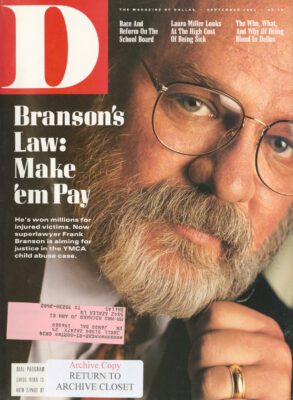

ATTORNEY FRANK Branson asks a lot of questions. Big questions.

What’s the value of a human life? How do you measure what someone might have accomplished if his brain hadn’t been damaged in a car accident? What do you do to compensate a child who’s left blind for life? How much should a hospital pay when a nurse fails to aspirate a woman during delivery, causing her to choke to death on her own vomit?

Over the years, Branson, whose field is the high-stakes arena of personal injury and malpractice, has found answers to these questions for people like Kellie Birchfield, a little girl who was blinded shortly after birth by an oxygen overdose. Jury verdict: $6.3 million; after interest, on appeal: $8.6 million. For the parents whose two boys were thrown from a State Fair ride, leaving one dead and the other seriously injured. Settlement: $10 million. For the family of a victim of the Delta 1141 crash at D/FW airport, who was burned over three-fourths of his body and lived for several days before dying. Settlement: $6 million. In less than three weeks last summer. Branson’s firm settled four pending cases at a million or more each, totaling judgments in the neighborhood of six million.

Working on a contingent basis, as Branson does, he gets nothing if he loses, Victorious, he nets a third or more of each settlement. That translates to the kind of money that enables him to fight huge companies in court, always financing the legal blitzkrieg himself. “I bring the ability to put my clients on an equal footing with their adversaries,” he says. Still, for most Dallasites, the question is: Frank who? Branson isn’t well known outside the ranks of his colleagues, in Texas and beyond, many of whom seek his help on cases they can’t handle. In October 1989, Forbes, ranking him among the 63 top-paid trial lawyers in America, reckoned his annual income at $2.5 million-probably a low-ball figure.

All of which makes his latest case a potentially significant one: Branson is representing the parents of two boys, ages 4 and 9, who were among the 40-plus children who have told police that they were molested by David Wayne Jones, both at the East Dallas YMCA and while he baby-sat for them in their homes. Branson, who filed suit 10 days after Jones was convicted of molesting two other boys, is seeking an unspecified amount of money to compensate the boys and their families for past and future medical expenses. Before he filed suit, Branson dug up a bunch of unpublicized civil suits against the White Rock YMCA from the early Eighties, focusing on a day-care director convicted of other molestations. Branson believes that despite these previous lawsuits-all settled out of court-the Y has done little to change its procedures.

“It’s a frightening picture.” Branson says. “If your organization or mine was not run better, you’d go belly up. It’s hard to imagine that, after the first incidents, they wouldn’t set policies, checks and balances to keep a counselor from being alone with a kid.”

Branson hopes the suit “will get their attention” at the YMCA. It already has his attention. Branson accepts only about one out of 50 cases he’s offered, a figure that shrinks to one out of 80 in medical malpractice cases. When he goes into court, he pours his guts and his wit and his carefully drawled, crafted sentences into proving his client’s case. His dramatic ! presentation of evidence, often through the use of graphic video recreations, is one of his hallmarks. But he also offers juries a compelling story of his client’s life before and after the injuries to his body and spirit.

Now, in the YMCA case, Frank Branson will ask another question: What justice is there for children who’ve fallen prey to a trusted adult’s dark designs?

THE SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS HITS YOU immediately in the reception area of Branson’s mahogany-paneled law offices on the top two floors of Highland Park Place. The Oriental rugs reek of it; the heavy antique tables and desks are steeped in it: it bounces off the tessellated marble floor of the spacious octagonal entry way and emanates from the 18th and 19th century oil paintings of pastoral and hunting scenes. The furniture scattered around the waiting rooms displays a polyglot patrician heritage-English library chairs, French baronial dining chairs, ornately carved Spanish armchairs, a Louis XIV desk, a 17th century hall table.

And everywhere else, there’s green-a deeper shade of money green-carpeting, wall coverings, velvet upholstery, even the thick monogrammed towels in the private restroom.

A client-or potential client-could feel very encouraged walking into all this tasteful splendor. The place speaks of confidence, stability and. yes. scoring big. Conversely, a corporate defendant or an insurance company lawyer might feel a certain tremor of unease at the thought of all the past settlements that have been laid down to finance this princely lair.

Now 46. Branson has seen his girth widen considerably since his high-school football days. His handshake is firm; his hands huge. Shoulder pads would be redundant in his slightly rumpled custom-made suits. Under 5’10″. he radiates power, but it’s a strength that appears totally under control. His old mentor, prominent workers’ compensation attorney John Wilson, talks about that power: “If you feel his arms or his shoulders-or at least the last time I slapped him on the back or grabbed him by the arm, why. he was like rock. And maybe that power-that physical power-gives him the kind of sense of control that he gives off in the courtroom. But he’s a powerful individual in more than just a physical sense.”

When Branson is in a room, everybody knows it. Not because he is loud or abrasive, but because he’s there. Despite his heavily muscled body, he seems to glide across the floor to greet a visitor; his gestures are slow and deliberate. Unlike most people in his high-energy profession who always seem to be strung on a tight bow, Branson is relaxed and gracious. His speaking voice is smooth and low, with just the right tinge of Texas drawl. This is the voice that his former associate Frank Misko says often lulls witnesses to sleep. Us effect is to give people a sense of security. “He makes them think they are dealing with a simple, good ol” boy, when on the contrary, Frank’s questions are very artfully framed, maybe dealing with an extremely technical matter, and he catches people off guard.”

Killer instincts aside, Branson is, by all accounts, a genuinely nice guy. Even though his chosen line of work breeds contempt in the hearts of many-especially among insurance companies and the defendants’ bar-it is virtually impossible to find anybody who won’t sing the praises of Frank Branson. And this isn’t just loyalty of the brotherhood or the code of silence among lawyers. He’s aggressive, say his fellow lawyers, but never arrogant. His friends say he’s loyal to the core. His opponents commend his integrity. Judges he’s appeared before note his thoroughness. His ex-wife. Alice Rogers, now a Dallas family court master, allows that if he has one fault, it may be that he’s too generous.

Parkland Hospital attorney Tom Cox. the natural opponent of a medical negligence trial lawyer, says that lawyers in malpractice often don’t do enough research and come in with half-baked cases. Not Branson. “When Frank takes a case,” Cox says, “you know he has reached a level where he has evaluated the whole thing early on, and basically has a sure thing.” Cox adds that Branson is highly ethical, which he says is not always the case in the liability business. “I’ve talked to people many times, people of questionable ethics who pull dirty, underhanded tricks, but Branson’s strategies are always aboveboard. When he tells you something, you can believe it. In legal circles that’s a pretty valuable commodity.”

Branson’s life has been based on winning from an early age, though it was sports and brains that drove him, not money. From his junior high-school days in White Settlement, he was a ferocious athlete. “Frankie beat the crap out of me on the football field,” remembers Jim Lane, a friend from those days. Branson and Lane, a lawyer now practicing in Fort Worth, later went on to TCU and sowed a few wild oats, tooling around in Branson’s beat-up Corvair. Although they’ve drifted apart professionally (Lane is a criminal defense lawyer), the two men remain friendly competitors. “When he and I are together, no matter what it is. we start betting each other-whether it’s a handball court or a shuffleboard table or anything. Frank’s got to compete; he’s got to go to win. He never backs off.”

Competition is in Branson’s bones and in his genes. His dad was football coach at Brewer High until, in Frank’s first varsity scrimmage, the boy got hit hard from behind. Determined not to show any favoritism, Coach Branson made his son get up, yelling: “Come on, you weren’t hit any harder than a popcorn fart.” Branson struggled up, played through the rest of the scrimmage, ran wind sprints afterwards, and went into the locker room. That’s when Frank realized he couldn’t raise his arms high enough to get off his helmet. A doctor told his dad later that night that Frank’s neck vertebrae were broken; if he’d been hit anywhere sideways during the remainder of that scrimmage, he might have been crippled for life. Stunned, his father quit coaching after that season.

These days. Branson’s opponents are usually lawyers for large companies. Ironically, one of the shaping experiences of Frank Branson’s life was his brief stint moonlighting as an independent insurance adjuster during his last two years in law school. The work paid better than waiting tables at Steak and Ale. which he’d done his first year. Beyond that, he says, adjusting claims and following the claims process opened his eyes to the huge inequities he perceived between the insurance companies and (he claimants. This experience offended his sense of fair play.

“It just wasn’t a level playing field.” says Branson. Big companies could afford to send a team of lawyers in to fight a case. An ordinary person, even a relatively wealthy one. simply couldn’t afford to pay for enough lawyer time. Nor could many lawyers working on a contingent basis afford the investment of time and money, even if they had an ironclad case. “What the insurance companies did was to try to starve out the contingent lawyer, and it was a strategy that worked lime after time,” Branson says. It appeared to him that only someone who had the guts and wherewithal to spend as much as the defense lawyers, and who could marshal the same resources, could get a fair settlement for a victim.

So Branson paid his dues and spent his early career getting to the point where he, as a financially independent lawyer, could go eyeball-to-eyeball with a General Motors, a Delta Airlines, a major hospital. “I only accept cases where I believe the client has been severely injured by a wrong-an injustice,” Branson says. He sees the trial lawyer as “the knight in armor fighting for the justice of his client’s cause.” Or the “watchdog of the system.”

“The only way the big corporations or entities are going to practice safer medicine or change how they do business, or retool a product, is if we get their attention by hitting them where it hurts the most-the bottom line.” Frank Branson hits them harder and more often than most. But it didn’t happen overnight.

AFTER A YEAR OF law practice in Grand Prairie, Branson wanted to hone his trial skills and reckoned that workers” compensation law was the way to go. So in 1970 he sought out the dean of workers’ comp litigation in the Dallas area. John B. Wilson. As it turned out, Wilson got what he still claims was the best student he’d ever had. “He just soaked up everything and I found myself learning from him before very long,” Wilson remembers.

What made Branson so good, says Wilson, was that he really worked at learning. “He always had questions. This is the thing I miss in most young people who work here now- they’re afraid to come in and ask questions. Frank was always asking questions,”They would also sit around the firm’s law library until midnight and beyond, looking up the case law. figuring out strategies for presenting the facts of their case, and anticipating where the ax might fall in a trial. It was here that he learned to devote himself to the sort of dogged preparation that has become a Branson trademark.

Branson honed his courtroom style by trying 15 to 20 cases a year, In 1975, having made full partner in just five years. Branson tried the case with which he is most pleased with the results. It was a malpractice issue- the blind baby case, Kellie Birchfield-in which he fought Wadley Hospital in Tex-arkana and received one of his first million-plus judgments-$6.3 million, upheld on appeal with interest tacked on.

It was the biggest prize ever for Wilson’s firm and led, by 1977, to what both men describe as a friendly parting of the ways. Branson, after winning so big for the Tex-arkana child, wanted to expand his practice considerably beyond the confines of workers’ comp. He asked Wilson to come along with him, but the older lawyer politely declined. “I saw Frank as somebody who was going to be a big case lawyer and I’ve got a little ego. loo,” Wilson says. “I didn’t want to end up being the tail the dog was wagging.”

FRANK BRANSON WONT TAKE ON ANY case that he doesn’t believe in strongly, even for friends, Often he’ll spend tens of thousands of dollars before he even accepts a case in order to check out its merits and to determine that the case can be won.

