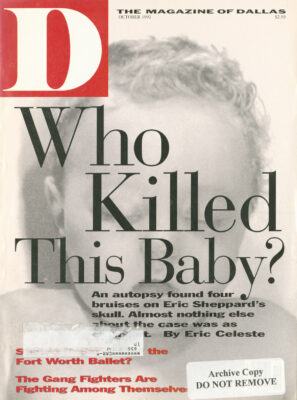

EVELYN LANKFORD SAT ON the floor wailing as her neighbor frantically massaged 9-month-old Eric Sheppard’s tiny, pale chest. Lankford, Eric’s babysitter, had tried CPR minutes earlier after the baby had gone into convulsions at her house. She then rushed the child next door. The paramedics arrived and continued to work on Eric Sheppard en route to the hospital.

There it became official; He died at 4:50 p.m., June 17, 1991.

Two months later, the Dallas County medical examiner made his own declaration: Baby Eric was murdered. Beaten on the head at least four times. Beaten just before he died. And the child had been with Lankford the last six hours of his life.

Three days later, on August 15, Lankford was charged with murder; the newscasts showed her being led away in handcuffs. A grand jury indicted Lankford in January, and the April trial lasted eight days. During closing arguments, the state gave the jurors an impassioned plea: Deliver justice for baby Eric.

Without a mumble or whisper, the jury went into deliberations. Il took them 10 minutes to reach a verdict: Not guilty.

There were no TV cameras when the decision was announced, nothing to record Evelyn Lankford’s jubilation, the prosecutor’s pained look, the surprising absence of baby Eric’s parents, the thankful prayers of Lankford’s friends. All that remained were the obvious questions. If not Lankford, who? And how had this happened?

It appears these questions will never be put to another jury. The district attorney’s office says it put the right person on trial, and it has no intention of charging anyone else with the baby’s death- But the trial brought out disturbing evidence that, according to the defense team and most jurors, shows the wrong person was tried. If anything, the strange, sad tale of the baby’s death shows that there were actually two victims in this case: Eric Sheppard and Evelyn Lankford.

EVELYN LANKFORD WAS WALKING down her quiet, lower middle-class residential street in Balch Springs one Sunday morning three years ago when her life changed. She had always been a kind person, say friends, but up to that point the problems in her family-her mother had just died from cancer, her husband was chronically ill-had consumed her and left her discouraged. Then she walked into the Cathedral of Life Full Gospel Church at the end of her block “because I knew that’s where you found peace.”

She found guidance and purpose for her days, spending her free time at the church. She was one of four members who would take turns watching children in the nursery during Tuesday and Thursday evening Bible classes. Her love of children was soon apparent. “She’s like a big teddy bear,” says church elder Tony McNeal. “When you see her with children, she has such a humble spirit, it just reaches out and touches you.”

Just a few years earlier, the Lankfords had adopted a niece’s two neglected children: Amanda, 5, and Chris, 3. Because her husband couldn’t work and they had the two young children to raise, Lankford decided to supplement her job cleaning houses and apartments with babysitting. In January 1991, she put an ad in the paper and waited. Within a few days, Roxie Edwards called. Edwards had tried to find a good babysitter for her son, Eric Sheppard, but that had been difficult. Eric, although healthy in appearance, needed special attention because the red-haired youngster was often sick.

For Edwards, Lankford, now 42, proved to be more than just a good sitter. She was a friend who didn’t mind counseling her. When Lankford discovered the baby was already on whole milk at four months, she convinced Edwards to put Eric on formula; she also bought a better bottle to keep him from throwing up so much. Lankford helped console her the many times Roxie called crying after an argument with the baby’s father, Jack Sheppard (Edwards and Sheppard were not married until shortly before the trial). And Lankford watched with growing concern as baby Eric seemed to hurt himself continually-she often saw Eric with bruises that Edwards explained as the results of accidents.

Twice during the six months that Lankford watched Eric she tried to give up babysitting; she needed more money and wanted to work two full-time jobs. Both times Edwards pleaded with Lankford to watch the baby. No one else would, Edwards said, because the child was sick so often. She offered more money to Lankford. Lankford was torn. She knew how tough it was to find a good babysitter-she had even let Edwards watch her children one day, but never took them again because Edwards spanked her 2-year-old. Both times she acquiesced. They were the most fateful decisions of her life.

“IT WAS A DAY LIKE ANY DAY,” SAYS Lankford.

June 17, Edwards called Lankford at about 9 a.m. and said she was in a hurry and running late. She and Jack Sheppard managed a Dependable Mini-Storage in Mesquite; they lived on-site in an apartment provided by the company. (Edwards and Sheppard declined to talk to D Magazine.)

Edwards arrived with Eric shortly after 9 a.m., the baby clad in a shirt and a diaper. Lankford contends that the baby had purplish-blue circles like bruises under his eyes. (The autopsy reported no signs of discoloration.) “Oh, no, Roxie, not again,” Lankford said. She took the baby. He was “splotchy,” droopy-eyed and cold to the touch. “He’s been in the car with the air conditioner running,” Edwards said. Lankford remarked that Eric was groggy, unresponsive. She told Edwards he should see a doctor. “I’ve got to get my books to balance at work,” Edwards replied. Eric had been teeming, she said, and hadn’t been sleeping much. “He’s been driving me crazy,” Lankford remembered Edwards saying. Edwards stayed a few minutes then rose to leave. Lankford says Edwards waved to Eric. “Say bye-bye. Say bye-bye.” Eric didn’t wave back and Lankford tried to coax him. “Say bye-bye to Mommy, Eric.” After a few minutes, Lankford says, she lifted Eric’s arm herself and waved goodbye to Edwards.

That day Lankford was also watching her own two children and her grandchild, Justin. But she concentrated on Eric. Shortly before lunch, he began to cry, and Lankford looked for his teething tablets in his baby bag. Instead she found a medicinal liquid that read 11 percent alcohol, lankford called Edwards and said it didn’t seem right to give him something with that much alcohol. Edwards said she’d given it to him all weekend and to give him his medicine.

Lankford rubbed it on his gums. Then she fixed lunch for everyone. She warmed three jars of baby food: one meat, one vegetable, one fruit. Eric-already a size 4 and 30 inches tall-was a healthy eater. That day, however, he fell asleep in his high chair, not touching his food. So she laid him down to sleep, one monitor next to the bed, another in the living room.

Lankford says she then walked into the living room and found Jack sitting on a chair. (Jack later said he never entered the house.) Jack said he wanted to get her neighbors’ dog, a Doberman pinscher that had been taken in as a stray. Lankford and Sheppard walked next door, looked at the dog in the back yard, went back to Lankford’s and called the neighbors. The owner told Jack he could have the dog. Jack left.

About 2:30, Lankford heard Eric crying on the monitor. She reheated the baby food, changed Eric’s diaper and tried to feed him; he wouldn’t eat much. She sat him down on the floor. He saw a cord-he loved to play with cords-and crawled under a table to get it. There he became stuck and was too weak to come out. Normally, Lankford says, he could’ve gotten out. She then put him in his walker. She says he didn’t want to walk; he was listless and wobbly. He dropped a juice bottle and tried to pick it up.

By this time it was past 3:30. Lankford took Eric out of his walker and laid him on the floor. He was crying, but not loud enough to wake Justin. Amanda and Chris were sitting on the floor in front of the TV watching “Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer.” Eric pulled himself up and stood leaning against some furniture. He slowly walked around the living room, supported by the furniture. Lankford saw him at the TV, trying to play with cords behind it, She was at the opposite side of the TV when she saw Eric’s feet go out from under him.

Lankford says she heard Eric’s head hit the linoleum tile floor with a “thunk.” She rounded the TV and saw Eric flat on his back. He let out a loud, lusty cry. Evelyn picked him up and held onto him while she walked him to calm him down. She covered him in a blanket and put him in his crib. Then she says she called Edwards at work. She told the mother that her baby had taken a hard fall and she should come take him to the doctor. Edwards said she was too busy. “I’ll call back later,” she said. It was now about 3:45.

Lankford went into the baby’s room. Eric was pale and convulsing, his arms and legs shaking violently. Lankford put Eric on her bed and tried to perform CPR, but the bed gave too much when she pushed down. She hurried Eric to the kitchen floor and resumed CPR. He regurgitated a small bit of carrot baby food onto Lankford’s dress. She called 911 twice and heard a recording. She was panicking. She tried CPR once more, then called 911 again. This time she listened to the recording. It said Balch Springs had no 911 system. By this time, Eric had stopped breathing. Medical testimony shows Eric was most likely already dead when the paramedics arrived and rushed him to the hospital.

Lankford called Roxie Edwards and told her they were at the hospital. She and the baby’s father arrived about the time Eric was pronounced dead. Jack Sheppard cried.

THAT’S THE STRANGEST NIGHT I’d had in a long, long time,” says the Rev. David Gibbs, pastor of the Cathedral of Life Full Gospel Church. It is months since the trial ended, and Gibbs, in blue jeans, white shirt and red suspenders, is sitting in one of the 24 pews in the tiny church. He is talking about the night of the murder. A night he spent with Lankford and Edwards.

After arriving home from the hospital, Lankford talked to church elders for counsel, including Rev. Gibbs and Rev. Tony McNeal. That same evening, Mary Edwards, Roxie Edwards’ mother, called Lankford and asked her to come over; there was an impromptu wake forming. Lankford, her husband and four church members went to Roxie Edwards’ and Jack Sheppard’s apartment on the mini-storage property.

All were struck by the eerie atmosphere. Roxie, Jack, Roxie’s parents and brother and a few other family members were there. Jack was openly grieving. It wasn’t long before Lankford was crying again. Edwards, who was serving drinks and playing music, and Edwards’ mother were consoling Lankford. “It’s OK, Evelyn, don’t cry,” they told her. Edwards was so calm that Lankford thought she was sedated. Witnesses say Edwards admitted that the baby had been in bad shape that day. “He was always pulling things on his head.” According to Lankford’s husband, one of the grandmothers’ boyfriends told Jack: “It was only a baby. You can have more.”

McNeal was taken aback by the family’s attitude. “We lost our baby when it was eight months due last year,” McNeal says. “Anybody who’s lost a child would be sad. No one was sad, except the husband.”

Two days later, the funeral was held, performed by Gibbs at the request of Roxie Edwards. Gibbs, who has performed scores of funeral services, says this one was unlike any other. He remembers it as “a little bit cold. It was weird. Jack and Roxie carried the coffin. Jack fell apart, and Roxie was holding him up. not crying at all.”

The couple went from the funeral back to their office to work. That afternoon, Carl Thrower walked in. Thrower had lived on-site and co-managed the property until being fired for getting into a fight with Jack. Thrower had been angered that co-managers had been assigned to his property, and besides, he couldn’t stand Jack. But he’d often seen Jack typing at the computer with his right hand while holding Eric in his left arm. He knew Jack loved Eric, he says, and he had come to pay his respects.

“Jack, is it true what 1 heard about Eric?”

Yes, Sheppard replied. He began to cry. Roxie Edwards “didn’t crack a tear,” Thrower says.

Then Sheppard spoke. “We think the babysitter killed the baby. We’ve always thought Evelyn was abusive.”

Thrower says he was immediately suspicious. He’d seen how Eric would often cry and scream when he was with Edwards.

The evening of the funeral Edwards and Sheppard left on a road trip through South Texas. They returned about a week later and immediately gave a barbecue, inviting Lankford, who went. But she didn’t know anybody there and felt uneasy. Why do they want me here? she asked herself.

In the next few months, Edwards continued to call her and tell Lankford of family arguments. So Lankford was surprised when Edwards quickly became pregnant, and was even more surprised when Edwards asked her to shop for maternity clothes with her. (The pregnancy later ended in a miscarriage.)

Lankford continued to dwell on Eric’s death, She says she couldn’t help but feel responsible after the baby died because he was in her care. And every time she thought she was over the baby’s death, something would remind her. “Like when Roxie asked one day why I hadn’t been to Eric’s grave,” Lankford says. “She said, ’Jack and I missed you there today. And Eric missed you.’ That blew me away for another 30 days.”

Still, Lankford’s emotional lows in no way prepared her for the shock and panic she felt when Roxie Edwards told her about the medical examiner’s ruling. She says Edwards consoled her, emphatically saying she didn’t think Evelyn hurt Eric. Still, within a few days, a Balch Springs officer told Lankford she would soon be arrested and charged with murder.

Now she asked herself, Why? Why do they suspect me?

THE EVENING OF ERIC’S DEATH, Balch Springs police took a statement from Lankford, who tried to surmise how the baby might have died. “Maybe he slipped,” she reportedly told Balch Springs investigator B.W. Smith (who agreed to talk to D Magazine, then refused to return phone calls). She was searching for an answer. She says she told the officer about the child’s history of bruises and sickness. She says she told him how the baby appeared bruised and groggy when he arrived. Lankford and her husband say they remember the officer replying, “It looks like child abuse.” Smith would later note that he felt Lankford was “telling the truth.”

On the report, Lankford’s hypothesis is noted as fact: Child slipped on some juice and hit his head. That this was Lankford’s explanation for the baby’s death, and not simply her guess as to what could possibly have happened, was from then on assumed by all involved.

All included Dr. Jeffrey Barnard, Dallas County’s chief medical examiner, who was charged with determining how baby Eric died. His opinion would dictate not only if the state filed charges, but more importantly whom the state would charge.

The autopsy was difficult. There were four bruised areas on the surface of the skull, the largest on the back of the head. There were no visible brain injuries. There were no other marks, cuts or bruises on the body. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome was ruled out. The body was tested for toxins; poisoning was ruled out. Then Barnard talked to the Balch Springs police department for investigative background. They told him the babysitter said the baby slipped and hit its head. Barnard then consulted with two other pathologists by phone, explaining what he saw. Although neither of them saw the body, each concurred: Eric was killed by blows to the head that were struck immediately before he died.

Barnard wrote his autopsy report:

“It is our opinion that Eric Sheppard. .. died as the result of a blunt force injury to the head. It is our further opinion that the mag-nitude of the force necessary to cause the concussive injury of the head rapidly enough such that the brain did not swell is inconsistent with the history that the deceased slipped on a linoleum tile floor and struck its head.”

Lankford’s supposition had taken on a damning life of its own. Now the child slipping and falling was considered a “history.1’ Since the medical evidence showed a standing fall could not have caused death, it therefore followed that the babysitter was lying. Lankford says she was just trying to guess how the baby might have collapsed. How much the investigative input colored the autopsy report is uncertain, but it is listed as one factor in the decision to label the manner of death “homicide.”

As soon as the medical examiner’s report was released, investigators sought out Edwards for an explanation. She told them Lankford had given her two stories about how the baby died: That the child slipped and fell, and that the child fell as he was reaching for his walker. Meanwhile, Edwards wanted a copy of the report-she had been bugging the medical examiner’s office for it-because her insurance company needed it. At about the same time. Lank-ford’s husband was told by a Balch Springs officer that she would be arrested for murder as soon as the paperwork was drawn up.

Evelyn Lankford began to search for lawyers. None would take her case because she didn’t have any money. Distraught, waiting to be arrested, she pondered her options that evening while thumbing through the TV listings. There she saw an advertisement for her legal savior, Catherine Shelton.

“I’M KNOWN AS A BITCH,”SHELTON I says from across an oak table in a conference room at her West End office. Shelton’s abrasive manner does frustrate judges and infuriate prosecutors. She’s been described as a lawyer only a client could love. “Of course,” she notes, “if I were a man, I’d simply be ’aggressive.’ ” Shelton has a reputation for doing anything to help her client. Judges say that’s because she harbors a righteous fuse that is easily lit if she believes her client has been wronged. And she believes that every day.

Lankford knew none of this when she called Shelton in August ’91. “I have very little money,” she told Shelton’s husband Clint, the office manager. He was intrigued enough to ask Lankford to come in and tell her story. “They all have their story, OK?” Catherine Shelton says. “But she didn’t have a story. She just came in and exploded, like a wet balloon.” Shelton took the case.

Lankford was arrested, and once Shelton arranged for her bond to be posted, she had Lankford come in and again relate what happened. Shelton had to determine a strategy. The most obvious was to contest homicide-argue that the baby died from a fall and create reasonable doubt in the jurors’ minds.

As she listened to Lankford, though, Shelton began to hear something else. She asked Lankford to write down all the times she remembered seeing Eric bruised or hurt in the nearly five months she cared for him. Lankford, sitting in Shelton’s office, wrote each item on a separate sheet of white paper, neatly, in script:

1. I was talking to Roxie on phone one Saturday and I heard Eric begin to scream. Roxie said he had fallen on a ceramic panther that stuck out from under an end table. On Monday morning when she brought Eric to me he had a large bruise on his cheek.

2. Roxie brought Eric to my house one morning. He had dark circles under his eyes and bruises on his cheeks. She said he Jell and hit the coffee table and it made Jack so mad he threw the coffee table outside. Several days later… I saw coffee table outside.

3. Roxie was at my house picking Eric up and she asked if I had seen Eric’s latest trick… She said if you give him a bottle he will fall straight back. Not try to catch himself or anything. She said the night before she gave him a bottle in kitchen and he just went straight back and struck his

head hard on kitchen floor.

She mentioned four other instances: Eric pulled a lamp on his head, pulled a hair dryer on his head, fell and hit his head on the fireplace, fell in a store and hurt himself. All resulted in bruises.

“That’s when it really began to hit me,” Lankford says. “You don’t want to believe it, but when you put it all down like that.. .”

Shelton was convinced. She would argue that yes, the baby had been murdered. She would argue it was Roxie Edwards who killed her own child.

For Shelton, that meant she had two objectives: prove a history of abuse and neglect; and disprove the only objective evidence- the medical examiner’s conclusion about when the blows had been struck. She called private investigator Mark White, a former police officer who agreed to investigate the case-including the parents. Then she asked a personal injury lawyer in her office, Garnett “Brit” Hendrix, to look at the autopsy report and find a way to punch holes in it.

The problem was in affording expert medical testimony. Shelton estimated she would need $3,000 to pay for a pathologist to testify. Lankford had already sold her furniture, her TV, everything, and still she would never be able to pay her legal fees in full. Shelton met with the church members to see if they could help.

That Sunday, shortly before the trial, Gibbs stood up and said they were going to pass the bucket once for Lankford. Every one of the 60 church members contributed. Some signed over their disability checks. In one pass, they raised $1,700. Gibbs said they could get the rest from the building fund. But, he said, the vote to do so had to be unanimous, since people had given that money for a new church. It was unanimous.

The case came to mean more to Shelton than simply defending Lankford, her “favorite client.” She easily gets worked up over perceived indignations that more jaded lawyers dismiss as the way things are done in Dallas. Because of that, she doesn’t respect-can’t stand, actually-most of the prosecutors who represent that system. This case was the perfect vehicle to vent her frustration with the district attorney’s office.

The prosecutor in the case, Erleigh Nor-ville, believed just as strongly that Lankford murdered a 9-month-old child, and came to detest Shelton and her assertions that Edwards had anything to do with the killing. Shelton’s snide remarks about Norville’s competence couldn’t have helped.

“The personalities in this case got in the way,” says the trial judge, Gary Stephens. “It complicated the trial.”

Partly because of this, the prosecution and defense couldn’t get anywhere near agreement on a possible pretrial deal. That is rare:Fewer than 3 percent of the people charged with a crime in Dallas County receive a jury trial. Most cases are plea bargained to keep the jail and courthouse doors revolving. But the plea bargain offered to Evelyn Lankford by the DA’s office was laughable to Shelton: 50 years, no probation.

Norville was convinced by the autopsy. There was no other evidence in the trial to suggest Lankford had a possible motive other than anger: no relevant criminal history (she had written a hot check for groceries more than a decade earlier); no weapon; no one who had so much as seen her angry. But to Norville, the medical report was enough. It could not be ignored; the state would be remiss not to file charges. The key unanswered question-could anyone else have done it?-might be cause for further investigation in TV dramas, but not in the real world and limited time of the DA’s office.

“There’s an inertia that occurs,” says criminal defense lawyer Stuart Parker, past president of the Dallas County Criminal Bar Association. “The various agencies assumed the babysitter was tying because of the ’history’ that the baby slipped on the floor. That gives them a suspect. It’s always easier when you have a suspect. You maximize things that help your theory, and you minimize things that hurt your case.” Once a suspect is identified, it’s not in the best interests of the office to continue a critical evaluation that may weaken the state’s case. The DA’s investigator often simply reinterviews the people the initial investigative agency-the police, the sheriff’s office, child protective services, etc.-has already talked to.

Catherine Shelton knew this. That’s why she had investigator Mark White talk to the same people the DA talked to, as well as everyone they could find who knew Lankford and Edwards. They found people who would attest to Lankford’s sweet, harmless nature and those who would testify to Edwards’ violent tendencies. And as the trial began, Shelton knew something the prosecution didn’t. She knew her goals-discrediting the medical evidence and the mother-rested strongly on the knowledge of two people: a surprise medical expert and Edwards’ brother, Gary Edwards.

A JURY TRIAL CAN BE EXPLAINED as a maze with two ways out-guilty and not guilty-where a mix of clues, experience and instinct leads the jurors toward their final exit. In these terms, the trial’s most important turn came once the 10-woman, one-man jury heard Roxie Edwards’ testimony.

“I just got a funny feeling,” says juror Jean Naczi. echoing sentiments of the other eight jury members who talked to D Magazine(one juror did not return phone calls, one declined to comment). “It struck me as really strange that I didn’t have a lot of sympathy for this woman who had just lost her child. I tried to feel warmth or sympathy or… I felt that if it had been anyone else sitting there testifying, I would have felt differently.”

Edwards came off as cold and defensive. She showed no emotion when she saw the autopsy photos or while talking about Eric. “I have four children and five grandchildren,” juror Linda Pace says. “When I talk about [mem], I light up like a Christmas tree. Not the mother, though.”

Lankford’s testimony only helped herself. Lankford cried, talked about Eric’s “little feet” and “droopy little eyes.” “She talked about him,” Pace noted, “the way a mother would talk about a baby-very tender.”

The only time anyone mentioned out loud that Lankford killed baby Eric was when prosecutor Erleigh Norville questioned the sitter.

“Were you surprised when Eric had seizures?” Norville asked.

“Yes, I was.”

“You were surprised because you didn’t hit him that hard,” Norville charged. “And you were surprised because you didn’t think you hit him against anything mat hard.”

“I never hurt that baby,” Lankford said quietly.

Courtroom wisdom says a jury doesn’t always know when it’s lied to, but it always knows when it hears the truth. Lankford’s statement, say jurors, rang true.

The lawyers had no idea what the jury believed, however. One courtroom observer, Aileen Linam, noted that the only time she saw a reaction from jury members was when Edwards admitted Eric had a history of bruises since he was 3 months old.

But Catherine Shelton felt the jury not only had to dislike Edwards, but had to think she could have beaten Eric before arriving at Lankford’s. The problem was that visiting Judge Stephens, who was given the case because he has a slow fuse, was tiring of Shelton’s attempts to try the mother. He continually removed the jury and conducted hearings of defense witnesses to determine if their testimony was relevant. (The jury spent more time out of the courtroom than in.) The second time Roxie Edwards was on the stand, Shelton was threatened with contempt of court and jail time if she wasn’t careful. He had grown weary of Shelton’s and Norville’s snide competitiveness, the obvious contempt each held for the other.

Shelton walked up to Edwards and held a check in front of her. “Recognize this?” she asked. Edwards said nothing. Shelton answered her own question. “It’s an insurance check for $20,000.”

Norville leaped up. She couldn’t believe the jury had heard that. “Everybody out,” said Stephens. The jury left.

Out of the jury’s presence, they discussed the insurance check. Shelton contended that there were actually two insurance policies, one for $5,000 and one for $20,000. She based this on what the child’s uncle, Gary Edwards, had told her. Edwards came forward with information about the alleged policies because of guilt over his family’s attitude. The night before the trial was scheduled to begin, Roxie Edwards had told Gary he was going to pay for helping the defense. Scared, he went to his grandmother’s house. There, according to Gary, Jack Sheppard pistol-whipped him severely.

Edwards maintained there was only one policy, for $5,000, that her mother had taken out for the baby. She said the $20,000 check made out to her was for double indemnity (which, if true, Shelton noted, was twice what she should have received). The jury heard none of this. (Also not explored was that the grandparents kept much of the money. On Oct. 3, they withdrew $5,200. On Oct. 11 and 15, while in Las Vegas, they withdrew another $1,500 of the money. Roxie and Jack withdrew $5,500 in cash at the same time, but it’s not known if they accompanied the grandparents.)

But Shelton had another, bigger surprise.

Erleigh Norville and the rest of the prosecution were shocked when Dr. Paul Prescott walked through the courtroom door.

MONTHS AFTER THE TRIAL WAS over, the district attorney’s office was still trying to discredit Prescott’s testimony. As Prescott noted, “It’s interesting that they’d say that since I’ve testified for the state on similar cases. Hundreds of times.”

Prescott, director of the REACH child abuse program at Chiildren’s Medical Center, had been approached by the defense team with the medical evidence. His finding: Because there was no brain swelling or damage, he would have ruled the cause of the baby’s death indeterminable. Shelton knew this could solidify the doubt she was trying to create in the jurors’ minds.

Prescott indeed impressed the jury, in demeanor and expertise. He said the blows could have been struck up to 12 hours earlier. He said that something else in the report- a mention that baby Eric had been treated for a condition where only one eye would dilate-could signify a history of child abuse. That helped to crystalize the doubts about Roxie Edwards in many jurors’ minds. The only testimony of significance left was that of Dr. Jeffrey Barnard.

The medical examiner was not impressive on the stand. He wasn’t as aggressive a witness as he usually is, and his explanation of why he thought the blow could not have been struck more than two hours before was not clear. His father was near death, and he resented being called away from the hospital. Besides, Brit Hendrix was particularly effective at only allowing Barnard to say what the defense wanted said. Barnard was asked if brain swelling-none of which was found in the autopsy-could take up to 12 hours to develop fully.

Well, yes.

That was it for the jury. The window of time-the only evidence against Lankford- had been widened to include time the baby spent with others. “I was surprised they didn’t stop it right there,” one juror said. Barnard would later note that there should have been some swelling if there had been many hours between the occurrence of the blows and the baby’s death.

In closing arguments, Shelton was uncharacteristically flustered and unsure. She was convinced she was right, but thought she would lose the case. Norville, however, was eloquent and moving. Her pleas for justice struck home.

After a few minutes of discussion in the jury room, a vote was taken to see if there was need for discussion. Nine said not guilty. Two said they weren’t prepared to vote yet. At about the 10-minute mark, one of the

two undecided agreed with the majority. The last holdout, Cheryl Nelson, the foreman, didn’t disagree, but she wanted to read the autopsy report again. She had once worked for Child Protective Services. Even though she thought she knew the person from CPS who investigated Evelyn’s own children before the trial and found no history or record of abuse, she wanted to be sure she wasn’t letting a killer go free.

The jurors groaned. “I’m sorry we didn’t go back in five minutes,” juror Johnnie Ryan says. “I wanted to make a statement that not only is she not guilty, but that this trial was ridiculous.” After about 45 minutes, and halfway through the autopsy report, Nelson relented.

Not guilty it was. When the verdict was read, Norville put her head down. (Roxie and Jack were last seen in the courthouse cafeteria, even though they were told a decision was about to be announced.) Lankford placed Bible verses she had been writing throughout the trial in Shelton’s purse.

The next day Shelton was treated for exhaustion in a hospital. And Lankford was free. “She always said she was a babe in Christ,” Gibbs says. “But after that I told her, Evelyn, you’re full grown.”

“IT’S A STORY UNENDED,” JUROR Pamela Kirkland says. The nine jurors who spoke are still frustrated. Frustrated because no one will be punished for the baby’s death. The only person who has suffered, they say, is Evelyn Lankford, the one who cared most for the baby.

Indeed, the trial wiped out the Lankfords’ already meager savings. Lankford now works two cleaning jobs, 18 hours a day, to make ends meet. Her husband Wesley collapsed outside the courtroom on the first day of the trial and has yet to recover fully. Still, Lankford is thankful for her freedom. She says God saw her through it, but wonders how many others there are like her who have been victimized by the legal process.

Lankford will get no apologies from the DA’s office. It says it put the right person on trial. Because of that, her attempts to get the charge expunged from her record will probably not succeed, as the prosecution would have to agree to help.

She says that despite everything, she’s OK now and trying to put it all behind her. “Good things came out of it,” she says. “I found my strength in God. Even though I had no control-people just came in and took control, and all I could do was fight for my life-I’m stronger for it.” But even as she says this, more than a year after Eric Shep-pard died, she again begins to cry.

Related Articles

Restaurant Openings and Closings

East Dallas’ All-Time Favorite Fries Are (Kinda, Almost) Back

Remember the fries from 20 Feet Seafood Joint? Of course you do. Boy, do we have some good news about a new place called Goldie’s.

Local News

Leading Off (4/16/24)

Cloudy today, with a high of 88 and chances legal proceedings

By Tim Rogers

Nightlife

Flavor Leads With A Flourish at Margaret’s

Located inside JW Marriott Dallas Arts District, Margaret’s offers an Escape From the Ordinary