The pickup rumbled along the isolated drive, June dust billowing behind Kenneth Aikman’s Ford as he approached his central Oklahoma ranch. From his window Aikman, just home from a day of welding, could survey his 175 acres and the cattle nibbling patches of grass not yet sunburned brown. Any other day he might have checked the sky for signs of rain. When a downpour comes, the square bales of hay sprawled like children’s blocks along his land must be moved inside or face ruin. Today, however, his sights were set on his skinny ranch-hand son, Troy.

The pickup rumbled along the isolated drive, June dust billowing behind Kenneth Aikman’s Ford as he approached his central Oklahoma ranch. From his window Aikman, just home from a day of welding, could survey his 175 acres and the cattle nibbling patches of grass not yet sunburned brown. Any other day he might have checked the sky for signs of rain. When a downpour comes, the square bales of hay sprawled like children’s blocks along his land must be moved inside or face ruin. Today, however, his sights were set on his skinny ranch-hand son, Troy.The senior Aikman walked into the house on the outskirts of Henryetta, a hamlet of just under 6,000, and announced to the 13-year-old: “I’ve got a job for you. You’re gonna weld. We’re going tonight to meet the man who runs the company.”

It had to sink in a minute. “Dad,” Troy replied, “I’ve never welded. I won’t know what to do.”

“You’ll do fine.”

That night at the welding site the man described the performance test to Troy. It was like speaking Spanish to a Swede. “It went in one ear and out the other,” Troy recalls. The man gave each Aikman a man quietly coached, so the man wouldn’t hear. “…Now, brush it off…” After several tense minutes, the boss examined the handiwork. “You start tomorrow,” he announced.

So began Troy Kenneth Aikman’s first paid job. The pattern of early responsibility had been set. It would continue through his ascension as an NFL pup of 22 to the Dallas Cowboys quarterback throne, from where former Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback and current CBS analyst Terry Bradshaw claims Aikman shall rule as the quarterback of the ’90s. How serendipitous was the storybook trek from hayseed welder to pro football paragon? Again his father gets the initial credit for Aikman’s career choice. “When we moved to Oklahoma, I wasn’t going to play football,” Aikman says. “I was going to play baseball and basketball. But the night they were signing up for eighth-grade football, my dad pulled up and yelled, ‘Are you going to play football? Because we need to take you down there.’ Even though he had never said anything, I knew how much it meant to him. He’s a country boy, and he likes the roughness of it [football]. So, knowing that, I went down there and started playing eighth grade football. Then ninth grade…” The rest, as they say, is statistics.

Most athletes don’t become stars. The odds of a boy growing up to be one of the 28 starting quarterbacks in the NFL are about one in 5 million. “But he always said he wanted to be a professional athlete,” says Aikman’s sister Tammy Powell. “So I always assumed that’s what he’d be.” Who could have known, though, that Dallas and Fort Worth would fall so completely for Aikman before he’d even completed a pass?

“Troy came to the Cowboys at a time when they [the fans] needed a hero,” says coach Jimmy Johnson. ’The Cowboys were last in the league. He was the All-American college quarterback, good-looking, single. And I think a lot of people in Dallas identified with Troy as the person who was going to help them bring back championships.”

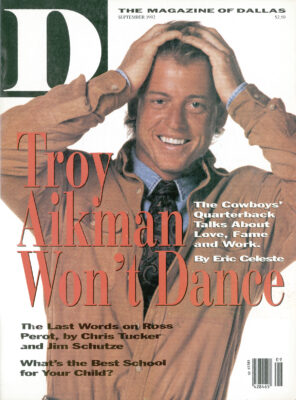

Troy the redeemer. An unfair and nigh impossible expectation placed on someone who will turn 26 in November. What’s interesting about The Adoration of Aikman is that, unlike many other star athletes, his private life shows that — for the most part — he actually deserves the attention. He’s all that he’s billed to be: quiet, serious, mature, kind, honest. And a country boy to boot, straight out of a Skeeter Hagler photograph. Pick up any profile, like the July interview in Inside Sports, and it will inevitably reiterate that point (“this snuff-dipping, truck-driving quarterback from rural Oklahoma…”).

But it’s dangerous to let surface impressions of Aikman become too firmly set. (He also drives an Acura Legend.) Just ask Oprah Winfrey. Her staff invited Aikman to appear on Winfrey’s show about “fantasy dates” clad in boots and jeans. They didn’t mention the other guests would be wearing suits. “They wanted to make me look like a hick,” Aikman says. “I understand, because I do wear that stuff — sometimes. But I’ve gotten tired of having to dress like that at every photo shoot just to confirm someone’s opinion of me.”

If you look only for a country cliché, Aikman will confound you. He’s a confident leader who is also remarkably shy; a kindhearted philanthropist with a petulant, stubborn streak; a man purposely sealed in a world with a few close friends who is nonetheless prone to fits of loneliness. As a defense, he’d be a tough read.

The key to Aikman is in his private life, the little-known acts that make up the real person. Writing personal thank-you notes to each of the 35 volunteers for his charity golf tournament. Sending a signed poster to a young quarterback in Odessa who is battling brain cancer. Giving thousands of dollars to a needy friend who called late at night, no questions asked, or to a former associate whose child was seriously ill. Sleeping with a Bible by the head of his bed.

A private life is defined by relationships, and looking at Aikman’s gives a picture of the man under the face mask. Looking at his relationships with the people close to him — his personal manager, his friends and family — as well as with the people who aren’t — Jimmy Johnson and sports columnist Skip Bayless — gives perhaps the best explanation of Aikman and his popularity, which Bayless has appropriately dubbed “Aikmania.”

“If you had told me that I would ever be working for a 26-year-old kid, a pro athlete, I would have laughed in your face,” says Verna Riddles, Aikman’s personal manager and former executive director of the Stars for Children charity. “But his honest desire to do something good for people, at his age — that impressed me.” Riddles now runs The Troy Aikman Foundation.

Riddles and Aikman have an interesting rapport. The no-nonsense way she handled Stars for Children since Aikman met her in 1989 led him to hire her to schedule his public appearances, photo shoots and travel plans, as well as to run a new charity that he formed. Riddles, 52, is one of the very few people who has become close to Aikman after he became famous. “We butt heads because we both have such strong personalities,” Aikman says. “But there’s no one better at what she does.”

It isn’t Riddles’ organizational skills that have forged this friendship; it’s her honesty. “It’s very difficult for me to really become friends with somebody, to allow them into this group of close friends,” Aikman says. “It takes a long time before I have that kind of trust with people. But once they do gain it, I would do everything in the world for every one of those people.”

And they for him. Riddles, who is married to an ex-coach, knows what pro athletes need: Someone who’ll step through the yes-men and tell them straight out when they’re right or wrong. Aikman can confide in her because he knows she looks out for his interests first. Plus she won’t laugh at him while he awkwardly practices two-stepping with her backstage at a Tanya Tucker concert. And she surely wouldn’t tell a reporter about the time he spent all day looking for a pair of black Levi’s and called her in frustration before Riddles found him a pair by phone. Unless, of course, she thought it would look good in print.

Friends who asked me about Aikman during my three months with him in the off-season were more interested in his love life than whether he and backup quarterback Steve Beuerlein get along. (They do.) And because he’s famous — public property — fans don’t always just talk; some get involved. “Last night I was eating at [a crowded restaurant] in Dallas and…it was the most sickening thing that’s ever happened to me,” Aikman says. “I’m eating, this woman comes up and just drops a napkin in front of me. I said, ‘Well, that was awfully demanding of you,’” and signed an autograph. I asked her, “‘Is that what you wanted?’ She says, ‘No, I wanted you.’” He raises his voice. “Then she comes down like she’s going to kiss me, I turn my head away — I’m not going to let her kiss me — so she licks me, clean across the face. While everyone in the place was watching. That is unbelievable.”

Aikman knows the price of fame — according to his contract, it’s $11.037 million over six years — and says he doesn’t ever want to give the impression he feels sorry for himself. He’s wealthy and healthy. “But, yes,” he says, “fame is a problem for me.”

Fame also could account for his marital status. “I want to get married,” he says. “I think marriage would be wonderful. If I met the right girl, I would get married tomorrow. If I was in love, I would have no problem putting aside the bachelor life.”

He continues on a wistful roll. “I think if you were with the right girl, marriage would be the most beautiful thing around.” Then, a long pause coupled with a faraway look, as if he’s rewinding a mental tape labeled Women I’ve Dated. “And if you’re with the wrong one, it would be the worst thing around.”

There are plenty of females clamoring for him. Just go to any public function where it’s known he’ll be, like his charity golf tournament in April — or his yearly off-season bash at Bill Bates’ ranch. Beauties everywhere. Hair everywhere, teased and moussed to Olympian heights. Makeup applied generously, busts exposed to the same degree. It looks like an audition for the television show “Studs.”

Sometimes it’s hard to ignore. Aikman gets revealing photos sent to his house. Women hand him their underwear to sign at restaurants. One lady even pulled up her shirt and asked Aikman to sign her rib cage. Sure it makes it easy to find a date when he wants to go to Borrowed Money. (“I don’t dance, though,” he warns. “I do not dance.”) But as Patrick Keegan, a close friend of Aikman’s from Tulsa, says: “You can’t be too aggressive [with Aikman]. If you squeeze Troy, he comes out the other end. And, because of his position, the kind of people he ends up meeting are not the kind he would marry.”

There’s the rub — and it’s the reason he is often lonely. “Troy is really searching for a great relationship,” Keegan says. Tom Whiteknight, a former UCLA player and one of Aikman’s closest friends, concurs. “He’s on top of the world, but he’s got no one to share it with.”

His finicky nature probably has as much to do with it as his fame. “I’m real picky about who I’m gonna date seriously,” Aikman says. “I’ve taken a lot of girls out, and I usually know by the end of the night if I’m interested.” Usually, he isn’t. He’s had few “serious” relationships since college. Now? “I’m very fickle,” he says. “And if you’re asking me what I want in a girl, I… I… I don’t know.”

Charlyn Aikman wants her son to be happy but realizes it might be a while before his romantic success matches his professional life. “Now I know,” she says, sighing, “why most pro athletes marry their high-school sweethearts.” They were the last ones to appreciate the superstar for himself, not his fame. His old friends still see Aikman the same way Charlyn remembers her son: as the one who collected baseball cards; the youngest of three offspring; the one who used to listen not to Hank Jr. and Clint Black, but to Ted Nugent. (“Ted Nugent? No, no. She’s thinking about my sister,” Aikman says, laughing. “I was the Eagles.”)

Aikman is protective of his family. His mom and dad recently reunited after a two-year separation; one sister, Terri, has two kids; another sister, Tammy, is married and has a newborn. He’s the same way about his friends. They act as his cocoon. His friends say the primary reason Aikman will never be the “arrogant jerk” many pro stars become is because his family keeps him grounded.

“He’s still real generous,” Tammy says, getting ready to go to a resort where Aikman is taking the entire family for the Fourth of July. “I don’t see that he’s changed except that he’s becoming a lot more like my dad. He’s become good at tuning people out. And he gets irritated, but he doesn’t lose it like my father would. He keeps it under control.”

The control he gets from his mother. She keeps him levelheaded and humble. Charlyn Aikman moved to Grapevine after she and her husband separated during Aikman’s rookie year. Now they’re back together, and Aikman is building them a ranch in McKinney so they’ll be nearby. (They didn’t tell the ranch Realtors it was Aikman buying the property, fearing the price might increase dramatically.) Even though Aikman says he can tell her anything, it’s likely his mother has had to develop an immunity to fans’ brazenness. She opens all her son’s mail.

If his family keeps Aikman’s feet planted firmly, then his friends are his social liberators. He usually becomes closest to extroverts who help ease his shyness, like Babe Laufenberg, the glib former NFL journeyman and current Cowboys radio broadcaster who became friends with Aikman during Laufenberg’s two years in Dallas, 1989 and 1990. In the football business, though, it’s unwise to become too attached, because often you’ll discover your partner’s locker cleaned and emptied, which has happened to many of Aikman’s friends.

“Yeah, it’s part of the business,” Aikman says the same day tight end Rob Await, a good friend, left Dallas for the Denver Broncos. “My rookie year, I was just hoping to be friends with anybody, and I became close to a lot of people who didn’t stay with the team. And it was tough. That was my first acclimation to the NFL, how it was run as a business. But if [a team] looks at it from that standpoint only, then you don’t have any emotion in the game. I think for teams to be successful, there’s got to be a bond between players, a sense of family. … I’ve had a different roommate every year. I might room with myself this year, so I don’t lose another friend.” He’s only half-joking. Friendships are important, his lifeline to the real (non-football) world. He tries to stay in touch with not only old teammates and coaches, but pals from Oklahoma and California where he grew up. To help lift the pressure Aikman places on his shoulders, his boisterous buddies make a point of loosening him up, making him laugh. “He’s impressed with people who are outgoing,” Riddles says. “He wants to be like that.” Which may explain why he gets along with Channel 8 sports anchor Dale Hansen so well. Aikman lights up whenever the merry, wisecracking Hansen walks into the room.

Aikman’s best friends, Doug Kline and Tom Whiteknight, were teammates with Aikman at UCLA, and both live in Dallas. “It’s a great relationship for Troy with Doug and Tom,” says Pat Keegan, who at one time has helped all three get jobs with beer distributors. “Troy gets to talk to them about their girlfriends, their truck problems. It brings a sense of normalcy to his life.” Before one midday interview, Aikman got a call from Kline as he was walking out the door. The call took 20 minutes. “Sorry,” Aikman said sheepishly. “Had to get caught up on all the news.”

Even on the phone, though, Aikman is quiet. He does very little of the talking. “He’s on the quiet side if you don’t know him,” Laufenberg says. “So we’re perceived as being opposites, but we actually have a lot in common. He does have a good sense of humor.”

It’s true that Aikman’s funny bone isn’t struck often in public, during games or interviews, where fans might get a sense that he might be enjoying his good fortune. “The one thing people say to me,” Riddles says, “is that they wish he’d smile more.” Aikman can be stoic, pensive, even moody. He can be brusque with fans. When answering questions, he has a routine. He looks you square in the eye like you’re an idiot, pauses, then finally gives a thoughtful, reasoned response. During an interview at Jason’s Deli in Irving, a middle-aged fan walked in front of Aikman to get his attention. Aikman ignored him until he finished his response, then turned to the man.

“Hi,” Aikman said.

“Hi!” Awkward pause.

“Can I help you?”

“Uh, no. I just wanted to meet you.” Aikman nodded. The man seemed disappointed. “You’ve got a lot of fans.”

“Thank you.” Another pause. Mercifully, the fan left.

Aikman also grows irritated if something he feels is important doesn’t go his way — like when the other pro athletes at his golf tournament didn’t receive all the gifts originally planned. He gets prickly if he thinks people arc taking advantage of his cooperation. “I had to jump all over those NFL people who came to shoot my football card,” he says during a photo shoot for Inside Sports. “They told me they’d need an hour or two, then they show up and want all day. I said, ‘You’ve got an hour, period. I’ve got guests [the band Shenandoah].’” The IS photographer got the message. That shoot lasted 10 minutes.

“There are always people who will burn you when you’re in his position,” Laufenberg says. “So he’s just guarded around people he doesn’t know.” True. During our first meeting at Valley Ranch, he was serious, quiet, noncommittal. Barely spoke three words. Three months later, during our last interview at Valley Ranch, Aikman walked in singing (but not dancing to) the song “Achy Breaky Heart.” He grinned. “Man, I’m sooooo sick of that song,” he said, plopping his feet on the table.

Even when he does open up like that, when he’s loose, Aikman’s humor is not easy to detect. He appreciates irony. Just mention Cowboys center Mark Stepnoski, who delights in sarcasm, and an appreciative, wry smile comes to Aikman’s face. He shares Stepnoski’s penchant for pointing out dumb questions to reporters by answering them literally. You had two sisters, right? “Still do, I’m pretty sure.” Do you want kids? Marriage? “Think I want it the other way: marriage before the kids.”

Other public reactions can be more subtle but no less weird. While buying a guitar stand and a by-the-numbers guitar primer (the drummer from the country band Shenandoah gave Aikman his guitar as a gift; Aikman later discovered his fingers are too big to stay on one chord), the music store clerk couldn’t decide whether to call him “Troy” or “Mr. Aikman.” So he compromised. “Hey!” he yelled to his manager. “Does Mr. Troy get a discount here?” It made the manager laugh, and must make Aikman wonder. He doesn’t understand why people act that way. He sees himself as overwhelmingly normal, a guy with the same faults and vices as anyone his age. “Hey!” Laufenberg warns. “Don’t paint this guy to be a saint!” Aikman would certainly smile at that.