Once Branson’s on a case, though, he’s a man possessed. He may spend hundreds of thousands more building his case. Assembling expert witnesses. Pulling together medical evidence and gathering records. Creating a graphic set of evidence, using pictures, testaments, computer graphics, medical illustralions, and resumes enumerating the impressive credentials of the experts he will bring to the courtroom. Doing whatever it takes to put together a finished, bound document known as the “settlement brochure,” the plaintiffs equivalent of the “or else” threat. It is the evidence tool that presents the facts of the case as they will be delivered in the courtroom-sometimes with a smoking gun or two deliberately left out.

Branson is recognized as a pioneer in the development and effective use of new techniques of demonstrative evidence-and video is a prime example. Although Branson is not the only trial lawyer to use such graphic paraphernalia, he has raised the practice of audio-visual demonstrative evidence to a new plane. Not only does he videotape all his depositions for possible use as settlement bait or actual trial evidence, but he produces elaborate, vivid (and sometimes gory) reenactments of the accidents his clients have suffered. He may hire Hollywood stunt crews to stage some of this.

In his own offices, he has a full-time staff of audio-visual experts including an ex-TV news editor and two artists with graduate degrees from Johns Hopkins University in the highly specialized field of medical illustration. They can create computer simulations, photo montages, color illustrations of all sorts, and convincing anatomical models-in one case, a lifelike mold of the head of a client whose brain injury was not apparent from looking at him. The skull was hinged to open, revealing a reproduction of the brain with a piece of bone embedded behind the victim’s eye socket.

In addition to the nine lawyers who are associates in Branson’s firm, including his wife. Debbie, his support staff includes three full-time nurses, an insurance claims consultant, and two investigators, one of whom is Branson’s younger brother. The office is equipped with state-of-the-art computers, a full graphics depart-ment, slide-making equipment, and a sophisticated video production studio. There are dropdown screens in Branson’s private office and in the conference areas. A hidden switch activates the video screen, which rolls down slowly from the ceiling while the heavy curtains glide shut around the room, closing out the expansive views of downtown Dallas and creating a darkened hush.

Viewers might see a grisly reenactment of a car fire in downtown Dallas, in which the victim-engulfed in flames from the sudden explosion of the compressed gas cylinder he was delivering-is trapped in his car because his seatbelt fused from the heat. Or the audience-often insurance lawyers-might be treated to 15 minutes of devastating deposition from a doctor involved in a wrongful death case, who admits on camera to having been suspended from one hospital for fondling female patients and from another for drinking on post-op rounds and serving alcohol to patients” visiting families. Then, in a blackly comic sequence, the good doctor, responding to gentle but persistent off-camera questions from Branson about medications he might be taking, starts pulling pill packets and vials of stuff out of his pockets, one at a time, producing enough pharmacological power to knock out a horse.

This eye-catching display-which one judge aptly dubs “Branson’s Star Wars stuff-is designed for courtroom use. But such damaging “demonstrative” evidence often makes defense lawyers want to settle rather than face almost certain defeat in the courtroom. Whereas Branson used to try 15 or 20 cases a year, now he seldom takes more than two a year to the courtroom stage. Says another Dallas judge: “If 1 were a defense lawyer going in to his offices and he sat me down at that conference table, I know he would intimidate the hell out of me.”

Although there is no such thing as a “typical” case, a close examination of one of Branson’s personal injury trials demonstrates his legal style from start to finish- and gives clues as to how he’s likely to approach the impending YMCA suit.

The case of Larson v. Clayton-Mayes Co.. Inc., began one hot August afternoon in 1982. Pete and Robyn Larson and their two kids were driving east on 1-20, headed for a family outing in their white Dodge camper, when their lives were changed forever. An 18-wheeler, cruising along the flat stretch of highway at a high rate of speed, pulled out into the left lane and started to pass them. Suddenly the truck, loaded with frozen foods and weighing 65,000 pounds, drifted back toward the right lane and slammed against the left rear of the Larsons’ RV. The camper left the road and rolled over at least three times, parts flying in all directions as it virtually disintegrated.

The occupants were flung out of the vehicle. The children were not seriously hurt, but Robyn suffered multiple internal injuries and a compression fracture of the spine. Today, she lives with decreased mobility and constant pain. Pete fared much worse: His spinal cord was severed, leaving him a paraplegic.

The Larsons initially hired a Tyler attorney who soon realized that the case was too much for him to handle alone. The attorney brought the case to Branson, who, armed chiefly with the police report, look the case. The driver. Rickey Lee Brown, claimed he had been leaning down to pick up a lit cigarette he had dropped when the accident occurred. He was cited for speeding and negligent driving. The (ruck was owned by a California-based trucking company whose insurance coverage, between its primary and excess carriers (the second layer of coverage carried by many large corporations), totaled about $3 million.

The accident report, in addition to the Larsons’ obvious injuries, probably would have been all the evidence gathered by some trial lawyers. There were witnesses who’d seen the accident. There were the doctors and rehab specialists to call on. There was the highway patrolman at the scene who took the initial statements. And, of course, there was Pete Larson in his wheelchair, firsthand testament to a fundamentally diminished life. But the Branson machine ground into action to go well beyond that. In all, approximately two years would be devoted to preparing the case.

First, his staff investigators rooted out the fact that the driver had a horrendous driving record, having been cited for speeding three times since the accident and tagged with numerous violations before that. They also found he had spent time in the Louisiana state penitentiary for multiple counts of forgery-a point that proved useful when Branson had the driver brought to Dallas for video deposition.

Branson starts his questioning of Brown by reminding him that he’s under oath and could be sent to prison for lying. Then, in a gentle drawl, he slips in the knife: “When was the last time you were in prison?”

Brown, who is obviously ready to tell his reaching-for-a-cigarette story one more time, is thrown for a loop and stutters back: “I don’t rightly know, sir.” But he doesn’t deny it. After further low-key questioning, Brown admits that he’s been in prison for forgery. Branson’s line of questioning has completely flustered the man-as it was intended to-and he needs only a few more minutes to get what he’s really looking for: an admission that the driver was asleep when he hit the Larsons. Branson today still marvels at that dramatic confession, as if he had nothing to do with it. “I just had a hunch that he’d fallen asleep but I didn’t really expect him to admit as much.1”

With Brown’s damning half-hour on tape, the Branson machine keeps rolling. His investigators get a list of all ex-employees from the California-based trucking company. Among them, they find another smoking gun: a fellow driver of Brown’s who has quit the company and is willing to testify that Clayton-Mayes ignored the statutory rules on sleep allowances for interstate truck drivers, forcing him to drive shifts that pushed him beyond his endurance.

All the expected witnesses are deposed and prepared for possible trial appearance. Expert witnesses are called in and videotaped. Some will appear in person at the trial, but parts of their testimony will also be used in the pretrial video “brochure.” There’s the man who says he saw Brown get out of his truck and immediately light up a cigarette, making no attempt to go back the 500 yards or so and see what has happened to the people in the camper. The witness says Brown seemed vague and confused, “as if he hadn’t had enough sleep or something.” There’s testimony from Pete Larson’s boss on his excellent career record and his potential as a top manager in the retail chain. There are the doctors at the hospital who describe the victims’ injuries in excruciating detail. And there’s another eyewitness who works with Branson’s sophisticated art staff to help create a model of the accident scene, which is then animated for use as a graphic visual tool with a soundtrack in which that witness describes what she saw happening. The art staff, working with medical expert witnesses, also creates elaborate illustrations of the victims’ injuries.

All this, along with an economic projection of Pete Larson’s “lost earnings” and estimates of the Larsons’ lifetime medical costs, is gathered and neatly indexed in a leather-bound spiral notebook, embossed with the name of the case. It’s official: the settlement “brochure.” Then Branson stands in front of a videocam in his office, firing the opening salvos on behalf of the Larsons to his unseen audience-in this case the lawyers and claims adjusters for the defense. He is essentially delivering the guts of the arguments he will bring to the courtroom, should the case come to (rial. His video crew then edits the video testimony that will go onto the tape, and the whole is rolled into a 54-minute “video brochure.”

A few days later, the defense is presented with this powerful ammunition; Branson demands as a settlement the whole $3 million for which Clayton-Mayes is covered. He gives them 30 days to respond. Two days after his time limit, the defense answers with an offer of about $1 million. Branson knows that the primary insurance carrier is covering just that amount, so he figures that the excess carriers have refused to put anything on the table. He and his clients have already agreed that they should go for the full S3 million. Branson refuses the offer, shuts the negotiating window, and requests a trial setting.

Shortly before the trial begins. Branson holes up at his Van Zandt County ranch and goes into crash preparation mode. He pours over the reams of evidence, formulates his opening argument, cements over any possible holes, puts his witnesses in strategic order. He has his ace in the hole, the ex-employee (who was not on the video brochure). but he’s leaving nothing to chance.

On the court date, the two sides meet before a federal judge in the stately old Tyler courthouse to set their case in motion. They’ve drawn a veteran, no-nonsense judge. Branson would like at least a week to try this case, but the judge wants the whole affair settled in three days. There’s no time to waste: this is a trial in fast forward.

Branson has two main tasks: First, he needs to show the jury that his client, a strong family man with a good work ethic and high potential as a well-paid manager. has been irreparably damaged, physically and financially. That will demonstrate the need for actual damages to be paid. The second task is to prove that the trucking company’s management was negligent, enforcing unsafe schedules for its drivers. That will lay the groundwork for exemplary damages.

The general rule is to introduce the strongest evidence as early as possible. In this case, (he videotape of the driver’s “confession” is so damning there’s no question it is the first thing presented to the jury. In fact, Rickey Lee Brown himself never shows up at the trial. Branson certainly isn’t going to subpoena him-he has just what he needs, already on tape. The only witness the defense produces is the president of Clayton-Mayes. who denies all culpability. On rebuttal, Branson produces his smoking gun, the ex-driver, who elaborates on the company’s unsafe driver practices. The fact that the fellow has only one eye- -and had only one when he was driving for Clayton-Mayes-does not help the company’s defense.

Branson, with the help of his graphics and the animation of the accident narrated by the eyewitness, puts the witnesses through their paces as fast as possible. He doesn’t push. It is a supreme effort of will to appear calm; to look as if he’s got all the time in the world to spend telling the jury his client’s story, all the while keeping a careful eye on his vanishing time.

Pete Larson sits in his wheelchair at the counsel’s table next to Branson and his associate. Paul Gold. Branson has taken a calculated risk in having his client there throughout the trial. In a long trial, juries tend to get desensitized to the everyday attendance of a visibly injured or handicapped plaintiff, and may even resent his presence. But Branson figures this trial is going fast enough for Larson’s presence, in addition to his brief but articulate appearance on the witness stand, to act in his favor.

About a day and a half into the trial, Branson gets word that the excess insurance carriers, who didn’t even show up for the initial settlement conference, have arrived at the courthouse ready to put their money on the table. Branson is on a roll, preparing another witness, and avoids them. During the lunch break, the judge calls Branson into his chambers. There sit the claims representatives for the carriers and the two lawyers for the defense.

The judge, who clearly wants to move things along, puts Branson on the spot. “Mr. Branson, the excess carriers here want to talk settlement.”

Branson has no desire to alienate the judge. But he believes the jury will award his client well above the $3 million. If he’s wrong, of course, he could wind up losing thousands, even millions.

Branson responds: “Your Honor, four months ago now. I spent a lot of money on behalf of my client putting together a video settlement brochure so as to avoid this court having to go through a part of a trial, waste its time, and then stop and talk settlement. I gave the defendant a number that my client would accept, which was the amount of their policy coverage. They didn’t even give me the courtesy of responding to my demand within my time limit, and then they only offered the primary one million dollars. I therefore did not counter-offer. They knew my bottom line before. I have already talked settlement with them. I talked to my client and we have now taken up a day and a half of this court’s valuable time, your Honor. and we would like a jury verdict.”

Less than a day and a half later, he gets it. The jury returns from brief deliberations to find for the plaintiff: $2.7 million in actual damages: $2.8 in exemplary (punitive) damages. It was the largest jury award in Smith County history. It was also the first time this federal judge had allowed Branson’s kind of visual evidence in his courtroom.

WITH BRANSON’S SUCCESS HAVE COME some new tastes and the leisure to savor them. He has a special fondness for malt scotch and the bar in his office is stocked with a vast array of the best Scotland has to offer, from Glen Livet to Sheepdip. He’s recently taken the time to read for pleasure and is crazy about historical biographies. He owns one of the few original copies of Ulysses S. Grant’s autobiography. He’s become an avid collector of Americana. European antiques, and weaponry. Bat Mas-terson’s gold-knobbed cane and his pistol hang in a glass case in his office bar. So does one of John Wayne’s guns. The conference rooms are filled with Civil War rifles, an 1812 musket, and assorted old pieces.

The personal trappings that Frank Branson’s victories have afforded him are all there, Texas-style. The rambling Tudor house on Turtle Creek. His and hers Mercedes roadsters. The Rolex watch. The diamonds. The custom-made suits. The sprawling East Texas ranch. The driver and the stretch limos. The King Air turbo prop.

You won’t see Branson’s name pop up in the Dallas gossip columns or on the score cards of the charity ball leagues. But Frank and Debbie, although very private about their political and charitable activities, contribute time and money to a number of causes. Like many trial lawyers, he’s a heavy donor to Texas judicial candidates. He’s a longtime Democrat-Governor Ann Richards has visited his ranch for hunting-but he’ll cross party lines to help Republicans he admires.

The Bransons have opened their home to charity events, but don’t seek publicity about [hem. Just last month, at the request of the top organizers of Dallas’s Desert Storm celebration, the Bransons held an elegant Sunday reception for the military brass and assembled dignitaries from the countries involved. The guest list, in addition to assorted generals, included H. Ross Perot. Herb Kelleher. and George W. Bush Jr.

Still, those who know Branson best say he has never forgotten his roots. He can talk to a jury in rural East Texas in simple, direct language, just as he can argue fine points of the law for hours with fellow members of the Texas Supreme Court Advisory Committee or as chair of the Slate Bar Rules of Evidence Committee. He can discuss the earthy realities of artificially inseminating his brood cows from champion Hereford stock, and then shift to a high philosophical plane, bemoaning the terrible wrongs he believes were done to his clients because of some “egregious corporate greed or negligence,” and how, because of that, “somehow, the homeostasis of the world has been put out of balance.”

“I think you train for jury arguments all your life,” Branson says. “You hear phrases that catch your attention coming from all walks of life. I may use a phrase I heard for the first time on the football field, or I might pick up something I just heard in a cocktail conversation that just seems appropriate for the facts. Something that will help the jury understand a complicated issue in some simple way.”

As the YMCA case moves slowly toward the courtroom-Branson considers a December court date “unrealistic’1-he is aware of an irony: The YMCA is not a giant corporation or a big insurance company; it’s a non-profit organization with a usually wholesome image. Could the crusader for the “little guy” be seen as a high-tech, highly paid ogre come to spoil the party?

“I’ve contributed to Y projects over the years.” Branson says. “My son played Y ball one summer. I’m not anti-Y in any way. But what I sec is horrifying from a parent’s standpoint, setting aside the lawyer role for a moment. If what I thought I was contributing to is not better supervised than what I’ve seen in the media lately, I’m very surprised.

“The facts will paint the picture,” he goeson. “I do know there are some terriblyinjured kids and parents now. Maybe theY will show that Jones misrepresented thefacts in his statement and that none of thisever happened. Nobody would be happierthan me and these parents if that were thecase.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Preview: How the Death of Its Subject Caused a Dallas Documentary to Shift Gears

Michael Rowley’s Racing Mister Fahrenheit, about the late Dallas businessman Bobby Haas, will premiere during the eight-day Dallas International Film Festival.

By Todd Jorgenson

Commercial Real Estate

What’s Behind DFW’s Outpatient Building Squeeze?

High costs and high demand have tenants looking in increasingly creative places.

By Will Maddox

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 2

It's time to start worrying.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo