WHENEVER GEORGE W. Bush goes out on the rub-ber chicken trail-and these days that’s a couple of times a week-he delivers what he likes to call his “Baseball, Apple Pie and the First Family” speech. First there’s a nod to Mom (“I know you would have liked to have the most famous Bush here tonight, but my mother was busy”); a crack at Dad (“I said, ’Dad, that’s a hell of a way to send a trade message to the Japanese’”); a brief political commercial (“I know I’m here to talk about baseball, but I need to help the Ol’ Man stay employed”); some poetics about baseball (“The reason people can relate to baseball is that it’s the sport that normal-sized people can play”); a rah-rah for the Rangers (“1992 is the Rangers’ year. This is the year we’re going to win the pennant”); a cheery promise to make it more expensive to watch the team play (“We’re gonna build the greatest new ballpark in the world-and we’ll double the number of premium seats that you can buy”); a slap at the sportswriters (“We’re accused of having some weird business notions-yeah, we want revenues to equal our expenses”); and he’s outta there.

Well, almost. He would be outta there, were it not for the dozens of autograph seekers and plain folk who want to chat up the president’s eldest son about his father’s health, the Rangers’ new pitcher or whether Barbara Bush might indeed consider coming to Marshall next year as the queen ant in the Fire Ant Festival.

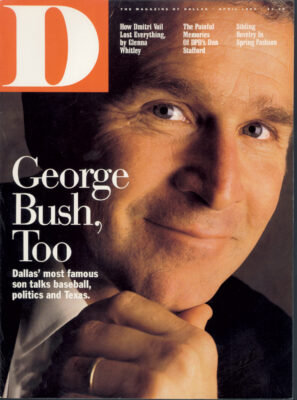

By now. three years after Bush moved to Dallas and bought, with 17 limited partners, controlling interest in the Rangers, the fusion of politics and baseball seems as natural as Ruben Sierra smashing a fast ball into the stands. His role as front man for the Rangers has given him the perfect entree into all echelons of Texas society, not incidentally paving the way for an eventual political career of his own. In fact, it is Texas that has given form to George W. Bush’s emerging political persona. By the time the younger Bush gets around to running for office, not even cartoonist Garry Trudeau will accuse him of laying a false claim to being a Texan.

Bush is not saying when or for what office he will re-enter politics, but his friends say it is inevitable. Soon after he arrived in Dallas, he considered a run for the governor’s mansion, and he played the “will he or won’t he?” game for all it was worth. Back then though, young George was plagued by his own version of the “wimp question” in the form of “but what has the boy done?”

Now George W. Bush has done something. He’s bought a baseball team, restructured its organization, announced elaborate plans for a new ballpark and become a leader of the new guard of club owners calling for economic overhaul in the major leagues. He’s won respect among his fellow Republicans as a shrewd and capable political campaigner and was widely praised for his canny mixture of candor and diplomacy in pushing for the resignation of former White House Chief of Staff John Sununu. He’s lent his name or his time or money to a thousand local points of light, winning even stubborn skeptics as friends.

Yet at the dawn of a new baseball season- the home opener against the California Angels is April 13-and in the heat of his father’s re-election bid, Bush’s already very public life is even more exposed. He is only too aware that his baseball team is one of three franchises in the major leagues never to have won a division pennant. With the economy in a tailspin and presidential challengers bearing down hard on Dad, George the Younger, or G.W. as he is sometimes called, must deal with the constant public criticism of his family, The all-too-real prospect of defeat-in both arenas-has lent an urgency to the younger Bush’s task as genial apologist for the home team.

But the pressure rarely shows. Characteristically self-assured, Bush, when interviewed, breezes through topics ranging from the “claustrophobia” of Cambridge. Mass., where he attended graduate school. to sloppy management practices at Paul Quinn College, where he has served on the board; from the Ruben Sierra salary fight to a Bahraini oil deal recently scandalized in the press; from the twists and turns of his own life to his dreams for his twin daughters. George Bush the Younger’s celebrity is inescapable, but at least for now, there are tangible personal, political, even financial rewards.

“Excuse me, I’m getting Freddie Malek on the phone,” he says one day as I come into his office while he calls the campaign manager for Bush/Quayle ’92. “I’m just trying to show off,” he grins while he waits for an answer. “Freddie? George Jr. How’s everything going?” While he hates the ’”Jr.” label. George tolerates it in Washington. But in Texas, he insists on being called George W.

George is calling Malek, an old political ally of his father and a partner in the Rangers’ ownership group, to provide a view from the hinterlands on the aftermath of his father’s “puking on the prime minister” of Japan. “I think it’s hurt Dad some, but people down here are generally saying that there was good substance to the trip,” he tells Malek. “Buchanan’s up 10 points in the polls? I think that’s old news,” he says. Then, “Freddie, keep me posted.”

From his cluttered office overlooking the North Dallas Tollway, a modest suite strewn with pictures, gifts and memorabilia, George W. plays the role of reassurer to the troops-family, friends, political allies. When you’re in Washington you get myopic, he says. “Real people don’t think that way.” This particular January day he has fielded some 20 phone calls from relatives, Republican party activists, even a couple of congressmen concerned for the campaign.

George’s role at the Rangers is also to mete out reassurances to the public. His duties tend toward what he likes to call “selling tickets’-and that means marketing, media and meeting the fans-at the ballpark as well as on the stump. Unlike some other big-league owners, George attends as many Ranger games as his schedule will allow-last year that meant some 65 home games were spent pumping up the players from his seat behind the dugout, chewing sunflower seeds delivered by the bat boy.

“I want the folks to see me sitting in the same seat they sit in, eating the same popcorn, peeing in the same urinal,” he told Time magazine. He feels the same egalitarian tug toward the players. A frequent fixture at practices and training sessions, George’s chumminess with the likes of Nolan and Bobby and Jose and Pudge is both boyish indulgence and good business sense.

Bush’s tenure with the Rangers dates to May 1989, when outgoing baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth put Bush’s backers together with Dallas investor Edward “Rusty” Rose’s backers to ensure that the franchise would stay in Texas. Though the team won’t disclose the financial breakdown of the $25 million bid, it is widely believed that Bush has very little of his own money in the team-half a million dollars is a frequent guess.

But what George lacked in capital he made up for in star status-and he has put the Rangers on the map, if not in a pennant race. His ease with reporters, second nature to a political brat, is a boon to the team, his partners say. “That’s one of the things I could bring to the club.” Bush says. “I knew there had to be a symbiotic relationship.” Local sports sage Norm Hitzges agrees: “When the owner of the Astros and the owner of the Rangers are in Pittsburgh for a meeting, who do you think gets interviewed?”

Last year, Tom Schieffer. an ex-Democratic ex-state legislator from Fort Worth, was brought in by Bush and Rose to replace Mike Stone as president. Schieffer is not only manager of the club’s day-to-day business and overseer of the new stadium project, but also a limited partner.

Bush doesn’t bun into the “baseball” decisions. “I think the smartest thing an owner can do is to surround himself with the best people and let them make the decisions ” he says. That doesn’t mean, however, that Bush wouldn’t like to meddle in Les Affaires du Valentine. According to Bush, team manager Bobby Valentine-a seven-season non-contender-’has done a good job with what he’s been given. The point is you want to take as much heat off of your front office as you can so they can make good decisions that are in the best long-term interests of the club. We will always evaluate him on the basis of how well he does with what he has.”

Bush was a self-described fanatical Little Leaguer growing up in Midland and professes a lifelong love of the sport. Norm Hitzges once tested him on that. “I had him on a talk show on HSE one time and so I said to him, ’Yeah, George, so just how big of a in were you?’ And he says, big enough to remember the lineup of the 1950 New York Giants. And he proceeds to name them,” Hitzges continues, his voice rising in that familiar, excited pitch, “to…a…man! And he was absolutely correct-no notes or anything!”

The feet that baseball is the national pastime allows Bush to bask in the public eye while he builds a political base, “I’m out there all the time,” he says, leaning back in his chair to reveal eelskin cowboy boots embossed with the Texas flag, “but the topic [baseball] is still relatively safe.”

How safe it will remain is a matter of conjecture. There have been grumblings that the Bush contingent is too cheap to take the Rangers to a championship level. The signing fracas with Ruben Sierra, the Rangers1 most valuable player for four out of the last five seasons, didn’t help. Dallas Morning News columnist Randy Galloway has hammered at the Rangers for not signing Sierra and making “a commitment” to the fans. “If you’re going to be an owner today in the major leagues,” Galloway says, “you have to play by some pretty outrageous ground rules.”

Bush is, by reputation, exceptionally frugal. But he’s also on a mission to keep the Rangers’ operating budget out of the red. He is beginning to make a name for himself among other owners as one of a new breed pushing to tie player salaries to team revenues. Says Bush: “The New York Yankees make $50 million from their local TV contracts. The Rangers don’t make $50 million with all our sales combined.”

That wouldn’t matter so much, he says, were it not for the A-word: arbitration. The arbitration process, according to Bush, is the sure ruin of major-league baseball as we know it. Arbitrators decide player wages based on the “comps,” or the salaries that other teams are paying to their comparable players. So if the New York Mets just signed Bobby Bonilla, an outfielder, to a five-year, $29-million-a-year contract, that makes Ruben Sierra’s $5 million-a-year request look almost reasonable. ’’It’s the only business in the world,” groans Bush, “where somebody else’s stupid economic decision can end up causing you pain and anguish.”

Nobody predicts that the salary issue will be resolved soon. But if anyone can help accomplish it, Bush can, say his pals. Says Rusty Rose: “I may understand the mistakes being made in baseball as well as George does. But he has the skills to know how to get something done about it.”

DUSK IS JUST BEGINNING TO DARKEN THE tarmac at the Marshall, Texas, airport, and a covey of local dignitaries stands ready to welcome George W. Bush to their town. Shouting to be heard over the clatter of the twin engines, Bush is a one-man stampede. “Hi, I’m George Bush,” he says over and over, his arm extended in a perpetual handshake, a broad grin pasted across his handsome, tanned face.

The welcoming committee from the Chamber of Commerce, which has invited him to town to speak, has been thoughtful enough to arrange for a black stretch limousine, on loan from the funeral parlor, to drive us from the airstrip into town. Bush is crestfallen. He doesn’t like to ride in limos in small Texas towns-for the same reasons that he doesn’t want to wear his tuxedo to meet local reporters at a press conference scheduled in about half an hour. Bush is constantly fighting the patrician image he inherited from a father who sport-fishes in Florida and summers in Maine. If George Jr. is to carve out a political niche of his own, it will be as a Texan-and not one who flies in four or five times a year to glad-hand millionaires and shoot quail.

When asked “How are you different from your dad?” George W. once popped back: “He attended Greenwich Country Day and went to San Jacinto Junior High School in Midland, Texas.”

That’s true, sort of. The Bushes’ famous uprooting to Texas took place when George, born in 1946 in New Haven, Conn., was 2 years old. Their destination was Midland, where George Herbert Walker Bush would scrape together an oil exploration firm that he would later sell for more than $1 million. When the Bushes’ first-born was 16, he was shipped off to Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass.-about as far in spirit from a Midland junior high as you can get.

Clay Johnson, a Dallas friend who met George at Andover, then went on to room with him for four years at Yale, remembers his friend as outgoing and likable, a well-rounded if unexceptional student. George played a lot of sports-none of them particularly well-and became a cheerleader, head cheerleader, as a matter of fact. This is not something he likes to discuss. “Texans have a hard time relating to male cheerleaders,” he says.

Johnson and Bush joined the same fraternity, and Johnson remembers an incident that he believes is particularly telling. As pledges, they were crammed into a room “being told what awful pieces of humanity we were,” when the pledge master demanded that the freshmen stand up one by one and reel off their 54 brothers’ names. “Most of the guys didn’t know more than eight or 10 names ” Johnson says. “George stood up and rattled off all 54 names. I attribute that not to mental ability but to an interest.”

George was at Andover and Yale during the ’60s, an era he describes as “a real cynical period.” The counterculture intellec-tualism he saw burgeoning on the East Coast struck him as stultifying. “I saw an intellectual arrogance I hope I never have,” he says.

Few would accuse Bush of that. His strengths, in fact, are his people skills, not his ideas. Though he calls himself a conservative. Bush doesn’t spend a lot of time venting about abortion, or health care, or even Democrats. Like his father, he seems drawn to politics by a sense of the family’s destiny as leaders, not by ideology.

At 45, George seems at ease with his place as the eldest son of the president, though there was a time in his life when he would have found the celebrity difficult to handle. It was the five-year span between college and graduate school, what he calls his nomadic period. He learned to fly airplanes in the Air National Guard, worked with wayward inner-city Houston youth, tried a job in an agri-business company, drank and smoked a lot, played hard, chased women. He has said he may have been trying to prove something to his father But where another son might have ended up in disaster, George ended up at Harvard Business School.

ONE BY ONE. THE CANDIDATES STOOD before their voters, promising a better tomorrow. Only two of the speakers could claim much in the way of political credentials-Jenna and Barbara Bush, twin 10-year-olds and D1SD fourth-graders vying respectively for student council treasurer and secretary. Jenna’s campaign theme featuring Uncle Sam was fashioned hastily after she got caught attempting to rework her father’s antique political button collection for her own use. Barbara ran on an old standby: “Elect the lean, mean, green fighting machine,” playing off the school colors,

Sitting in the auditorium with his wife, George smiled along with the rest of the crowd-but not for long. When the votes were counted, Jenna and Barbara would add their own footnote to the family political stats: Like their father and grandfather before them, their first political races ended in defeat.

In the well-documented lore of Bushdom, it is said that Bushes don’t like to lose. While Jenna and Barbara didn’t particularly seem to mind, Dad and Granddad mind-a lot. George the father lost his first race for the U.S. Senate in 1964. George the son lost his only election bid, a contest for the Midland congressional seat in ’78.

The race was memorable for its grueling primary-one of Bush’s opponents was a popular mayor of Odessa-and the fact that George had just married Midland librarian Laura Welch. The two spent their honeymoon on the campaign trail. Bush eked out a victory and went on to face Kent Hance (then a Democrat, later a Republican candidate for governor) in the general election. He lost by a narrow margin. The campaign left Bush with at least one lasting lesson: Hance had used Bush’s ties to Yale and Harvard against him, portraying himself as the true Texan in the race. George has vowed that will never happen again.

Despite his desire to distance himself from his upper-crust roots, there are many similarities between the son and the father. Both went to Phillips and Yale, both flew military aircraft, both started oil companies in Midland. The son was drawn to Midland, he says, because of the way it made him feel (“expansive”), because of the people (“In Midland, people judge you by who you are, not the cut of your cloth”) and because he believed that, in 1974, the oil business was just about to boom (“I could smell something was happening in Midland”),

It was, and George Bush was clever enough to combine hard digging with his family’s connections and a natural sales talent to build a string of oil businesses that he would sell at a considerable profit. In the mid-’80s, when the oil bust seemed inevitable, he found a buyer in Harken Energy Corp., now headquartered in Grand Prairie. Harken absorbed Spectrum 7, Bush’s company, giving George about a 1 percent interest in the new firm. He also became a director and a consultant at $120,000 a year (the amount was later reduced to $50,000).

The First Son’s relationship with Harken would have been unremarkable had it not been for a potentially lucrative drilling contract with the Persian Gulf emirate of Bahrain. Bahrain sits between two of the world’s largest oil and gas fields but has not had a gusher itself since the 1930s. Recently, seismic surveys suggest an untapped oil field may exist offshore. That discovery set off a bidding war for the right to drill there,

a war eventually won by Harken, backed by the Bass brothers of Fort Worth.

Bush says he lobbied against the Bahraini deal, arguing that Harken was too small to drill in the Middle East. But several dogged reporters smelled a sweetheart deal and are determined to link it to the White House. Published reports have appeared in the Texas Observer and Time magazine. The big blow came last December in a frontpage story in The Wall Street Journal that not only insinuated that the Bahraini deal with little Texas-based Harken was too odd to be true, but drew hazy connections between Harken, Bahraini officials and that most evil of financial empires-BCCI. Though a previous newspaper article had gone so far as to suggest that President Bush sent troops to the Persian Gulf to protect his son’s oil investments there, the Journal took pains to emphasize that Bush the son was not suspected of using his clout at the White House. Almost as bad, though, was the implication that he was a patsy, used by the Bahrainis as a means of access to the U.S. government.

Though Bush admits that if Harken strikes oil, the price of the stock will soar-he now owns a little over 100,000 shares-he does not believe it is coincidental that the flap surfaced on the eve of an election campaign. The Journal piece infuriated him, but he is philosophical about it: “The best thing is that the Wall Street Journal had three reporters scouring all over the Middle East. The thing was exhaustively researched, and it’s over. And there was no “there’ there.”

Bush’s frequent rage at the media earned him a reputation as thin-skinned during the 1988 presidential campaign, when he moved to Washington to be closer to the action. His loathing for conservative columnist and frequent Bush-basher George Will, whom he dismisses as “on a personal vendetta for having been denied social access to the White House,” comes up again and again. And the son says “Doonesbury” creator Garry Trudeau, who thinks so little of the president’s intellect that he depicts him as air, is riddled with a guilt complex.

Bush served his father’s first election campaign as the family spy among the hired guns. The assignment came up at an early strategy session at Camp David with the Bush sons and Republican strategists like Lee Atwater. “I just sort of blurted out that I questioned Atwater’s loyalty to my father.” George recalls. At the time, one of Atwater’s business partners was working on Jack Kemp’s campaign. Bush remembers that after the meeting broke up, Atwater cornered him and his brother Jeb, saying, “Look, were you guys serious about that?” “My brother came up with a great line then,” says George. “He said, “Look, if there’s a hand grenade near our Dad, we want you on it first.’” George then added his own thoughts. “I said, ’Look, for you it’s a business, but to us it’s a life.’”

At Atwater’s suggestion, George moved into the campaign headquarters and worked with the day-to-day team. Though he won’t be that involved this time around, his father made it clear that George was a player when he named his ’92 campaign team, The younger Bush will stay in Texas as a surrogate, stumping and advising his father with the candor that has become his trademark. George believes that he “earned his spurs” in ’88. “How many times,” he asks, “do you have an opportunity to go into combat with someone you love?”

George’s reverence for his father is so polished that it virtually shines. The man who is embarrassed to admit he was once a cheerleader is not ashamed to confess a profound love and respect for his parents. “When people attack his dad,” says friend Clay Johnson, “he can get ballistic.”

Washington was not George’s idea of a fun place to live. But he has carved an identity for himself there, at least for as long as his father occupies the White House. The president, say insiders, has increasingly come to rely on his son’s advice and ability to negotiate freely among the conflicting personalities surrounding him. The Sununu affair proves the point. George got involved, he says, when “Dad asked me to come up as an unbiased observer to suggest what would be the best organization for the re-election.” Sununu had assumed he would run the campaign from inside the White House, but a lot of Bush players had had it with him, a man with a well-publicized reputation as a petty and petulant tyrant. It was George’s job to make the rounds and report back to his father. It didn’t take long for George to catch on that Sununu was more of a liability than an asset. After briefing his father, he approached the chief gingerly. In conversations that went on for about three weeks, George urged Sununu to accept the fact that his effectiveness had run its course. “That’s one of those no-win jobs that just has a relatively short life.” he says, choosing his words carefully. “’I like John Sununu. I think he was tremendously loyal to my Dad, and my suggestion to him was that he go to the President and offer him several alternatives.” The rest, of course, is history.

What the son proved was that he owns the title of “honest broker,” says Carl Leubsdorf, Washington bureau chief for The Dallas Morning News. “It showed how all presidencies have to have someone whose only interest is in that president. Bush could carry the news about Sununu to his father and not be accused of having any interest of his own.” George himself calls the Sununu affair one of the highlights of his life: “It’s just not that often that you can do something really meaningful to help the president of the United States.”

Despite the trials of the current campaign, Bush is convinced his father will serve another term in the White House, and after that…who knows where his own political trail will lead?

Some have suggested that he might make a run at Governor Ann Richards’ job in 1994, or perhaps the Senate seat occupied by Lloyd Bentsen. Texas party wags view Bush as very much a player over the next decade, should he choose to get into the game.

In the brief time he has spent in Dallas. George W. Bush has already made a mark. The Bushes have been besieged by requests from local boards and non-profils to lend the Bush drawing power to their causes. They have concentrated on a few: Hearts and Hammers, a group that renovates houses with volunteers; the Kent Waldrep National Paralysis Foundation; the Cotton Bowl Board, the board at Ken Cooper’s Aerobics Center. The Bushes regularly attend Highland Park United Methodist Church with a flank of Secret Service agents-whose presence became necessary after Colombian drug lords threatened the Bush family early in the president’s term.

The Secret Service has become a fixture in the Bush neighborhood, where the family lives in a modest brick house a few blocks from the elementary school. Their neighbors, of whom I am one, have become accustomed to the agents1 idling jeeps and station wagons parked for hours outside the playground or the Bush home. Still, the Bushes seem determined that Barbara and Jenna live as normal a life as possible. Friends describe them as involved parents, down-to-earth, the kind of folks you can drop by to visit or grab a Sunday breakfast with at Roscoe White’s after church.

The first time I met George W. Bush was just before the election in 1988. Mutual friends had given a brunch to introduce the Bushes to the neighborhood. We stood in line together at the buffet and George asked me what I did. When I told him I was with D Magazine, he asked, “What does the D stand for-dumb?”

It was not meant maliciously, and it was typical, say his friends. “He’s one of those people who can call you a -head and you wouldn’t take offense,” says a tennis partner. “George likes to give people a hard time,” says another friend, “but he is so charming that it doesn’t stick.”

He will need his charm to get through this year. With the Rangers in a PR pickle for not having sewn up Sierra, and his father fighting to regain lost popularity ratings, George likely will be crisscrossing the state on behalf of the elder Bush, “letting people smell me,” as he puts it.

That will give him ample opportunity to hone his image as a real Texan before he launches his own campaign. But appearing as just plain folk should come fairly easily. A couple of years ago, this magazine ran a small photograph of George picking his nose while sitting in the stands at a Rangers game-a moment that was captured on national TV. His reaction was telling:”I deserved that,” he said later, laughing. “And really-thanks. Anything you can do to make me more appealing to the common man is much appreciated.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain