THE CARD TABLE IS COVERED WITH A pretty tablecloth; atop it sits an IBM computer, the monitor glowing a luminous blue. Wearing her “uniform”-sweat pants and a hand-painted T-shirt-Janet Holley punches a button and watches as the printer begins chattering. Slowly, page after page, it spurts out a copy of the journal she’s kept for more than a year, ajournai she knows may be evidence in a murder trial someday.

Nearby, the king-size bed is covered with a new, pink and green flowered comforter. Janet bought the comforter, matching dust ruffle and pillow shams through a mailorder catalog last August. It’s now Easter, and she just found the time to paint the room pink and dig the linens out of the box.

Decorating her house used to be one of her favorite activities. Janet would spend hours at craft shows, looking for quilts and country knickknacks to occupy special niches in her small, immaculate home, in a neighborhood so new that few of the trees are taller than her husband, James. Dalmatians and fire trucks adorn her 2-year-old son’s bedroom; her 10-year-old daughter’s room is pink and frilly. Janet’s attention to detail extends to the exterior of the Holley residence in Sachse, a town north of Garland; her mailbox looks like a little blue bam.

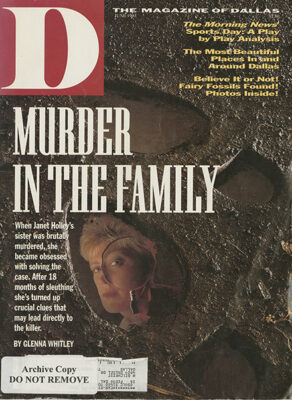

But in the last 18 months, there’s been no time for decorating. No time for the Garland Junior League or the PTA. No time for anything but her crusade. Since the day her sister, Sandy Dial, was found murdered. Janet Holley has talked and thought of little else.

She still works during the day, cleaning houses for a handful of longtime clients. But she wears a pager so that no matter where she is, Texas Ranger Don Anderson can contact her.

Most nights, when her children are finally in bed, Janet sits down at the card table, turns on the computer and begins to type. The IBM is slow, obsolete, a loan from a friend. When she first gat it. Janet could do little more than flip the on-off switch. She taught herself how to use it to keep track of her investigation, her notes, her burgeoning files, her letters to Ranger Anderson.

Her best friends know him as Don. The Ranger. The “other man” in Janet’s life. She talks to him almost every day-often several times a day. It sometimes seems, even to Janet, that she spends more time communicating with Anderson than with her husband.

Janet and the Ranger first talked on December 15, 1991, the day she learned that her beloved older sister was dead. Sandy, 34, had been missing since Friday, December 13. Janet had spent a restless Saturday night, trying not to think the worst. But early Sunday morning, the worst was confirmed. Sandy’s body had been found in her car on a rural road near Royse City, a small town 20 miles east of Garland. She had been killed by a single shotgun blast to the head. Twenty-eight-year-old Janet had gone with her husband and brother to the Medical Examiners Office to identify Sandy’s body, but she was so upset she couldn’t bring herself to look at the photographs. Janet’s husband, trained as a paramedic, verified Sandy’s identit

That afternoon. Ranger Anderson phoned the Garland home of Shirley and Herbert Harper, Sandy and Janet’s parents. Grieving, shocked, Janet and other family members had gathered there trying to fathom what had happene

Janet took Anderson’s call. In a slow Texas drawl, Anderson asked what was going on in Sandy’s life, if Sandy had business in Royse City. Janet couldn’t think of any possible reason Sandy would be so far from her Garland apartment on Bobtown Road, especially on a Friday nigh

She told him about Sandy’s recent divorce from an abusive husband, how she had lost more than 150 pounds, about her love affair with and engagement to a man named Leon Andrews. From the phone, Janet could see Leon sitting at her mother’s kitchen table, hunkered over, weeping as if he were in physical pai

Janet felt; sorry for Leon, but she was angry at him, too. In a rush, it all tumbled out: how Sandy told her friends and family she was afraid of Leon’s former wife, Loretta. Sandy had said that Loretta repeatedly threatened her, that she had thrown a beer bottle at her door and screamed at her in public for sleeping with her husban

Anderson said little. When Janet asked if Sandy had been raped, he said he wouldn’t know until the autopsy was completed. It appeared that Sandy’s clothes had been removed after her death. Perhaps it was die work of a serial killer or a necrophilia

“A necro-what?” Janet asked. He explained that was someone who had sex with a dead person. She had never heard of anything so disgusting. Janet and Sandy had grown up in a very religious home, As children, they had been sheltered, not allowed to watch TV or go to movies. Now she was hearing that her sister not only had been murdered but could have been attacked by a necrophilia

Then Anderson asked a really odd question: What size foot did Leon have? Someone involved in the murder had left muddy prints; it was a small foot, wearing a shoe with an underslung heel and a pointed to

“Like a lady’s foot?” Janet asked. “Could be,” Anderson replied. That confirmed her suspicions. Janet wanted him to arrest Loretta immediately. Don Anderson simply listened, like a human vacuum cleaner sucking up all available bits of information.

Though neither realized it at the time, it was the start of an unusual relationship: the taciturn investigator with more than 30 years of experience and a woman not yet 30 whose life had run in comfortable circles around her husband, her two children and her small house-cleaning business.

Janet Holley turned sleuth, digging to find out who murdered her sister, Sandy. then feeding that information to Anderson who was 30 miles away in Greenville. But as she dug, her initial feeling that Loretta was the killer began to waver. Could Sandy have been killed by someone else, someone she cared about, someone so deceptive, so manipulative that she never realized her life was in jeopardy?

And as she got closer to the truth. Janet began to wonder: Would she and the Texas Ranger ever be able to prove it?

“I GUESS YOU’RE WHAT A TEXAS

Ranger should look like,” Janet said as she shook Don Anderson’s hand. Anderson had the air of an old-fashioned lawman: weathered face and square jaw beneath a cowboy hat, solidly built body wearing tan Western-cut dress pants, a white Western shirt with a silver star on the chest, a dark tie with a Ranger lie tack and cowboy boots, Though they were indoors, he kept his hat firmly on his head.

It was Thursday, the day after her sister’s funeral. Janet introduced her father, brother and sister-in-law to Anderson. Her husband. James, had returned to his job as a quality control manager for a sprinkler manufacturer. The other family members had driven out to Greenville to Anderson’s cubbyhole office at the Hunt County Criminal Justice Center. As they drove east on Interstate 30 past the Royse City limits, Janet wondered which of the rural roads the killer had driven that night. She still knew little about the crime.

While Anderson told them about the history of the Texas Rangers. Janet looked around the office. Ranger memorabilia filled a small bookcase; a copy of a painting of a Western lawman riding into town-“Enter The Law”-had a prominent place on one wall.

The oldest police organization in the state, the Texas Rangers began as a handful of men organized by Stephen F. Austin in 1823 to protect settlers coming to Texas. In 1935, the Rangers were put under the aegis of me Texas Department of Public Safety. Chosen through a highly competitive testing process, members have an elite reputation; there are currently only 96 Texas Rangers. Though the post is open to anyone with eight years of experience in law enforcement (two years must be with DPS), no woman has yet become a Texas Ranger.

Now 58, Anderson entered the DPS Academy in 1962-a year before Janet was born. He was 27 years old and had worked in construction and aircraft mechanics and had played professional baseball for the old Sherman-Denison Twins.

Anderson worked as a state trooper for years, then decided he wanted to be a Texas Ranger. After applying several times, he was inducted into the Rangers in 1979 and is now assigned to Hunt and Collin counties. Anderson is one of the few Texas Rangers with a master’s degree. He studied sociology, the closest thing to criminal justice offered at East Texas State University.

Texas Rangers usually work on major felony investigations when asked by other law enforcement agencies to assist on specific cases. They often help not only in criminal cases, but also with special inquiries involving public officials. On the morning that Sandy Dial’s body was found, the Hunt County sheriff called and asked Anderson to help with the investigation.

A quiet, self-contained man, Anderson has had many distraught family members sit in his office. “Homicide is always traumatic,” he says. Family members frequently call him to keep up with investigations. They offer advice, ask questions. But no family member has ever gotten as involved as Janet Holley.

A pretty woman with perfect skin and short, frosted hair swept back off her face, Janet looked impeccable that morning, as usual. Her nails were done, her makeup just so. But as she sat in the Ranger’s office for the first time, Janet was in turmoil. She had spent every hour of the last few days speculating about what had happened to Sandy. Sandy hadn’t been just a sibling or a friend; she had been like a second mom to Janet.

Though they were close, the two sisters couldn’t have been more different. Sandy was dark-haired, placid, sweet-natured. For years, she’d battled with her weight, once weighing as much as 300 pounds. Janet, on the other hand, was blond and thin, with a fiery temper. As a teen-ager, she had rebelled against the strictures of their Pentecostal upbringing. Sandy had simply accepted them, anxious to please her parents. Janet remembered all the times Sandy had bailed her out of trouble or smoothed over her contretemps with their parents. Now she was gone forever.

On Monday, Janet had gone to Williams Funeral Home in Garland and picked out Sandy’s coffin-white with pink roses. Sandy’s ex-husband, Lynn Dial, came by but left quickly; his and Sandy’s daughters, Miranda and Breana, were living with him.

Janet helped arrange the services, only to find herself furious because the preacher refused to mention Leon. The rest of the family agreed with him, though; after all, what if they found out Loretta was to blame for Sandy’s death?

Even if Loretta had caused Sandy’s death, Sandy loved Leon and that’s what counted with Janet. “I defended him to the hilt,” Janet says. At the time of her death, Sandy and Leon were living together, planning a Valentine’s Day wedding. Though Leon had waffled between Loretta and Sandy for a year, he had finally gotten a divorce and had asked Sandy to marry him. Janet lost that argument; there would be no mention of Leon at the funeral.

Tuesday afternoon, Janet and her brother Byron’s wife sifted through the sacks of haphazardly kept documents that had been collected at Sandy’s apartment. The family was concerned about funeral expenses and about the future needs of Sandy’s daughters, especially Miranda, the oldest girl, who is hearing impaired.

Her parents knew Sandy had at least two life insurance policies: one at work and one taken out only a month before her death. Through her job at Excel Logistics, she had a policy for $30,000. On Monday, the family learned that Lynn, her ex-husband, was still listed as beneficiary of that policy. Sandy had told her mother that she planned to change that policy on December 16-the Monday after she was killed-to make her parents the beneficiaries. She never got the chance.

In the sacks of papers Janet found documents from Farmer’s Insurance Group. Sandy had purchased a $75,000 life insurance policy from the company on November 19, 1991, naming her children as primary beneficiaries and her parents as contingent beneficiaries. She had renewed her car insurance and the salesman insisted that, as a single parent, Sandy needed life insurance as well. Janet found a canceled check to Far Tier’s for $14.78, a stack of premium quotes and a consent form for a physical. A paramedic had come to Sandy’s apartment only three days before she was killed to do the exam.

But she ah also found a draft for $ 18 made out to Met Life on Sandy’s checking account. A conversation Janet had the night she found out Sandy was dead began to make sense.

A friend of Sandy’s named DeEllen Bel-lah had called Janet that Sunday evening, asking if she 1 lad found anything in Sandy’s belongings about a life insurance policy. She said Sandy had made her the beneficiary of a polit y to ensure that Sandy’s two daughters received a college education should anything happen to her.

DeEllen and Sandy had known each other for seven or eight years after meeting at a paper goods company called James River, where Sandy had worked as a data entry clerk. DeEllen had called Janet before, after she’d left James River and had gotten a license to sell insurance. DeEllen wanted to sell Janet an insurance policy designed to provide funds for future college costs; Janet had declined. Janet had actually met DeEllen only once, at a birthday party for Sandy and Janet’s mother. “She flitted in and flitted out,” says Janet.

For years, Janet had wondered about Sandy’s friendship with DeEllen. Sandy had confided that DeEllen was married, but had a “sugar daddy,” a well-to-do lover who gave her money and diamond jewelry. Sandy thought DeEllen was glamorous, a femme fatale. DeEllen’s intrigues made Sandy’s own rocky marriage seem even worse in comparison, especially after DeEIIen started seeing Lynn’s brother, Donnie Dial, while maintaining her relationship with the sugar daddy.

From the brief meeting at the party, Janet thought DeEIIen appeared to be a successful, upper middle-class woman; she carried herself gracefully and wore expensive clothes and lots of jewelry. Sandy had told her of DeEllen’s fondness for the best of everything; even her children had to have designer clothes. But at 5 feet 4 inches tall, with bleached blond hair and a scattering of acne scars from her teen years, DeEIIen wasn’t drop-dead gorgeous. Janet didn’t understand the appeal she held for men. But she knew Sandy had looked up to her. Still, why would Sandy make DeEIIen the beneficiary of a life insurance policy?

“She didn’t think anyone in her family was capable of making sure that her girls went to college,” DeEllen told Janet. Could that be true? Janet remembered her parents offering to send her and Sandy to college and their disappointment when their daughters got married instead right after high school. And, as a single parent, Sandy had relied so much on her parents; she talked to her mother almost every day on the phone.

Though Janet knew that DeEllen and Sandy had once been close, in recent years they seemed to have drifted apart. DeEllen had divorced her husband. Clay Fuller, and was seeing Donnie Dial. Sandy told friends and family that Donnie seemed to hate her. He refused to let Sandy and DeEllen see each other anymore.

In fact, on the Friday night she had disappeared, Sandy had told her daughters she was going to DeEllen’s house, but not to tell their father, Lynn Dial. She didn’t want it to get back to Donnie Dial. But for some reason, Sandy’s plans apparently changed. DeEllen says that Sandy did not come over that night.

On the phone that Sunday night after Sandy’s body had been found, DeEllen went on, telling Janet that Sandy was “a real ass” when it came to men, that she had probably gone out drinking and been picked up by the wrong guy. DeEllen confided that Donnie Dial, a former police officer, had been out to the scene earlier that day and he thought it looked like some kind of “weird sex crime.”

The conversation was strange. “DeEllen talked about it like she was talking about a story she had heard on the news,” Janet wrote in her journal. She was supposed to be Sandy’s friend. DeEllen didn’t seem sad; she sounded excited.

DeEllen said she thought that Sandy’s life had been insured for $10,000 with “Metropolitan,” but that the policy had been purchased so long ago, she didn’t know if it was still in effect.

The whole thing sounded improbable to Janet. But on Tuesday, as Janet looked at the draft for $ 18 to Met Life, she began to think that perhaps Sandy did name DeEllen the beneficiary of a life insurance policy. She remembered a conversation with Sandy months before her death. After swearing Janet to secrecy, Sandy confided that DeEllen’s sugar daddy had given DeEllen $30,000 in trust for each of her two children’s college funds, and a $30,000 life insurance policy. DeEllen was making Sandy the beneficiary of that policy. “That made Sandy so proud,” says Janet. Maybe Sandy was simply returning the favor.

Wednesday, December 18, the morning of Sandy’s funeral, Don Anderson called Janet. She wasn’t up to talking. They agreed to meet the next day. Before hanging up. the Ranger asked her to watch for anyone behaving strangely at the memorial service, to take notes of anything she saw that seemed odd.

Four hundred people showed up for the service at Peace Tabernacle in Mesquite. Despite her grief, Janet tried to follow Anderson’s instructions. But she didn’t notice anything weird, except for DeEllen. Janet saw her leaning against the wall of the church as everyone else was getting in line to drive to the cemetery. On the phone with Janet that night, DeEllen explained that her daughter had locked the keys in their car at the church; she had been waiting for the locksmith.

Janet thought that was curious, ’if that had been my best friend,” Janet says, “come hell or high water I would have hitched a ride to the cemetery to say goodbye, if I had to ride in the hearse.”

Thursday, Janet and other family members talked to Anderson for three or four hours, telling him all they could recall about Sandy and her life in recent years. Janet told him about DeEllen and the life insurance, but she kept coming back to Loretta, Leon’s ex-wife: her warnings, her threats, her jealousy. Anderson asked questions but provided little information and that infuriated Janet

But she would later remember one strange question. Anderson asked Janet’s father if he had sent Donnie Dial to the scene to look for Sandy’s purse, which was missing. Herbert Harper said no, and Janet saw Anderson exchange glances with a Hunt County deputy standing nearby.

Friday, Janet woke up and got on the phone, calling Leon, Sandy’s ex-husband, Lynn, and other people who knew Sandy. asking them what they knew about Sandy’s final days. But she kept coming back to the $10,000 life insurance policy. Something wasn’t right. Janet had found a check for $14.78 to Farmer’s for a $75,000 policy. Why was there a draft on her account for $ 18 if the Met Life policy was worth only $10,000, so much less?

It didn’t make sense, especially because Sandy had little extra money. ’’Sandy’s budget was so tight,” Janet says. “I would call and invite her over and she couldn’t come because she didn’t have the gas money.” Shortly before her death, their brother, Byron, had rigged up the muffler on Sandy’s black Pontiac 6000. It was rattling badly, but Sandy couldn’t afford to replace it.

Janet called the Mesquite office of Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., asking if there was a policy on Sandy Dial. The clerk asked her the name of the beneficiary. “I think it’s DeEllen Bellah,” Janet told her. The clerk came back. Yes, there was a policy. For $100,000.

Stunned, trying not to become hysterical, Janet hung up the phone and dialed Anderson’s number to tell him what she had found out. After that, it seemed like every time she talked to someone who knew Sandy, she learned that DeEllen had called first, talking about the investigation, the insurance, how Sandy didn’t trust her parents to take care of her kids. Why then had Sandy made her parents the beneficiaries of the $75,000 Farmer’s policy? It didn’t add up.

“’After I discovered that DeEllen had lied to me about the amount of the life insurance,” Janet wrote in her journal, “I felt it best that I not deal with her anymore. The next time she called, she wanted to know ’Now what’s being done about the investigation? How long has it been since you talked to the Ranger?’ During the whole conversation I was evasive and not answering any of her questions. This went on for about 30 minutes and I believe she got the drift, because I never heard from her again after that.”

But Sandy’s friend was not out of her life; Janet wag just beginning to learn about DeEllen Bellah.

WEAR)ING OLD BOOTS, JEANS AND gloves, Janet trudged into the pile of rubbish. TJhough it was only March-a few months after Sandy’s murder-it was already hot. The smell of old bedding, rotted clothes, decaying furniture and sacks of garbage drifted over her. It was one of those rural dumps that had stalled years ago with a few bags of trash in a small ravine and had grown as people who knew the out-of-the-way spot brought their refuse.

Janet had gone to three Dallas-area psychics, searching for information about Sandy’s death. Don Anderson scoffed at her tactic, “We don’t have time to waste following up leads provided by psychics,” he told her. “1 don’t believe in psychics.”

But Janet was unapologetic. Her attitude was “it might help and it can’t hurt.” And she was intrigued when one psychic said Sandy’s misting purse was under a piece of tin, like the roof of a barn, near a trashed commode at a dump, near a cemetery. Sandy’s body had been found in her car on Hunt County Road 2646. Anderson had told her there was indeed a small dump only a few feet away. And hidden behind tall weeds beyond the dump were a few old graves. She corralled her parents, her best friend, Kelli Gravely, and several other relatives and drove out to the site. She found the toilet and a large piece of tin.

But then; was no purse, nothing that might have! been Sandy’s. Another dead end.

In the three months since Sandy’s death, there had been lots of dead ends. In January, Janet had settled into a routine: She cleaned hauses during the day, mulling over a new bit of information as she scrubbed bathtubs and mopped floors. She spent all her spare time on the phone, trying to get information about Sandy’s murder. When she learned something, she rushed to call Don Anderson.

Janet ha|d also discovered more about Loretta Andrews-that she was a short, stocky woman with auburn hair and a fiery temper and that she decorated cakes for a Garland bakery. Only weeks after Sandy’s death, Leon had returned to her.

But Janet was frustrated. Ranger Anderson didn’t seem to be taking Loretta seriously as a suspect.

After interviewing Loretta, Anderson thought it unlikely that she had anything to do with the murder. “She was right up front with me,” says Anderson. Loretta admitted threatening Sandy; Sandy was stealing Loretta’s husband from her. But Loretta had agreed to the divorce and was living with another man, And Loretta had an alibi; she had been at a wedding rehearsal the Friday night that Sandy disappeared. Anderson told Janet there was no evidence that Loretta was involved.

Janet wasn’t completely convinced about Loretta’s innocence, but she began to consider other possibilities. She asked Anderson about Jake (he asked that his last name not be used) and Steve Lynch, two men with whom Sandy had had affairs.

Sandy had befriended Jake, a man several years her junior. It was the late ’80s, and Sandy was miserable in her marriage. Sandy had told Janet that from the day they wed, she knew the marriage to Lynn was a mistake. He constantly belittled her. After she gained a lot of weight during pregnancy, he began calling her a “fat slob” and telling her how ugly and worthless she was. After a dozen years of marriage, Sandy weighed almost 300 pounds.

“She had totally lost her self-esteem,” says Janet. Lynn worked nights as a security guard for the Garland Independent School District; Sandy worked days, They slept in separate bedrooms.

At the time Sandy met Jake, he was living next door with his grandparents. A troubled young man who had had a few run-ins with the law, Jake needed direction.

Janet soon realized that their relationship was more than a friendship. Jake was constantly at Sandy’s house, and Sandy later confided that they had an affair. She started paying attention to her appearance. When Jake was around, Sandy was upbeat and happy. “He respected her opinions,” says Janet. “I don’t think Sandy ever felt her opinion counted.” Lynn never seemed jealous. After being kicked out of his grandparents’ house, Jake briefly moved in with Sandy and Lynn.

With Jake’s encouragement, Sandy started losing weight, winning $50 in a weight-loss contest at work. In a few years, she had lost 140 pounds.

In 1990, Sandy filed for divorce from Lynn. But she didn’t want to marry Jake; he was in trouble with the law again. Jake says they parted on good terms, but one of Sandy’s friends told Janet that she was afraid she might be dragged into his problems.

After the murder, Anderson visited Jake, who was in the Dallas County jail on a burglary charge. But he told Janet that Jake had no motive-and his shoes were size 12. Too big to match die prints at the scene.

Well, Janet asked, what about Steve Lynch? Sandy had met Steve (not his real name), a tall, handsome house painter, at a fish fry at a cousin’s apartment in early November, only six weeks before her death. Leon, who once again was waffling about his relationship with Sandy, had gone back to his wife, and Sandy was dating. The group later went dancing at a club at The Villa Inn East Motel in Mesquite-a place Sandy called “a hole in the wail.” But Sandy told Janet the next day she’d had “the time of her life.” She and Steve had danced and parried until late that night; she took him home and they slept together- the first time in her life she’d ever done something so wild, so irresponsible. Maybe, she confided to Janet, he was The One, Mr. Right.

But later that month, about a year after they had first become lovers, Leon came back into her life with roses and divorce papers. Sandy told Steve that she was getting married. Steve, not interested in a serious relationship, had simply congratulated her. Now Janet wondered if Steve had really taken it that well. Her suspicions were heightened when she found out that Steve’s first wife had been found shot to death in her car in a Collin County park in 1987. The death was ruled a suicide, but the coincidence was eerie.

And what about The Villa, the place they had danced all night? DeEllen had told the family that Sandy had called her the Friday evening she disappeared and wanted to get something to eat. DeEllen declined, saying she had already eaten supper. Sandy told her that she was going to eat. She might come by, but she might go to “The Village.” When DeEllen was later asked if Sandy could have meant “The Villa,” DeEllen said. “Oh, The Villa! That’s what it was.” Had Sandy gone to The Villa for a last fling with Steve Lynch?

But Janet found out that Don Anderson had already paid a visit to Steve Lynch, or more specifically, Steve’s closet. Anderson looked at Lynch’s shoes, size 12. Lynch’s feet were also too big to fit the muddy prints.

Janet’s obsession began taking a toll on her emotions. She was getting paranoid, nervous. She asked her brother to stay with her one day while she cleaned a client’s house. Her father gave her a key ring with a can of Mace attached. One evening while her husband was at paramedic school, she heard a noise on the roof and called the police, convinced the murderer was coming after her. All they found was a cat.

Early in her investigation, about a month after the murder, Janet woke up but couldn’t get out of bed. She was “mentally zapped.” She canceled her cleaning job that day, pulled the covers over her head and slept. That afternoon, she called Anderson, who gave her an assignment: Call Garland Crime Stoppers to see about getting a reward fund set up.

She called Larry Rollins, the man in charge of Crime Stoppers, and learned that they would put up $1,000 for information leading to the grand jury indictment and arrest of Sandy’s killer. “What’s a grand jury?” Janet asked. She spent several hours talking to Rollins, learning how the criminal justice system works.

Four days later, Janet had raised an additional S4.000 to add to the $ 1.000 Crime Stoppers reward and had organized a small army to post fliers showing Sandy’s picture and her car. On a Saturday in late January she called local television stations who sent crews out to tape the 75 friends who showed up to post the reward notices. That evening, Janet’s efforts made Sandy’s murder one of the top stories on the newscasts of channels 4, 5 and 8-it even made the Spanish language station.

When mapping the routes, Janet and a woman friend drove to County Road 2646 where Sandy’s body had been found. “We were scared to death,” she says. But as she drove along the dirt road, she realized that the murderer couldn’t have chosen the place at random, especially in the dark.

For the first time, Janet began to think that Loretta was not responsible for Sandy’s death. She believed it was unlikely that Loretta Andrews could have known about this road.

It also made something she had heard through the grapevine-from a relative of a relative who knew someone at the Royse City Police Department-hit home. Janet could look south from where Sandy’s body was found, and there, across a pasture, was a house that Donnie Dial and his ex-wife, Debbie, had bought when Donnie worked for the Royse City Police Department. Out of all the rural roads between Garland and Royse City, why did Sandy end up near his old house?

The next day one of Janet’s relatives who had gotten the assignment to post (Tiers in DeEllen’s neighborhood in Rowlett called. He had driven through that area again and discovered that every flier had disappeared.

Everything, Janet realized, kept coming back to DeEllen Bellah and Donnie Dial.

DON ANDERSON POINTED OUT A piece of broken white cement embedded in the dirt road. He told Janet that someone had stepped in Sandy’s blood, and then in mud and then onto the cement. He had a photograph of the print, but the rains had washed the print away.

It was a beautiful, clear day in September. Janet was back on Hunt County Road 2646. But this time, Janet wasn’t here to dig through trash. This time, she had come out with Anderson to put together all the bits and pieces, all that she had learned about how her sister had died 10 months before.

In the intervening months, Janet had not backed off; if anything, she had become more obsessed. “Janet is very aggressive,” says her husband. “Once she sets her mind to something, she goes all the way.”

And she has a knack for getting people to help her. “She makes a friend,” says Kelli Gravely, Janet’s neighbor who has helped her at times. “She gets close to people. She can talk to people and get them to talk to her.” Janet has no qualms about walking up to a bank manager or court clerk and telling them her sister has been murdered and she needs their help. Most often, they are sympathetic, telling her what she needs to know, giving her documents it might take Anderson a subpoena to get.

And she is resourceful. Anderson asked if she had a sample of DeEllen’s handwriting. Janet said no, but she was asleep one night when it hit her: In the pile of papers they had scooped up at Sandy’s apartment, Janet had found a card DeEllen had sent Sandy in the summer of 1991. It read “To My Sister,” and Janet remembered how proud Sandy had been that DeEllen thought of her as a sister.

The Ranger was impressed. “I’m going to have to put you on study with me,” Anderson told her.

When Janet got a copy of the autopsy report, she learned that Sandy had the equivalent of a few drinks in her system when she died. She knew Sandy would never have gone to a bar alone; she had to be at a restaurant with someone she knew or at a friend’s house if she was drinking alcohol. But Garland and Mesquite are dry areas. Where could she have gotten a drink?

Janet remembered visiting TGI Friday’s in Piano with Sandy the previous October. Janet had purchased a Unicard-a membership that allows the holder to buy alcoholic drinks in dry areas at participating restaurants-so that the sisters could have margaritas. What if Sandy had bought one?

A clerk for Unicard verified that Sandy indeed had signed up for the membership not long before her death. The last time she used it: December 18. When Janet heard the date, her heart started pounding. That was the date Sandy had been buried. But that wasn’t all. The records showed the card had been used that night at The Villa.

Feeling sick in the pit of her stomach, she called Anderson. Crying, Janet explained what she had found. “The murderer used Sandy’s card!” she sobbed.

The Ranger visited The Villa, but found that the small Unicard computer was unplugged and sitting beneath the counter. The service was seldom used. Only four cards had been run through that month; Sandy’s card had been run through twice within a few minutes, But the bartender on duty on the 18th didn’t remember running Sandy’s Unicard.

DeEllen was the one who had talked about Sandy going to The Villa before her death. Yet, for every answer. Janet had more questions. She finally asked Anderson to go with her to the scene where Sandy’s body had been found. She wanted him to explain what his investigation had revealed about Sandy’s murder.

From his interviews and examination of the physical evidence, Anderson believed that Sandy had been killed on December 13, a Friday night, and that at least two people were involved in her murder.

It was her ex-husband’s weekend to have their daughters; Lynn came to pick them up at 6 p.m. Before he arrived, Sandy told the girls she would be at DeEllen’s house that night. DeEllen lived on Horizon Street, a few miles away in Rowlett.

Leon, on his 6 p.m. break at work, called as the girls were leaving. Sandy told him, too, she was going to DeEllen’s house. She said DeEllen and Donnie had been quarreling and her friend wanted to talk. Sandy gave him DeEllen’s phone number so he could call her on his 9 p.m. break.

But at about 6:30. Sandy phoned a friend named Kathy Myers, who lived next door, asking if she wanted to go shopping. Kathy couldn’t go, but she told Sandy thai if she couldn’t find anyone else to go with, to call her back. Ten minutes later, Sandy was on the phone again. In a rush, she told Kathy she’d found someone and not to worry, Kathy went to the door of her apartment to call her daughters in for supper and saw Sandy hurrying to her car. No one reported seeing Sandy alive after that.

On his 9 p.m. break, Leon called the number Sandy had given him for DeEllen. A woman answered, but didn’t identify herself; Leon didn’t know DeEllen and didn’t recognize the voice. Leon asked for Sandy, and the woman said she wasn’t there.

Sometime that night between 9 and 9:30, Robert Logston, who lived on Forehand Lane just north of 1-30 near Royse City, stepped to his bay window to turn on the Christmas lights ringing the pond in front of his house. He saw two cars driving toward his house; the second car had its lights off. One car was making a noise like it had a loose muffler-like the muffler Sandy’s brother had rigged on her car.

Logston kept watching as the cars drove past the junction of Forehand Lane and County Road 2646, passed his house and parked briefly. Minutes later, the cars turned around and drove back past his house.

Between 9:30 and 10, a farmer was standing in his front yard facing 2646. He saw two cars-this time both had their lights on-turn onto 2646. The farm road runs in front of his house, past the house formerly owned by Donnie Dial, then curves through pasture back to Forehand Lane. The cars drove down to a bend in the road, where the road turns from stone to dirt, switched their lights off and parked. He thought it was teen-agers making out or someone using the illegal dump.

On Sunday morning at 8 a.m., an 81-year-old farmer named L. E. “Pud” Campbell was driving down 2646 to check on his cattle. He saw a black car parked by the side of die road. He looked in the windows and saw a nude body lying across the back seat. Badly shaken, he drove to Logston’s house and they called the police.

Notified by the Hunt County Sheriff’s Department], Anderson arrived about 9:20 a.m. One of the first things he noticed was the footprints. It had rained on Thursday night and the dirt road was muddy. Whoever drove Study’s car to the scene had gotten out of die driver’s seat, then walked to tie left back dd>or and opened it; there was a muddy print where the driver had stepped in Sandy’s blood. which had spilled to the ground. The driver had small feet, about 8 1/2 to 9 inches long, and was wearing a shoe or boot with a pointed toe and an underslung heel. It would have taken a man with a size # or 5 shoe to make me print.

Sandy’s head hung down on the back floorboard.! She had been shot with a shotgun in the right side of her skull; the blood and brain matter on the floorboard were an inch deep.

At first glance, it looked to Anderson like a kidr|ap and rape. Sandy was nude. Her pink sweatshirt had been pulled over her head and was dangling off her left ami. Her black leggings, panties and pantyhose were in a pile on the front seat.

That day, Anderson explained to Janet that the pruts indicated that the driver had walked around behind Sandy’s car, opened the other back door and stepped up into the car to remove Sandy’s clothes after her death; her) body was smeared with blood and maneuvered onto her stomach in a sexual position, initially giving Anderson the idea that the killer might have been a necro-philiac. Her tampon had been removed and was on the) right back floorboard.

An autopsy would later show no sign of sexual assault. And there was no sign of a struggle; Sandy’s nails were unbroken and her only injury was the fatal wound to her head. Anderson says she might have been killed there, or shot elsewhere and driven to the scene.

Though) Sandy’s purse was missing, she still wore her gold necklace, and in the trunk of the car were two commemorative guns and silver pieces owned by Leon, who was still moving into Sandy’s apartment

After removing her clothes, the driver shut the back door and walked behind Sandy’s car again. He or she then stepped to the passenger side of another car parked in front of Sandy’s sedan and got in. Then the second driver drove away. From the tracks in the mud, Anderson believes the second car had four-wheel or front-wheel drive; the second car spun out like it was leaving in a hurry.

As Anderson walked her through the scene, Janet began to visualize what happened to her sister. She saw a photo of the footprints walking up to the side of the second vehicle and disappearing. She was angrier than she had ever been in her life. “They were going on with their lives and left Sandy lying there dead,” she says.

While they stood on the dirt road. Janet asked where Donnie Dial had been standing that Sunday when Anderson was first called to the scene. “What are you talking about?” Anderson asked. He had not seen Donnie until Monday afternoon. Donnie had appeared at the scene and said he had talked to Sandy’s father, learned the purse was missing and had come to look for it.

Janet went back to her journal. On Sunday night, DeEllen had told her that Donnie Dial had been to the scene and it looked like “a weird sex crime,”

But if Donnie had not been at the scene until Monday, Janet wondered, why did DeEllen say that?

JANET SPREAD THE 75 CANCELED checks out on the table. She had gotten them from Sandy’s bank and the signatures were incredibly consistent. Sandy always signed her name the same way. No loops, no nourishes. Janet compared them to the documents before her: an application for a Metropolitan Life insurance policy for $100,000 and a change of beneficiary form, The signatures of “Sandy Dial” on the doc-uments didn’t match the checks. They weren’t even close.

Only days after Janet visited the scene with Anderson, the Ranger had called to tell her that Metropolitan Life had filed suit against DeEllen Bellah and Sandy’s two children, alleging that the insurance policy had been fraudulently obtained and that DeEllen was a suspect in Sandy’s murder. DeEllen had filed a claim on the policy; so had Lynn Dial, as the father of Miranda and Breana, co-beneficiaries. Metropolitan was contending that the signatures on the documents “may have been forged” and that Sandy Dial may have had nothing to do with obtaining the policy.

Now Janet and her father were sitting in the office of an attorney representing Metropolitan; Janet had called the attorney. explaining she had some information the attorney might be interested in.

She remembered DeEllen saying that the policy had been taken out “so long ago, I don’t, know if it is still in effect.” But the policy actually had been obtained on July 26, 1991, only six months before Sandy’s death. For Sandy’s home address, it listed DeEllen’s address on Horizon. The home phone number was DeEllen’s. And Janet noticed that the work number listed for Sandy was one digit off Donnie Dial’s home number. Apparently no one from the insurance company had ever met the “Sandy Dial” who took out the policy. A memo in the file indicated that the purchaser wished to handle the transaction by phone and mail only.

Janet learned that the initial application for the policy had been rejected because the beneficiary-DeEllen Bellah-had “no insurable interest.” She wasn’t a relative or a business partner. But the agent had advised “Sandy” to simply refile the application naming her children beneficiaries. Later, she could change the beneficiary back to DeEllen.

That’s what happened. The application had been resubmitted and accepted; only days later, the form changing the beneficiary from Sandy’s children to DeEllen had been sent in.

Then there was the matter of the fingerprints. When Don Anderson sent the insurance documents to be tested, none of Sandy’s fingerprints were found. But DeEllen’s prints were on the application, the change of beneficiary form, an $18 check written by Sandy for the first premium and on a consent form for the physical examination performed by a paramedic who came to DeEllen’s house on June 13, 1991. Who had die paramedic actually examined?

Janet and her father talked about the documents as they left the office that afternoon. It wasn’t until she dropped him off that she began crying so hard she could hardly drive home to Sachse.

She knew Anderson had been focusing more on DeEllen and Donnie in recent months. He had interviewed them extensively. DeEllen’s alibi was that she had been home that night with her two children. But when Anderson spoke to the children, neither of them could remember that night. Donnie claimed he was home alone at his own apartment.

Though Donnie and DeEllen asserted they knew nothing about Sandy’s death, both had failed lie detector lests. Janet had heard that Sandy’s signatures might be forged, that die fingerprint analysis indicated that Sandy had never touched the paperwork. But this was the first day she had seen everything laid out. Why would someone forge life insurance documents? And who-really-was DeEllen Bellah?

THE CALENDAR IS COVERED WITH small, crabbed writing; in the fall of 1992, Janet got so busy she didn”t have lime to write on the computer every night. She started taking notes on the wall calendar hanging in her kitchen.

She threw herself into finding out everything she could about DeEllen Bellah and Donnie Dial. Dial was easier: Janet had grown up baby-sitting his children. She knew he had married Debbie Dial when they were both 16. Debbie’s parents and sister had been killed in a car accident. For years, Debbie and Donnie had lived on the proceeds of an estate worth at least S250,000 from life insurance and a court settlement Debbie had received after their deaths.

Though he had been born with no thumbs, Donnie had become a police officer and had a reputation as an excellent marksman. But after working for three years at the Royse City Police Department and two years at the Rockwall County Sheriff’s Department, his law enforcement career ended. Donnie was fired after stopping an intoxicated pedestrian. Though he had been told there was no need for assistance, he chose to leave the man by the side of the road to go to the scene of a light. The man was killed when he walked into traffic.

Donnie married Lori Suzanne Fox, but thai brief marriage ended when he met DeEllen Bellah. Janet began searching documents at courthouses, police reports and deed records to find out more about DeEllen. “Thai’s when I discovered all this public information out there in bankruptcy records, divorce papers,” says Janet

What she learned was anything but reassuring. DeEllen Bellah seemed to have a pattern of using men-and women-to build a glamorous image, one far from her humble beginnings,

Though DeEllen told her friends she was born in 1954, she actually was born in 1958, one of five children of an alcoholic welder and his wife in Bridgeport, north of Fort Worth. DeEllen apparently told people she was four years older to hide the fact that she was only 14 when she married Robert Gober, a member of a rock band. That year, DeEllen also gave birth to her daughter, Michelle: a son named Michael was born four years later.

During an interview with the Ranger, DeEllen told Anderson that Sandy named her beneficiary of the life insurance policy because Sandy knew DeEllen was “educational-minded.” Her daughter, Michelle, attends Baylor University. But DeEllen never graduated from high school It wasn’t until June 29, 1990, when she was 32, that she earned a high-school equivalency degree.

DeEllen was still in her teens when she was detained one night inside a Decatur car dealership; she had bought a new car at the place a few weeks before bill was unhappy with it. She told police that she had picked up a hitchhiker and he had forced her to break into the dealership.

“She stuck with that story,” says one source, who has known her for years, though there was no evidence of a hitchhiker. “Once she gets it in her head what the story is, she never changes it.” No charges were ever filed. DeEllen divorced Gober in August 1984; a month later, she married James Clay Fuller, who owned a dry-wall business in Rowlett.

By talking to people who had worked with Sandy and DeEllen, Janet learned that DeEllen did have a married lover: a well-to-do Dallas businessman, Gerald. (He asked that his real name not be used.) Gerald says he did not give DeEllen jewelry, trust funds or a life insurance policy. “She’s a very convincing liar,” Gerald says.

Her former lover says that DeEllen got a thrill out of living on the edge. “She seemed to take risks that the ordinary person wouldn’t take,” Gerald says. “I think she lived in a kind of fantasy world, She would take any kind of chance to get what she wanted.” He broke off the affair because he believed DeEllen arranged for his wife to discover them, hoping it would force them to divorce.

After leaving the company where she met Sandy, DeEllen got a license to sell insurance policies that could be used by parents to help pay for their children’s education. She worked several days a week in Shreveport and told Gerald she was making $100,000 a year.

But in 1989, she and Fuller filed for bankruptcy. Papers filed in court say she was making S 1,400 per month as regional manager for Southern Security Life, based in Florida. They separated after DeEllen began seeing Donnie Dial, and in 1990, Fuller filed for divorce. Fuller had adopted DeEllen’s children and was awarded custody of them. Though Fuller declined to comment, another source says that DeEl-len’s children were angry at her behavior and did not like Donnie Dial. DeEllen told friends she”d gotten a job as a postal carrier.

It was clear to Janet from court records that DeEllen was in desperate need of money. In addition to the bankruptcy, there was a federal lien for $10,504.37 against the Fullers by the 1RS. Janet also discovered that DeEllen was behind almost a year in her mortgage payments. (The lender later foreclosed on the house.)

But one of the most curious things she discovered was that in October 1990. Don-nie Dial had sued De-Ellen for damages. Though they had been dating for months and DeEllen had told Donnie’s ex-wife, Lori Suzanne Fox, in August 1990 that they were planning on getting married, court documents make it appear that they are mere acquaintances, that she paid Don-nie-who has a history of back problems- $20 to climb on her roof to fix a TV antenna. He claimed that he had fallen and was injured and that DeEllen failed to warn him of unsafe conditions. DeEllen wrote her insurance company, demanding that they settle with Donnie for the limits of her policy-S315,000. The company finally paid $29,000.

One thing that kept bothering Janet was how Sandy appeared to have paid for a life insurance policy she knew nothing about. Janet went through Sandy’s bank records again and found two deposits for SI 8, the amount of the Met Life premium. She went to Sandy’s bank and asked for the microfilm of the transactions. One, on July 22. 1991, was the deposit of a refund check Metropolitan sent after rejecting the first application from “Sandy.” The second was a check from DeEllen dated Sept. 18, 1991,

Janet remembered talking to JoAnn Moreau, a cousin who was close to Sandy, “DeEllen told Sandy she had some bills to pay that Donnie Dial did not know about,” JoAnn said. “So DeEllen would give Sandy the money and Sandy would pay the bill, Once Sandy was concerned her car payment wouldn’t clear because DeEllen hadn’t paid her back.”

With everything she was discovering, Janet started to wonder if she hadn’t missed her calling. She and a girlfriend who sometimes helped her began calling each other “Sherlock” and “Watson.”

But her family was asking, Why you? The Texas Ranger was supposed to be investigating the crime. Why was she working on the case night and day?

The cost has been high: Janet has resigned from the Junior League and her committees at the PTA. Her children haven’t been neglected, but she hasn’t been able to do all the things she used to do for diem.

“Physically, I’m going through the motions,” Janet says. “I’m bathing them and feeding them. But everything’s in a tizzy. I’m not thinking about what to cook for dinner, I’m thinking about DeEllen and all the stuff I’ve dug up about her past.”

Through it all, she kept pursuing Sandy’s killers. Why?

“I’ve said that, too,” says her husband, James. “I’m ready for this thing to be over with.” When the phone rings, their 2-year-old son doesn’t want her to pick it up; the toddler believes that his mother’s ear is per-manently attached to the phone, James says.

“I’ll come home at 4:30, and she’ll be on the phone talking to somebody about the case. At 1l p.m., she’ll still be on the phone. She’ll come to bed and want to talk about the case.”

But he knows why she does it. “It may help her deal with the pain knowing she’s helping bring Sandy’s killers to justice,” James says, [He makes copies of documents and faxes information for Janet, trying to provide support. But he worries about her. While her fear and paranoia have decreased somewhat, she still worries about going to the grocery [store at night. They installed a security system in the house and now keep a loaded .357 in their bedroom. Janet has even taken shooting lessons.

Janet admits she often gets frustrated. After the recent murder of a store clerk, she was furious to learn that 14 detectives had been assigned to the case. Sandy’s murder gets one Texas Ranger.

Don Anderson says that Janet has never criticized has handling of the case, but he knows she|gels disappointed with how slow the process is. “I need to stay on this full time, but I can’t,” Anderson says. He has other investigations, other duties.

Anderson agrees that Janet has been a great help. She has typed statements, given him records of documents, followed hunches that proved accurate. “She’s smart and she’s inquisitive,” Anderson says.

They sometimes joke that Janet is “Junior Ranger Holley.” She’s thought about becoming a police investigator. Anderson teases her, saying that first she would have to become a police officer, serve time on the street, then work her way up to detective. “That doesn’t float my boat,” Janet says. “When this is all over, I’ll have to sit down and think, “What do I want to do With the rest of my life?’ ”

She’s looking forward to the day when someone lis indicted and arrested for Sandy’s murder. She knows that Anderson knows things he’s not telling her. He has not yet released the funds for the $30,000 life insurance policy benefiting Sandy’s ex-husband, Lynn. “We have not eliminated anybody a$ suspects,” says Anderson.

The Ranger firmly believes that Sandy Dial didn’t know there was a $100,000 insurance policy on her life. “1 think she thought that was for DeEllen,” Anderson says. “DeEllen somehow got Sandy to make the payments.” He adds that DeEllen wears a size 7 1/2 shoe, which would fit the prints left at the scene.

The Metropolitan Life lawsuit against DeEllen i| scheduled to go to trial in July. In court documents, she denies forging any documents and is asking that the company settle the claim. She declined to comment through her attorney Craig Barlow. But in September, DeEllen told The Dallas Morning News the lawsuit’s allegations were not true. “It’s pretty scary,” she said. “I don’t know why they would say that unless they’re thinking they don’t have to pay the money.. .On one hand, I feel I have an obligation to her [Sandy |. but on die other hand. I don’t care if they ever pay it.” DeEllen is now living in Wylie, but Donnie Dial has moved away. Neither they nor Lynn Dial, who has remarried, returned phone calls for this story.

Janet believes she knows why her sister was killed. But much of the evidence is circumstantial. Will the Texas Ranger be able to prove it? Anderson thinks so. “There’s no statute of limitations on murder,” he says.

And Janet is not giving up. One Saturday last March, she returned to the neighborhood where DeEllen Bellah was living at the time of Sandy’s death. The house had been vacant for months. Anderson had searched the house but found nothing.

Janet had pestered Anderson for months to canvass the neighborhood; it seemed the Ranger never had time. She finally decided to do it herself, passing out more fliers, knocking on doors.

A woman who lived next door to DeEllen recognized the dark-haired woman in the picture on the flyer. She had seen her park the black Pontiac with a luggage rack at the house next door several times. But the neighbor told Janet she was confused; 18 months before the murder, the woman with short blond hair had introduced herself as Sandy Dial. Stunned, Janet realized that meant DeEllen may have been passing herself off as Sandy for months. Why?

The neighbor also remembered something else odd. In a sworn statement, she said that one evening, at about the lime of Sandy’s murder, she had seen the black car with the luggage rack parked in front of the house next door. Two people were looking in the trunk; a third was holding a large, fluffy comforter-not folded up, but like it was a large baby. His knees were bent, as if the bundle was heavy.

“[ remember thinking they would never get that in the trunk; it was too big,” the neighbor says. She didn’t see anymore. She went inside and shut the door.

Janet wonders, Did Sandy really make it to DeEllen’s house that night after all? Was she wrapped in the comforter? Did somebody else see something? The $5,000 reward is still in force.

But in the meantime, there’s always somebody else to talk to, another lead to follow up.