The fat guy with the Robert Tilton hairdo at Alamo Rent A Car-he’s the first person I think of after my initial meeting with Jose Canseco.

Wait, I can’t call it a meeting; it was barely an encounter. I turn the corner in the Texas Rangers’ spring training clubhouse and there is his billboard-sized back, bearing number 33, taking up a third of the locker room. The back that I’ve been chasing for three months; the back I offered to meet for an interview any time, any place. The back that said no, go away.

Jose? I ask timidly.

He hears but doesn’t turn around. Not good.

Um, here for an interview, whenever you have time, 30 minutes at least-

“Thirty minutes?!” He speaks. “You can get my whole life story in 30 minutes.”

Well, we’ll talk about whatever you want.

He smiles slowly. “Whatever I want, huh? OK, nothing personal. And I can give you 10 minutes after practice.” Oh, great. We’ll talk politics. By now he’s bartering with the photographer. “Fifteen minutes!” Canseco says shaking his head. “If you’re any good, you can shoot it in five minutes.” They settle on seven.

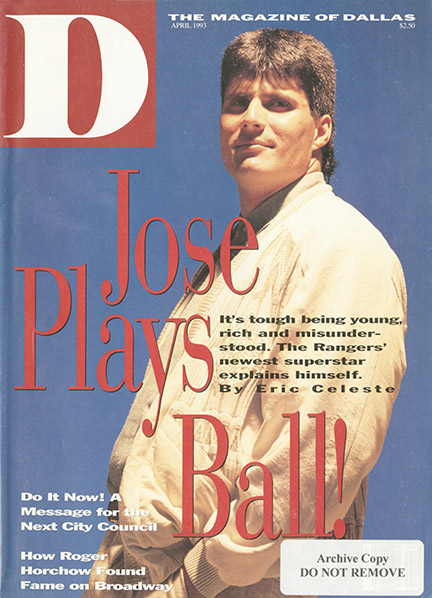

Canseco saunters outside, running his hands through his midnight hair, sans ball-cap as always. He’s headed out to work on popping a baseball into a mitt and out of a stadium. I’m left to think about my conversation trie night before with the guy from Alamo.

“Why you doin’ a story on that bum Canseco?” the fat guy asks. I hesitate, trying to place his remarkably familiar Second City accent. He punches up my car rental reservation on his computer screen, requests a major credit card, then stares at me, waiting or my answer.

Well–

The fat guy shrugs; he’s not listening. “I’m a While Sox fan, so I’m biased,” he says. “I’m from Chicago.” Something in his voice m ikes his name tag a point of interest: Tot x Wendt.

Say, you’re not related to…

“Yeah, George Wendt. Norm, on ’Cheers, ’ Ht ’s my brother. “

I knew it. I knew I should have listened to him. He vas celebrity kin, after all. And given that it now appeared I’d flown 1,003 miles for a 10-minute conversation, I had to ask myself the same question. What was I doing here, in southwest Florida, trying futilely to tame baseball’s brash deity in cleats-that bum Canseco?

TRUTH IS, THE QUESTION wasn’t only rhetorical, it was irrelevant, because I never found him-the bum, I mean. The Jose Canseco most people link they know. The one who was traded by the Oakland A’s to the Texas Rangers last season because he and his evil aura had become too destruc-tive. Te guy who drives too fast and punches people in bars and runs into cars and totes firearms and shacks up with Madonna and leaves games early and kisses mirrors and, and, and. The one described by a longtime Bay-Area baseball writer as “a big, good-natured f-up.”

Oh, sure, after our two-minute conversation I was ready to jump on the he’s-an-overpaid-jerk bandwagon. But the more I watched him with the other players, watched how easily he made them laugh, watched young outfielders come to him on bended knee for advice, the easier it was to understand his wariness. All media, including me, wants a piece of him. Reporters from every paper and magazine and TV station in the country try to cozy up to him, be his little buddy, get the quotes they want, then run away with their interview booty. Canseco, meanwhile, is left behind to take extra batting practice.

Not today, though. Hard rain cuts practice short. Canseco’s sitting in the clubhouse, waiting out the weather, bored.

“Hey,” he says.

That’s me.

“Let’s do this now. I’ve got five or 10 minutes.”

Once the interview rules are straight- write down what he says carefully, because journalists have a history of manipulating words in nefarious ways-it is easy to see the gregarious, smart, mischievous megastar who players and coaches and management and beat writers have promised is the Real Jose. (“If you wait him out,” says Kit Stier, who covered the A’s the past 13 years, “you’ll get something good. He’s just a joy.”) He talks for more than an hour. Suddenly, the bum is gone.

“I’m bombarded with interview requests,” Canseco says almost apologetically. “And what can I do? I can’t shut everyone out, and I can’t give one to everybody. Then I say OK, and people come in with preconceived notions of who you are, then write a negative article.” He shakes his head. “It makes me gun-shy.”

Gun-shy? A 6-foot-4, carefully sculpted, 240-pound pro athlete can’t handle weasel-ly writers? “Maybe my mistake is that I’m a quiet person, and I don’t do enough promoting of what I do. So it’s hard for people to know who I am, I can go to a hospital, spend four hours with a kid, and-nothing. But I get a speeding ticket, and it’s printed all over the nation.

“So people think I’m a crazy, gun-slinging, race-car driving guy. People who know me know how conservative I am.” They know that Canseco’s housemates- now that his divorce is pending-are his 11 giant tortoises, two schnauzers (Bonnie and Clyde), and Zoi, the cockatoo. And they know that if he needs to unwind, the king of speed and sin goes bowling.

Why then, this image problem? Why is it every time he says he’s proved that people are wrong about him, he has to go out and prove himself again? Why do so few have complete faith in him? It goes beyond poor spin control, beyond media feeding frenzies. It’s because first impressions are hard to erase. People remember the abrasive Jose Canseco- the famous guy who broke into the league at 21, too rich and famous for his own good. The one forever remembered in media reports and pop culture as the bad boy of baseball.

But as that noted cultural observer, Miami Herald humorist Dave Barry, said when discussing Canseco’s early career:”When I was 24 I was an asshole. If I’d had a million dollars, I’d have been at least 93 times more of an asshole.”

In other words, perhaps-just perhaps-Canseco has matured. Perhaps for the first time the “new Jose” whom Canseco has spoken of will be seen. He must prove that, at heart, he’s a good guy. And that most dear to his heart is not Jose Canseco, but baseball.

“He may be a ballplayer as well as a legend.” Roger Angell, Season Ticket, after witnessing Jose Canseco’s 1987 spring training.

tWELVE- YEAR-OLD BILLY Bloom waits outside the clubhouse’s west entrance, pressing his face against the chain-link fence that separates him from Jose Canseco’s sleek white Mercedes. Jose will have to come out that door and face the 100 or so autograph seekers sometime, and Billy-his biggest fan, no kidding, with a life-sized poster in his room to prove it-wants his autograph. It’s the main reason he and his brother and mom made the 10-hour drive from Atlanta three days ago. Billy has 72 hours of anticipation bottled up beneath his T-shirt sporting the name “Canseco” and the number “33.”

“He hasn’t signed anything,” says his plenty irritated grandmother, who came from New Jersey to see Billy see Jose. “He just ignores all of us.”

Canseco hasn’t signed autographs since he arrived, and the natives are restless. Yesterday, to avoid signing, he and Julio Franco and some other players told fans they had a meeting they had to get to. The fans were patient then, but they’re starting to get annoyed. Surely he can’t be that busy, they say.

Linda Bloom, Billy’s mother, is still hopeful. “The papers can’t be true about him,” she says. “Surely he’ll sign, if Billy could just get close to him…” The afternoon drags on.

Their vigil already seems to have taken longer than it took the 28-year-old Canseco to make the trek from Cuba to the big leagues. Jose, his twin brother, sister, father and mother-who died unexpectedly in 1984-moved to Florida from Cuba in 1965. His father, a former college professor, stressed his family’s academic tradition over sports. (Canseco’s grandfather was a Cuban supreme court justice.) Nevertheless, Jose played well enough at Coral Park High School in Miami to be drafted by the Oakland A’s after his senior year. He burst into the major leagues in 1986 with Oakland, after being named the minor-league player of the year by Baseball America the year before. That first full season he hit 33 home runs and was second in the American League in runs batted in-117.

In 1987, The New Yorker” s Roger Angel I saw some of Canseco’s power firsthand (“his arms…resemble pipeline sections”) and heard stories from a grizzled veteran coach who claimed Canseco hit the longest home run he had ever seen; then, the next at-bat, he hit one just a bit farther. “People just don’t hit balls that far,” he noted. That season Canseco’s numbers were again impressive and, after moving from left field to his more comfortable spot in right field, Canseco cut his errors from 14 to a respectable seven.

It was his historic ’88 performance, however, that sealed his entrance into baseball Valhalla. He raised his batting average 50 points from the year before, to .307. He led the league with 124 runs batted in. And he put together a display of power and speed that no other baseball player has accomplished: His 40 stolen bases and league-leading 42 homers marked the only time a player has gar-nered 40-plus in each category during a season. He became known as baseball’s first and only “40/40 man.” He was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player.

He has yet to recreate the all-around splendor of ’88, but he has-when not injured-maintained statistical excellence (most notably in 1991, when he hit a league-best 44 home runs and slapped 122 RBIs). Even though injured last season with a nagging shoulder soreness that caused him to cut back his weight training and drop 1$ pounds, his exploits on the diamond can still be stunning. Like the home run he cranked at Arlington Stadium after the trade, when he didn’t hit the ball square, “got under” it, popped it almost straight up into the air-then watched it hang in the sky, forever it seemed, before it landed several rows back in the outfield bleachers. A man not easily impressed, Nolan Ryan, said, “That’s the kind of shot you tell your grandchildren about.”

The kind of shot that makes old-time sages like Angell use the word “legend.”

Canseco, to his credit, doesn’t embrace the legend label. “I’m not yet a legend,” Canseco says, nibbling on a grilled-chicken fillet in the clubhouse. “That comes with yean of consistency. I consider myself a worker, a student of baseball. I study the art of hitting and running. Because everyone has ability; the difference is how much you enhance it.”

He warms to this talk of preparation. That’s surprising, since the rap on him is that he doesn’t work hard at the little things. “There are three things you look at when you’re studying technique-hip speed, hand speed and your legs, your momentum. I work on that, and therefore when a hope run happens, it comes very easily. When everything is technically sound, and all the forces meet at the ball…”-he takes a bite of chicken-“it’s devastating.”

First-year Rangers manager Kevin Kennedy remembers the first time he heard of the devastation. “It was ’ 86, and I was a roving instructor, sitting in the stands in San Antonio. Mel Didier, the great advance scout for the Dodgers, walked up to me and said. ’Kevin, I’ve seen the next superstar. The next Hank Aaron. When he takes batting practice other players come out to watch him.’ ” Kennedy pauses and considers having that type of known commodity on the team. “It should be a lot of fun.”

Should be. If. If he’s healthy again. If he hasn’t-as some baseball people say- already played his best baseball. As I type this, an ESPN analyst is decrying the lack of sports superstars in baseball. “Canseco, at least, was a major force that kept people’s minds on the sport.” He’s already being talked about in the past tense.

“When he is at his best,” says San Francisco Examiner columnist Ray Ratto, “he’s better than anyone else because he can do more things, and do them in a big way. [But] a lot of people. . .think his shoulder problems are going to be chronic. “Jose wasn’t traded just because he’s a pain in the ass,” Ratto continues. “They [Oakland! still have Rickey Henderson, and he’s a pain in the ass. . .1 think they thought his attention was wandering more than usual. It wasn’t all of a sudden they got morality. They thought baseball wasn’t as important to him [Canseco] as it used to be.”

For his part, Jose says he’s fine, physically and mentally. “I’m healthier than I’ve been in a long time. I want to be a 40/40 man again.”

The Rangers would like nothing better. His popularity is founded on his baseball production; the numbers, the Rotisserie league stats, the box scores. But more important to the Rangers’ financial bottom line-and some say to Rangers ownership-is how the persona of Canseco draws fans to the stadium and the ticket booths.

’IF YOU NAME TWO PEOPLE IN BASE-ball who will put butts in the seats, they are Nolan Ryan and Jose Canseco,” says Dallas Morning News columnist Randy Galloway. “If you’re going to get a beer, you get your beer. But when Jose Canseco is up, nobody moves from their seats.”

His nationwide popularity reached its peak in the late ’80s-for example, he had his own number: 1-900-ASK-JOSE-but he’s still considered one of pro sport’s biggest names. Canseco is to baseball what Jordan is to basketball, Gretzky to hockey and Montana to football: a talented athlete who has entered the rarefied air of super-stardom, where an athlete’s name ID is more important than his batting average or minutes played. Somehow he has done this without amending his attitude. He does not smile, shuffle his feet and thank God, Country and Our Sponsors for the wonderful opportunity to play this game. On the contrary, he has spoken openly about the game’s most agitating issue, racism. He’s seen as the game’s most bankable star despite antics similar to those that have kept other supremely talented malcontents from attaining this level of recognition, kept them from becoming beloved. Other home run hitters with better numbers in bigger media markets who inspire yawns from fans must ask themselves, “How does he do it?”

The word is charisma: His combination of looks, talent and machismo makes for a riveting mix. Time and again baseball observers say he simply creates more excitement with a swing and a miss than most players (say, the Rangers’ Dean Palmer) do with home runs.

Canseco is well aware of the electricity he brings to the game. ’There’s the anticipation of greatness when I’m at bat,” he says. “People say, ’What if he would’ve hit that ball?’ When I’m out there, something freaky, something different can always happen.

“That’s why I’m an entertainer. I take the game very seriously, but I enjoy entertaining the fans. People come out to be entertained. That’s how they get their money’s worth.” And he wants to give them that good experience because he seems to feed off the fan’s adoration-in fact, Texas fans’ unconditional acceptance of him is one reason he says he’s so excited about playing here. “People here would cheer me on even if I struck out. They know how hard the game is, and they appreciate the effort. It got to where it wasn’t that way in Oakland. They expected perfection.”

This opinion led to a widely publicized quote-including in D Magazine s Best & Worst issue-that Canseco says was misunderstood. “It’s more relaxed here,” went the statement. “It’s an atmosphere I can relate to. In Oakland it was always win, win, win.”

Canseco says this was a classic quote-out-of-context problem. “AH I was saying was that we had such a winning tradition in Oakland for so many years, that the fans didn’t appreciate the winning anymore. They came to expect winning, and thought it should come easily.”

Canseco knows that little misunderstandings are going to shape his image, because he’s seen so many larger transgressions splashed across a newspaper page. He has, at one time or another: challenged a heckler in the stands to a fight in the on-deck circle; rammed his estranged wife’s car with his auto; been arrested for carrying a firearm in his car; been clocked at 125 miles per hour; arid allowed himself to be photographed leaving Madonna’s Manhattan apartment (the reason one fan at spring training was carrying a ballcap from Madonna’s Blonde Ambition Tour for Canseco to sign).

That reputation for, ah, post-game entertainment-while a source of fan interest-has caused the Rangers little concern “Jose is a good person,” says Genera Manager Tom Grieve, who made the trade that sent Reuben Sierra (Rangers all-time home run leader), Jeff Russell (Rangers all-time save leader) and the talented but star-crossed Bobby Witt to Oakland for Canseco. “He’s done some. . .things. He’s driven too fast, like my teen-ager has. And in the state of Texas, many people have guns in their car, I’m not condoning everything, but it’s not a major issue. [Because] when a person has bad character, it’s tough to change. But when a guy just gets into mischief, he tends to get into less as he gets older.”

The Rangers didn’t bring him here, however, because he’s mellowing. Exactly why they obtained him is debatable. “The one bad thing about the trade,” says the Morning News’ Rangers writer Gerry Fraley, “is it didn’t address any needs. It didn’t address defense or pitching. Which tells you, I think, that they made the trade to sell tickets. . . It made those luxury boxes in the new stadium [opening next season] easier to sell.”

Grieve, however, downplays Canseco’s marquee value, saying the trade had more to do with the length of his contract-since they felt they were getting a similar player to Reuben Sierra, and Sierra’s contract ended last season. “The main reason for the trade,” Grieve says, “is that he was signed for three years, at an attractive price. The fact that it may sell tickets, that’s just a byproduct.”

(Uh, yeah. Sure.)

What Grieve doesn’t say. but many others do, is that the trade got rid of someone, Sierra, who wanted the rewards of stardom without the pressures, someone who moped more than he inspired. His constant sulking was a destructive influence on other young Latin stars Juan Gonzalez and Ivan Rodriguez. In Canseco, however, the Rangers brought in a player who says he’s ready to step into the role of team leader.

It’s a role he did not play in Oakland. Canseco played on a team that went to three World Series, and he was only considered a piece of the talented puzzle. Rafael Palmeiro played with Canseco and his brother, Ozzie Canseco, when growing up in Miami, and-despite admitting that he didn’t think Jose would make it in the pros (“His brother was better”)-is Canseco’s best friend on the team. “In Oakland, there was a bit of jealousy from the other players,” Palmeiro says, “because sometimes when there’s a lot of stars on a team, there’s a lot of competition. But here, the guys love him. He’s a great guy. He’ll provide leadership in the clubhouse with his attitude to the game. And the players respect him for what he’s done in this league.”

“Having a leadership role on a team is based on what you’ve done on the field.” Canseco says. “By your consistency, your work habits. I’m not a rah-rah, boisterous guy. You lead by example.”

One also leads by communicating, and that is the least apparent but possibly most important contribution Canseco makes to the Rangers, according to almost everyone. Because he’s bilingual, he can be a Latin-Anglo bridge, critical on a team with so many Spanish-speaking players. “It should be easy for me, because I have a Latin background with an American upbringing. Plus, I can get along with everyone. Here, there are a lot fewer egos; people can be loose with you.”

Not that he needs to curb his own sizable ego, his cockiness. “Every great player has arrogance,” says ESPN and Rangers HSE broadcaster Norm Hitzges. “Reggie [Jackson], Michael [Jordan], Nolan [Ryan]. They are all cocksure. Jose is the same way. He loves the center stage. He loves the pressure. And I hope some of that swagger rubs off on guys like Juan Gonzalez and other Rangers.”

That swagger may be good for his baseball, but it’s also an integral part of his imposing image that scares a lot of people away. “I find more people respecting me than liking me,” he says. “Most people are intimidated by me-which is a form of respect. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s my fame, my size, what they hear about me. I just don’t know.

“Because I’m no different from anyone else,” he says as though no one has ever believed this. “I’m easygoing, and I have a good sense of humor.” Witness his comment to Oakland media that he was sent here from outer space to evaluate whether humans were worth living with (so far, no, he’d say). Or, in the clubhouse at Yankee Stadium, facing a media horde after visiting Madonna’s pad. when he popped one of her cassette tapes in the stereo system before answering questions. Or when his schnauzers burst into a manager’s meeting in the Rangers’ clubhouse.

“Hey,” Canseco yelled in mock terror. “Get out of there before you get me fired!”

IT’S LIKE MANAGING ELVIS. THAT’S THE way Tony La Russa, the Oakland A’s skipper, once described having to endure the distractions that nibble away at Canseco’s game. Dave Henderson, a former teammate, puts it in perspective: “It is not difficult to be Jose Canseco. It is impossible.”

Canseco meditates on this statement. “Often it’s very nice being me,” he says. “But, yeah, sometimes it’s tough being me. That’s what happens when you’re a superstar. And it can get outta hand. You come out of a bus, you’ve got no time to sign autographs, so someone gets mad and marks across your tailored suit. And some people say it shouldn’t matter because I’ve got so much money [a $23.5 million contract]. But that’s not the point. People should show respect. I’ve walked into the clubhouse and players have told me someone marked a big ’X’ across my back with a marker. That’s not right.”

It’s instances such as these that seem to have soured Canseco on grown-ups. He’s stopped trying to tell people who the Real Jose is because adults won’t listen. Outside the clubhouse or the batting cage, he seems most comfortable when surrounded by screaming youngsters.

“Jose has a big heart,” says Hitzges, “I can’t remember the last time he didn’t come out of the dugout 45 minutes early to sign autographs; because he knows that part of being Jose is signing autographs.”

It’s more than duty, Canseco says. “I love kids, to tell you the truth.” He has parties for them at his house, a la Michael Jackson. Once while with Oakland, Canseco was staying at the hotel adjacent to Arlington Stadium. He was playing quarterback with a bunch of kids in a game of swimming-pool football. Afterward he told everyone to get out of the pool, he was taking mem inside the hotel restaurant for lunch. He smiles remembering this-after 35 minutes, it’s the first smile of the session. “I had to get a head count for the waitress, and there were exactly 33 kids. My number. Pretty freaky.”

BILLY BLOOM HASN’T GIVEN UP. BUT it doesn’t look like he’ll get his autograph. Canseco’s been a little testy today, telling the kids firmly that there’s a time for everything, and he’s working right now, quit hounding him. He’s probably irritated at the breaks in concentration- from his batting-practice session, it appears his bat speed hasn’t returned yet. It should in time for tie home run bonanza everyone predicts he’ll unleash in the homer-friendly confines of Arlington Stadium. Still, even though he’s just taking cuts at the ball in the batting cage, people want to see a good show] and if Canseco disappoints them, you can see it sours him. But nobody wants to think his mood may keep them from getting their valuable chicken scratches,

Sure, he’d like to sign, make the kids happy; but re did talk about how unbelievable the demand for his autograph is, how he can’t sign all the time. Every time he gets within) 25 feet of the fence, even if he’s busy being instructed by coaches, the moaning starts: “Jose. Jose. Siiign this, pleeeze.” He usually keeps his humor about him, though. Early this particular morning, before the sunlight became irri-tatingly hoi, he joked with the kids. One dropped his program over the fence.

“Jose! Jose! Jose! Please pick up my program foi me, Jose!”

Canseco ambled over, gave it to him and smiled. “Nice try, kid. Seen it before.” The crowd laughed appreciatively. They love him. They follow him anywhere, Even try to scale the fence to get into the stadium during the photo shoot.

“Let’s got this over with,” he says, posing. “Remember, 10 minutes, ’cause I’m in a hurry.” It doesn’t look good for the autograph seekers.

The shoot over, Canseco heads off. By now the day’s practice is over, and me fans are thinning out. The autograph hounds must deal with their rejection. After all, superstars are very busy, and there are too many people out here to ever sign for all of them.

Actually, there’s no one out front. The fans have vanished.

Around he clubhouse, to the west side, and there hey are. A hundred or more. Single file along the fence, handing baseballs and pens one at a time through the gate. At the other end of the parking lot, walking away, is Billy and his family. Grandma is hugging him as he skips. Linda Bio 3m turns around, smiles, tells them to hold on. She walks across the parking lot.

“He got it.” She’s smiling and her eyes are red. Behind her, Canseco keeps signing, signing long after the Blooms leave for Atlanta, sigming one at a time until everyone is gore. By now the schnauzers are antsy. Proving people wrong takes a long time. Sometimes an entire hour. Sometimes a season. Sometimes a career.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Preview: How the Death of Its Subject Caused a Dallas Documentary to Shift Gears

Michael Rowley’s Racing Mister Fahrenheit, about the late Dallas businessman Bobby Haas, will premiere during the eight-day Dallas International Film Festival.

By Todd Jorgenson

Commercial Real Estate

What’s Behind DFW’s Outpatient Building Squeeze?

High costs and high demand have tenants looking in increasingly creative places.

By Will Maddox

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 2

It's time to start worrying.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo