MUCH MORE THAN SIMPLY A PLACE NAME AND A NUMER-al, the Dallas Nine was a movement made up of a small group of Dallas painters whose seminal body of art works is regionalist art in the best sense- works that serve as description and definition of a particular time and place.

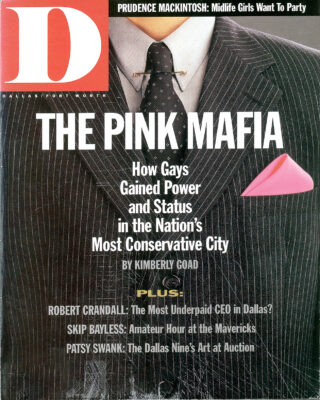

The work of the Dallas Nine and their circle goes in and out of fashion. It sells for less, then more money. At times major exhibitions are devoted to it. and at other times it is ignored. Now, many of the works of the Dallas Nine will be auctioned at the first Lone Star Regionalist Auction, at the McKinney Avenue Contemporary on Nov. 9.

The Dal las Nine members were, themselves, determined, apprehensive, derisive, loyal, fractious–and priceless. They were Dallas artists who made new art in a traditional era. They also taught, wrote, lectured and sometimes worked for a living in jobs totally unrelated to art. The period in which they created their art is generally defined by the Great Drought, the Great Depression and World War II, with its aftermath of expansion and contraction. Their passion was to put onto canvas what they saw and felt about this chaotic period. The group’s kindred colleagues included authors, architects, musicians, poets and journalists, answering in a way unique to Dallas the cultural unrest rising at that time throughout the country.

EARLY IN 1932 THE WORK OF A GROUP OF ARTISTS, NONE OF THEM yet 30 years old, made up an exhibition at the Fair Park Dallas Public Art Museum, titled “Nine Young Dallas Artists.” A review of this show in New York’s Art Digest called attention to the vitality and verve of the Dallas art scene and fixed the number as an identifying point of departure for a whole community of artists who had gathered-and were gathering-then to work in Dallas.

The artists in this show were Jerry Bywaters, John Douglass, Otis Dozier, Lloyd Goff. William Lester, Perry Nichols, Everett Spruce, Charles L. McCann and Buck Winn.

That particular circle grew or diminished and grew again with new faces over the next two decades. Other painters became part of the movement-Alexandre Hogue, Charles Bowling, H.O. Robertson. Merritt Mauzey, Florence McClung. Tom Stell, Russell Vernon Hunter, Don Vogel and sculptors Octavio Medellin, Dorothy Austin and Allie Tennant. Younger and later additions to the group included Ed Bearden, Barney Delabano, DeForest Judd and Dan Wingren. Works by some of these artists were seen in the recent Valley House gallery exhibition, “Texas Art of the ’50s and ’60s,” curated by its director, Kevin Vogel. During the *40s, the elder Vogel was the principal Dallas liaison with a group of younger Fort Worth artists interested in ideas and influences from outside the state.

“Nine” emerged as a number again only in 1935, when a group REMEMBERING THE DALLAS NINE

AS AN ART CRITIC FOR THE DALLAS MORN-ing News during the 1940s and as the wife of Dallas architect Arch Swank, who was himself a colleague of the design-concerned Dallas Nine painters, Patsy Swank came to know well both the Dallas and the Fort Worth artists and their work. Here, she recalls each artist:

JERRY BYWATERS: Lean. Tall. Natural leader, but could be scrappy. Wry humor. First a painter, then a critic, teacher, writer, collector, archivist, family man, defender of both artistic freedom and pragmatism. Said of the SMU archive/collection that bears his name: “We saved this stuff mainly as a reminder of what’s been done and what needed to be done.”

JOHN DOUGLASS: Painter and printmaker. Established the John Douglass Gallery in 1940, which had an important community life until well after his death.

OTIS DOZ1ER: From Forney to Dallas to the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center-as student then teacher-and back to Dallas, his hand and eye produced elemental form, and color to tremble the eyeballs. The results of the matchless collaboration between Dozier and his wife, Velma, an extraordinary designer of jewelry, can be seen in the Dozier Room at the Dallas Museum of Art. He said, “You have to start from where you are and hope to get to the universal.”

LLOYD GOFF: Quietly professorial Dallas native best known for murals, but whose work ranged from portraits to delightful illustrations for children’s books. Loved to paint the night sky and moon. Kept his Texas touch after he moved to New Mexico.

WILLIAM LESTER: Tall, lanky, soft-spoken painter born in Graham, Texas, whose imaginative realism had a “bone-dry paint effect” and “walls that shimmer like mirage” and reminded a New York Times critic of the poetry of Robert Frost. Chaired the University of Texas-Austin art department until retirement.

PERRY NICHOLS: When he attended the restoration party in 1986 for the murals he had painted in 949 for the Dallas Morning News building, he was as slender, sophisticated and acerb as ever. Best remembered for the clear, sharp, luminous pictures he did in his favorite medium of egg tempera.

EVERETT SPRUCE: Brought the Arkansas landscape with him to Texas-rabbit hunters, deer, rural schools and farm chores. Later became chair of the University of Texas-Austin art department.

CHARLES MCCANN: Exhibited in the Dallas Allied Arts Exhibitions of 1928 and 1932. Appointed assistant director of the Dallas Art Institute in 1932, but dropped from sight after the 1930s.

BUCK WINN: James Buchanan Winn went from a family land-grant farm in Celina. Texas, to be a prize winner in the 1929 Dallas Allied Arts Exhibition. He emerged as a moralist, then went into relief and ’”sculpture as part of architecture,” the design of an experimental airplane hangar, shell structure for one house, then new building research. The American Institute of Architects in 1974 named him a “professional associate.”

-Patsy Swank

of the artists-some old, some new, but adding up to nine-submitted a proposal for a Texas art component for the upcoming Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936. Their proposal was barely considered and instead, an imported artist, far more interested in grandiose symbols and familiar styles, was given the job. The local boys got to work with him, notably and thankfully, in the Hall of State. But still holding were the ages-old traditions of representational art-landscapes, mythology, aristocracy and formal still life, traditions the Dallas Nine were breaching, that had long since been broached in Europe and in the major arts centers of this country. But that ice had hardly cracked in Texas.

The atmosphere surrounding the Dallas Nine was not a “country boy” climate, though the original Dallas Nine were country boys in the sense that six of them were native Texans and the rest came from nearby states. But every one had studied at the New York Art Students League, or the Chicago Art Institute, or an institute of comparable importance, A number had traveled and studied, and some had lived, in Europe.

Their drive was to put emotion and new form into painting commonplace things. Looking backward from the end of this century it is hard for anyone to realize how revolutionary a position that was, or how difficult it was to hold. They painted and showed and (sometimes) sold, but that was only part of the work of these many-more-than-nine. They formed the activist Dallas Artists League and two printmaking associations to improve their skills and to arrange tours. They designed sets for the Dallas Little Theater. Concerned as they were with the design and look of the city, their colleagues were architects David R. Williams, O’Neil Ford and, later, my husband. Arch Swank, who were looking both to the Bauhaus and to native structures and old ways of building. Jerry Bywaters and Alexandre Hogue wrote for the Southwest Review, SMU’s nationally known “little” magazine.

The Dallas art community was supported by both newspapers, but particularly by The Dallas Morning News. The paper had had an art critic since 1926; Jerry By waters had been one of them. The News’ amusements editor (his term) John Rosenfield advised, scolded and generally helped the Nine far beyond the consistently incisive reviews and coverage he gave their activities.

The Nine knew how to have a good time. Their parties were famous, if rarely formal. Some of the Nine were included in the beautifully produced debutante parties that were the social events of those seasons, but for good cheer and heated discussion, the Very Elegant Thursday Afternoon Shrimp Club-once a week at the corner of Alice Street and Cedar Springs where free shrimp was served with a 25-cent beer-was the place to be.

World War II naturally curbed this vitality and liveliness. Some of these artists served in the armed forces, others in war production. The exodus to teaching positions would see the end of the broad and informal community life of which the elastic Nine was so much a part.

During the war. the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in Fair Park, of which Bywaters had become director in 1942. became almost a community center for exhibition, teaching, and music and dance concerts (despite the inoperable air conditioning). Inevitably the Dallas Nine and its circle moved in new directions, in their lives and in their work.

In 1984 RICK STEWART, THEN THE DALLAS MUSEum’s curator of American art and now director of Fort Worth’s Anion Carter Museum, produced the definitive retrospective exhibition of the Dallas Nine’s work, accompanied by his invaluable book Lone Star Regionalism-The Dallas Nine and Their Circle. Dr. Stewart quoted a Dallas Morning News critic who described “the arrival on the Texas scene of ’non-specific regionalists who have been busy painting away from the earth.’” He noted individual works of several of these painters as illustrating the development of a “non-specific regionalism” in the sense that “illusion and reality are beginning to be further de-emphasized. Yet it is still regionalism; instead of stressing subject, the artist is striving for raw sensibility.”

I was the Dallas Mornig News critic whom Dr. Stewart quoted, then three years out of college and two years into my first job. I had come to know well both the Dallas and the Fort Worth artists and their work. Asked to write an introduction to the gallery listing for the first New York exhibition of the tightly knit young Fort Worth group, I literally agonized over finding words that would clarify the different aspects of this word “regional.1’

With the museum’s postwar changes and its continued importance in the community, the Dallas Museum of Art as we now know it began to emerge. Jerry By waters continued to encourage and show Texas painters. Once Life magazine ran a great full-page photograph of Bywaters himself, straddled over a chair in a gallery of paintings by the one and only H. 0. ” Cowboy1’ Kelly. But he opened other avenues as well. There was an important school for young painters. There was an exhibition of the earlier works of Hans Hoffman, whose exploding colors and forms set off almost as much public controversy as did the bitter political scare hunts aimed at artists in the late ’50s. The city would not have weathered that terrible time as well without the training ground for new ideas and new forms in painting, and for the understanding and tolerance that was the legacy of the Dallas Nine and their circle.

The ’50s scourge was part of the reason for the birth of The Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts, from its inception on Ed and Frances Bearden’s back porch to broad popular and powerful individual support and the short but great years of Douglas MacAgy’s directorship. Without the early foundation of the Dallas Nine and their circle, the DMA constituency would have been less ready to accept and appreciate the superb contemporary collection that came to it from the Museum for Contemporary Arts when the two organizations were merged.

The Dallas Museum of An fortunately houses a fine cross sec-lion of the work of the Dallas Nine (10,12, 15?). The museum continues to grow and change to meet the needs of its community rather than succumbing to prevailing fashions. It remains, in addition to its other major attributes, a regional museum.

Regionalism is, after all. a movable feast, made up of works like those of the Dallas Nine, that illustrate time, place and history.

Related Articles

D CEO Events

Get Tickets Now: D CEO’s 2024 Women’s Leadership Symposium “Redefining Ambition”

The symposium, which will take place on June 13, will tackle how ambition takes various forms and paths for women leaders. Tickets are on sale now.

By D CEO Staff

Basketball

Watch Out, People. The Wings Had a Great Draft.

Rookie Jacy Sheldon will D up on Caitlin Clark in the team's one preseason game in Arlington.

By Dorothy Gentry

Local News

Leading Off (4/18/24)

Your Thursday Leading Off is tardy to the party, thanks to some technical difficulties.