It’s an emotional topic, chocked with enough suspense and intrigue to keep the phone hanks filled on the radio talk shows, E-mail messages hurtled through cyberspace, and cocktail chatter at society balls and charity fund-raisers cranked up to a fever pitch. It’s a subject to which enough newsprint will be devoted in the next three months to obliterate a small pine forest in East Texas. It’s more urgent than whether George W. Bush, in the Texas gubernatorial race, can oust incumbent Ann Richards.

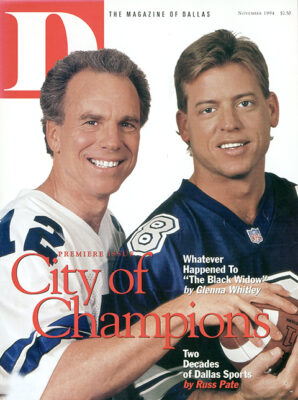

It’s simply this: Can the Dallas Cowboys win a third consecutive Super Bowl championship? To do so would be precedent-setting, a feat no professional football team, including the Pittsburgh Steelers or San Francisco 49ers (or even Dallas in its first generation of greatness in the 1970s), has accomplished.

The topic takes on added intensity because of events that unexpectedly unfolded at Valley Ranch last March, long before the 1994 NFL seasons first whistle blew and the first anterior cruciate ligament blew out; when Coach Jimmy Johnson departed suddenly to a fishing boat in the Florida Keys, after a nasty, ego-tilled showdown with team owner Jerry Jones, and brash Barry Switzer, the longtime Oklahoma University head coach slid into the saddle (or, rather, hotseat) as Dallas’ trail boss.

How Switzer motivates and manipulates the Cowboys players’ talent and emotions could ultimately have more to do with the team’s success in its quest to make pro football history-and the subsequent mood in North Texas during the winter and spring of 1995-than whether the starting lineup can offset the loss of such veterans as Ken Norton Jr., Tony Casillas, Thomas Everett and placekicking ace Eddie Murray. Perhaps only the health of quarterback Troy Aikman and running back Emmitt Smith looms as large in the Cowboys’ outlook as Coach Switzer’s performance.

“The coaching deal will he the lead story in Dallas. If Switzer’s not successful right off the bat, that will he the whole focus,” says David Casstevens, a former Dallas sportswriter and now the lead sports columnist for the Arizona Republic who covers the Cowboys’ emerging division rival, the Arizona Cardinals. “That’s true for any first-year coach, hut especially in that situation, where Switzer’s trying to follow a tough [jimmy Johnson’s] act and match what that act accomplished.”

Meanwhile, fervid football fans will follow each new Cowboys development with a zeal and passion generally reserved for cultists or TV soap opera addicts. No plot twist is too small, no hangnail too insignificant, for in-depth discussion and analysis.

“People generally have a strong desire for affiliation,”says Dr. Deborah Graham, a sports psychologist in Boerne, Texas who counsels professional athletes, “We want a cause, or purpose, in our lives, and some people in Dallas find that in sports. People who follow a team like the Dallas Cowboys get involved in every facet, from learning the players’ names and numbers to wanting to know about their personal lives. In a way, it gives them a sense of identity.

“Sports enlivens people’s lives,” says Dr. Graham. “They like the camaraderie, the shared experience. They enjoy being involved in the same emotional outlet. There’s a sense of community, of family, among sports fans.”

The Cowboys, as they have for 30 years, dominate the city’s sports agenda. It’s an agenda that in some ways overshadows other concerns competing for citizens’ attention-such matters as public education, domestic violence, race relations, mass transit, health care, homelessness, and issues associated with urban life in late 20th century America.

The area’s other professional sports franchises-baseball’s Texas Rangers, basketball’s Dallas Mavericks, ice hockey’s Dallas Stars, soccer’s Dallas Sidekicks-muscle their way into the limelight during their respective seasons, enjoying moments atop the sports section and leading off the nightly TV sportscasts. With icons of their own, from Rangers’ sluggers Jose Canseco and Will Clark to Mavericks’ slam-dunk-ers Jimmy Jackson and Jamal Mashburn to Stars’ goal scorers Mike Modano and Russ Courtnall to Sidekicks’ powerkickers Tatu and David Doyle, these teams offer enough star power and sex appeal to grab fans’ interest and imagination.

But the marquee name, the top banana of Dallas sports was, is, and will, for the foreseeable future, be the Dallas Cowboys. The Cowboys represent the city’s most visible export and its best public relations vehicle. In today’s global village dominated by satellite dishes and media intensity, the team probably has become the most recognized symbol of Texas since the six-shooter or 10-gallon hat.

The Cowboys have won four Super Bowl championships, including the past two. Their players and front office executives sport championship rings so outsized and outrageous, so utterly and typically Texan (albeit conceived by an Arkans-awyer), as to make the late Richard Burton’s wedding gift to Elizabeth Taylor look like it came from a gum machine. More than agriculture, aviation, electronics or oil, more than semiconductors or microchips, even more than the occasional maverick billionaire who makes his way onto the front page of The New York Times, the Cowboys have created and nurtured this city’s enduring image: City of Champions.

VERNE LUNDQUIST, THE sports anchor at WFAA-TV (Channel 8) in Dallas from 1967 to 1982 and now a leading talent with CBS Sports, vividly recalls the Cowboys’ rise to prominence. As the longtime voice for the Cowboys’ radio network, Lundquist witnessed how the franchise entered the city’s collective consciousness. “When the Cowboys began their ascendancy in the late 1960s, their success helped, in a great way, to erase the stigma associated with the Kennedy assassination,” Lundquist says. “The team gave all of us a reason to feel better about ourselves. The Cowboys’ success in the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s became a source of civic pride that all of us could share. I think one thing sports teams create for their fans is a communal sense of pride.

Pride in Dallas sports has been restored, thanks to the Cowboys. The wounds have been licked and the tucked tails lifted. After reeling in the late 1980s, the twilight of the Tom Landry-Tex Schramm era and the dawning of the Jerry Jones-Jimmy Johnson era, the Dallas Cowboys’ fortunes dramatically improved. Perhaps coinci-dentally, perhaps not, so did Dallas’ over-baked, overbuilt, overspeculated economy. The chest-beating pride-some would say arrogance-for which Cowboys fans are famous resurfaced in the early 1990s after Dallas had stockpiled draft choices and acquired rare talents like Aikman, Smith and Michael Irvin. By initiating year-round training, conducting a seemingly endless number of mini-camps, and staging summer camp in the broiling summer heat at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Dallas simply outworked the opposition.

Only this time around in titletown, it’s a new ball game. The players are different and so are the fans. “I credit the success of the new ownership and leadership in appealing to a different component of the city,” says Lundquist. “It’s a younger crowd, a more enthusiastic crowd, than in previous years. I have the sense that Jerry Jones and his people have made a concerted effort to attract the youthful and blue collar segments of the population. Where in the past, the Cowboys were more closely identified with the Dallas business community. They were part of the city’s establishment.”

So much so that fans at Texas Stadium were often loath to be demonstrative or to rock the (open) rooftop with raucous cheering, lest they ruffle the delicate sensibilities of fellow bondholders in the adjoining seats and be labeled outsiders. In the status-conscious Dallas of the 1970s and 1980s, being cast as an outsider, or nonconformist, represented a career-limiting move for aspiring executives.

The Dallas establishment has been dismantled, however, changed inexorably by the relocation of corporate headquarters that have brought to North Texas new residents unaware of or unconcerned with the mores and conventions of an arch-conservative city. “The whole composition of the city has changed since the days of the single, monolith Dallas Citizens Council that ran the city and made all the major decisions, The city has been fractured into 14:1 districts, and it’s more multi-ethnic and multi-cultured than ever before,” says Dr. Don Beck, codirector for the National Values Center in Denton and a professor of social psychology.

“Dallas has become a polyglot city and as a result, sports support is different. The fans at Texas Stadium are wilder now, not as reserved as when the seats were occupied by the successful and elite. It’s a much more diverse group,” says Dr, Beck. “In addition, sports now is less a private toy and more the egalitarian glue that holds the city together. Sports is a common rallying point for such a diverse city as Dallas.”

The changes are readily observable and audible. Steve Hollahaugh, an Irving resident who worked sideline security during Cowboys games from 1980 to 1991 and still attends several home games each season, witnessed the transformation. “There are more loyal fans, more average people, in the stands at Texas Stadium now than in the years when the Cowboys games were more a social scene and the crowd, especiaily women, came decked out in their finest clothes. Now you see younger crowds who are more involved in the game than with being seen and you see more tans wearing Cowboys jerseys and sweatshirts, and with their faces painted in Cowboys colors. You didn’t see too much of that in the 1980s.”

Hollabaugh says an impetus for enthusiasm comes from the Cowboys themselves. “The current players are much more involved with the fans than players were in the Tom Landry era. They’re more likely to acknowledge the fans, waving at them, pointing to them, firing them up. The fans, as a result, feel closer to the game and closer to the players. The games are more fun than they’ve ever been, and a lot louder.”

Championship-caliber play combined with raucous enthusiasm have produced pure gold. Financial World magazine earlier this year ranked the Dallas Cowboys as the most lucrative of the 107 franchises in American professional sports, estimating the team’s market value at $190 million. That’s some $50 million more than Jerry Jones paid for the Cowboys in 1989, not a bad return on the Arkansas oilman’s investment. Jones, never prone to understatement, is quick to call it the “most visible sports franchise in the world.”

That football highlights the landscape of Dallas sports should come as no surprise. As Dr. Beck explains, the game is an integral part of Texas culture. “In many small towns across the state, football is a rite of passage for young men, conveyed under the Friday night lights. It’s the one activity in which the whole town engages and, as such, becomes a source of identity and pride.”

Dr. Graham also experienced the same phenomenon while growing up in the South Texas town of Sabinal, 60 miles west of San Antonio. “The whole town rallies around football with a single purpose and cause. It’s the focal point of the community. You see the same thing in Midwestern states with basketball. In Texas, the farmers line up against the fence to watch the high school games, reliving their own experiences.” With the urbanization of Texas during the past generation, many countrified Texans brought to their new homes in the city and suburbs the habit, or rit-ual, of watching high school football games on Friday night. And Dallas Cowboys games on Sunday afternoon.

Moreover, notes Dr. Beck, games like football and basketball mesh well with the chaotic nature of today’s society. “A sport like baseball is all about tradition, mom and apple-pie, the Puritan work ethic. The psychological DNA of the game is based on order and structure. It appeals to an engineering-type of mind. At the other end of the spectrum is basketball, with its constant flow and motion. Baseball is order, basketball is chaos. Football falls somewhere in-between on the order/chaos scale.”

Another part of football’s wide appeal, noted Dr. Beck, is how the game accommodates all range of athletes. “Football is the one game that allows people of different sizes to play together. You have the tanks, or giants, or hippos, slow-moving powerful forces colliding up front. You have the diversity of the wideouts, who move with the grace and beauty of swans. Where else would you see the hippos playing the same game with the swans?”

Besides the physical diversity, the game offers its rabid followers a mental component that many find absorbing. “Football also offers a start-and-stop effect that appeals to strategic thinkers and those who would like to design a strategy for a particular play,” said Dr. Beck. “It’s not free flowing. There’s a mental appeal that comes from asking ’What play should they call next? Should it be a run? A deep pass?”

Dallas, with its legion of lawyers, MBAs and chipheads, minds cultivated to perform critical analysis, weigh alternatives, and create scenarios, has no shortage of strategic thinkers. And, by extension, armchair quarterbacks.

Nye Lavelle, a Dallas-based sports marketing consultant and futurist, perhaps best known for documenting the popularity of figure skating in America and predicting its emergence as the marquee venue of the Winter Olympics long before the Tonya Harding/Nancy Kerrigan incident, says that Dallasites’ interest in sports manifests itself in other behavior.

Like working out. “Dallas is a city where people are concerned about their looks,” says Lavelle. “Research shows conclusively that residents here tend to be fashion conscious and fitness conscious. If there’s one city that puts a premium on physical appearance, which is reflected in high amounts of activity in participatory sports like running, cycling, rollerblading and working out, it’s Dallas. We take care of ourselves much more than people in other major cities.”

Lavelle expects to complete city-by-city research this fall that documents how sports fans in Dallas differ from those in cities like Fort Worth, Little Rock, Austin or San Antonio. To date, he says, such sports research has been national in scope. But his interpretation of existing data, for example, suggests that soccer, despite its resounding success with the 1994 World Cup, will remain a tough sell in the United States.

“It’s a psychological, culture thing,” he said. “Soccer is a cerebral, slow-building game. It’s very European, where you build for the big moment. The American culture is based more on instant gratification. We want action, adventure and speed.” Small wonder, then, that professional football has supplanted baseball as the nation’s favorite sport. Or that the Super Bowl is now more popular than the World Series. Or that professional ice hockey, once thought to have limited appeal outside of northern, cold-weather areas, has made dramatic inroads into the Sunbelt, including Dallas.

“The fans in Dallas like the fast pace and hard hitting in our game,” says Jeff Cogen, vice president of advertising and promotions for the Dallas Stars. “They also like the use of music, the video screen, the lasers. Our product is more than just turning up the house lights and dropping the puck, it’s a full show. We give our fans a total entertainment experience, driveway to driveway, if you will.”

A general lack of understanding of the game’s strategy and nuances didn’t deter Dallas fans from enthusiastically embracing the NHL. Attendance at Stars’ games last year averaged 15,000, far exceeding management’s expectations. While the Dallas Mavericks suffered through a second straight season of near-record futility, the Stars filled an important role for the city as winter winners.

According to Lavelle, women represent the next growth area for professional sports. “Forty-five percent of the NFL’s new fans are women. Seventy percent of the NBAs new tans are women,” he said. “It’s a difference of attitudes and perceptions. It used to be the prevailing attitude that sports weren’t for women. Sports weren’t feminine, and if you played them you built up muscles, which wasn’t considered ladylike. Now young girls-and young men-want to build muscles. They want to be fit. They’re working out in the gym and health club side by side. The involvement of women has tremendous implications for sports in terms of game attendance, TV viewership and participation.”

THE SPELL THAT SPORTS holds on Dallas is unmistakable. The signs are so clear Mr. Magoo could see them on a misty morning. For example, the nation’s most detailed, well-rounded, agate-filled, married-to-minutia sports section appears daily in The Dallas Morning News. A TV sportscaster, Channel 8’s Dale Hansen- who covers the Cowboys as intensely as C-SPAN covers politics-reportedly commands an annual salary of more than $300,000. Skip Bayless, a talented, controversial sportswriter and author, cranks out columns for “The Insider,” a weekday sports fax published in Dallas for sports nuts who, amazingly enough, can’t get their fill of sports news and opinion through local and national media.

Local TV and radio programming is packed with shows devoted to the Dallas Cowboys. At last count, more than two dozen Dallas players had daily or weekly shows airing during the week. “I don’t know how they can continue to have all these shows and all these callers. I don’t know where the interest level comes from,” says Troy Aikman, who joined the fray this season as co-host of Pat Summerall’s show on Channel 33. “But you look at the ratings and they’re all good. It really wakes you up and makes you real-ize this really is important to these people.

“Generally speaking, I enjoy playing in a city where people care so much about their football,” says Aikman. “It’s enjoyable tor me to go out and play on Sundays knowing that you’re playing for an entire city, if not an entire state. It’s very satisfying.”

Maybe the most remarkable thing about Dallas’ all-sports talk radio station, KTCK-AM, is that its debut didn’t come long before last January, just in time tor the Cowboys’ second straight Super Bowl championship. People here have been talking nonstop about sports since the heyday of Doak Walker. Or Don Meredith.

That makes sense, though, because Dallas’ sports teams, especially the Cowboys, are the city’s signature. Other cities have their calling cards, their raison d’être. Los Angeles has its movie industry, New York has its arts, culture and financial district, Washington has its gridlock (er, power and influence), Orlando has its tourism, San Francisco has its food and wine, Memphis has its blues, New Orleans has its jazz.

But save for shopping-Dallas did, after all, give the world Neiman Marcus and the Horchow catalog, while raising the suburban mall to an art form-there’s precious little to separate Dallas from the pack, to give it distinction on the national scale. Other than its sports teams.

“People generally can be classified in three types,” says Dr. Graham, “competitors, participants, and spectators. By far the largest of these groups is spectators. Either they haven’t had the time or opportunity to play sports, or they don’t have the physical skills. But they do have the dream.”

With the Dallas Cowboys going for Super Bowl history, to the accompanying roar of approval from a young, energized Texas Stadium crowd-and with the Dallas Mavericks, Dallas Stars, Texas Rangers and Dallas Sidekicks chasing glory of their own-that dream is alive and well and living in Dallas.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.