AS NIGHT FALLS IN NEW YORK CITY-faster and darker than it does almost anywhere else-Elizabeth Peck Williams takes heart in a jaunty yellow crescent moon and a starry navy sky painted on a Broadway theater’s doors near her office.

“Roger has always said that from Day One he believed in three things,” Williams says. “One, that Carolyn was the right woman to be his wife. Two, that his Hor-chow Collection Catalog would be successful. And, three, that Crazy for You would be a hit.”

Williams is damned successful herself when it comes to making hits happen in die crazy world of Broadway investments. But her amusement this evening is packed with admiration for her co-producer, Roger Hor-chow.

As she speaks, the lights over at the Shu-bert Theatre flicker to life, brave against the dusk. In Manhattan, those tiny marquee bulbs warm the eager faces at the Shubert box office where that yellow moon and navy sky compose the logo of one of the hottest shows in town. Everyone in line hopes to buy a $65 returned ticket to see a sold-out story that is, in a phrase, purposely preposterous.

In Crazy for You, Bobby Child, scion of a family of financiers in 1930s New York, is banished by his mother to Deadrock, Nevada. His assignment is to stop being a child and be a Child: Clear his head of the-atrical-playboyish nonsense and prove he’s a chip off the old block by foreclosing on Deadrock’s Gaiety Theatre. In Deadrock he meets Polly Baker, the only girl in town and daughter of the Gaiety Theatre’s bankrupt owner. Polly hates the foreclosing Bobby. She likes him fine, however, when she doesn’t recognize him impersonating New York’s Flo Ziegfeldlike producer Bela Zangler. Bobby-as-Bela proposes, “Let’s put on a show!” to save the theater. Polly falls in love. Then the real Bela Zangler comes to tcwn.

“I didn’t want a message,” Horchow says without apology. “I wanted lots of dancing and singing. I wanted to recapture the days of Fred and Ginger.”

He got what he wanted, thought-free entertainment that climaxes in an exuberant dance number performed on a corrugated tin roof, a work so difficult that one dancer has had to leave the New York company because of the wear and tear on her ankles.

SO SECURE WAS HORCHOW’S BELIEF IN Crazy for You that he put up more than 90 percent of the $7.5 million it took to get it to the fabled Shubert Theatre stage-the boards on which A Chorus Line made history, Streisand made her Broadway debut, Hepburn made The Philadelphia Story a hit and Sondheim made good with A Little Night Music.

“We started at $7.5 million,” Horchow clarifies. That was $6 million for the Broadway show and 1.5 for [the pre-Broad-way tryout in] Washington. And I had set aside a million dollars for stupidity. I figured there were bound to be things we didn’t know about. There were. I had budgeted $600,000 for sets and $700,000 for costumes. It ended up $1.2 million for each. First time I saw the show in full dress, the curtain went up and I’d look at each woman’s outfit and say, ’Well, $12,433 just walked by.1 But they looked so good in those costumes.

“By the time we actually opened in New York, we’d spent $8.3 million. And I wasn’t planning to have any investors with me. But Elizabeth said she’d have to offer a few units to her usual backers. So I said I’d have to, too, to keep a few friends happy. A unit was $75,000. One percent. I told people we approached, LIf you want to do it, you’re going to lose all your money.’ “

The initial idea had been to simply do a revival of Girl Crazy. But then the Gershwin estate agreed to Williams’ suggestion of having Broadway playwright Ken Lud-wig (Lend Me a Tenor) create a “new” George and Ira Gershwin musical, one merely based on Girl Crazy.

“Roger announced that he wouldn’t be just an investor but the investor,” says Williams. “Now, that was a moment to remember.”

And so, by Horchovian standards, has been every moment ever since.

“SEE?” HE HOLDS UP A POCKET-SIZED 89-cent paperback memo pad, the kind you get at Drug Emporium. “This is my Little Red Book.” In it, 64-year-old Roger Horchow has painstakingly inscribed the scripture of his new life as a major Broadway producer, the statistical reports from each evening and matinee performance of Crazy for You since it opened at the Shubert on February 19, 1992. There, it took the coveted Tony Award for Best Musical, Broadway’s ultimate prize. Also a Tony for Susan Stro-man’s slap-happy choreography. Also one for William Ivey Long’s costume designs. And it gave Horchow the kind of nightly attendance reports that could make even the Shubert Organization’s wizened chieftain Bernie Jacobs weep: 101.8 percent of house-that includes standing room, “and they’ve accused us of hanging people from the chandeliers, too.” Williams laughs.

In time for the February opening of the Tokyo production of Crazy for You and the March opening of the London Crazy for You, let alone for the May opening in Dallas of the $4.5 million national roadshow version, Horchow learned to enter the contents of his Little Red Book into a Mac notebook computer, which he loves. It also holds the electronic catalog of his personal Gershwin recording collection. “But I still write each performance’s data down in here, too.”

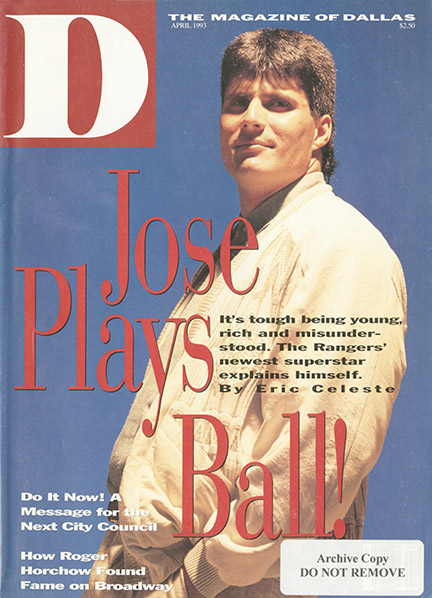

Roger Horchow is disarmingly unimpressed with himself. He opens the door himself for an interviewer-no staff to hide behind. He wears a simple sweater and shirt over khaki slacks. No wonder a couple of members of New York’s League of American Theatres and Producers have quietly grumbled, and only off the record, about this man who “got lucky-crazy’s the word, all right.” Horchow isn’t their kind of boy. No flash of rage, no dash of self-importance, no passionate odes to the Muse of Art. If he has an ego, it’s completely dedicated to hiding itself.

Nor do the usual denizens of New York have to worry-Horchow swears he won’t be back. He wanted to do this show. Period. Williams hopes, she says, that Sally, the youngest of Horchow’s three daughters, a 1992 Yale graduate and serious theater devotee, may in fact become a producer in her own right.

“Sally may be Roger’s greatest gift to us.”

’ELIZABETHS THE BRAINS BEHIND THE whole thing,” Horchow says. “After all, my dream really was always to see Girl Crazy redone.”

Girl Crazy is. in fact, a dreadful 1930s musical, the Gershwins’ ninth collaboration, notable only for having introduced Ethel Merman to Broadway and given Ginger Rogers her second strut down the Great White Way. In it, a New York playboy named Danny, not Bobby, is sent by his father to Custerville, Arizona, not Dead-rock, Nevada-in a taxi-where he meets Molly, not Polly, and ends up running a dude ranch, not a theater,

“But Elizabeth was always against Girl Crazy” Horchow says. “She said it was a terrible play, though we both agreed the music was wonderful, so it was only through her kind of negative attitude and our enthusiasm for the music that we decided to rewrite it. We decided together that it should be a farce-she was the one who brought the writer, the choreographer, the designers to us. It would have taken me five years to Find them all without Elizabeth.”

The result left a few critics grumbling about the show’s label, “The new Gershwin musical comedy.” Wrote Time magazine’s William A. Henry III: “Crazy for You was greeted with all but universal cheers last week, less for what the show is-a pleasant evening of well-loved songs and imaginative choreography hitched to a slow narrative, obvious jokes, completely undefined characters and mediocre performances- than for its shameless retrospection, its bland assertion that Broadway’s future lies in its past.”

And, in anticipation of just that kind of write-up. Horchow had been carefully instructed not to look for first editions of the newspapers on opening night; A bad review, he was counseled, could clear his post-show party in a hurry and make his cast suicidal.

“But my kids went for it,” he says, becoming suddenly animated. Probably it was budding producer Sally who nipped out of the Edison Hotel party, bravely walked the three blocks to The New York Times’ all-night lobby on West 43rd Street, put her 50 cents into what looks like the world’s biggest newspaper-dispensing box and came back to her father demanding he stop the party and read the review to the cast.

“The great thing,” he recalls in earnest, quiet wonder, “is that CNN was there taping. They showed it all over the world. People called me up from all over to say, ’I heard you droning on.” “

What CNN’s worldwide audience heard Horchow ’”droning” on about was the kind of Frank Rich review that could have made Merman herself crazy for Horchow:

“When future historians try to find the exact moment at which Broadway finally rose up to grab the musical back from the British, they just may conclude that the revolution began last night. The shot was fired at the Shubert Theatre, where a riotously entertaining show called Crazy for You uncorked the American musical’s classic blend of music, laughter, dancing, sentiment and showmanship with a freshness and confidence rarely seen during the Cats decade.”

Horchow stops for just a beat, recalling the moment. Something about the glamour of it all definitely has gotten through to him. Imagine reading to your shuddering cast of Broadway babies, on planet-wide TV, lines from The New York Times like, “As soon as the overture begins, you know that the creators of this show have new and thrilling ideas…” or the Daily News’1 “Crazy for You is an explosion of joy…1’ or the New York Post’s “the brass and the gold of Broadway are back!”

But only for a moment will Horchow indulge in what one of his show’s Gershwin tunes would call “Things Are Looking Up.” Something much closer to the second act’s “Nice Work If You Can Get It” seems to pervade the man. It’s as if he doesn’t quite dare to let himself believe his stunning show business victory over the odds. You get the feeling he fears somebody’s going to take it all back.

“1 don’t get excited very often.” he says, almost by way of apology.

“Look here,” he says as he suddenly hauls open the lap drawer of the desk in his North Dallas office-which he rents in another company’s suite, no sign of the Horchow name in the hallway.

“In here, I’ve got my roll of stamps. I’ve got my phone here. Answering machine, pens, pencils. I don’t need a secretary. Haven’t had one for years.” He adds graciously to his interviewer, “I’m probably not as busy as you.”

This man, five years ago, sold the Horchow Collection Catalog to Neiman Marcus.

For$II7 million.

A SCANT TWO YEARS AFTER CRAZY for You brought “Embraceable You,” “I Got Rhythm,” “Someone To Watch Over Me” and 16 other numbers to the Shubert-and won George Gershwin a Tony 55 years after his death-the story of Horchow’s boyhood brush with legend has become certified lore along the Great White Way. At either age 4 or 6, depending on which source you consult at the moment, Horchow was awakened in his family’s Cincinnati home by the sound of the piano downstairs. He’s still mystified by this heady occasion. “We lived in a very modest, brand-new subdivision,” he says, “not anything fancy. My dad was a lawyer in the Depression.” But his mom was a concert pianist. And somehow she had wooed George Gershwin to chez Horchow for a little post-concert soiree-just a couple of years before a brain tumor would kill him at the age of 38. Gershwin’s lyricist-brother, Ira, two years his senior, would live until 1983.

George Gershwin was born in 1898, in Brooklyn, started studying music at 13, began writing it at 16 and hit gold with a song called “Swanee”-Al Jolson sang it into the history books. Most of Gershwin’s 22 musical comedies defy revival today. Horchow can speak very knowledgeably about why. too. He knows that the American musical before Rodgers and Hammer-stein’s 1943 Oklahoma! was a vaudeville-inspired pastiche of dramatic scenes and songs. The story would stop, the actors would turn to face the audience, smile sweetly, nod to Mr. Conductor and deliver a ditty that had absolutely nothing to do with the evening’s plot- In working with Ken Ludwig, Horchow stressed that this presentational variety-show aspect of the Girl Crazy era had to go. He wanted a modern rewrite of a period musical-and he got it. So when Bobby and his Times Square girlfriends sing “I Can’t Be Bothered Now” in Crazy for You, there’s a reason-and it’s enhanced by one of the show’s most popular sight gags,

Gershwin’s compositional legacy is a mixture of the musicals-Of Thee I Sing is always attempted in election years and Oh, Kay! had an opulent but unsuccessful Broadway revival two years ago-and such jazz-informed piano and orchestral works as “American in Paris” and the “Piano Concerto in F.” Because of his theatrical “Tin Pan Alley” orientation, his work will never enjoy extensive respect from serious-music historians, but his lush, mood-wringing masterworks-“Rhapsody in Blue” and the folk opera Porgy and Bess, as deep in rhythmic and harmonic textures as the harbor of heavenly Charleston where it’s set- have come to serve as universal emissaries of “that American sound.”

IT STAYED IN HORCHOW’S HEAD. “THAT American sound,” when he became an Eagle Scout in 1942 (“I recently sent for this certificate,” he shyly shows the Boy Scouts document, then stuffs it back into a file of personal prizes); through his education at the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania; through college at Yale (“my dad at Yale lived in the same room that Cole Porter had”); and through three years in the Army. He learned to play piano on the same instrument Gershwin played in his living room (“1 play by ear in the key of C”) and has absolute pitch on a middle C.

But his was neither a musical nor a theatrical career.

Horchow, in fact, says he never felt entirely sure about what he wanted to do with his life and only “drifted” into retail.

In 1 953. his employers at Foley’s in Houston were amazed to find that their trainee-buyer in china, glassware and gifts could also iron a mean curtain. “In the OCS,” Officer Candidate School, “you had to iron uniforms. I worked with a woman who was a buyer. She said there was no way we could get the curtains ironed for the white sale the next day. I ironed them.”

Having risen from the rank of curtain-ironing trainee-buyer to buyer to vice president for mail order at Neiman Marcus by 1971-he’d married Carolyn Pfeifer in I960-Horchow decided to establish his own catalog operation. He’d watched how a catalog could become prey to its suppliers. “Estée Lauder could get two pages if she asked for it,” he says, because eustomers had learned to order her products by name. So he decided “never to use a supplier’s name or solicit money for a catalog- so I could pick what I wanted and write the copy any way I wanted.”

Horchow was hired by the Kenton Corporation to create the Kenton Collection, an upscale mail order catalog in 1971. Stanley Marcus told him no one would buy from a catalog called Horchow-advice he ignored in 1973 when he bought the mail order company with $1 million borrowed from friends and renamed it the Horchow Collection.

The Horchow Collection’s best seller was?

“Always the glass dessert set. Along with the expandable feather duster.”

The worst seller?

“An ice bucket shaped like a pumpkin, made of leather. Bought a hundred of them at $50. We unloaded them in a garage sale for $5 each. As a planter.”

When it was sold to Neiman Marcus Group, a subsidiary of General Cinema Corporation, in 1988. Horchow became chairman of NMG. Indeed. Horchow has presided over a vast collection of boards, most of diem nonprofit: American Friends of the British Museum, the Dallas chapter of the American Heart Association, the American Institute for Public Service, American Public Radio, the Better Business Bureau of Dallas, Dallas Museum of Art. Dedman College at SMU, the Texas Advisory Board of the Environmental Defense Fund, Friends of Art and Preservation in Embassies. KERA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Publications Committee (the Met needed help on its gift-shop catalog), the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Information Agency’s Private Sector Committee on the Arts, the White House Endowment Fund (“it raises money only for the public areas”), the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation’s National Advisory Council, World Wildlife Fund/Conservation Foundation’s Advisory Board and Yale University’s Development Board Executive Committee.

“I’ve got to get off some of these boards.”

But not even the din of such furious public service could sing down “that American sound” stuck in his head.

“Back in 1968,1 read in The Saturday Review of Literature about a complete Gershwin collection. I wrote and asked about it, but the man said it would cost a lot more than I could afford.” So Horchow began recording and trading Gershwin songs with a collector in Northampton. Massachusetts, the Gershwin expert he now refers to as “my pen pal.” one Frank E. luit. Now 83, Frank Tuit was rewarded by Horchow last year with a flight to New York, seats at Crazy for You and dinner with the Ho chows at Sardi’s.

“His wife said it added 10 years to his life.”

THE GERSHWIN PART OF HOR-chow’s Crazy coup, then, is easily traced, an omnipresent “Clap Yo’ Hands” love affair with the man’s music based on a childhood brush with brilliance. But how Horchow got from the pajamas of his late-night meeting with the great composer to the tux in which he accepted his Tony requires following a more circuitous path.

Even in today’s economy, where low interest rates caused investors to swamp mutual stock fund directors with more than $70 billion in cash last year, getting your hands on so creative a piece of financial possibility as a Broadway bonanza requires navigating it maze of Damon Runyonesque alleyways They lead from one private backer’s party to another, from one living room piano to the next bar, one evening’s cocktail party with a lyricist to the next afternoon’s tea with a composer-and at every stop you’ll find three scrubbed and scared chorus kids who think someone in the room wall “discover” mem if they sing Cy Coleman’s or Jule Styne’s or Bill Finn’s new thing extra well.

Despite the fabulous invalid’s hunger for infusions of capital, getting into the game requires everything but the password you might have used at a speakeasy, back in the Prohibition days when George Gershwin’s musicals were the kings of Times Square. Once you’re in, you can keep buying in again. You buy not only a piece of a new show’s action but the option to purchase “units” of me other productions that everyone hopes will happen as a result.

But until you’re in, you’re out. And Horchow almost didn’t get in.

“Years ago, I had put up money for New Faces,” an installment in the intermittent series of fresh-talent (and sometimes just green upstarts) revues, which Leonard Sill-man staged for decades on Broadway. “That show never came to pass. So I got my money back,” and was still only a would-be Broadway “angel,” as theater people call them. “But the person who had gotten me into that,” Horchow says, “was a local, a friend here in Dallas named Jane O’TooIe.

“She called up and said, ’Well, since we didn’t get to put our money into New Faces, there’re some people here raising money for a musical that’s in Paris called Les Misérables.’ “

Those people were Dallas’ Elise Murchi-son and Williams, who had gone to SMU for a year before studying art history at UT-Austin and Columbia University. Williams and Murchison were putting together a partnership for Les Miz.

“Well, these two ladies’ presentation was so excellent,’” Horchow says, “that I decided I would invest in a unit for SI 0,000. Jane and her husband didn’t want to do a whole unit, so I also took the other half of their unit. And that was my start.”

For $15,000, Horchow had bought into the London world première of Les Miz as we know it today. The Paris show had been an arena-style predecessor to the massive 3 1/4 hour staged musical spectacular that Cameron Mackintosh now has staged in 25 countries for more than 25 million people in a dozen languages.

“At that time [in the early 1980s],” Williams recalls, ’’a $10,000 unit seemed a risky, high investment. Just think-Les Miz at the Barbican” in London “cost 900,000 pounds to stage. By the time it came to New York” in 1985, “it cost $4.5 million.”

Williams today is developing a musical version of Dr. Zhivago with Lucy Simon, the composer of The Secret Gardens score. She also has plans for Vittorio de Sica’s Miracle in Milan-a show based both on the book and the film, with music by Manuel de Sica, the author’s son-and for a film of Texas writer Shelby Hearon’s Owning Jolene, “the story of a young woman, owned by everyone, as so many women feel at certain ages,” Williams says.

“Because of that first start with Elizabeth on Les Miz” Horchow says, “I was allowed to invest in Les Miz London, Les Miz New York, Les Miz Sidney, the roadshows and then Phantom [of the Opera]-five Les Mizes and five Phantoms” all under the producing leadership, of course, of Mackintosh.

’The thing is,” Horchow says. “I should have stopped while I was ahead, Because then I invested in the London Follies, where I only got half my money back. Then Into the Woods, where I only got about half. Gospel at Colonnus, where I got nothing back. lost it all. And The Secret Garden, where I’ve gotten, I guess, maybe half. The tour’s doing well, but I didn’t belong to the tour.”

AS WITH ANY PROPERTY DESTINED for the record books, good names already have attached themselves to Crazy for You, in addition to the pantheon of godlike Broadway designers-Robin Wagner (sets), William Ivey Long (costumes), Paul Gallo (lighting)-who put it on stage.

The role of Polly on Broadway was created by Jodi Benson, who led director Rob Marshall’s expressively edgy revival of Chess at Casa Mariana in 1991,

After exhaustive auditions on both sides of the Atlantic for the London production of Crazy for You, the role of Bobby went to Californian Kirby Ward because a Brit just couldn’t be found who could pull off the very American Gershwinisms that Harry Groener premiered on Broadway.

And the West End’s Polly is Ruthie Hen-shall, who has been romantically linked to Prince Edward. HRH Edward, younger brother to Charles and Andrew, as it happens, has worked extensively with Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Really Useful producing team and is referred to in London-knowingly or not. depending on who’s talking- as ’’the theatrical prince.”

The good news for Dallasites is that the première of the national tour of Crazy for You at the Music Hall in May will be led by Karen Ziemba, who was the chief attraction in both the New York and national touring productions of the Kander and Ebb revue, The World Goes ’Round and a heartbreaking Lizzie in the New York City Opera’s 110 in the Shade last fall. Ziemba’s Bobby will be played on tour by James Brennan of Me and My Girl.

With characteristic sensitivity, Horchow has made it possible for the May 12 performance at the Music Hall to be a charitable benefit chaired by Stanley and Linda Marcus for the Vogel Alcove, a project of the Dallas Jewish Coalition for the Homeless that provides child care for families residing in emergency shelters and transitional housing.

And, just as characteristic for the relaxed, gentle and unfazed Horchow is his delight in offering a parting joke-on himself.

“Ginger Rogers,” he says, “gave me the ultimate put-down, right in front of the cast. When she came to see the show on Broadway, I was slobbering over her, of course, and happened to say she did such a good job in Girl Crazy,” which opened in 1930, remember.

“She said, ’Oh, did you see me in it?’ “