Ok, Aikman’s not a saint, even if he was born just outside the City of Angels, in the Los Angeles-area burg of West Covina. A modest, popular student, he eschewed the surfer dude beaches for another honored California sphere: jock-dam — the diamonds for baseball, the courts for basketball. “Everything I did with sports growing up came easily to me.”

Baseball was king on the coast. Aikman fancied himself a future star. (After high school, Aikman, a pitcher with a 92-mph fastball, would tell the New York Mets it would take “oh, I guess, $200,000” to sign him to a pro contract. “Good luck playing football,” came the reply.)

Aikman loved the LA area. He could ride his bike to the YMCA and play basketball. When he moved to the nearby suburb of Cerritos, he could see the parachute jumps at Knott’s Berry Farm theme park from his back porch. A boy’s life.

Then the family moved to the spacious ranch just outside of Henryetta, Oklahoma, when Aikman was 12, and his life was rearranged. He was less than thrilled. “Where are we?” was Aikman’s first reaction. “We were 8 miles outside of town, on a dirt road — we were suddenly country. It was a big adjustment … a whole different life. But after about four months, I really liked it. I came to appreciate that simple lifestyle a lot more. People just seem to be so much more genuine.”

Aikman learned to hunt with his dad. He would water ski at Lake Eufaula, even fish once in a while. He didn’t go to the lake to party on weekends with many of the other Henryetta teens; he preferred cruising Main Street on Friday and Saturday nights.

High-school football fans quickly got to know the quarterback for the Fightin’ Hens of Henryetta as the tall, relatively thin kid with the strong right arm stirred up the town with his fall heroics. By his senior year, the entire football-whipped state of Oklahoma knew all about Aikman, who led a team with poor talent to a 6-4 record, only the school’s fourth winning record in 25 years. He was selected All-State. Even so, only a handful of schools showed interest. Despite what they told him, the University of Oklahoma and then coach Barry Switzer only offered him a scholarship, Aikman says, to keep him away from cross-state rival Oklahoma State.

“If I met the right girl,” Aikman says, “I would get married tomorrow. I would have no problem putting away the bachelor life.”

If that was the case, it wasn’t the last time Switzer was less than honest with Aikman. Oklahoma stayed with its running game, which didn’t develop or showcase Aikman as a quarterback. And big-time OU football had another aspect Aikman found distasteful: the symbiotic relationship between the city of Norman and its football team. “It’s ridiculous,” Aikman says. “OU football players are 19 years old, and they get carte blanche treatment everywhere they go in the city.”

Unless they’re injured. That’s what happened to Aikman his sophomore year, when he broke his leg against a Miami team coached by Jimmy Johnson. Switzer helped Aikman transfer to UCLA, but during that summer, while Aikman waited to go back to the West Coast for the fall semester, he had reason to worry that his football career could be over. He knew he needed to prepare in case the leg injury never healed properly. Aikman’s family was by no means wealthy. He needed a summer job.

Problem was he was a pigskin pariah, a defrocked Sooner football star. “I don’t know if this sounds right, but once Troy decided to transfer to UCLA, he was basically unhirable,” Pat Keegan remembers. “No one gave a shit up here.” So Barry Switzer finally called Keegan, who ran a distributorship for Miller Beer in Tulsa, to see if he had any work for Aikman. Keegan said he’d take a look.

“I pulled in and Troy was waiting for me at my office,” Keegan says. “I came in, chatted with him a few minutes, we got a cup of coffee and sat down, and, well, it doesn’t take me all day to look at a horseshoe. He was just such a great kid with warm, endearing qualities.” He was also big enough to haul a keg, if need be. He got the job.

He hoped his return to the West Coast would change his recent hard luck. He didn’t get off to the best start, however. He had assumed he could study business at UCLA, just as he had at OU. But when Aikman tried to register as a business major he learned UCLA didn’t even have an undergraduate business school. He settled for sociology. (Aikman’s still three courses short of a degree; he’s interested in finishing, when he finds the time.)

After sitting out a year due to NCAA rules governing transfer eligibility, he reintroduced himself to football fans. He set school and conference records his junior and senior years and was a Heisman Trophy candidate, adorning many national sports magazine covers. He led UCLA to a Cotton Bowl victory over Arkansas his senior year, capping a season in which he managed to live up to the Heisman Hype. He struck a friendship with UCLA coach Terry Donahue. The coach wasn’t always kind to Aikman — he often chewed him out for on-the-field mistakes — but Aikman says he was always honest with him, which he respected. Off the field, he forgot about the Eagles and instead pumped country music from his radio. Aikman, Keegan (who moved to LA when his wife, TV broadcaster Becky Dixon, was transferred by ABC Sports), Kline and Whiteknight spent free time barbecuing on the cramped balcony of an off-campus apartment, listening to Randy Travis. “The neighbors really thought the hicks had hit town,” says Aikman, laughing.

Once it was understood that he would be the first pick in the 1989 draft, Aikman began scanning the bottom of the NFL standings. There were two teams who were the most bruised of the crop: the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers. Late in the season, it looked as though Green Bay would hold the rights to draft Aikman. He asked Kline if he would move to Wisconsin with him. “Hell, no,” Kline said. “I’m movin’ to Dallas.” Soon after. Aikman was in the stands when Green Bay lost the rights to draft him by winning its last game of the season against the Phoenix Cardinals. No one was cheering louder than Aikman. The Cowboys had the first pick. He, too, was movin’ to Dallas.

Aikman carried a plastic trash bag around his Westwood apartment gathering up the items that needed to be moved to Dallas. He had signed a contract after meeting Cowboys owner Jerry Jones at the first Stars for Children golf tourney, hammering out the deal that evening. Aikman was going to miss the rest of his spring ’89 classes to get settled in Texas and work out in minicamps. Pat Keegan watched Aikman as he took a last look around his apartment. “Might need these, too,” Aikman said matter-of-factly as he unscrewed light bulbs he had bought. Keegan just smiled.

Aikman’s always been frugal. Those close to him say his careful nature coupled with the sound counsel of agent Leigh Steinberg have led to wise investments. In fact, his finances were the only area of his shiny new metallic blue career that Aikman could control his rookie year. For even though he was ecstatic — giddy, even — at the prospects of beginning his career in Dallas, the first season was pregnant with all the irony and frustration of a Dwight Yoakam lyric: Another lesson about a naive fool/That came to Babylon/And found out that the pie don’t taste so sweet.

“That’s exactly how it was,” Aikman says. “I expected the pie to taste a little sweeter, but it was the worst season I have ever experienced.”

The campaign’s bitter flavor began well before the pitiful final tally showed the Cowboys with one win, 15 losses. It began during the summer, soon after Aikman arrived in Big D, when coach Jimmy Johnson drafted his former quarterback from Miami, Steve Walsh. Everyone tried to persuade Aikman that Johnson and owner Jerry Jones selected Walsh only as trade bait for more draft picks or better players. “But Troy took it personally,” says a friend. “I think Troy looked at that as a vote of [no] confidence.”

That began the strange, tense relationship between Johnson and Aikman. It’s long been apparent that there is an uneasiness between the two, and Aikman admits that it originated with the Walsh acquisition. It seems that not only did Johnson not want to play favorites, therefore deciding not to give much praise or consolation to either quarterback, but he also was misled by Aikman’s cool demeanor. Even the quiet, assured star could have used a little coach-like stroking. Yet even after Walsh was traded to New Orleans, communication problems, to be delicate, remained.

You won’t get either one to admit it on record. “Troy and I have no problems,” Johnson says with an isn’t-that-a-stupid-question scowl. “That’s been created by the media.” Aikman, for his part, doesn’t want a public dialogue that would serve only to make his day at the office that much harder. But friends acknowledge that, at the least, Aikman doesn’t believe Johnson is always honest with him. For Aikman, who waxes at length about the necessity of trust and respect in every relationship, dishonesty is the fatal flaw. Says someone close to Aikman: ‘Troy doesn’t trust him [Johnson] as far as he can throw him.” Given Aikman’s world-class right arm, that’s saying something.

Another example of that strain was seen in last year’s mangled situation with Steve Beuerlein, the Cowboys’ well-regarded backup quarterback. Aikman was injured during the season’s 12th game against Washington. Beuerlein finished that victory and quarterbacked the team to five more consecutive wins, including a playoff game against the Chicago Bears. During that streak, Johnson reportedly told Aikman that he would start when he felt ready. Reporters would then ask Aikman whether he would play that week. “I expect to start, yes,” would be his reply. Johnson would then tell the sports scribes that no, Aikman was not ready. Reporters ping-ponged back to Aikman, who was said to be unhappy and confused in the next day’s headlines. The hard feelings linger with Aikman.

It’s a classic football battle: quarterback vs. coach. From Pittsburgh’s Terry Bradshaw and Chuck Noll to Denver’s John Elway and Dan Reeves, headstrong QBs have clashed with strong-willed coaches. But then again the four people above have led those teams to nine Super Bowl appearances; such disputes tend to dissipate when the team enjoys success.

Nevertheless, it’s an unfortunate personal dynamic between Aikman and Johnson because they do admire each other’s professional drive. Each understands the physical and time-consuming demands that must be met to excel in the NFL, and each embraces those demands with gusto. Aikman stays in shape — he’s even more pumped, more of a “quarterbacker” (half quarterback, half linebacker) this year than before. Players say he’s never looked more confident on the field. And Johnson, well, he’s a prime heart attack candidate; he obsesses about the game. “As a football coach he’s extremely driven,” Aikman says. “His competitive nature is why he’s so good, and why he wants [to win] so bad.”

Aikman, too, has the competitive drive, the stubborn refusal to accept defeat — although that quality isn’t overtly displayed. “Nothing fazes him,” says Cowboys fullback Daryl Johnston. “The way he practices, the way he carries himself, the way he handles the media, the time he spends with charity — he handles it all so well, so calmly. But he’s still one of the most competitive people I’ve ever met. He wants to win so badly.”

Johnson doesn’t let conventional wisdom dictate whether he keeps a player. But if he did listen to outsiders, he would find many who praise Aikman. Chicago Bears coach Mike Ditka upset his quarterback, Jim Harbaugh, when he showed Harbaugh a tape of Aikman in hopes Harbaugh would emulate the Dallas quarterback. Former Philadelphia Eagles coach Buddy Ryan heaped praise on Aikman in the same sentences in which he derided Johnson. Former All-Pro quarterback Dan Fouts even selected Aikman as one of his quarterbacks on Fouts’ fantasy league team last season.

Locally, Dale Hansen has been accused of running an underground Troy Aikman fan club, while Dallas Morning News columnist Randy Galloway also takes a shine to Aikman. Captain America himself, former Dallas quarterback Roger Staubach, said recently, “If I had to choose a quarterback to start a team right now, I’d take Aikman.” His most vocal critic — really the only authority who has anything bad to say about his game — is Skip Bayless.

Some teammates scoff. “Troy has that leadership ability you just can’t turn on and off. It’s in his blood,” says offensive lineman Kevin Gogan. “When he came here, he just took over. Maybe he wasn’t trying to, but it was there anyway. We had no one pointing us in the right direction. He was the right person to take over. You don’t have to talk all the time to be a great leader. And he usually leads by example. But he’s not that quiet. Mark [Stepnoski] and I started calling him ‘Frontsie’ because he’ll jump in front of your face and tell you real quick if you’re not doing something right.”

Bayless, for his part, says he’s just telling fans the truth, even if they don’t want to hear it. “I hope you tell Troy this, because I’d tell him if I could,” Bayless says. “I fear getting close to Troy Aikman, because I like Troy Aikman a lot — he seems to be a wonderful person. But to keep my objectivity, to be able to tell fans some of the criticisms that Cowboys coaches tell me anonymously, I have to keep my distance.” What Bayless didn’t tell fans, though, was about a bet he lost to Dale Hansen. Bayless bet Hansen a steak dinner that Aikman would not make All-Pro, which he did this past year.

“Skip keeps making exceptions,” Aikman says. “I shouldn’t be starting in Dallas, and now I’m starting, and then I’m not as good as I was supposed to have been, and I make the Pro Bowl; with him it never ends. We could win the Super Bowl, and with him it’s ‘OK, you were supposed to win five [Super Bowls].’ Well, sorry Skip, I’ll see what I can do.

“It’s almost like a vendetta. There’s very few days where I’ve picked up his column and he hasn’t taken a shot at me. It’s gotten to the point that it’s funny because it’s so absurd.”

“Troy has a surprisingly fragile psyche,” Bayless replies, “and it shows in how much he cares about what I write. He shouldn’t care at all what I say! But it’s those kind of chinks in his star-covered armor that make me hesitant to say he can lead this team to the playoffs. Maybe he can. Everyone at training camp is talking about the ‘new Troy’ — how confident and relaxed he is. If he does lead them to the playoffs, no one will sing Troy Aikman’s praises louder than me. But I — and some skeptical Cowboys coaches — will just have to wait and see, because he hasn’t yet lived up to his status as the number one pick in the draft”

Get Aikman started on the media in general, and he’ll run awhile. “I have a lot of friends in the media, a lot of people I respect. But it’s amazing the [lack of] knowledge of the people that cover our game,” he says. “And I’m not a guy who hates the media. But I think sometimes they need to be a little more understanding of our demands. I don’t play football to give them a story. I play to win the game.”

As he talks about why he plays, an example of the Aikman Effect takes place behind him. Two groundskeepers at the Hackberry Creek Country Club are outside the enormous window, doling out work duties. One notices Aikman, and keeps looking over the other worker’s shoulder, nodding to the other as if he’s listening. They split up, and the groundskeeper who has spotted Aikman trudges off to clean the pool, looking back several times as he wipes sweat from his forehead. Once he reaches the pool, he suddenly springs to life. He grabs a round ball. He hikes it to himself, takes three steps back, dodges a couple of imaginary defenders, and lets loose a throw into the pool. His arms go up straight up. Touchdown.

Daydreams of football glory are luxury for most, but they’re essential for 15-year-old Josh Batte. Batte was a star quarterback in Odessa, the West Texas football-lovin’ town of Friday Night Lights fame. Josh, who broke many freshman passing records, was being groomed to become Permian High’s next star. Then he began to veer to the left when he ran. He complained of dizziness and headaches. Soon after, Josh was diagnosed with brain cancer. In February and March, he had operations to remove tumors before undergoing radiation therapy.

Meanwhile, after a March minicamp practice, Aikman walked into the locker room, feeling rambunctious. Cowboys public relations man Dave Pelletier handed Aikman a rolled-up poster; Aikman yanked it out of his hand, whacked Pelletier on top of the head with it and laughed. He unrolled the poster, took Pelletier’s black felt-tip pen and stared at the poster a long time. He finally wrote a few sentences, carefully rolled it back up, handed it to Pelletier, sighed and headed to the showers.

Months later Josh’s mother, Toni, still sounds excited about the framed, signed poster of Troy Aikman above her son’s bed. “It was a thrill for Josh to get that poster; it was a thrill for all of us,” she says. “We felt very taken by Troy and everyone involved taking the time to do that. It really is special for Josh. Every time he looks at it, it’s an encouragement. It lets him know that even if the odds are difficult, you can come back.”

The ability to help people is what Aikman likes most about his fame in Dallas. (Although, he admits, he’d like to be able to see the effect of his fund-raising and appearance time. “Too often, pro athletes don’t see that, and they end up feeling like prostitutes, used just for their name.”)

The less important aspects of fame are still present. He’s on talk shows, featured in magazine profiles, he graces the covers of many national magazines. But he knows that’s a product of the team’s success and prognostications that say the Cowboys are Super Bowl contenders this year. That will be important to him once the season starts, but not right now. The things he’s concerned with aren’t the obscure facts debated ad nauseam on the sports talk shows. He wonders if he’ll ever be able to play a song on that guitar he was given. He wishes he could have had a few more barbecues on his back porch during the off-season, but maybe next year. He hopes his parents stay happy, together or not. And he wants to make sure he doesn’t get so caught up in the hype that he can’t listen to Shenandoah, drink a beer and jam with his friends.

He was doing just that during his last bash of the off-season at Cowboys safety Bill Bates’ ranch north of Dallas. It’s hard to tell why he was so happy there, why he was so at ease. Maybe it was the band, maybe the women who egged him to dance with them. Maybe it’s because he started talking to his college sweetheart again — the one who knew him back when. For whatever reason, he was open and alive that night, allowing himself more fun than he can have once the season starts. The band was blasting, the lights were low and you could hear Aikman whooping. In fact, if you looked to the front of the stage you could spot him in his floral print shirt and tight Levi’s. And although it was dark and he was surrounded by friends and women clamoring for his attention, you could see his legs and hips swiveling, his boots scooting, his left hand trying in vain not to spill his cup of beer and his big right arm pumping the air. If you didn’t know better, you would swear he was dancing.

Get the ItList Newsletter

Be the first to know about Dallas' best events, contests, giveaways, and happenings each month.