, well, Dallas. Status is measured by the Lexus they drive, the straight church they belong to, the degree of preferential treatment at Parigi, the dollars they contribute to the Federal Club.

Their names make up the A-list of Gay Dallas.

They are the A-Gays.

Writer Armistead Maupin coined the term in Tales of the City to describe members of the socially prominent class of San Francisco’s gay community. In Dallas, where the classes are divided along different lines, the A-Gays are typically more conservative- and less out. To understand their role within the Pink Mafia is to understand the nature of the Dallas power game. In Dallas, real power doesn’t depend on good intentions, but on financial wherewithal and the willingness to use it. Thus, the ruling class of the Pink Mafia is made up of A-Gays; though not all A-Gays are destined to rule within the Pink Mafia. Dallas/Fort Worth Federal Club chairman Alan Levi is a Dallas accountant. Many of his clients are Federal Club members. He knows: “For some, that S 1,200 is a stretch, but they look at it as a necessity.”

Gay activists fighting on the front lines in the days when AIDS was known as GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) look upon this kind of dues-paying with scorn. But it’s dues-paying that A-Gays relate very well to. Although many in the movement decry the Federal Club as elitist and begrudge the A-Gays for leading what they see as double lives, they admit that-in Dallas–you can never discount the power of snob appeal.

Meanwhile, high-levelA-Gays straddle Gay and Straight worlds with varying degrees of success. They speak a code language in which words like “community” and “empowerment” and “pride” take on different meanings depending on the orientation of the listener. Lest anyone think, for instance, that Uptown Realtors is specifically targeting the gay and lesbian community through its ads on KERA-TV Channel 13, the company talks about “serving and reflecting the diversity of Dallas” by carefully avoiding the G word and the L word altogether.

“It’s not a popular view,” says John Thomas, “but I think our own worst enemy in the gay community is the gay person who would rather hide and lie than tell the truth. Others would say, ’You don’t understand, it’s dangerous to come out, you may lose your job.’ It’s not that I think they’re bad or wrong for it, but I do think they’re the drag on the movement.”

Thomas, arguably the city’s most visible gay leader, stepped down as executive director of the AIDS Resource Center early this year. Now battling the disease himself, he no longer has the strength to run the center he helped found in 1985. While Thomas is the first to say that coming out is a process, he also believes the high-level A-Gays could use their influence to greater benefit if they were completely out. Don McCleary, for instance, “had an influence among the insiders of the Federal Club. Outside of that, most people in the gay community wouldn’t have known who he was,”Thomas says. “When Don died, we were close friends. But back in the mid-’80s we had a definite difference-he was closeted. He was heading up the Federal Club and he was closeted.”

The relationships between openly gay activists like Thomas and A-Gays like McCleary were actually symbiotic. Closeted gays and open gays have always used one another to mutual advantage- especially in penetrating Straight Dallas institutions, which was key to achieving the second half of the movement’s original objective: to build a bridge between Gay Dallas and Straight Dallas. In 1993, McCleary nominated Thomas to membership in the Dallas Assembly, the prestigious civic organization of Young Turk types which had yet to offer membership to an openly gay person. McCleary, already a member of the organization, submitted the name of Thomas, whose name and face had come to symbolize the gay rights movement in Dallas.

“Part of the irony is that Don didn’t consider himself open,” says Thomas. “So I was the ’first gay person* in the Dallas Assembly.” He laughs. “Because they do a directory and figuring I certainly wanted to push the envelope as Don would want me to, I listed, as my spouse, ’Gary Lanham’-and they printed it. Don never put his partner in.”

McCleary, in fact, didn’t come out until his sexual orientation threatened to keep him from rising to managing partner at Gardere & Wynne. The law firm was on the verge of financial collapse in 1991 when the other partners, believing McCleary’s orientation could be detrimental to the firm, denied him the position. McCleary, in turn, decided to use the clout he’d been accruing. He quietly contacted a number of the firm’s key clients and informed them of the resistance he was encountering from the other partners. Many of these clients-corporate counsels who make the legal hiring decisions-themselves were members of the Pink Mafia. When they let it be known they might follow McCleary out the door, resistance to McCleary’s becoming managing partner collapsed. A compromise was reached. McCleary, promising to keep his private life private, was named co-managing partner.

For further proof of the kind of power the Pink Maria members wield, look at those comers of the gay and lesbian community operating outside its presence. In the absence of the Pink Mafia, there exists a sort of gay ghetto, segregating Gay Dallas from Straight Dallas. At Cathedral of Hope MCC, for example, controversy surrounds its new $20 million Philip Johnson design.

The architectural model of the 2,000-seat sanctuary-longer than two football fields and as tall as St. Patrick’s Cathedral-was unveiled on MCC’s 26th anniversary last summer. Senior pastor Michael Piazza, looking to raise seed money for the project on what he called Miracle Sunday, raised $143,000 toward Johnson’s design fees. Ask the pastor how he plans to raise the remaining $19 million-plus and he says. “That’s the $20 million question.”

Indeed, the Cathedral of Hope MCC lacks a strong presence of A-Gays within its congregation. Believing the church is “too gay,” as one successful gay man put it, A-Gays typically worship at Dallas power churches like Highland Park Presbyterian and First United Methodist. As a result, Piazza is forced to look outside the church and outside the city for the bulk of the funds. The church has hired William Waybourn, the former Dallas gay rights activist who now presides over Window, a Washington, D.C., public affairs firm that manages and organizes media, marketing and fund-raising campaigns for gay and lesbian organizations.

Waybourn declines to discuss the specific fund-raising strategy. Piazza, however, estimates that $5 million will be raised within the congregation, $5 million to $10 million from local philanthropists and the remaining millions from the national campaign. Both admit the project won’t be finished for at least five years.

Piazza, a popular and charismatic figure, is savvy enough to adopt the key passage from The Dallas Approach (“You have to spend money to make money”). Yet he clearly doesn’t understand the basic rules of the Dallas power game.

Consider the night the gay city councilman showed up for a late dinner at Parigi following a Turtle Creek Chorale concert at the Meyerson. He and his companion arrived at the chic Oak Lawn restaurant minutes to closing. As they waited to be seated, they watched as a group of A-Gays they’d seen at the concert earlier that night-Don McCleary, among them-was seated at a corner table. The councilman and his companion, meanwhile, were told that the kitchen was closed for the night.

The message? In Dallas, there is power. And then-on another level entirely-there is real power.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte