“He’s insatiable!” Greer Garson announces from a zebra-skin chair in her Dallas penthouse apartment. “You’ve already taken three shots,” she scolds the photographer.

“I have to take two rolls in case anything happens,” he murmurs back to her.

“I’m not sure that’s very complimentary,1’ she pouts and begins inspecting her nails.

Her poodle, Chi Chi, scampers from her lap, perhaps to examine her own canine digits. Both star’s and dog’s nails are painted pink.

“I guess Chi Chi doesn’t want to be in the picture,” the photographer shrugs.

“Frankly, neither do I,” Garson fires back.

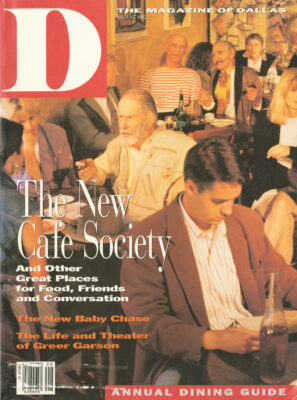

The movie queen, at what biographical sources say is 84 years old, has agreed to a rare portrait sitting and interview on the eve of the opening of the Greer Garson Theatre at SMU. “People say, ’Is she still around?’” Garson sighs with amusement. “I’m a theatrical landmark.”

Her namesake landmark has its ribbon-cutting ceremony to open the Greer Garson Theatre Fortnight Festival Sept. 12 at SMU’s Meadows School of the Arts. Once the dust has settled, sometime around her 85th birthday on Sept. 29, Garson’s $10 million endowment will have given Dallas the Southwest’s only “Shakespearean-thrust” facility. The students of SMU’s theater program will get an invaluable 50,000-square-foot, five-floor laboratory in which to research their art, and audiences will have an intimate 386-seat space in which to watch some of the country’s finest educational theater.

Garson’s involvement with the new facility didn’t end with her donation. She’s been actively involved from the beginning, following each detail right down to knowing the number of lighting positions in the house. “You’re not trying to save me money, are you?” she grills theater instructor and translator Paul Walsh one day over drawings of the electrical design. She knows her stage is a nine-sided platform, 18 by 24 feet. She knows that there are entrances to the stage via the theater’s aisles, as designed by architect Milton Powell.

“I call him my boy genius. 1 saw his first plan and told him, ’It’s very handsome, Milton. But it’s not very interesting. Go back and romanticize it.’” The result is an inter-mitlently recessed outer wall broken by four lighted bays and augmented by an entrance canopy.

“It’s much better now. You see? I was rude and I was right.”

Her facility is modeled on the great Stratford Festival Theatre in Ontario, Canada, where SMU Theatre Division Chairman Cecil O’Neal was a director before coming to Dallas. It also draws on the designs of Minneapolis’ Guthrie Theatre and England’s Chichester Festival Theatre.

Garson is pleased that a woman will direct her theater’s first play: SMU graduate Pamela Berlin, who directed Broadway’s The Cemetery Club and Portland Stage’s A Day in the Death of Joe Egg, will stage A Midsummer Night’s Dream as the Greer Garson Theatre’s inaugural production.

“And the theater’s stage has a nice, high balcony they can use in the show” Garson brags.

For hanging lights?

“For hanging actors.”

TEA WITH GREER GARSON IS ONE JOYOUS afternoon with an elusive sprite who deflects hard questions with peals of laughter.

Why did she stop making films after Disney’s 1967 The Happiest Millionaire?

“That was enough to stop anybody, don’t you think?” But, push her beyond the punch line, try to get something deeper than a good laugh out of the fact that she left the nation’s screens a quarter of a century ago, and she pulls rank on you.

The imperious Garson is suddenly in charge. There’s no reprimand, not even the glimmer of a frown, nothing so vulgar. Just a chill, impossible in the hot Dallas sunlight streaming through her gigantic windows, but palpable, nonetheless. And there’s silence. She awaits the next question, trusting that it will be more to her liking. No hurry. When you’re ready, dear. More tea, meanwhile?

It’s Earl Grey. And her voice is a 10, too. as in No. 10 Downing Street-she’s a dead ringer for Margaret Thatcher. That laugh, however, erases 70 years, floating across the grand piano of her skyline sitting room like an echo of her childhood in Ireland.

“That’s where my grandmother was when she made this,” Garson says as she smooths the folds of a meticulously saved tablecloth under the lea service. White squares of linen are held together by a tiny, box-stitched network of fibers. “She called this ’drawn threadwork.’ Yes, it is beautiful, isn’t it?”

The cloth, like her laugh, is a treasure that all too few have enjoyed lately. Her health has been as unsteady as her box-office popularity had become by the mid-60s. Garson’s physical “setbacks,” as she impatiently calls her ailments, reportedly have included triple bypass surgery and pacemaker implants in recent years. But 50 years ago, she was considered a national treasure.

In the early 1940s. Garson’s Oscar-winning title role in Mrs, Miniver helped rally American sympathy for the British at war. Churchill and Roosevelt encouraged the earliest possible release of the movie to aid the war effort. Garson also promptly outdistanced all other actresses in government bond-selling tours. In Canada, one smitten newspaper reporter gushed that when she came through on the Victory Loan Campaign “morale soared sky-high wherever Miss Garson set her pretty foot.”

She concurs with critics who say that the 1950 The Miniver Story was a decidedly inadequate sequel to the 1942 work. In fect, her fortunes in doting men’s eyes already were beginning to sag with the 1946 Adventure with Clark Gable.

To grasp the actual brevity of Garson’s brilliant career, you must understand that her strongest entries in both London and Tinseltown had been made by the time she was 34. In London, playwright Sylvia Thompson gave her a fairy-tale break and cast her in the lead role in the West End’s 1935 Golden Arrow, opposite Laurence Olivier, who was one year her senior. She loves to tell of how her twisted ankle meant that Olivier had to carry her on stage, an entrance that became increasingly hard for him as raves for her increased and those for Olivier declined. Gar-son went on to do 13 shows in three and a half years in London. Then, defying the counsel even of Noel Coward, who had directed her in Mademoiselle, she answered the siren call of Hollywood and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

After a terrible first year at MGM-Louis B. Mayer was unsure how to cast her-the 1939 Goodbye, Mr. Chips rescued her. She was with Olivier again in Pride and Prejudice in 1940, then went on to Blossoms in the Dust (1941), When Ladies Meet (1941), Mrs. Miniver (1942), Random Harvest (1942) and a few other well-received vehicles including Madame Curie (1943), Julius Caesar (1953) and Sunrise at Campobello (1960).

But such works as Strange Lady in Town (1955), Pepe (1960) with Mexican comedian Cantinflas and The Singing Nun (1966) took their toll on her screen reputation.

She knows this. She also knows she doesn’t have to talk about it. Nor is there any shame in it. The business is voracious, the greatest stars are its caviar. Her once-jealous colleague, the mighty Olivier himself, chose a different course and worked as long as he could-the result being some sadly dubious late-life projects, a spectacle Garson painstakingly has avoided.

What she still has are priceless memories. Say Bernard Shaw to her-after all, she toured his Too True to Be Good in the English provinces as a young woman:

“Too True was the beginning of my long, intermittent friendship with Mr. Shaw. When I went to Hollywood, he said, ’You’re an actress and you’re giving up the theater to go and play with those movie-what did he call them?-’those movie lanterns.’ I had a late tea, a sort of supper with him on his last Christmas Eve in 1949. He died rather soon after that-no connection, I trust.” Among Garson’s personal anecdotes that are definitely off-limits are her two early marriages. To mention them is to watch her clam up.

In 1933, she was married to Edward Alec Abbot Snelson, a British attache”. She left him five weeks later, saying she didn’t want to go to India with him. Years later he sued her on grounds of desertion-the American divorce she had obtained wasn’t recognized in England.

Garson’s marriage to actor Richard Ney, who had played her son in was another short-lived relationship, and Ney was to go on to a monumentally embarrassing destiny: He wrote and produced a musical comedy on Broadway in 1958 called Portofino. So bad was the show, which ran for only three performances, that the New York Post’s Richard Watts Jr. called it “an epoch-making disaster”; the Journal-American’s John McClain proclaimed it “a catastrophe all around”; and Herald Tribune critic Walter Kerr, generally beloved for his forgiving reviews, concluded, “.. Nor will I say that Portofino is the worst musical ever produced, because I’ve only been seeing musicals since 1919.”

But Garson’s initial bad luck in romance was replaced with a grand slam. Her third husband, the late E.E. “Buddy” Fogelson, is the only husband she will discuss, and since her marriage to him she prefers to be Railed Mrs. Fogelson.

“He was the greatest adventure,” she says of the attorney/oilman/rancher/philanthro-liist. “I’m glad he wasn’t an actor. I’d never want to be on stage with him. They’d have to expand the old adage to say, ’Never play with la baby, an animal or E.E. Fogelson.’”

Garson and Fogelson were introduced on la Hollywood set by Peter Lawfbrd. She’s not sure which film she was working on at the time. “I have this aversion to years and dates.” In all likelihood, however, it was Julia Misbehaves, a 1948 film that gave Gar- son an unusual chance to kick up her heels. Lawford was in the cast with her.

Fogelson, concerned about the acrobatics she was doing in the film, gave her a gold medallion, ringed with pearls. She wears it today. It’s a St. Genesius, the patron saint of actors. Theater lore dictates that its protec- tion is good only if a St, Genesius is given to you-you cannot arm yourself with one.

They were married in ’49, and Garson became an American citizen in Abilene in 1951. “With him, it was love at first sight, apparently. With me, I was intrigued, but I was very wary of falling in love or any of that nonsense.”

GARSON AND FOGELSON NEVER HAD children, but until his death in 1987, their 5,556-acre Forked Lightning Ranch in New Mexico was their pride and joy-and home to Garson’s favorite horse, Ho-Hum Silver.

“My equestrian skills were minimal.”

The Fogelsons’ charitable works, however, weren’t.

The couple made their ranch a wildlife refuge and were repeatedly recognized by the Department of the Interior. In 1979, they endowed a scholarship fund for theater students at SMU, and for two decades Garson maintained a college scholarship program for girls at Pecos High School in New Mexico. She also endowed a fund for student awards at the chilly, wind-swept New University of Ulster, near her birthplace in Northern Ireland. Next to the Fogelson Library Center at The College of Santa Fe, she created the Greer Garson Theatre Center, a complex crowned in 1990 with her $3 million donation for a film and video training facility, the Greer Garson Communications Center and Studios.

Locally, her largess has reached to the Fogelson Forum, a medical education center at Presbyterian Hospital; Fogelson Pavilion, the dining area at the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center; the Dallas Arboretum’s Fogelson Fountain; downtown’s Pegasus Plaza; and now, the Greer Garson Theatre- which already is affectionately being called “the Greer” by actors.

One of Garson’s biggest supporters is her friend Eugene Bonelli, dean of the Meadows School and vice president of artistic development for the Dallas Symphony. With him she talks about her theater. Ramps going into the structure mean she can have a wheelchair tour of the construction site, a hard-hat ride she anticipates with obvious impatience. She wants to see the balcony that’s designed into the theater’s stage plans for “inner above” scenes, as they’re called in Shakespeare terms-moments from classic dramatic literature such as the morning-after “What light through yonder window breaks?” scene from Romeo and Juliet.

The thought of those actors being students suddenly triggers a memory. She’s been talking about how actors on her new stage will act “north, south, east and west,” This reporter’s rejoinder in English, “You mean ’acting with your back,’ as they say,” has led her to a French phrase from her years of stage acting in the West End.

She’s got it: “Les effets du dos!”

When she was a child, her mother took her to Paris where they saw Maurice Chevalier on stage. To this day, Garson can sing the French lyrics to his song “How To Plant Cabbages” from that show. Years later, Chevalier saw her on stage in London. He visited her dressing room where she sang his cabbage song to him. “And he spoke about some move I’d made at one spot in the lot- he’d seen les effets du dos in my work.”

Another memory of childhood has returned, too, though not a happy one. Garson was often ill as a girl. Changes in season always meant severe bronchitis until the age of 15. She was considered frail by schoolmates, left out of their games and put to bed for weeks at a time.

She moved from the north of Ireland to London with her widowed mother while still very young-they’d visit her grandmother when homesick for the Emerald Isle. A scholarship student in French and 18th-century literature at the University of London, she parlayed secretarial skills into marketing research in advertising. But she had a friend introduce her to a director with the Birmingham Repertory Theater in 1932 and made her stage debut in Elmer Rice’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Street Scene.

“I played Kate, the self-sacrificing older sister. Gave up her engagement and chance at personal happiness to continue teaching and supporting her young brother. Good girl, Dull part.”

It was to be her lot, in most roles, to play strong-willed, high-principled women. She insists that her own life of good works was never an attempt to fill the shoes of the saintly creatures she played on celluloid, but the world has rushed to honor her with a hefty string of awards: the American-Scottish Foundation’s Wallace Award for Excellence, the New Mexico Governor’s Award for contributions to the arts, the 1988 USA Film Festival’s Master Screen Artist Award, the 1988 Golda Meir Award, the 1991 Jas. K. Wilson Award for contributions to Dallas’ arts, the 1991 Dallas Times Herald Jim Chambers Newsboy Award and the Medal of Distinction from the Meadows School at SMU, as well as the university’s honorary Doctor of Arts degree.

Thanks to SMU’s Southwest Film/Video Archives, the opening in September will include a comprehensive Greer Garson film festival. Oddly, she remembers only 11 films-“seven with some pride and four with loathing.” In fact, she made 25 films between 1939 and 1967.

“Oh, there were 25?” she asks, momentarily dumbfounded. Then, trouper that she is, she decides to barter. “All right, I’ll allow there were maybe 22.”

Part of the Greer Garson Theatre Fortnight Festival will include Shakespearean panel discussions featuring members of the Executive Committee of the International Association of Theatre Critics.

“We’re bringing them here to see your Midsummer and your theater,” an SMU friend tells her.

“And maybe me,” Garson says wistfully.