“My bouse was…squeezed between two huge places… The one on the right was a colossal affair by any standard-;’/ was a factual imitationof some Hotel de Ville in Normandy, with a tower on one side, spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy, and a marble swimmingpool, and more than forty acres of lawn and garden. It was Gatsby’smansion “ -F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, THE GREAT GaTSBY

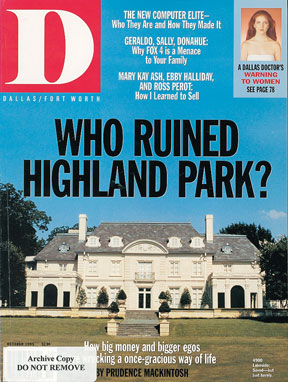

GATSBY MANSIONS HAVE BEEN POPPING UP FOR YEARS ALL over the Park Cities.

We have multi-columned brick houses, that could be college administration buildings or portentous libraries, standing what seems only an arm’s length from dwellings resembling, in style and square footage, Southern Methodist University sorority houses that, of course, manage to accommodate 35 acquisitive young women for three years of their lives.

We have Georgian nondescripts that wouldn’t be so offensive if they didn’t take over whole blocks like uniformed soldiers or stand forlornly like an excluded lanky adolescent in a prairie of snug, well lived-in, one-story, postwar bungalows.

We also have structures of no discernible architectural style with all manner of ornamental doodads pasted on, giving the house the appearance of a woman who has forgotten her mother’s admonition: “Earrings and bracelet or necklace, never all three.”

We have Southern plantation houses (sans plantation, of course), with unused double gallery porches snidely known as Taras near the Tollway.

Interspersed among these monumentalities, we have bungalow second-story “redo add-ons” that look, as one young architect observed, “like St. Bernards humping Chihuahuas.”

We also have just ugly.

I don’t know how to explain narrow two- or three-story arches swooping up above modest front doors that seem embarrassed by-all the fanfare. Perhaps these are the products of constant strife among husband and wife and builder resulting in an unfortunate compromise. Or maybe the homeowner just left for the Caribbean and told the builder, “Surprise me,”

None of the above would be so bad if we only had Gatsby’s 40 acres on which to display (or perhaps obscure) our wretched excess. But the little town of Highland Park is only 2.2 square miles. The average lot is approximately 12,500 square feet, usually only 50 feet wide. The average house being built here now is 6,000 to 7,000 square feet. (An original two-story Highland Park house, now on display at Old City Park, has about 2,000.)

Forty-four new houses went up in Highland Park last year, twice the number built in 1991, almost as many as were built in the speculative building frenzy of 1985. The relentless scrapping of old houses, dubbed “preowned” by the real estate agents, and the competitive scramble to build something bigger and grander and gaudier make us wonder if we’re losing not only our history, but also our eye for the human scale. “Just call it the outward and visible sign of the lack of inward and spiritual grace,” quipped a resident Episcopalian.

My family has lived in The Bubble for nearly a quarter of a century now, not long enough to be mistaken for original settlers, but certainly long enough to join in the lament over change that inevitably comes to old neighborhoods. “They’re just ruining the neighborhood,” I overhear a fellow resident say while picking through the bananas at the Village Tom Thumb, Granted, it’s hard to see how a town that houses its efficient city government in an original Spanish mission-styled building with red-tiled roof and that heralds spring with banks of azaleas and Icelandic poppies and fall with children scampering past a crossing guard who knows them by name to nearby schools still deemed excellent can be called ruined. Thoughtfully designed, excellent houses do get built here. Still, a freshly bulldozed lot sends a tremor of dread down the tree-shaded street.

When my husband and I were young and new to Dallas in 1969, we rented an apartment in Oak Lawn. We had the upstairs half of a postwar ( WWI) red brick duplex with thick stucco walls and 9-foot ceilings. For a mere $150 a month, we lived in the proximity of millionaires, and we often ended an evening out with a drive through Highland Park. With draperies drawn back and candles and chandeliers gleaming, these houses seemed charmingly hospitable, sophisticated, and elegant.

The young attorney and schoolteacher that we were then did not aspire to own one of these houses. We had no children and were unconcerned about school districts or taxes. We simply enjoyed the free evenings’ entertainment of imagining the interesting lives that must surely be led in such graceful and evocative surroundings. Although, with eventual familiarity, I discarded some of my stereotypes and romantic notions about the inhabitants of Armstrong Parkway, Bordeaux, Lakeside, and Beverly Drive, I did encounter in some of those fine old Highland Park houses people of unpretentious but exquisite taste, who lived comfortably and hospitably in homes that seemed natural extensions of their owners’ regard for excellence, refinement, propriety, civility, and restraint-all qualities that were rapidly being discarded by my generation.

After our first child was born, we found a Tudor cottage redo we could just barely afford in Highland Park, We lived unredone for several years with window-unit air conditioners and perilous steam radiators and floor furnaces. Early attic furniture kept us from going further into debt and spared us the opportunity to exercise our youthful bad taste. We enclosed a porch when the third baby was born, and when three growing sons made the walls reverberate in 1978, we knew it was time to move. The real estate agents touted my house as a “cute, spacious, airy Tudor,” but the most attractive features of the house were the intangibles. How do you place a value on a neighbor who welcomes you with cookies and a cutting from an African violet the previous owner of the house had brought to her years ago? My boys thought the big selling point was its lucrative location for lemonade stands and their “worm farm,” a low-lying area near our corner curb where water and mud collected to create an ever-fascinating earthworm haven.

We were not just selling a house, we were leaving a healthy mix of neighbors, diverse in ages, interests, and professions-a psychologist, an elementary teacher, a high school algebra teacher, a stockbroker, a Southern Methodist University professor, a retired salesman, a real estate agent, a box factor)’ owner, an airline pilot, a swimming teacher (with a pool), a doctor, a judge, a journalist, and a lawyer. It wasn’t exactly a melting pot, but it did mean that we had skills to share, The women were mostly at home during the day, so children had the lightly supervised run of three or four blocks, as well as the school playground at the end of our block. Like a Norman Rockwell painting come to life, rites of passage-the birth of a baby, a son returning from Vietnam, a daughter’s engagement, an 80th birthday, even the sadness of a divorce-were shared by the whole block.

Has any of this changed? More mothers work away from their homes now, leaving children to nannies and the maintenance of neighborly rituals to older residents. Also, the price tags on the property have been marked up. The house we bought in 1970 for $38,500 and sold eight years later for $135,000 has now been completely remodeled and sold for more than $600,000.1 wonder if higher lot values in the town will mean further stratification, narrowing the types of people who get to live here.

Despite its reputation for immutability, The Bubble has actually been recreating itself since its inception. In 1889 Henry Exall, the first land developer to get his hands on 1,326 acres of virtually treeless farmland four miles north of the growing city of Dallas, envisioned an exclusive enclave for wealthy families that he called Philadelphia Place. Exall put in gravel roads and dammed Turtle Creek, creating Exall Lake. Had the Panic of 1893 not forced him to sell off a large part of this acreage before a single house was built, the original architectural style in Highland Park might have been primarily Victorian.

John Armstrong, who bought the land from Exall with the proceeds from the sale of his meat-packing company, liked Exall’s idea of an exclusive park-like community. Instead of looking to Philadelphia for inspiration, however, he and his sons-in-law, Hugh Prather and Edgar Flippen, went to California to plan the community. They hired landscape architect Wilbur David Cook, the designer of Los Angeles’ Beverly Hills, where European eclectic architecture was all the rage. Cook set aside 20 percent of Highland Park for parks, and Prather planted fast-growing trees to give credence to his advertisement, “It’s 10 degrees cooler in Highland Park.”

The Dallas Country Club moved from its Oak Lawn setting to Highland Park in 1912, building a grand Tudor structure for its first clubhouse. The mansions along Exall Lake and Turtle Creek were built between 1907 and 1910. Early architects and their clients were educated and well-traveled people who brought in European craftsmen to create tiled fountains, stained-glass windows, or carved stonework to complement the Italianate or Spanish styles they desired, Simpler Mediterranean and classic Greek revival as well as graceful frame or brick houses (sometimes called American Foursquare or Prairie style) spread down Gillon, Lexington, Euclid, Harvard, and Miramar toward the Knox Street Trolley and along Drexel and St. John’s near Hackberry Creek.

Most of the lots in Highland Park east of Preston Road were drawn narrow and very deep (approximately 60 by 190) to allow backyard space for servants quarters as well as the early 20th-century homeowners chickens, milk cow, and cistern. If only we could reverse chose dimensions!

The town developed west of Preston Road in the late ’20s. Fewer people were keeping chickens so lots were not drawn as deep as they had been in Old Highland Park. Alleys were also deleted from the plan because they were perceived to be playgrounds for live-in servants on their Saturday night revelries.

The Great Depression hit just as this part of the town was getting started. “Politically conservative folks in Highland Park probably don’t like to hear it,” says Hugh Prather Jr., son of one of the original developers, ’’but there wouldn’t have been a Highland Park if it hadn’t been for FDR and the FHA loans. People who would have been renters the rest of their lives could suddenly afford to buy a home with the revolutionary new 25- to 30-year mortgages. That’s how we kept building in the ’30s.”

Highland Park began filling in with houses of all sizes. Whole blocks of one-story bungalows appeared. In addition to those with inherited wealth and well-to-do professionals, the Park Cities would also be populated with “comfortable” middle-class families. “We gave ’em so much for their money in those days,” says Prather, who by that time was assisting his father in the sale of Highland Park real estate. “You got a mighty well built house in the ’30s for five or six thousand dollars.”

Dallas architects and builders, not yet under the sway of Walter Gropius and the German Bauhaus architectural movement (so wittily skewered by Tom Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House), willingly built Colonial Revival, Tudor, Spanish, and French styled houses on a single block, creating an interesting rhythm and surprising harmony. The builders had to passmuster with Flippen and Prather’s “architectural review board,” which actually consisted of one young architect, Harwood K. Smith, to whom they gave free office space in their innovative new shopping center, Highland Park Village. Smith, who went on to win fame as a builder of commercial properties, says, “I didn’t do much. Prather would bring me a plan that looked odd or out of place to him, If it didn’t seem to fit with the other houses on the block, I’d nix it. We were just coming out of the Depression. Most architects knew what they had to build to sell, so we didn’t have much maverick building.” Architect David Williams, O’Neill Ford’s mentor, was designing period houses in those days. Even Charles Dilbeck’s rustic and whimsical hybrid creations were always built in scale with more traditional houses on the street. The grand mansions and boulevards gave the neighborhood romance, and the more modest struccures bespoke a serene stability.

In the eight years that we lived in our serenely stable part of Highland Park, our little house with the porch enclosed quadrupled in value. With our profits, we were able to move to a bigger, although older (1927) house a few blocks away. It was the beginning of an era of real estate speculation that some point to as the ruination of the neighborhood.

“I don’t know who all these new people are who have moved in here, but I wish they hadn’t. ’Nouveaux riches’ with no taste are what is destroying the neighborhood, but I guess we can’t say that,” says one resident who has lived here for most of her 75 years. “I wish they would get their kids through the school and get out of here.” Amused by her own snobbery, she advises me that there are still residents of Highland Park who haven’t recovered from the GI Bill, which sent “all those people who didn’t belong there” to SMU after World War II.

Nouveaux riches are, of course, nothing new in The Bubble. Very few families here can trace their lineage to first families of Virginia or Spanish land grants. Most family fortunes were made in this century on small grocery businesses, cotton, land investments, banking, and oil. “Showboating was frowned on,” says a friend who grew up here in the ’50s. “We knew who had a lot of money in the ’50s and ’60s, but kids didn’t drive Porsches to the high school.”

” Frowning” had either stopped or was clearly not enough to deter the greed and conspicuous consumption of the ’80s, when high rollers fearing bankruptcy attempted to create financial safety nets by stuffing as much money as they could into their creditor-proof homesteads. “Asset protection’’ is the legal term. The safety nets did not always hold, but the penchant for relentless acquisition is still with us, as are the opulent “bigger is better” stuffed houses.

Can we blame City Hall for failure to rein in some of these steroidal structures? A plaque in the council chambers of Highland Park Town Hall reads:

“A haven for home and fireside-undisturbed by conflict of commercial or political interests. The function of government in Highland Park is protection of the home. Citizens who cherish their homes will vigilantly preserve their heritage of self government.”

I don’t know what that means except that we like our attentive police, and we aren’t about to let Dallas annex us. As for conflict of interest, city coffers do benefit from the increased tax money gleaned from houses with greater square footage. Highland Park Town Administrator George Patterson admits that we need it. Shoring up infrastructure to comply with federal mandates like the Clean Water Act takes a big bite out of the budget. When I asked about the increased scale of the houses still being constructed, he grinned and said, “You’ll get used to it.” He also assured me that no one is violating the city’s building codes. “People talk about zero-lot-line houses in Highland Park, but there are no houses covering more than 40 percent of their lots unless the area is zoned for townhouses.” The amount of lot square footage a house can cover was upped from 35 percent to 40 percent in 1983, according to Patterson, “because some of our elderly citizens needed a downstairs bedroom.”

That sounds reasonable enough, but a 5 percent increase can’t explain why these two-story houses look so out of scale with the rest of a two-story block. Patterson says it is because people now are building to the limit of the codes. Apparently the building codes always permitted houses as high and wide as these, but people just didn’t require 10- or 14-foot ceilings on every floor when these older houses were built. Buyers who pay a premium for a lot here apparently feel they’ve been snookered if they don’t use every inch allowed for the house. Those intangibles-the worm farms, block parties, safe streets for walking or jogging, a cozy little library, neighbors to pick up your newspapers, being within walking distance of free concerts at SMU, and mallards landing on Exall Lake-don’t seem to figure in the real value.

Aesthetic considerations are not the only reason the old houses of Highland Park have more space between them. Building inspector Paul Vermeer reminds me that air conditioning has had as much influence on architecture in the Park Cities as any changes in building codes. Houses without air conditioning had to be built farther apart to allow cross ventilation and a measure of privacy when windows were open all summer. With air conditioning came houses with unat tractive blank brick sides, or worse, houses with one mean little side window off center somewhere on the second story. It also turned porches into dec orative appendages rather than places to sit with neighbors while kids played “spotlight” or chased fireflies on sum mer evenings.

The municipal governments of both Highland Park and University Parkhavenever had architectural review boards and all original deed restrictions have expired. The clamor for “taste police” in the Park Cities is largely tongue in cheek. Besides, whose taste would we trust? This is not Santa Fe with a single indigenous architectural heritage to preserve. Architects and builders alike find Highland Park’s building codes among the most restrictive anywhere. The town prides itself on still requiring metal conduit for all electrical wiring, a precaution even University Park discarded years ago, Variances, granted by the Board of Adjustment (members of which are appointed by the city council), are hard to come by.

Architects actually complain that the restrictive codes only encourage the building of unimaginative, boxy houses. Taking the city ordinance allotment envelope and filling it up with a formula house makes good financial sense to speculative builders. “It is certainly easier and less expensive to demolish an old house and rebuild than to ’retrofit’ an old house with the amenities most people require today, ” says longtime Park Cities real estate appraiser D.W, Skelton.

Poorly trained architects who abdicate their responsibility to advise clients on the neighborhood impact of their building design surely deserve some of the blame for what is happening here. A homeowner shouldn’t have to apologize to the neighbors: “I didn ’t know it was going to be so big.”

If you’re lookingfor villains in this socio-architectural drama, speculative builders are an easy target in the Park Cities. Houses built solely for investment purposes usually have a fungible, unloved look to them. Some look as if they’ve been dropped in with a loud thud by helicopter. I walked through one in University Park recently and asked the builder about the involvement of architects in designing these houses. “We have architects for the general plan. Then, we vary the styles a little depending on where we’re building. We add extra molding here in the Park Cities. We’ve had a lot of success with this particular house in Piano.”

Higher lot values have kept spec building to a minimum in Highland Park in recent years, although the spate of construction in 1985 left some streets totally transformed. University Park has been hard hit. Like anybody who needs to make a buck, speculative builders pop up where opportunity arises. Lower lot values on streets with one-story bungalows make these cozy neighborhoods especially vulnerable. “My block looks like a ransom note,” laments an Amherst resident who has turned his small bungalow into an architectural gem. The “North Dallas Special” with its pretentious, beefy cornerstones and its gables and dormers, towering and peering menacingly into the entire neighborhood s backyards, is enough to make the block parties fizzle.

Retired Highland Park folks, shaped by the austerity of the Great Depression and WWII, will tell you right away that “the culprit is too much money and no sense.” They offer sharp and often accurate observations on how the appearance and ambiance of the neighborhood is affected by the lifestyles of the affluent young. “We have some real airheads on our block,” one retiree says. “They pay entirely too much for these houses, and then don’t even bother to go and protest their tax evaluations.” These older residents are exasperated by younger newcomers’ thin knowledge of quality construction, i.e. the acceptance of Home Depot plug-in windows and glossily painted cabinets made from fiber board or pressed paper in new houses with half-million dollar price tags.

They also notice the increased transience in their neighborhoods. Houses in Highland Park used to bear family names because people stayed put. According to the town’s Water Department, the move in/move out rate has increased. Fifteen years ago, the rate was about 12 per month; now, it is not unusual to have 50.

Finally, the longtime residents complain about their younger neighbors’ dependence on services that keep their streets littered with trucks. “If it’s not Domino’s Pizza pulling up because they rarely cook in their gourmet kitchen, it’s the yard crew with those dreadful leaf blowers, the landscaper replacing their ’seasonal color,’ the personal trainer, the pool service, or the pet groomer. Don’t people even know how to wash a dog anymore?”

Real estate agents confirm that the new buyers in the Park Cities are indeed looking for instant gratification. Only the youngest and least affluent will accept “charm” as a reason to buy a house. (A “charming” three bedroom/two bath house, especially if it is on a block with new construction, is usually priced as a tear-down for lot value, often $275,000 to $300,000 depending on the street location.)

“Affluent young, two-career couples with more money than time are not looking for redos,” a real estate agent says. “These couples want all the amenities: four bedrooms, the “his and hers” bathrooms, the enormous closets, the big kitchen with spacious den attached, a master suite with a small coffee bar, an exercise room, a media center, and separate quarters for the live-in nanny or maid, The newer, the better.”

Such couples don’t want the maintenance an old house and a yard require. Though they pay lip service to the neighborliness of Highland Park, exhausting jobs and the irritation of a Central Expressway commute can contribute to a “drawbridge” mentality exacerbated by alley entry garages. Knowing the neighbors may not be a high priority.

But it’s not just the young professionals who are building fortresses and contributing to the sprawl. “With age comes money, not wisdom,” says one wryly architect commenting on the big house phenomenon. “People who have reached a pinnacle of success in midlife,” he muses, “sometimes become romantic old fools. They want to see themselves as Scottish barons or country squires.” Blame the enormous houses, the Taras and castles, on Gone With the Wind or “Masterpiece Theater.” People like the idea of descending into their wine cellars or propping their feet up in the “keeping room.” It is living one’s life on a theatrical stage set.

Perhaps bored women also contribute to the overbuilding in Highland Park. “Adding a wing to the house or having another child has long been a palliative for women of my generation who are victims of their husbands’ financial success,” says a former Junior League member. The husband wants his wife to have something to do. so he acquiesces to yet another move. Building and redoing bigger and better houses becomes her career. She feels powerful when she speaks of “my carpenter, my plumbers, my painters.” One woman is rumored to have added a wing just so she could have her Bible study group meet at her house.

In the midst of so much disturbing change, it’s refreshing to visit a home that does not depend on one-upmanship for its essential character. In a house I visited several weeks ago. each room seemed perfectly scaled for its purpose-a real library, not a color-coordinated one; a dining room where two people sit down to dinner every evening; a comfortable living room with a piano, which she actually plays; an area for listening to a prodigious collection of well-cared-for opera records. A small buzz fan placed unapologetically on the living room floor while we talked helped keep the electric bill within reason. They spoke of the increased difficulty of finding comparable small houses with which to fight increases in their tax appraisals. But 1 had come to hear a horror story of how neighborhood civility is tested by boorish, arrogant building.

Any sort of building project inconveniences next-door neighbors. A lumber truck backing down my narrow driveway during our own remodeling project deposited its load in my neighbor’s lovely breakfast room bay window. This particular couple, who have endured the razing of one house next door and the building of its larger replacement, have war stories and altered lives to show for their experience. “You know you’re in trouble,” he said, “when the new neighbor’s bulldozer sends a brick chimney crashing through your dining room windows, when the new owner immediately challenges the frontage setback, or asks to take down your fence while the building is going on.” Thoughtlessly placed air conditioning compressors turned their pleasant little deck into a noisy inferno. The height of the humongous new house kept their chimney from drawing. Carelessly angled downspouts forced them to defend their property with an expensive retaining wall.

These polite residents of Highland Park deplore confrontations with their neighbors and feel frustrated when the city refuses to intervene in their behalf in neighborhood disputes, but city ordinances seem toothless in the face of a builder who says, “Don’t mess with me. You’ll lose.” A privacy hedge removes a treasured view from a dining room window. Heat generated by a 9-foot stone wall kills most of a neighbor’s carefully cultivated perennials. Houses and people in Highland Park used to mind their manners.

Other neighborhoods of comparable vintage, notably Lakewood andGreenway Parks, do not seem to be suffering these building woes or losing their architectural character as fast as the Park Cities. “They don’t have the school magnet to draw so many new people,” a real estate agent reminds me. The perceived collapse of public schools in North Dallas and the filling up of private schools are making people desperate to get into the Park Cities. The Highland Park Independent School District enrolled 5,3 16 students this year, the largest number since ) 968 when even,’ grade-bulged with baby boomers. A slab foundation, spec built house may be what these new residents had elsewhere, and it’s certainly good enough for the seven or eight years they need to be here.

The other major drawing card, of course, is security, Highland Park’s 911 response time is two minutes maximum. Slightly apocrypha] stories of the precautions taken by our police and fire departments abound. One friend recalls the time her daughter and her teenage friends, home alone one afternoon after a soccer game, accidentally set the oven to broil instead of bake and set tire to the pizza. Moments later, sirens were screaming toward Normandy Street. Ax-wielding yellow-slickered firemen appeared at the back door with hoses ready. Finding no fire, they set up giant fans to blow the smoke out the back door. The mother returned to a peaceful and perfectly restored kitchen.

In many ways, the Park Cities are victims of their own success. The schools, the security, and the good resale value of the property make the neighborhoods a first stop for out-of-state corporate executives slated for relocation. (Believe it or not, Highland Park is considered an easy commute to Las Colinas! Preserving or creating harmonious architecture may not be a priority. “Unless they’ve lived in a neighborhood like this before, they are just blown away by what you don’t get,” says a local real estate agent. “It’s hard to sell them on sidewalks and a terrific Fourth of July Parade, which are two important things this neighborhood offers.” These people are looking for three-car garages.

Efforts by the Park Cities Historical Society to raise neighborhood awareness of distinguished period homes in the town are laudable, though perhaps too little, too late. They have recorded addresses and photographed every house in the neighborhood built prior to 1940. They have also given historic landmark medallions to several sites, including the magnificent pecan tree on Armstrong Parkway that is lighted each Christmas and the Daniels Family Cemetery, as well as 30 or more houses considered architecturally or historically significant, These designations, however, carry no authority. Some of the identified homes have already been razed. It’s hard for me to imagine not wanting a house with a story behind it. Surely a third-floor ballroom could be put to some contemporary use. But a friend who has also lived in old houses reminds me, “Prudence, some people really don’t want to know the Roto-Rooter man as well as we do.”

Architect Harwood Smith, who has seen Highland Park change since the ’30s, surprised me with his pragmatic and unsentimental view of recent building in the neighborhood. “Highland Park will be glad it has these big new houses. The town is old now and replacing its water and sewage systems and maintaining its old streets will be increasingly expensive. These big houses will provide the necessary tax revenue. Houses, especially the ones that are well built with all of the luxury amenities that people seem to want today, will continue to attract new people. We did the best we could in the ’30s with what we had. Some of the materials are actually better now. Even the grand old houses in the neighborhood didn’t have the elegance of space that houses have today, especially upstairs. People are not drawn to Highland Park by tiny bathrooms and three-by-two closets.”

Another architect, Frank Welch, known for designing houses that speak with a pleasant Texas accent, is optimistic that the pendulum will eventually swing, that people will tire of living in big houses that bear no relation to their essential spatial needs or their roots. Dallas Morning News architectural critic David Dillon wrote a year ago that a “small is beautiful” movement is emerging in other parts of the country.

I hope they’re right. In the meantime, I suppose we can always plant more trees.

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman