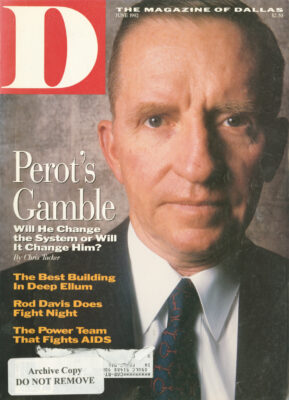

Ed. Note: This story originally ran in the June 1992 edition of D Magazine. Following his death from leukemia at the age of 89, we are republishing it.

H. Ross Perot, it seems obvious, spends a good deal of time in the barbershop. His no-nonsense Navy-issue ’do, favored by fighting men from Sgt. York to Audie Murphy to Bull Simons, requires regular tending. So it was that one day in 1962, the 31-year-old IBM salesman was awaiting a trim and browsing through Reader’s Digest when he came upon a pregnant quote: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.”

Perot says the quote inspired him to change his life, giving him the strength to strike out on his own and, six months later, form Electronic Data Systems, the computer company that was the fountainhead of his billions and the mother lode of his personal and corporate mythology.

Viewed with 30 years’ hindsight, the tableau is quintessentially American: Henry Ross Perot, the uncommon common man who would become one of our country’s legendary entrepreneurs, sits in a humble barbershop and hears a challenge in the words of Henry David Thoreau, perhaps the most American of philosophers. Note that Perot is not reading Playboy or The New Yorker, but Reader’s Digest, the bible of Middle America. Norman Rockwell, one of Perot’s favorite artists, might have titled the scene Moment of Inspiration.

It’s the stuff of myth, a tale that will be told to millions of Americans if Ross Perot goes through with his almost-promise, almost-threat to run for president. If his crusade leads him to the White House, that story and other bits of Peroviana will take their place in the American treasury of great-man lore, along with Lincoln’s reading by firelight and Washington’s full disclosure about the cherry tree.

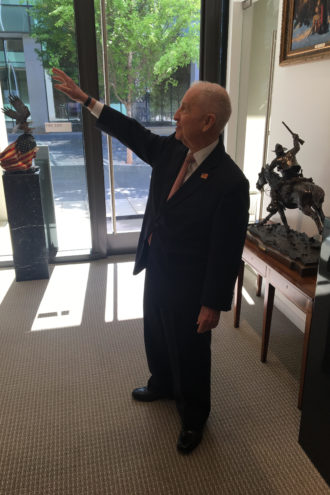

Did the story happen that way-really? Perot says it did. To this day he’s got the Reader’s Digest page with the Thoreau quote framed in his office, along with one of the five original paintings of The Spirit of 76, some Rockwell originals, some muscular Remington bronzes and numerous eagles, Perot’s spirit animal. The Quote is part of an impressive shrine to rock-ribbed American virtue-patriotism, sacrifice, love of family, small-town innocence.

Assume that it happened that way. If it didn’t, it should have. So, once upon a time in the early ’60s, Ross Perot (no H. back then) was leading his own life of quiet desperation. He was unhappy selling computers for IBM in Dallas. Not that he wasn’t good enough for IBM. Problem was, he was too good. IBM was old, huge, and arthritic. The Texarkana-born Perot was young and driven. He had his own ideas and an appetite for change. IBM had procedures and protocols and quotas.

During his fifth year with IBM, 1962, Ross Perot had made his yearly quota by Jan. 19. Technically, he was finished for the year; the company required nothing more of him for the next 346 days. At 5-foot-7-inches, he was bumping his head against IBM’s ceiling. Already, the bureaucracy was fencing him in.

So Perot quit, and on June 27, 1962, his 32nd birthday, he started Electronic Data Systems. Six years later he took EDS public and found himself a multimillionaire. No more quiet desperation for Ross Perot.

Now, 30 years later, from the mountains to the ocean, from the board rooms to the barbershops, many of Ross Perot’s fellow citizens are living lives of increasingly loud desperation, sick to death of public servants who live like masters and a political system that many believe has ceased to function. From the Babel of the talk shows come strident, angry voices. They would raise up a champion to smite the enemy.

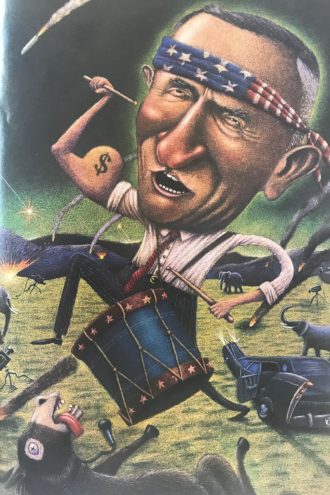

In this late spring of our discontent, Perot has eclipsed Jerry Brown and Pat Buchanan as the supreme protest candidate. Whether he will melt in the summer heat or be roasted by partisan flame throwers remains to be seen. He may yet, as he did in 1988, walk up to the edge of the race and back away. If he runs, he may find himself hamstrung like Gulliver by media Lilliputians scurrying after some decades-old remark or tax return.

If Perot runs and wins the election, America will have consented to a new revolution. If he loses, as he almost certainly will, he still might bring some dignity and common sense to what is now a degrading, infantile ritual of character assassination. Or, driven by anger and ego, he might use his vast wealth and combative style to pursue a scorched-earth policy against George Bush, making the race a three-way demolition derby. Ironically, the nasty result could alienate even more voters.

As of May, things looked rosy for Perot. Polls around the country showed him taking 20 to 32 percent of the vote from George Bush and Bill Clinton, a terrific start for a man who has never sought a vote in his life. In Texas, things looked even better: One statewide poll showed him leading adopted-Texan Bush by five points, with Clinton a distant third.

The party pros say those numbers will shrink, not grow, once voters “get to know” Perot. They may be right, but you don’t have to be Perot’s biggest fan to hear something sad and sick in those confident dismissals. Translation: Once the attack ads strip him bare, once the negative research boys reveal his evil twin, Perot is finished. The handlers and spin doctors have turned politics into a walk through a dark alley filled with liars, muggers and con men. To make it down that alley, you’ve got to have better liars, muggers and con men on your side. To the insiders, Perot looks like Little Red Riding Hood on his way to Grandma’s. Easy pickings.

But maybe not.

Perot has formidable strengths—his staggering wealth and willingness to spend it on a cause; his image as a straight-shooting populist; his legendary business success; his impassioned followers; his uncalculating love of country; his bullish confidence. To beat him, of course, the two parties will work to turn these strengths into defects. Michael Dukakis felt great about his ACLU membership until Lee Atwater got hold of it. The sleaze miners are already spelunking in Perot’s past, and they will try to trash him with whatever they can find. In the next few months, Perot will enter the dangerous game of image politics, trying to sell himself to millions who now know him only as a sound bite. He will, in effect, be creating himself for the country, while his enemies strive to create a Perot repellent to voters. Which Perot will voters believe is the real one?

The last man to gain the presidency without previous political experience was Dwight D. Eisenhower, another native Texan and a bona fide war hero. Perot has never held office, but he is no stranger to the political wars. He can boast that two governors, Republican Bill Clements Jr. (1979) and Democrat Mark White (1983), called on him to lead statewide crusades aimed at stopping drug abuse and improving the state’s woeful education system.

Perot’s most moonstruck fan cannot argue that he rid the state of drugs, though his lobbying efforts as chairman of the Texas War on Drugs did make the state less hospitable to drug dealers by, among other things, expanding police wiretapping powers. In the case of education, Perot’s controversial “no-pass, no play” rule stands, much to the chagrin of many high-school athletes. Some of the other reforms have fared worse. Convinced that the elected state board of education was controlled by special interests, Perot proposed that the board be appointed by the governor, who would choose its members from qualified candidates proposed by legislative leaders. It was political heresy. Perot was saying that the popular vote is not always the best way to achieve the public good; “the people” don’t always know what is best for them. In this case, the people disagreed; after two years of the reform board, Texans voted in 1987 to go back to electing the board.

His crusades earned Perot lasting enemies. Civil libertarians said his drug-fighting proposals trampled on the Bill of Rights, a charge that gained new life when he reportedly told some Dallas journalists that South Dallas neighborhoods should be cordoned off and swept for drugs. (Perot denies making the statement.) And many a Texas teacher still seethes over the infamous competency tests designed to purge their ranks of mediocrities. Angry teachers couldn’t vote against Citizen Perot, but they took their bile out on Mark White, helping to defeat him in 1986.

While his efforts did not rid the state of drugs or illiteracy, Perot enjoys a residue of gratitude from many Texans, both Democrats and Republicans. Unlike Clayton Williams, another wealthy Texan who tried politics, Perot can argue that he’s been down in the trenches working on two of the country’s most nettlesome problems. And the passage of time makes Perot the Reformer look prescient. We’ve got kids killing each other for crack, he’ll say. Our schools are the joke of the planet. I tried to help.

Perot may have a harder time putting a positive gloss on his campaign to weaken the Dallas Citizens Police Review Board, a move that earned him the scorn of local liberals and progressives. Working in league with the Dallas Police Association, Perot and his lawyer/ advisor Tom Luce met behind closed doors with Mayor Annette Strauss and other council members—excluding key minority leaders Diane Ragsdale and Al Lipscomb—and watered down the proposed reforms. Among other things, Perot and his police allies objected to the board having the power to subpoena officers and potential witnesses. In the referendum that followed, 74 percent of Dallas voters sided with Perot, turning the review board into a toothless tiger. Perot is sure to be, in his phrase, “sound bitten” on the review board issue. Imagine the Democrats’ attack ad:

Announcer speaks as we see Los Angeles cops beating Rodney King:

Ross Perot. He’s the Texas billionaire who says the people should take back their government. But when Dallas minorities wanted protection from police brutality, Perot said no. Billionaires can hire their own security guards. Who’s going to protect the rest of us?

As for experience in foreign affairs, Perot starts with stronger credentials than the typical challenger, having been at least a bit player on the world stage. A Naval Academy graduate who never saw combat in his four years of service, Perot can’t match Bush’s glittering wartime record, but he may not have to: The public already has a sense that Perot would not start from scratch as commander in chief.

Perot won a measure of fame and the undying loyalty of many in the military with his Christmas 1969 mission to Vietnam. At the request of President Richard Nixon, Perot chartered two airliners and attempted to ferry supplies and mail to American POWs in North Vietnam. Perot’s planes, with reporters on board, were refused entrance, but he emerged as a superpatriot acting to help those who had sacrificed for America.

Perot later served on Reagan’s Foreign Intelligence Advisor Board, a citizen group charged with reviewing intelligence issues. Reportedly, he resigned in anger over the issue of Soviet spying at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. Perot wanted to replace all the Soviet workers in the embassy with Americans, and offered to pay the cost out of his own pocket. When little action was taken, he quit.

Perot’s trump card in foreign affairs is obvious: He’s the only candidate in the race who’s been immortalized in a best-selling adventure story and a successful made-for-TV movie. Ken Follet’s On Wings of Eagles, the Perot-authorized story of the 1978 rescue of two EDS executives from an Iranian prison, burnished Perot’s image as a strong, decisive leader reaching halfway around the world to right a wrong. The State Department experts and the CIA honchos were powerless to help—but not Perot. Sources in the Middle East disputed some of the details of the rescue mission, questioning whether Perot’s strike force, led by Col. Arthur “Bull” Simons, really incited the riot that led to the prison break But the quibbling never caught up with the main story, which Perot sees as another example of “ordinary Americans doing extraordinary things.”

Taken together, such incidents give Perot a solidity on foreign affairs that many a presidential candidate—including Ronald Reagan in 1980—has lacked. Long before the first Perot petition was signed, reporters were treating Perot like a retired military commander or diplomat, seeking his opinions on all manner of foreign problems and crises. When the U.S launched an air strike against Libya in 1986, France refused to allow American fighters taking off from England to overfly French territory. Government officials muttered through back channels, but Perot said what was on many minds: “My strongest feelings are about the French. We saved their nation twice in this century. I would like for every French leader to go to Normandy, where the American fighting men who fought for France are buried, and examine their consciences. If we ever start to consider spilling a drop of American blood for the French, I’ll use every resource to see that we don’t.”

In the movie version of Eagles, Burt Lancaster, playing Bull Simons, explains his loss of faith in the system: “I was looking for statesmen, and all I found was politicians.” This summer and fall, voters will be encouraged to see Perot as that missing statesman.

No candidate today escapes a thorough crotch-sniffing by the media’s character beagles, and Perot will be no different. Ironically, he may be the only recent candidate who has been criticized for being too straight. Stories about the early days of EDS, many of them apocryphal, stress Perot’s strict discipline. The company code included drug testing, a decided preference for short hair and close shaves for men, and swift punishment for anyone guilty of what is today called sexual harassment.

Power may be the ultimate aphrodisiac, but Perot is notoriously devoted to Margot, his wife of 36 years. Just as important, Perot, unlike the frisky Gary Hart and Bill Clinton, seems convincing as a happily monogamous square. As for drugs, the media snoophound who can turn up illicit herbs and powders in Ross Perot’s background can probably find that locked Parkland Hospital ward where they’ve been keeping the comatose Jack Kennedy all these years.

But the character test goes beyond wine, women, and bongs. What about Perot’s “Roger and Me” stories? In the cut-and-thrust of the campaign, Perot is sure to be asked about contradictory accounts of his years as self-appointed gadfly to Roger Smith, head of General Motors. In 1984, Perot sold EDS to GM in exchange for $2.5 billion and a seat on the auto giant’s board of directors. Perot says that over the next two years he suggested numerous improvements and reforms to Smith and other GM brass, but was steadfastly ignored on matters great and small.

For instance, in a 1988 Fortune article, “How I Would Turn Around GM,” Perot waxed on about the ponderous GM bureaucracy and told of meeting with the 20 leading Cadillac dealers, all of them “mad as hornets,” in Dallas. Perot heard their beefs, promised them action, then asked why they hadn’t put their complaints on their annual surveys.

As Perot recalls it, an older man stood up and said, “Ross, I’ve been a Cadillac dealer for 35 years and this is the first time anybody has ever given us an opportunity to tell them what is wrong.”

“What about the surveys?” Perot asked.

“There are no surveys,” the man told him.

In rebuttal, Roger Smith said that he’d “never met a bashful dealer” and insisted that such gripe sessions were routine in the company, as were annual surveys. Likewise with Perot’s statement that he, Perot, gave personal replies to “every customer complaint” during his time on the board, while GM drones merely sent out form letters. Not so, wrote Smith. As for Perot’s claim that he lobbied to get rid of the “25th floor”—the posh teak-lined board room—of the GM building in New York, Smith was blunt: “Ross Perot never suggested that to me or anyone else I know.”

Such discrepancies prove nothing in themselves, of course. Smith’s image took a pounding in the best-selling exposé Irreconcilable Differences, so Perot may look forward to seeing his spat with Smith replayed over the next few months. Besides, the popular perception has gelled on Perot’s Motown adventure. When GM bought him out for $700 million in 1986, the payoff was widely seen as “hush money” paid by lazy tycoons who couldn’t stand Perot’s criticisms any longer. GM’s continued loss of market share, coupled with layoffs and plant closings, makes Perot look prophetic.

More “character” trouble for Perot may come from the 800-pound gorilla file-incidents in which his feisty temperament betrayed his judgment. In 1987, Dallas police stopped Perot’s daughter-in-law for speeding. An officer noticed a handgun in her car, a violation of state law. After some discussion, the cops decided to let her go with no charges. Perot then summoned the two officers to his office—not to thank them for giving Sarah Perot a break, but to berate them for being rude to her. Will Perot face a law ’n’ order attack from Republicans?

Announcer speaks while we watch cops play with children, endure crowd abuse, attend funeral of fallen comrade.

Ross Perot. He says he’s on the side of our police officers. But when Dallas police caught his daughter-in-law with an illegal firearm, he insulted the officers and screamed at them-even though they were just trying to do their job. George Bush believes in equal justice for everyone. If you do the crime, you do the time. That’s the American way. (Shot of Bush being applauded by hall filled with cops.)

In mid-April, Perot got a foretaste of the fall campaign when Newsweek, NBC News and dozens of newspapers declared themselves shocked—shocked!—that Perot, a lifelong basher of Big Government, had in fact made millions from Uncle Sam. The stories are true if not new: EDS fattened, in the early years, by picking up state contracts to administer Medicaid and Medicare programs. As long ago as 1971, the left-wing journal Ramparts dubbed Perot “America’s First Welfare Billionaire.”

The Daddy Welfarebucks story carries a nugget of irony, though Perot denies any inconsistency or hypocrisy. He has never been against government, he says, only against government waste. And nobody in the Social Security Administration argues that EDS didn’t do a good job, even though Perot squabbled with the bureaucracy over government demands to audit his books.

Exasperated, Perot recently said that “if facts matter, EDS saved the Medicare system. We took one contractor after another that was failing. We saved the government hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Perot’s Alliance Airport project in Fort Worth could be a pricklier problem. Aided by former House Speaker Jim Wright (the very model, to many, of a tainted old-time pol) and millions of taxpayer bucks, Perot and his son, Ross Jr., built a private, commercial airport that is a veritable money machine. Critics say they’ve run roughshod over local school districts and municipalities, taking land off their tax rolls and costing them precious dollars. Now, the Perots want the government to pony up another $120 million to extend the main runway, an idea that had drawn fire from some local critics long before Perot issued his 50-state dare. As Republican snipers stepped up the fire, the Federal Aviation Administration delayed the extension.

Perot says the FAA decision didn’t hurt him, “but it hurt a lot of people out there. The Republicans boasted for three weeks that they’d hang Alliance around my neck, and they did it. Now the whole area is furious at the Republicans.”

Whether Alliance hurts or helps Candidate Perot outside of North Texas depends, like everything in a campaign, on whose version of the facts voters accept. The Republican sniping over the airport is part of an overall drive to tarnish Perot’s image as a self-made, two-fisted entrepreneur, while Democrats are bound to use Alliance as another example of the rich getting richer. Perot, for his part, will defend Alliance as one more example of his forte—”creating taxpayers”—and tie the airport deal to one of his main themes, making America competitive again: If the U.S. Commerce Department approves, the Alliance area will be designated the largest foreign-trade zone in the country. Perot will parry the “boondoggle” charges by reminding voters that FAA officials-who are, after all, part of George Bush’s team-stand behind the project and will certify that Alliance is in the public interest.

Perot scorns the “Republican dirty tricksters” he believes are behind the welfare-king and Alliance stories. He soundbites back: “It’s beyond amateurish. I wonder if they have anything positive they stand for. Hitler’s propaganda minister, Goebbels, would revel in this.”

Perot’s positions on the complex problems that face the country are, to be generous, evolving.

Beyond repeated claims that he’ll use the “electronic town hall” of television to rally public support, he’s been light on specifics. He’s sort of for some kind of gun control (as long as the NRA and cops and judges can agree on it). He believes women should have the right to choose abortion but wants much more stress on personal responsibility and hasn’t spent “10 minutes” thinking about federal funding for abortion, same-sex marriages, and myriad other hot-button issues presidents are supposed to talk about. A “strong family unit” would “wipe out most of our problems,” he says, but he doesn’t list the government policies, if any, that strengthen families. On foreign policy, he laments America’s habit of creating “Third World bad boys” (Noriega, Hussein, et al.) who turn around and bite us.

As part of the “world class campaign” he promises, Perot says he’ll develop positions on most major issues. His main focus, though, is getting the engines of the economy roaring again. Ask him how to revive flagging industries or cut the federal deficit, and his eyes glint like George Bush’s used to when the topic was foreign affairs. This is business talk. He’s home.

Still, most of Perotnomics is hardly revolutionary. He’s not hostile to higher taxes for the rich, though he’s slow to define “rich.” The existing tax system, he said on the “Donahue” show, “is like an old inner tube with 100 patches and every new patch is put on by a special interest.”

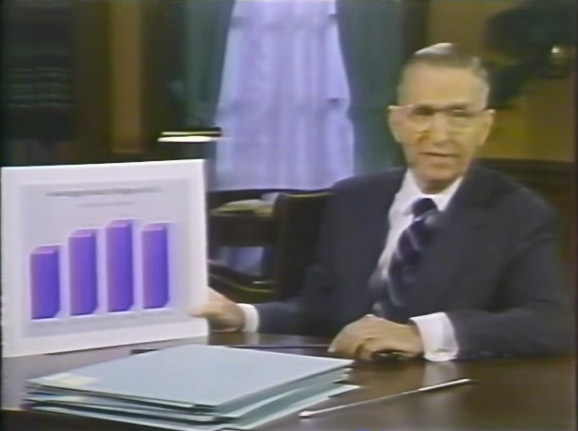

Chatting on the KERA program “Between the Lines,” he said he’d wipe out the federal deficit by, among other things, making Germany and Japan pay for their own defense (a sensible if unoriginal idea), giving the IRS better computers to improve collection efforts (an idea that backfired on Dukakis), and of course cracking down on that bête noire of Republicans, waste and abuse. Panelists pushed him for specific budget cuts, but when he was asked to explain a previous statement about means-testing for Social Security recipients—a political hot potato—Perot got angry and spent precious time dressing down the questioner. The ensuing snit proved once again that nobody puts words in Ross Perot’s mouth, but the audience learned nothing about his ideas on reforming Social Security.

The most sweeping change that can be inferred from Perot’s sketchy statements involves a much closer cooperation between business and government. We’ll solve our problems “industry by industry and company by company.” says Perot, promising a whirlwind start.

He’d have a “rough-cut plan” within 90 days of his inauguration, first for the automobile industry, then for others. Here, Perot sounds like any pipe-dreaming luncheon speaker, lapsing into sports metaphors as he waxes on about forging employees and management and government into one cohesive “team” dedicated to one goal: making the best products in the world. Asked to elaborate, he says he hasn’t had time to develop specific positions on “everything from frogs to mosquitos.” He makes it clear that in his view, Washington lacks not economic theories but the political courage to do what’s right.

Perot’s nascent ideas about the ailing economy and bloated federal budget are based on sentiment and morality, not Laffer curves and B-school theories. He believes, along with some conservatives and liberals alike, that in the 1980s America broke the basic social contract between generations. In typical fashion, he explains our failure through one of his beloved Norman Rockwell paintings, “Breaking Home Ties.” The canvas depicts a father and son waiting for the train that will take the boy off to college, expanding his horizons beyond those of his parents.

“That’s the story of my life in that painting,” Perot says. “My father was a very smart man, but he was forced to drop out of school at 14 to become a cowboy. My parents’ dream was for me and my sister to go to college.” Perot believes that too many Americans today, along with their government, have lost the will to work for the next generation-hence our $4 trillion of debt.

“Our parents worked and sacrificed so we could have better lives,” he says. “We’ve spent our children’s money.”

Of course, any successful candidate is much more than the sum of his programs. After eight years of Ronald Reagan and four of George Bush, it’s clear that voters don’t demand a president who can cite chapter and verse on economic theory, the problems of the inner cities and so on. Reagan didn’t stay up late reading Milton Friedman and Arthur Laffer, but he won two landslides despite critics who said he was just a doddering figurehead. In fact, opinion polls repeatedly showed that while majorities disagreed with some of Reagan’s policies, they continued to trust and respect him.

So it will be if Perot catches on with America. If voters like and trust a candidate, they will forgive him an imperfect grasp of matters that bore most people anyway. If they don’t like and trust him, an encyclopedic knowledge of the issues may not pull him through, as Bill Clinton seems to be finding out. This fact about the electorate drives political junkies and intellectuals up the wall, but it’s still a fact.

At first glance, Perot looks like the ultimate square peg in the round hole of politics. He’s testy, impatient, arrogant. He doesn’t suffer fools gladly-and he meets a lot of fools. He has said repeatedly that anyone intelligent enough to do the job of president wouldn’t want it in the first place. He seems temperamentally unsuited to the madness of the campaign circus.

“I hate talking about myself,” he told an interviewer recently. “I will not stand here and say, look at me, here are all the wonderful things I’ve done. What I did for the poor, for minorities, the homeless.” That does away with 95 percent of all political rhetoric. But there’s more: Describing how he’d approach problems as president, Perot says he favors “taking things to pieces, analyzing them, looking at the options, taking three or four pilot programs, explaining this to the American people and really making something work. See, I’m an engineer. I have to think logically, step by step.”

Thinking logically, step by step, while minicam reporters swarm for sound bites is no easy task. “There’s no way to finish anything without being interrupted,” Perot complained recently-and that was during relatively mild questioning on a local TV program.

A key question for Perot is how the public will react to his famous prickliness with the press. He could come off as mean and evasive, or he could benefit from a growing sense that arrogant mediameisters have taken their role as the people’s tribunes farther than the people want them to go. Remember how George Bush’s dust-up with Dan Rather rebounded to Bush’s credit.

Perot’s campaign might end with him being shouted down by the Rev. Al Sharpton while trying to visit a thriving Korean grocery store in the South Bronx. But all of this presumes that Perot will run a conventional campaign, making himself into another hungry chameleon who will, in Bush’s telling phrase, do “whatever it takes” to get elected. What if-just what if-Perot refuses to do “whatever it takes”? And what if people find they like it that way?

Our political candidates today spend as much time explaining away perceived sins as they do discussing their programs. With the media pack baying in pursuit, the treed candidate grimly concedes that a greens fee receipt from 1977 proves that he once played golf at a country club that at the time excluded Lithuanians. But he insists that his score for the round, an atrocious 17 over par, shows that he was “deeply distracted” by the ethical questions involved. However, one of the candidate’s golfing partners recalls him as “gleeful” over a rare birdie that day. In other news…

This idiotic process stems from a Faustian bargain we’ve made with our candidates. They’re all Pander Bears. They will wear yarmulkes and eat tacos while marching in the St. Patrick’s Day parade. They will say yes to everything we want and its opposite. They have become prostitutes in the truest sense of the word, willing to suffer any indignity, swallow any abuse so long as they get to wake up in the White House next January. The only way they get any business is by bad-mouthing their rivals on the other comers. Of course, nobody respects them in the morning. We know in our hearts that no person of dignity and substance would live this way.

Perot likes to quote his hero, Winston Churchill: “Never give up. Never, never, never give up.” But Perot may be unable to resist the forces that work to trivialize every candidate. He’s already traded quips with David Letterman; by midsummer, he may turn up on Oprah’s show between transvestite bricklayers and the author of The Vegetarian Amputee’s Guide to Great Sex.

In the early going, though, Perot seems to be charting a different course thanks to the very different bargain he’s made with his supporters. He’s saying, in effect, “I don’t want this job. I don’t need the hassle and I sure don’t need the money. But we’ve got serious problems and I’ll help if you say so.”

If he can stay that course, Perot could help change the whore-and-john relationship between candidate and public. He skipped the party primaries and is holding his own primaries by petition. His megawealth means he won’t have to waste time schmoozing with celebs at Hollywood fundraisers and won’t have to worry about offending powerful contributors. Don’t expect to see him stumping in sombreros, union jackets or college letter sweaters.

Whether he planned it or not, Perot’s New Deal with his supporters allows him more control over the agenda. He can have it both ways. Not my will, but thine, he says. I’m not flying into this fray on wings of ego, I’m doing it for you. But his no-strings arrangement means he can also say: This far and no farther. I’m not for sale-even to those who support me. I will not be chopped into media chow.

Time and again, Perot says he’s coming to talk about painful facts and he’s not bringing any Novocain. He says he won’t be the candidate of illusion. He wants to tell the hard truths and tackle the intractable problems symbolized by that $400 billion deficit. Perot says he’ll continue to tell people to “look in the mirror” to see who to blame for our problems-and who can solve them. If that’s not what people want, he’s fond of saying, “you’ve got the wrong guy.” There may be a bumper sticker—or a hit record—in that.

I had a strange dream the other night. It was twilight, and I was standing at the edge of a cliff. Ross Perot was urging me to jump. “Now you ask who’s going to catch you,” he said. “Don’t worry. We’ve got it figured out.” Then I felt something around my ankle. A bungee cord! Good ol’ Ross! But then I saw that the snaking cord was tied only to him. As I jumped, strangely unworried, he was saying something about leadership.

Voting for anyone, whether a lifelong politician or a brash outsider, requires a leap of faith. All of us who make up the voting minority will leap for someone this fall. The scary thing is this: The person we will vote for does not exist right now; he is being created. Remember, in the spring of 1988 George Bush was a dithering wimp and Michael Dukakis a brainy immigrant’s son who embodied the American dream. By Election Day, Dukakis had been changed, werewolf-like, into an effete East Coast geekoid, barely American at all, admitting on TV that he wouldn’t even execute a creep who raped and killed his wife. Bush, by contrast, rocketed across our screens in a macho cigarette boat, swollen with pork rinds and testosterone, a flag-waving fire breather pledging allegiance to keeping Willie Horton in the slammer.

We’ve all seen this happen before. But this time, it’s someone we know who’s being melted down and recast in the campaign crucible.

When Newsweek sneers that “nobody can recall a would-be presidential candidate who asked his country to do so much for him, up front, before he does anything at all for his country,” we know that they’re wrong. Perot might be a disaster as president, but it’s simply incorrect to say he has given nothing of his time, fortune and devotion to America. Here at home, Perot doesn’t rank as our leading philanthropist, but his gifts to the Boy Scouts, the Dallas Independent School District, the Meyerson, and the Arboretum are stubborn facts of life in Dallas.

We know him, and we know the warts aren’t all.

Will Dallasites recognize Perot in six months? Can he go through the coming storm and remain our local billionaire? Or will he end up as a lame joke in a Jay Leno monologue, a footnote to another meaningless campaign of symbols without substance? I don’t know that I’d vote for Perot, but it would be sad to see him Dukakisized. His accomplishments, his mistakes, his ego, his confidence are ours too, in a way. Can all that vanish in a 60-second attack ad?

If he runs a serious campaign, Perot deserves better, and so do the voters. A replay of ’88, with Perot as Dukakis and Alliance Airport as Boston Harbor, will do nothing to reduce a $400 billion deficit, revitalize American industry or salvage the underclass. Perot’s real task—a tall order for anyone—is to run a campaign that actually means something real, posing tough questions to voters presumed to have brains.

“I want to shock the system so that people will talk issues,” he says. Let’s hope he can do it. Otherwise the 1992 presidential election could boil down to Hillary Clinton, the New Woman who will not bake cookies, vs. First Grandmother Bar Bush with her twinkly warmth and gutsy stand against facelifts. (She’s so real!) While Bill Clinton blows sax on the talk shows, George Bush will drive an 18-wheeler to a flag factory.

Perot says he finds such stunts “repugnant.” So do millions of his fellow Americans. That’s why, if he runs an honest race and talks to us like thinking adults, he will make his most important contribution yet to the country he loves. Then he can return to semiprivate life on November 4, having been spared the nightmare of dealing with Congress. Imagine a presidential campaign that left a good smell in its wake. If Ross Perot can pull it off, we all win, even if he loses.

THE BOSS ON ROSS

American Airlines’ Robert Crandall has signed a Perot petition, but when we asked other Dallas business titans for their opinions, we got no-comments from William Howell (JC Penney), Jerry Junkins (Texas Instruments) and the usually talkative Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines). Lester Alberthal, now head of EDS, said through a spokesman that he would say nothing about Perot or any other candidate. Robert Decherd of the A.H. Belo Corp., owner of The Dallas Morning News, said his editorial page would do his talking. A few CEOs, however, shared their thoughts on Perot:

CHARLES TERRELL, Unimark General Agency: “He’s a super person at the right time. I think it would be great for Dallas. I couldn’t be more enthusiastic. I would’ve signed his petition if I hadn’t already voted in the primary. It’s a viable candidacy, because now is the time for an independent candidate, and we’ve never had an independent so secure financially. And Ross can hold his own with anybody. He certainly can build coalitions.”

BILL SOLOMON, Austin Industries: “I supported George Bush for a long time and have worked on his campaigns going back to when he ran against Lloyd Bentsen for the Senate [1970], and I have not decided at this time to do otherwise. However, I also greatly admire Ross Perot and am fascinated by his candidacy and the historical significance it could have.”

JESS HAY, Lomas Mortgage USA: “He’s been an outstanding public citizen in my view. His decision to run, if he makes it, would not be out of character for the kind of commitment to public service that he’s made in the past. I’m a Democrat, and I believe that the best agent of change would be [Bill Clinton]. But I say that without demeaning in any way the character of Ross Perot as a potential leader.”

REECE OVERCASH, The Associates:“I think it’s a greatidea. I think it will be good for Dallas, good for government. It will be the most exciting campaign since Truman-Dewey in 1948. He’s a no-nonsense, common-sense kind of guy who says it how it is, and people want that.”