The last thing Patricia Go forth. or her doctors, thought she had was TB. A middle-class woman from Irving, she didn’t fit any of the high-risk categories: homeless, elderly, foreign-bom, poor, minority, HIV positive. She didn’t even have the age-old symptoms- hacking or bloody cough, chronic tiredness. Just turned 50, remarried and anxious for a new start in life, she seemed like the rest of us -immune to and ignorant of a disease that, while still one of the lop killers in the world, hasn’t held that claim in America since the turn of the century. But she had a spot in her right lung. It took five biopsies and a CAT scan before a series of doctors finally discovered, or accepted, the truth about what the spot was. At the time, Patricia was grateful. “When you think you have cancer, you think-thank God. it’s TB,” she sighed. She had a point, though it was not so comforting as she might have wished. You can certainly live through TB-there’s a 90 percent chance of recovery if you get treatment. Another way of saying that, however, is that you have a one in 10 chance of dying. If you are HIV positive, or have AIDS-both closely linked to the new TB epidemic-or if you develop one of the new. highly lethal, mutant strains, your chances of beating TB could fall even lower, from about 50 percent, the same as if you had no treatment at all, down to nearly zero. So, as Patricia Go forth would leam, her thanks were to be tempered.

Like most of us, she had been too sheltered from the reality of a supposedly conquered disease to know why it was commonly known as “consumption.” Though not as baffling to cure or dramatically deadly as AIDS or cancer, TB is often just as draining. And in some ways it is considerably more alarming. The disease may not reclaim its old pre-World War II terror, when entire families were shredded and sanitariums were halfway houses to the morgue, but few officials thought AIDS would fan out so fast, either.

In fact, a TB catastrophe by the end of this century is an all too real possibility. The resurgence is already classified as an epidemic. Spread by hardy airborne bacteria, TB is very, very contagious. And though it incubates in “seedbeds” of poverty and social disarray, it is no respecter of persons, boundaries or strata. It calls forth no facile judgments of morality or lifestyle. It invades us neither via semen, blood or toxins, nor by touch or taste. It arrives by simple intake of breath.

Most of the time, thanks to the ability of the hardy TB bacillus to remain dormant for years and for the active, contagious form of the disease to mimic common ailments like colds or flu, we don’t even know where we got it. Patricia Go forth never found out. Neither did her husband, Charles, a 53-year-old insurance broker who skin-tested positive for the disease at about the same time his wife’s diagnosis was confirmed by X-ray. Whether Patricia infected Charles or vice versa doesn’t matter. Either could have picked it up anywhere.

As soon as she began the yearlong treatment at the county health department’s TB elimination and control division, Patricia teamed that, as with cancer, even getting well can be hell. In Charlie’s case, the suffering took the usual form-nausea, sluggishness, depression, isolation. And he only had to take the simple daily pill, a primary anti-TB drug known as INH (isoni-azid). Actually, he generally felt pretty bad. But nothing like what Patricia was to endure. Instead of gradually curing her, the INH sent her into severe allergic reaction, at one point causing her to be hospitalized at St. Paul for nearly a week. As doctors tried to figure out what was going wrong, she developed hepatitis and anemia.

She didn’t know it, but her situation was becoming very dangerous-she was on the way to developing MDR (multiple drug resistant)-TB, a fast-spreading mutant that has caused worldwide concern, kills quickly and with 70-90 percent certainty and already accounts for at least 3 percent of all new TB cases in this country. Fortunately, Patricia responded to a combination of secondary drugs, including the standards: PZA (pyrazinamide) and EMB ( ethambutol). Unfortunately, she had to take the first 50 doses not in the form of pills, but daily ’shots in the butt.” Just to polish off the indignity, she had to follow up the shots with monthly visits to the TB clinic, where, like all patients, she had to cough up sputum, until it became clear and doctors could pronounce her free of the disease.

“It was like being a leper,” she says, now cured.

For [he first two weeks after diagnosis in August 1991, the period during which she could have been contagious to others (medication takes 7-10 days to kick in), she stayed in her house or wore a mask if she went out. “The last thing you want to do is give it to someone else,” she says. State-mandated contact tracing, the same as if you had AIDS or an STD. required the health department to skin-test relatives and friends. Persons exposed to contagious TB have a one in four chance of taking in the basic germ. The 10 percent chance the germ will turn active, and communicable, exists for the rest of their lives. Fortunately, none of the couple’s relatives was infected.

She and Charlie moved to North Dallas a year ago. During their recuperation, they were tired all the time-practically newly-weds and so sick they didn’t even want to have sex. “We had nobody to talk to. except doctors,” she remembers. “One day I talked to a lady in the waiting room like myself. I was craving to talk to someone I could relate to. I just wanted to be normal again.”

Charlie’s craving was to get back to work. You can’t be fired for having TB, though nervous employers often come up with “other” reasons easily enough, and commonly do. Charlie quit his old job, though, because he was just too exhausted from lighting the disease. His plan now is to start up his own brokerage. It’ll be easier than telling a new employer that, although now fully cured, he has had TB. Unlike Patricia, who seems to have pulled through the ordeal emotionally, Charlie still tries to put together a puzzle that will never have all the pieces. “I just didn’t think people had TB anymore,” he often told Patricia. “I thought they got rid of it” Now he laughs grimly. “But anybody can get it. Are you gonna tell me because you live in North Dallas you’re not going to get it?” It’s a rhetorical question.

The stunning return of TB in America, which The Journal of the American Medical Association calls “frightening,” statistically began in 1985, when decades of steady decline in new cases quietly reversed course. TB victims are now increasing at an average of 16 percent a year, producing 26,000 new cases in 1991 alone. The total is still far lower than the 84,000 cases in the last peak year of 1953, when national reporting became standardized, but the rate of acceleration, and the favorable conditions of growth, have caused widespread concern. Predicting a doubling of the volume of new cases-to 50,000 annually-by the end of the decade, the American Lung Association says the country is “sitting on a time bomb.” Dr. Dixie Snider, director of the TB division of the Centers for Disease Control, says the new epidemic is not only more potentially destructive than the 19th-century version, but is “out of control.” Prodded by the CDC. Congress is seeking $74.3 million in emergency appropriations to combat the disease, although the Bush administration has requested only S35 million. Either sum is much larger than the $12 million allotted for 1992.

For a number of reasons, both Dallas and Texas are near ground zero. With 2.525 new cases last year, a 20 percent increase in the past decade, Texas, with a $9.5 million TB control budget, has moved into the unenviable fourth spot for states (after New York, California and Florida) hardest hit by the new wave of TB. It’s been a quick rise-in 1990. we were ranked seventh. Dallas County, with 301 new cases last year alone and a cumulative total of about 4,000 persons under preventative or curative treatment, is fourth within Texas, behind Harris, El Paso and Travis counties.

Statistics show the impact even more clearly. The national incidence of new TB cases is currently measured at 10.4 cases per 100,000 persons. The comparable figure in Texas is [4.6, a strong rise from 11 as recently as in 1989. The level in Dallas County is even higher: 16.1. Within the city the rate has zoomed higher still-to 213. That’s double the national incidence, and positions Dallas number 20 among the nation’s 64 most TB-prone cities.Cities bear the brunt of the plague because, as with most infectious diseases, they contain larger quantities of the most contagious or vulnerable people. Chief among the victims for the new TB are HIV/AIDS patients, in whom the resurgence was first manifested and for whom the epidemic has tightened like a noose around a neck. An “opportunistic” disease, TB attacks at any sign of bodily weakness, from stress to diabetes to cancer. Immune system suppressants such as HIV and AIDS are tailor-made. The precise incidence of tuberculosis among the country’s estimated 1.5 million HIV positive persons is difficult to obtain, because of privacy issues, but in New York, for example, it is thought to be as high as 40 percent. Recent published data from West Africa, where H?V is endemic, shows TB to be the cause of 35 percent of HIV-related deaths in one country.

To the HIV/AIDS community in Dallas, the recurrence of TB is especially disheartening. For the last three years, the incidence of AIDS-now about 650 new annual cases-has ’leveled off,” according to the county health department. But with an expanded definition of AIDS, now including pulmonary TB as one of the 26 manifestations of the disease, the number of new AIDS patients in the county is expected to rise to perhaps 2,000 within the coming year. The redefinition to include TB has long been sought by AIDS activists so that victims can qualify for certain kinds of treatment. And while the higher numbers from the expanded definition are shocking, they are far more indicative of the potential devastation if the TB outbreak continues unchecked. Although TB in HIV positive patients is generally treatable, the odds drop fast. Furthermore, an HIV patient carrying the dormant TB germ is about 100 times as likely to develop active TB as are otherwise healhy persons-the chances accumulate 10 percent each year after initial infection. And MDR-TB, exceptionally lethal even among the general population, is almost always a killer for HIV/AIDS victims.

The biggest single factor in the spread of TB in Dallas, however, is not its relation to AIDS. For Dallas, destiny is geography, not sexuality. The most rapid rates of increase in the county are among the foreign-born. Of 5,027 persons who reported to the county TB clinic near Parkland Hospital in 1991 for registration or testing, 41 percent were classified as “refugees.” Most were members of the relatively recent flood of Southeast Asians. The second biggest group were Hispanics- Mexicans and Central Americans.

The reason for the impact of the foreigners is so simple we tend to forget it. TB may have been on the wane in America, but it has remained the worldwide plague of first ranking. According to the World Health Organization (WHO). 20 million people have active TB, with 8 million new cases arising each year. WHO says nearly 3 million die annually from TB, making it the most lethal infectious disease on the planet. With so much of it out there, it can only have been a matter of time until it got back here.

Not surprisingly, the biggest overall rates of increase in new TB cases in Texas are found in El Paso (E! Paso) and Nueces (Corpus Christi) counties, with 43 percent and 26 percent, respectively, Dallas County, in comparison, had a 5.4 percent increase last year; Harris County, the number one TB target in the state and number seven in the nation, rose 6.1 percent last year. Those latter Figures are smaller, but addicted or prostitutes, on the dangers to themselves and others caused by TB. “But anyone can get it. Maybe a solid citizen who spends the night in the tank on a DW1 charge and then doesn’t tell his wife, and so on. It’s insidious how the disease can spread.”

Jails are perfect examples.

No one knows the exact incidence of TB in the five Dallas County jails, but there’s a sophisticated guess; In the state prisons, where the population is more stable, a rate of 106 new cases of active TB per 100,000 was reported for 1991. The CDC estimates that many correction facilities have infection rates-not necessarily active cases- of up to 20 percent. The lack of reliable data in the jail is typical of the kinds of special problems TB generates. An estimated 90 percent of the 12,000 detainees who go through intake each month are released within 72 hours. Since it takes three days for a skin test to show results, there is no way to know how many of the approximately 6,000 people in jail at any one time are either infected or contagious.

Last summer. Dr. Philip Jenkins, medical director of the Dallas County jails, put a 30-year-old South Dallas black male, HIV positive and homeless, on the bus to Tyler, where the state operates a small TB inpatient unit. Jenkins first came across the man because he kept showing up in jail. He’d try to find work, but failing that, would break into coin machines. He’d get caught, go back to jail, and so on. Early on in the cycle, Jenkins gave the man a standard Mantoux skin test and got a positive reaction, confirmed by X-ray. Jenkins put him on medication, but each time, as soon as the man was released, he’d go off the treatment.

To break the pattern, save the man’s life and reduce the possibility of exposing others, Jenkins called the hospital in Tyler and arranged for the man to be taken in. Witfi the demise of TB in America, most sanitariums have vanished. There are none in Texas, and only two full-scale chest hospitals, with quarantine capabilities, in San Antonio and Harlingen. The state has the power to order an infectious patient who won’t follow treatment to one of the chest hospitals-two MDR-TB jail inmates were sent to San Antonio from Dallas in the past year-but so far that’s relatively rare. The more frequent problem is getting a space for those who volunteer.

But at last, for this man, everything was set. But, like the odds against getting TB, the efficiency of the system failed in the clinch. Deputies didn’t get the word, and the man was inadvertently released from Lew Sterrett at midnight, standard procedure for departing inmates. He got lost addicted or prostitutes, on the dangers to themselves and others caused by TB. “But anyone can get it. Maybe a solid citizen who spends the night in the tank on a DW1 charge and then doesn’t tell his wife, and so on. It’s insidious how the disease can spread.”

Jails are perfect examples.

No one knows the exact incidence of TB in the five Dallas County jails, but there’s a sophisticated guess; In the state prisons, where the population is more stable, a rate of 106 new cases of active TB per 100,000 was reported for 1991. The CDC estimates that many correction facilities have infection rates-not necessarily active cases- of up to 20 percent. The lack of reliable data in the jail is typical of the kinds of special problems TB generates. An estimated 90 percent of the 12,000 detainees who go through intake each month are released within 72 hours. Since it takes three days for a skin test to show results, there is no way to know how many of the approximately 6,000 people in jail at any one time are either infected or contagious.

Last summer. Dr. Philip Jenkins, medical director of the Dallas County jails, put a 30-year-old South Dallas black male, HIV positive and homeless, on the bus to Tyler, where the state operates a small TB inpatient unit. Jenkins first came across the man because he kept showing up in jail. He’d try to find work, but failing that, would break into coin machines. He’d get caught, go back to jail, and so on. Early on in the cycle, Jenkins gave the man a standard Mantoux skin test and got a positive reaction, confirmed by X-ray. Jenkins put him on medication, but each time, as soon as the man was released, he’d go off the treatment.

To break the pattern, save the man’s life and reduce the possibility of exposing others, Jenkins called the hospital in Tyler and arranged for the man to be taken in. Witfi the demise of TB in America, most sanitariums have vanished. There are none in Texas, and only two full-scale chest hospitals, with quarantine capabilities, in San Antonio and Harlingen. The state has the power to order an infectious patient who won’t follow treatment to one of the chest hospitals-two MDR-TB jail inmates were sent to San Antonio from Dallas in the past year-but so far that’s relatively rare. The more frequent problem is getting a space for those who volunteer.

But at last, for this man, everything was set. But, like the odds against getting TB, the efficiency of the system failed in the clinch. Deputies didn’t get the word, and the man was inadvertently released from Lew Sterrett at midnight, standard procedure for departing inmates. He got lost again-till his next arrest. Again, Jenkins made arrangements. He personally met the man at 6 a.m. outside the jail and waited until a county TB outreach worker drove the man to the bus station and put him on a bus. Watched the door close, watched the bus drive away. Now in Tyler, die man has a place to stay–finding shelter for homeless or mentally ill TB patients is also part of the task-and attendants to see that he completes his treatment. He is recovering. But neither he, nor anyone else, has any idea how many people he may have exposed along the way on the streets, among relatives, at shelters, or in the cell block.

But there is a way to measure at least part of the exposure. TB nurse Diana Saldana and a dozen other field workers who are part of the 30-person staff at the county clinic spend a good deal of time not only treating the current caseload of 3,500 preventative and 500 curative TB patients, but finding them. It is difficult work, often leading to people who can barely cope with life, much less a horrible disease. Recently, while treating a young Hispanic day laborer who’d come down with TB, Saldana deduced that he had probably contracted me germ from a transient co-worker. She had to find him, and did, holed up in a cheap, Industrial corridor motel. A 56-year-old Anglo, he was drinking, coughing, scared. One lung was already consumed, and he was so emaciated he looked like he had AIDS, which advanced TB symptoms can mimic.

Saldana, whose only protection, like most TB workers, is a skin test each six months, was able to get the man to Parkland to begin a yearlong regimen of live-saving treatment, but that was only the start. She had to go back to the man’s favorite liquor store and skin-test not only the employees, but me homeless who hung around. The tests were all negative, but Saldana’s experience was that if tested again in a month they would convert, or become positive. And then she could have to go back and tell diem. It was getting to be a part of her job that she hated as much as the ongoing risks to her own health.

She still remembers the 30-year-old Turkish mother of two children standing on her front porch, screaming at Saldana that she couldn’t possibly have TB. That nobody got it anymore. That she’d been vaccinated (with the BCG vaccine, only used in foreign countries, and considered unreliable). But the skin test was positive. Not only that, as Saldana backtracked the trail of infection, she drew positive skin tests from 15 out of 30 co-workers at the upscale Dallas hotel where the woman was employed. The index case turned out to be a young, alcoholic Hispanic male, who also eventually infected his own relatives back in Houston, including two children. He might never have been diagnosed had he not been arrested for DWI and, while in jail, been discovered to have the active disease.

Saldana likes her work and thinks it important, but her husband wants her to get another job. You can see his point. Health-care workers are among the most endangered by the new epidemic. At San Francisco General Hospital, 4 percent of the house staff recently tested positive for TB. North Central Bronx Hospital in New York reported 60 new positive skin tests among employees in a one-month period last January. In 1990, 10 of 28 health care workers on an HIV ward at a Florida hospital changed from negative to positive skin tests.

Nor is it just a problem somewhere else. In the past year, 80 employees at Parkland Memorial Hospital have shown positive skin tests, and it was at Parkland ER in 1983 that one of the most frightening proofs of the explosive ability of TB to spread occurred. Seven members of the Parkland emergency room staff, including one doctor, developed active TB after working on an acutely ill 70-year-old male alcoholic brought in for resuscitation. An additional 47 hospital employees exposed to the man developed positive skin tests- though not active disease. One lupus patient exposed to nurses and aides who had attended the man developed TB and subsequently died, with TB a contributing cause. The man himself died two months later in Parkland’s intensive care unit.

A subsequent study co-authored by Dr. Charles Haley (Robert’s brother), now the county’s chief epidemiologist, indicated that although the man’s condition was so acute-he was coughing up orange-red sputum, a spray of blood and lung tissue- that the level of exposure was exaggerated, the infection’s spread was also traceable to simple unpreparedness. In 1983, TB in America was thought to be in remission-most control and research programs had been cut back or defunded, along with many public health programs under Reagan-era budget slashing. Even though the Parkland personnel knew the man was a TB patient, no special precautions were taken. Extremely contagious lung matter from an intubation tube spattered around a trauma room after being removed from the man’s throat. The ER itself lacked safeguards. Air recirculated so slowly that it in effect recirculated TB germs inside the rooms and corridors. Old-style tie-back surgical face masks, loose around the edges, were useless in filtering out bacteria.

Since then. Parkland, like many hard-hit inner-city hospitals, has gotten the message. Forty-eight rooms have now been designed for negative air flow, which means disease-laden air is evacuated and dumped outside, where germs quickly die. The hospital’s AIDS clinic also has two negative vented rooms, and more such rooms are being considered. Ultraviolet lighting, which neutralizes TB germs, has also been placed in the rooms. The costs are not small. To take one example, high nitration masks cost about 75 cents each- the old ones were about 25 cents. Each health-care worker may use several masks a day, and Parkland has nearly 6,000 employees.

Baylor. St. Paul and Methodist have also set up rooms and initiated modest TB education programs for staff. The jail system has just received a $177,956 grant from the CDC to set up a program to test, identify and keep track of inmates with TB. Limited testing exists throughout the city’s public and private sectors. The DISD. as well as most hospitals and health-care facilities, require employment TB skin-testing. So do police and fire departments.

But TB tests are not widely administered in corporations, nor are they required for most students or for all city employees. Some day-care centers require employment TB testing; others do not. Despite the clear and present danger, efforts to isolate and treat TB in the city are minimal. Even in hospitals, post-employment testing is voluntary, with a dismally low record of turnout. Doctors, who often skin-test positive, are some of the worst avoiders. To compare the situation, the state health department ran short of skin-test supplies in October, forcing Dallas and many other cities to temporarily curtail routing TB screening. Moreover. TB precautions tend to get lost amid even more stringent guidelines concerning AIDS and hepatitis-B prevention.

The problem is, you can”t really “prevent” TB. Despite the proven ability of the disease to fan out from a single index case to infect dozens of others, there is no reliable immunization, as there is for measles, polio or hepatitis.

The tubercular germ, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a kind of bacterial sticker burr. A person with pulmonary TB. which accounts for 90 percent of all cases and is the most infectious kind except for the relatively rare TB of the larynx, spreads die TB bacteria by coughing. We all know how coughs spread out through a room-hundreds of feel at a time. That’s why we’re supposed to cover our mouths. But we don’t always do so. If we don’t and we have TB, we spew out a mist of droplets, some of which contain a TB bacillus of about 5 microns diameter. The TB droplet evaporates instantly to an even tinier nuclei, which may hang around for hours in a room or a hallway, a bus or a hotel lobby–or a waiting room.

People in such rooms breathe in about 20 cubic feel of air per hour. Normally, a tubercular person generates about one infectious particle per 11,000 cubic feet of air, but extreme cases can pump out one per 200 cubic feel. A small room with a lot of people increases the odds that somebody will draw the wrong breath. The odds are one in four that if exposed to active TB, you’ll pick up the germ. “Exposure’’- in theory’-requires about 80 hours of consistent space-sharing required to put an otherwise healthy person at risk. That, or something very intense, like being coughed upon directly-say. if you’re a cop, or an EMS worker, Or being weakened by AIDS, age, diabetes or even stress. Odds or not, an estimated 10-15 million Americans (about 100,000 in Dallas County) are TB “carriers,” which means the germ is in their bodies.

That may never cause a problem. Thriving on oxygen, the inhaled TB germ goes right to the lung. There, it is imbedded in a kind of hardened cocoon after being attacked and neutralized by while blood cells. Ninety percent of the time it remains dormant. As such, it is neither dangerous nor infectious. But it never really goes away. In a Fort Worth case, a 41-year-old man diagnosed with TB in 1971 suffered six relapses before dying of TB in 1987. His problem was that he wouldn’t stick with his treatment. Sixty of his 127 extended family members, living across the country from Texas to Pennsylvania, developed positive skin tests. Thirty were children.

The best way not to get TB is simply not to be around it. The second best route is to treat it early and thoroughly. State law requires, and pays for, “curative” treatment for active cases, detected by skin test and confirmed by X-ray and sputum culture. It also funds, but does not mandate, “preventative” therapy for people who have positive skin tests but who show negative X-rays. Preventative treatment is designed to keep the germ from activating. The minimum six-month treatment provides a 78 percent assurance [hat the dormant germ will stay that way, according to Dr. Buu Nguyen, medical director of the county TB division. For those who take a full year’s regimen, the odds increase to an almost ironclad 96 percent. Nonetheless, a lot of people play roulette. In Dallas, 20 percent TB, from page 74

of all TB patients fail to comply with the year’s curative treatment and 14 percent fail to complete the six-month preventative program.

Failure to complete treatment, or to get it early, is not only dangerous socially, and medically, but also fiscally. Treatment of an average curative TB case runs about $11,000, including about $300 for the most common drugs. But advanced cases, or those complicated by non-compliance, or those involving the drug-resistant strains, can escalate the price tag to as much as $250,000 per patient.

Both the costs as well as the levels of TB are only likely to increase. The older we get, the more our immune systems deteriorate An estimated 28 percent of all TB cases occur in patients 65 and older, which makes the elderly the largest at-risk group.

A CDC doctor has estimated that half of all TB cases among the elderly go undiagnosed “to the grave.” Nursing homes, where 5 percent of the elderly reside, are especially risky, increasing the chances of catching TB by anywhere from 5 to 30 percent. As the parents and grandparents of the Baby Boom reach their final years, vast numbers of new cases, especially if fueled by an unchecked epidemic this decade, could usher in the new century. “Sure, it can make you paranoid,” says UT/Southwestern’s Dr. Robert Haley. “But it’s like Yossarian said in Catch-22. You’re not paranoid if they really are out to get you.”

Literary allusions are apt. Once upon a time TB was considered a romantic disease. The poet Byron is said to have once remarked, “I should like to die of con-sumption…because ladies would say.,. how interesting he looks in dying.” Pale. thin, a slight flush of low-grade fever -all these TB symptoms were, in the 18th and 19th centuries, considered to be desirable. We remember the more famous victims: Robert Louis Stevenson, Frederic Chopin, the Bront? sisters, Thomas Mann, Henry David Thoreau, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, ’’Doc” Holliday. Eleanor Roosevelt also died of TB, as did Louis Armstrong, who also had throat cancer.

Perhaps we romanticize it even today. Not by celebrating its victims or waxing decadent about the seductions of deathly pallor, but by ignoring it. Like the Go-forths. most of us think TB is “somebody else’s disease.” Only the poor and unfortunate get TB. It only applies to the wrong side of town. Which is what we used to think about AIDS. We were wrong.

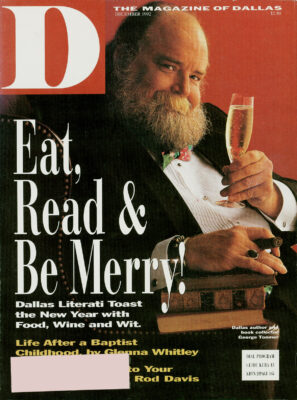

Related Articles

Hot Properties

Hot Property: An Architectural Gem You’ve Probably Driven By But Didn’t Know Was There

It's hidden in plain sight.

By Jessica Otte

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert