THE AGITATED CALLER IDENTIFIED HIMSELF AS AN ATTORNEY AND ASKED THE WAXAHACHIE POLICE DEPARTMENT TO send a squad car ASAP. A man who was drunk or crazy or something was creating a ruckus, beating on his door and shouting obscenities. ●The cops sped through the gentrified sections of Waxahachie, where affluent professionals have made elegant offices out of the old Victorian houses that line the streets of this town 30 miles south of Dallas. Across from the house on North College Street, they found a peculiar sight. On that hot August morning, no one was pounding on anyone’s doors or windows, but a man had parked his car on the side of the road. A huge sign was draped over the car: “Ask me about James Hanners, Atty.” ●They watched as 44-year-old James Kozacki, the owner of the car, talked to the curious who stopped to ask what was going on. Hanners, the man named on the sign, wanted Kozacki to desist or face the slammer-but police told Hanners that Kozacki was on public property and was exercising his right to free speech. There’s no law against lawyer-bashing. ● Kozacki. an unemployed salesman and laborer, worked his anti-lawyer gig like ajob: He parked across from Hanners’s place for five days, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.. talking to those who stopped, giving out his phone number, gathering others’ addresses, and becoming the talk of the town. His approach was unorthodox, but he was at his wits’end. ● Kozacki had hired Hanners, a sleek 37-year-old who had practiced law in Ellis County for several years, to handle an out-of-court personal injury case. Then things turned sour. Kozacki says that Hanners refused to give him $9,800 of the settlement, which he had hoped to use to start a business. And Kozacki went ballistic when Hanners had the gall to send him a final bill for $2,000. After weeks of arguing with Hanners, Kozacki stopped talking and started protesting.

“I couldn’t get his attention any other way,” Kozacki says. “Besides that, everybody else had to know about him.”

Once they heard Kozacki’s story, those who stopped commiserated with him. In fact, many cheered him on. Go, Kozacki! Because while many of them had never heard of the attorney named on the sign. Kozacki’s roadside revenge let them give vent to their own feelings about lawyers, about the hated scourge of legal locusts plaguing the land and infesting their lives with double talk, obscene bills, and incomprehensible documents in triplicate.

Everyone gripes and complains about lawyers, but most simply accept them as an unpleasant fact of life, like hemorrhoids. Not Kozacki. He was Peter Finch in the movie Network, urging viewers to go to their windows and scream, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not gonna take it anymore!”

As it turned out, some of those who stopped had indeed heard of the aforementioned lawyer. And they had their own horror stories about him. So, encouraged, Kozacki decided to escalate his peculiar protest. He put an ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light: “Attention! If you have had or are now having a problem with James Hanners, Attorney. .. Please call.. ” and gave his phone number. Astounded by the response, he told callers he was holding a town meeting at the chamber of commerce offices.

That night, more than 20 people showed up. Without mentioning Hanners’s name-in order to avoid a slander suit, he says- Kozacki handed out the proper papers and explained to his new compadres how to file a grievance against an attorney with the State Bar of Texas.

Then, after the town meeting, Hanners struck back. On September 16, Kozacki was arrested by two DeSoto police officers and jailed in Dallas County on charges of engaging in organized crime. Hanners claims that Kozacki hired two men and a teenager to burglarize his apartment in DeSoto; one of the men was stabbed repeatedly by Hanners, who held him at gunpoint until police arrived.

Kozacki, who says he was framed, could become a martyr to the cause of lawyer-bashing. If he is convicted in a Dallas County courtroom (he goes on trial this month), the combative protester faces a jail term of five to 99 years-all for doing what thousands have dreamed of doing: getting even with a lawyer.

SHAKESPEARE SAID IT BEST IN Henry VI: “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” Never mind the quote’s context-it’s the sentiment that’s survived, and for very good reason. Throughout the centuries, since laws became so complicated that people had to hire experts trained by John Houseman-look-alikes to help them wade through the morass of whereases and hereinafters, people have loved to hate lawyers.

For a long time, our natural abhorrence of attorneys was tempered somewhat by those images of lawyers who stood for noble, high-minded causes. After all, Abraham Lincoln was an attorney. So was Clarence Darrow. In popular culture, we had Atticus Finch, Gregory Peck’s patrician attorney in To Kill a Mockingbird. And on television there was Perry Mason, the portly professional who always defended the falsely accused, invariably exposing the real killer on the stand during cross-examination.

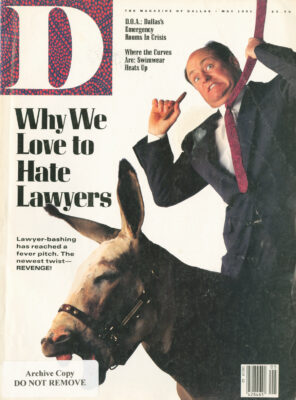

Now, due to numerous insidious factors, those courtly, compassionate images have been eaten away by the sulfuric acid of greed and polysyllabic patronizing. So lawyer-bashing has reached a fever pitch in the Nineties. It’s the favored cocktail party game. New books out include the illustrated What to Do with a Dead Lawyer, a joke book called Skid Marks (“What’s the difference between a dead skunk and a dead lawyer? Skid marks in front of the skunk.”), and 29 Reasons Not to Go to Law School, written by two dropouts from the legal profession. Presidential spokesman Martin Fitzwater even got into the act last year when he opined: “Lawyers certainly deserve all the criticism they can get. Everyone ought to take the opportunity to blast lawyers.” When even government bureaucrats feel safe in taking shots at lawyers, you know things are getting bad.

Lawyers are definitely feeling the soaring animosity. In an effort to counter the negative climate, the State Bar of Texas initiated a series of allegedly humorous radio spots about the legal system by that robed funnyman himself, Dallas Federal Judge Jerry Buchmeyer, While the public response to the spots has been highly positive, Buchmeyer says he has gotten complaints from attorneys who feel the spots are beneath lawyers’ dignity. Wherever that is.

Come on. It’s hard to see how the public’s image of lawyers could get much worse. Courtesy of Buchmeyer: What’s black and brown and looks good on a lawyer? A Do-berman. What do you get when you cross the Godfather with a lawyer? An offer you can’t understand. How can you tell when lawyers are lying? Easy. Their lips are moving.

A recent survey conducted by the Wash-ingtonian magazine showed that the public rates lawyers far down on the scale of trustworthiness, even below the media. In a world with Geraldo Rivera and the Pentagon press corps, this should serve to scare bar associations to death.

Maybe the rising tide of enmity toward attorneys is a result of the change in our images of those who are supposedly dedicated to pursuing justice through law. Richard (“I Am Not A Crook”) Nixon is an attorney, as was the slimy Roy Cohn. Naturally, television attorneys have sleazed downward to reflect reality. Instead of Perry Mason, we’ve got Arnie Becker, the silken, womanizing, duplicitous. anything~for-a-price sharpie on LA. Law.

In their feeding frenzy, lawyers have overreached themselves while reaching for our wallets. Consider, for example, the ruling by the Supreme Court {another group of lawyers) that allowed the breed to advertise right along with the laxative hucksters and the late-night hawkers of Have a Nice Day: The Super Hits of the Seventies. The message is clear: Forget dignity. Forget decorum. You might be hurt even if you feel great. Give us a call.

And then there is the problem of sheer numbers. It seems anywhere you swing an arm these days, you whack an attorney. The United States has 1.3 million lawyers, or one for every 192 men. women, and children. (Yes, children need lawyers these days to sue their parents,) That’s five times as many lawyers per capita as in West Germany. Dallas County alone has at least 10,000 practitioners of the law.

Yet, like rabbits, lawyers continue to breed at an alarming pace. This year, some 50,000 fledgling attorneys will graduate from law schools across the country. And students continue to pound on the doors of law schools begging to get in. In 1984, there were 172 accredited law schools in America; by 1990 there were 205.

Are they going out to join the Peace Corps, bringing desperately needed restraining orders and writs of mandamus to under-lawyered Third World countries? Will they file class action suits against the Saudi government for denying women the right to drive? No! They’ll open offices in glitzy skyscrapers in downtown U.S.A., preferably with lots of marble and incomprehensible art that can be charged to clients as “overhead.”

That brings up another infuriating fact of life in lawyer-land. Fees. Outrageous fees. Lawyers in Dallas routinely charge $200 an hour: a survey by the State Bar of Texas found that one Dallas firm charges as much as $350 an hour for some work. (You can bet those same lawyers would scream bloody murder if their plumber charged $350 an hour-though of course those plumbers never sat in lecture halls pondering the seminal importance of Raccoon Lodge No. 360 vs. Kramden et a/., op. cit.. passim, 1956, so of course they make less money.)

High overhead and escalating salaries put lawyers under pressure to bill ever-increasing numbers of hours. Some East and West Coast firms now expect their attorneys to bill 2,200 hours per year, and that attitude is creeping into Dallas firms. How do you bill that many hours? Very creatively, because that comes out to billing seven hours a day, six days a week. 52 weeks a year. No vacations. No two-hour lunches. No time to read and keep up with recent revisions in the Maritime Extension Act of 1934. No time even to go to the bathroom.

At many Dallas firms, where starting salaries have soared to $60,000 or $70,000 (just take a deep breath and keep reading), there’s pressure to bill at least 50 hours per week. “You really have only 30 billable hours, not counting lunch, etc.,” says one lawyer, who maintains a solo practice to avoid the billing blitz. But even second-rate attorneys who can handle the pressure can make well over $100,000 annually; in some fields, such as bankruptcy and family law, lawyers can make $500,000 and up.

Many clients are beginning to get the sneaking suspicion that their bills might be a tad, shall we say, unrealistic, They’ve heard the horror stories. Like the one about the client whose attorney billed him for 86 hours of his time-on one day. Or the auditing firm who discovered lawyers who had billed $30,000 for drafting briefs only several pages long. Or the story about the widow of a lawyer whose partners promised to handle everything after his death. Don’t you worry, little lady. She later discovered they had billed her husband’s estate for the time they spent at his funeral.

It’s as if, somehow, lawyers’ time-even off the job-is worth more than the average mortal’s because they managed to survive three years of excruciatingly boring classes and learned to throw around some intimidating Latin phrases. A maddening example of this superhuman arrogance can be found in the case of one Robert Nathan Goldstein, a hot-off-the-presses prosecutor in the Dallas district attorney’s office, who got himself in hot water by trying to find someone, anyone who would pay for his time.

Goldstein, it seems, was in need of some repairs in his University Park condominium. Apparently he realized that the fix-up would require that he make some sort of effort to hire a workman and supervise the process. Perhaps he was training to go into private practice. Whatever the reason, Goldstein couldn’t allow those precious minutes spent on his own private business to go unbilled. So he submitted inflated bids to his insurance company.

“Shit, I’m a f-ing lawyer,” the smarmy Goldstein was taped as saying, courtesy of a hidden microphone worn by an (honest) contractor who tipped the police, “I want to be paid for my goddamn time.”

Despite the fact {or maybe because of the fact) that six lawyers-including Goldstein-handled his defense, he was convicted by a jury of his peers. The verdict is on appeal.

The pressure for billable hours manifests itself in myriad small but expensive ways. At many area firms, lawyers are required to bill a minimum of two-tenths of an hour (12 minutes) for taking a phone call, even if it lasts 30 seconds. At $200 an hour, that call will cost a client $40. It’s three-tenths of an hour, or 60 bucks, if the attorney is the one placing the call-for all that extra time it takes to dial, you know.

The naked greed that has reared its head at some big area firms can be attributed at least in part to the rampant “eat-what-you-kill” philosophy. That means that the lawyer who brings in the client’s business-whether that lawyer handles the legal work or not- gets the credit when it comes time to divvy up the spoils. Clients may not realize that “their” lawyer is not the one who really slaves over their motions for summary judgment. That’s often farmed out to junior associates, while “their” lawyer goes prowling for more business.

HISTORIANS OF THE 21ST CEN-tury, puzzling over the dizzying decline of what had been the robust American empire, may find an answer to the most vexing question of them all: If there are so damn many lawyers, why do their rates keep going up? They may find that lawyers, perhaps by filing an injunction in federal court, were able to have the basic laws of supply and demand declared unconstitutional. When it comes to lawyers, the more of them there are, the more everybody pays. And pays.

Though legal services actually produce nothing, their cost accounts for 2 percent of the United States gross national product. A professor at the University of Texas has estimated that each lawyer in the country costs the economy $1 million each year in lost productivity due to, among other things, time and money wasted fighting spurious lawsuits, and costs added to products due to fear of liability. (The average drug addict costs the U.S. only $200,000 per year.)

Maybe the rates keep going up because unlike plumbers-after all, there are only so many pipes and potties to go around- lawyers can actually manufacture business (i.e., discontent, trouble, and paperwork) where there is none. Filings in state courts have increased five to seven times faster than the population, according to former Colorado Gov. Richard Lamm in his grimly prophetic book Megatraumas. Federal appellate courts alone hear one million cases a year. America has 30 times as many malpractice claims and 100 times as many products claims as British courts.

And often the lawsuits seem so bizarre, so pointless, so infuriating. For example, a Miami woman was awarded $200,000 by a jury after her pet poodle, Klouseaux. was burned by a hair dryer at the Doggie Den, a grooming salon. And legal entanglements killed two of the best things about the State Fair of Texas: the Fletcher’s Corny Dog (robbed of its name because of pending litigation) and The Comet roller coaster (dumped in the trash bin of history partly because of impossibly high insurance premiums). When the public hears of these things, they think of those “Rottweilers in three-piece suits,” as the profession was recently labeled by the prestigious journal Policy Review. Though maybe that’s a bit hard on the Rottweilers.

Perhaps it all started with Ralph Nader, a man who’s been called the patron saint of contingency fee lawyers, when he sued America’s automakers on behalf of consumers to get rid of dangerous idiocies like the Chevy Corvair. For that, the country owes Nader a debt of gratitude. But Nader also helped create a legal climate that in effect banished the notion of bad luck and set up this ruling ethic: Whenever things are unfair, whenever disaster happens, whenever someone slips on the banana peel of life, someone is always to blame. The fatter the wallets, the better. (See “The Case of the Killer TV” in the February 1991 issue of D.)

A billboard near Parkland Memorial Hospital sums up the new attitude: “Injured? Sue the Bums!” On TV at 3 a.m.: “Back hurt? Maybe you’ve been injured on the job.” Or maybe not. No matter. We’ll find someone to pay.

The old art of ambulance-chasing has become blatant gold digging. Attorneys swarm, as in a Biblical plague, to the site of horrific accidents such as the 1989 school bus crash in South Texas, in which 21 children were killed and 60 injured. An emergency doctor who treated victims of that crash says that after all the legal claims were settled, the lawyers made an average of $2 million per victim. The physicians were paid an average of $2 for each child they treated.

Of course it’s vital to protect the rights of people who wake up from an operation to find themselves serving as the home of a misplaced sponge. But in attempting to find someone, anyone, to pay for a tragedy, attorneys file lawsuits that scale ever-greater heights of absurdity.

After the Dupont Plaza hotel blaze, which was set by arsonists, lawyers filed suit against all the manufacturers of flammable products in the building, contending that the carpets and wallcoverings contributed to the smoke and fire. Not content to leave any possible source of income out, they even sued the makers of the dice used in the casino. Last year, a passer-by who rescued several people from the wreckage of a car just moments before it was hit by another vehicle was sued by a survivor whom he didn’t have time to help. The good Samaritan, the lawyer claimed, should have first put up warning devices indicating that the car was blocking the road.

Some of those suits should never make it past the courthouse door. Often the only ones who win are the lawyers. But with increasing competition, more and more attorneys are telling people what they want to hear, rather than what they need to know, especially in cases in which they charge by the hour.

Ronald Wells, a Dallas criminal defense attorney, says he tries to be realistic about clients’ chances of proving their innocence in a criminal trial. And those clients sometimes take their business elsewhere, to an attorney with a more, uh, positive approach. Mark Hasse, a chief felony prosecutor now in private practice, agrees: “The search for fees has become cutthroat. Some lawyers will say anything in order to get a fee.”

But America’s legal system is built on the premise that everyone deserves access to the courts to press their claims. Thus the rise of contingency fees, whereby low-income people can have their day in court without having to hock the farm in advance. If the case is successful, the lawyer takes one-third of the judgment. Even that long-standing policy is changing, as greedy attorneys demand 40 and even as much as 50 percent of any money recovered-meaning that many people will not get the compensation they are entitled to. Some critics charge that such arrangements are really price-fixing. But lawyers have resisted all efforts to limit contingency fees.

Who ultimately pays? Insurance companies, certainly. And who pays insurance premiums? We do. More than 30 percent of the cost of a ladder is due to insurance costs, according to the book Liability: The Legal Revolution and its Consequences by Peter Huber. What Huber calls a “tort liability tax” accounts for one-third of the price of a small airplane and 95 percent of the price of children’s vaccines. Insurance protection. Huber says, adds more to the price of a football helmet than the actual cost of making it.

Contingency agreements, of course, are voluntary business agreements that are built on the lawyer’s expertise and the plaintiffs whiplash. But not everyone sucked into the system volunteers. The next-door neighbor falls on your sidewalk. His kid falls off your swing set. His dog eats your garbage and ends up at the vet. Taking advantage of a con-tingency fee arrangement, he sues.

And-even if you did nothing wrong- you’re stuck with a lawyer’s bill.

Maybe the real reason we love to hate attorneys is that no matter how good we are, how clean we keep our noses, once a legal problem crops up, there’s nothing we can do except hire a lawyer, Judges-lawyers, remember-look askance at people, no matter how intelligent, representing themselves. Such upstarts are not members of the club. They don’t know the arcane rules-and the rules are so complicated, and the documents so obfuscating (a great lawyers’ word) that, well, you have to go to law school to understand them.

Thrust into the legal piranha tank, the average person is helpless, totally dependent on the mumbo jumbo of hired experts. Before a case ever gets near the courtroom, you have to find a lawyer. Catch-22: You have to know a lot of things only lawyers know before you can even make an intelligent choice of a lawyer, and of course you don’t know any of that. Finding a good attorney who will return phone calls, keep the client informed, submit fair bills, and also perform quality legal work can be like shooting ducks blindfolded while wearing a straitjacket. Often, clients don’t know how good their attorney is until it’s too late. They don’t know whether their attorney should have filed 20 pretrial motions or two. objected more or less. And after it’s done, there’s little recourse. Except to hire another lawyer.

Piling horror on horror, there’s good reason to believe that unethical practices by attorneys are on the increase. Funds set up by bar associations to reimburse clients bilked by their attorneys are facing unprecedented losses. The New York bar paid out $4.35 million in fiscal 1990, up dramatically from the $1.9 million disbursed in 1987. In 1990, claims on the Texas State Bar Client Security Fund more than doubled. In December alone, $41,750 was disbursed to 19 clients of one attorney. Can you take a little more? Some studies estimate that as many as 30 percent of all lawyers may have drug or alcohol problems. So you’re not just dealing with Bickel & Brewer or Dewey Cheatham and Howe; you’ve also got Johnny Walker and Jack Daniels on your case.

Is there any road through the labyrinth of lawyerdom? Board certification, a stamp of approval showing that an attorney has handled a certain number of trials in his specialty, is some indication of competence, But it’s not ironclad. A personal injury attorney may have gone to trial 10 times and lost every time, but he’s eligible to be board-certified. How about a famous name? In today’s mercenary marketplace, name recognition can mean the attorney has a good public relations firm rather than a brilliant legal mind. “I’ve tried some big-name lawyers who were buffoons and some no-name lawyers who were great,” says Hasse, who made a name for himself at the DA’s office by winning all but one of his 3,000 felony cases. “Big fees are not a sin if they’re worth it.”

Unfortunately, neither a wall full of degrees nor a full-page ad in the Yellow Pages nor write-ups in the press can protect you from simple sleaziness. Hasse describes a case he prosecuted: A two-time loser accused of cocaine possession was facing a minimum sentence of 25 years. The evidence against him was solid. His court-appointed attorney recommended the defendant plead guilty and take the sentence. Shortly before the trial started, however, another criminal attorney announced he had been hired by the man’s parents to take the case; in return, the couple had signed over their home to the lawyer on the guarantee that the son would get five years.

The lawyer negotiated with Hasse for the five years. Hasse refused. The guy came back-c’mon, as a friend, give him 10? How about 15? Nope, Hasse said; 25 years was the minimum. The attorney finally agreed. His client would accept the 25, the same agreement the free public defender had recommended earlier that morning.

The hired gun worked all of 90 minutes.

He kept the parents’ house.

But he did allow them to buy it back on a lease-purchase plan. Who says attorneys don’t have hearts?

NIGHTMARE STORIES LIKE these infuriate the public, and there’s increasing evidence that consumers are fighting back. Some want simple revenge, like the man arrested in California for buying grenades to get back at his ex-wife’s attorney.

Others, thankfully, are taking a less violent approach through politics, publishing, and picketing. Last year, a Dallas roofer named Alfred Adask ran for the state legislature on an anti-lawyer platform. His most generous assessment of lawyers: “It’s not possible to be an attorney and a moral person.” In December, Adask, an articulate man who knows that many consider him a member of the lunatic fringe, began publishing a newspaper called The AntiShyster.

When Georgia Kubiak’s father died in 1981, leaving an inheritance in cash and land estimated at $700,000, the estate was handled by an attorney who was a longtime friend of the family. She and her brother each received about $60,000, but when nothing else was forthcoming, they asked the attorney for a complete accounting of the estate, including bank records. “He said, ’No, that’s my work product,1” Kubiak says. “Probably we would never have done anything if he had let me see them.”

Kubiak, living in Midland at the time, went to another attorney who told her she would have to come up with $20,000 to file suit against the other lawyer. Her money had gone to pay off loans, so she looked for another alternative. A second lawyer suggested she file a grievance with the State Bar of Texas.

She did. But to her astonishment, the very same Midland attorney who had said he would need $20,000 to take the case was appointed head of the grievance committee to investigate her claim. Worse, she says, the process shut her out.

“I was not able to hear what the lawyer said [about the dispute|,” Kubiak says. “I had no right of cross-examination. My witnesses were never called into the room.” The committee announced the verdict: Their fellow lawyer had done no wrong.

Kubiak started crying. “I couldn’t believe it,” she says. “He sounded like an advocate for that lawyer. I believed we had a system of justice in this country. And the system of justice simply does not work.”

Kubiak decided to do something besides cry. She joined HALT-Help Abolish Legal Tyranny. A nationwide organization started in 1978 by a Rhodes scholar named Paul Hasse, who grew up in Dallas, the group boasts 150,000 members, 10,000 in Texas. (Ironically, the HALT founder’s brother is attorney Mark Hasse.)

HALT’S aim is to make legal services simpler and more affordable. One goal is to lobby for provisions that allow simple transactions such as certain wills, divorces, and real estate documents to be handled by legal technicians or paralegals. HALT also publishes legal self-help manuals.

Surely no decent person could be against empowering citizens to solve their own minor legal problems. But the thought of mere civilians getting their hands on such provocative books as You and Probate apparently threatened some local legal beagles, In 1985, a Dallas subcommittee of the state bar initiated an investigation of HALT for “unlicensed practice of law” for selling these subversive volumes. The investigation fizzled.

“We wish they’d do it again,” says John Pomeranz, a HALT national legislative representative. “It was the best membership [building} device we ever had.” While the legal reform movement has outposts in every state, Texas is a major concern because of “the stridency of the bar and the aggressiveness with which they’ve tried to protect their little playground,” Pomeranz says. And because it has one of the largest, most active state organizations, Texas is naturally looked to by other bar associations for leadership-a frightening prospect.

“I get hundreds of calls,” Pomeranz says. “What people are angry about is that the system is unfair. There is no recourse for people.” And the impact of an unethical or incompetent lawyer on a client’s life can be devastating, especially to someone who is facing serious criminal charges or who is pressing a claim for negligence or medical malpractice.

HALT and several other consumer groups, such as Nader’s Public Citizen, have targeted the Texas bar. which comes up this session for Sunset review before the state Legislature. Under the Sunset process, each state agency must justify its existence every 12 years or be automatically abolished.

The bar’s unusual status as both trade association and state agency makes it a particularly inviting target. All attorneys in Texas must belong to the state bar to practice law. Cozily enough, discipline of attorneys is handled by 47 regional committees, made up primarily of other attorneys from their own districts. (In Texas, doctors are regulated by the State Board of Medical Examiners, and membership in the Texas Medical Association is voluntary.)

Texas traditionally spends less-by far- on attorney discipline than any other state. The State Bar of California in 1989 spent $274 per member on discipline. The Texas bar spent $63 per member.

Kubiak, who is now state director of HALT, is quick to point out that self-regulation is an inherent conflict of interest and can lead to cronyism, especially when discipline is meted out by lawyers who know each other. She quotes from a “secret manual” used by the bar for training members of disciplinary panels: “One of the many practical benefits to be derived from the present grievance committee setup is that many times the accused attorney is known by one or more members of the committee. These members may then be better equipped to evaluate the complaint.. .”

You can almost hear the conversation. “Oh yeah, that’s old Vince. Siphoned off a client’s trust fund? Vince would never do a thing like that. He ran last year’s toy drive. It s probably a big misunderstanding.” It’s not hard to see how members of a grievance panel could be influenced by friendship, expediency, politics.

Another guideline suggests that members take into account the reason behind the attorney’s misconduct. Did he or she steal the client’s money to pay big medical bills, or to put a kid through college? Well, then of course we sympathize. “If any underlying financial problems were unavoidable and innocent.. .as opposed to the self-indulged extravagances, a slighter discipline could be justified.” Gee, that’s not what judges ask most thieves before they put them on the van to Huntsville.

Another HALT criticism is that the grievance procedures are cloaked in secrecy; investigations are conducted, complaints dismissed, and private reprimands-the most common form of discipline-issued behind closed doors. While the system is designed to prevent frivolous charges from hurting an honest attorney’s practice, is it in the best interest of the public? Or is it an embarrassing and elitist anachronism?

Well, exhibit I-from the Texas Bar Journal, April 1989: A grievance committee found that a Dallas attorney “filed suit in the wrong county and failed to appear for the resulting transfer of venue hearing.” He also violated the rules of conduct in three other lawsuits, resulting in sanctions against his clients. In addition, the lawyer gave a client legal advice about the release of confidential information on former employees. The client followed his advice and, as a result, was tried and convicted on criminal charges.

The result? The attorney “accepted” a private reprimand. Emphasis on “private.” This means that if potential clients call the bar association and ask if any disciplinary action has been taken against this incompelent schlemiel, they will be told “No.” A world in which such creatures make $200 an hour is a strange world indeed.

For years, the Texas bar has vigorously fought all efforts at reform-even from within its own ranks. In 1973, the bar’s Schlinger Committee recommended that the organization adopt a centralized structure under a state Supreme Court disciplinary board, which would reduce the widespread inefficiencies and inequities in the system. For example, an attorney in Dallas might get off with a private reprimand for some action that would garner a license suspension in Ama-rillo. Some committees followed the rules; some didn’t. And some grievance panels were backlogged for years.

After the Schlinger Committee there was the Fisher Committee (1974), the Porter Committee (1974), the Hogan Committee (1975), and the Special Disciplinary Implementation Committee (1976). Despite the efforts of committees ad nauseum, ad in-finitum. the Texas bar has remained resistant to the one major change recommended by every group that studied it: a centralized system of discipline.

In fact, in 1981, apparently proud of its archaic disciplinary procedures, the stubborn bar invited the American Bar Association to Texas to examine its approach. The resulting report by ABA examiners was so scathing that the Texas bar buried it until 1983, when it was unearthed by a reporter.

Commenting on the bar’s failure to listen to its own committees, the ABA report said: “.. .It is clear that the self-interest of the bar to preserve the status quo prevailed in the retention of an unworkable decentralized structure, despite its effect on the public interest.. ,We believe meaningful changes have been delayed too long and that the public interest demands implementation of immediate reforms.” It quoted one member of the bar as saying that chief among the problems with the grievance system were “dependence upon volunteer staffing, inadequate funding, and what 1 call the ’good buddy’ system.”

A great example: In 1987, a grievance filed against a Palestine attorney for punching a Dallas attorney during a jury trial recess was handled with utmost secrecy. Though the attorney was found guilty of professional misconduct, his case didn’t follow state bar rules. Instead of being given one of four mandated penalties-public or private reprimand, suspension, or disbarment-he was handed a 90-day probation. The lawyer? James Parsons, now president of the State Bar of Texas.

Throughout, the ABA report demanded “immediate action” addressing the serious deficiencies in the Texas system. That was 10 years ago. Today, almost none of the recommendations have been put into place.

Last fall. HALT and other legal reformers were dealt a serious setback when the Sunset Advisory Commission refused to go along with its own staffs recommendation that attorney discipline be handled by either the Texas Supreme Court or a separate agency. Even before the meeting started, Kubiak got an inkling of how things were going to go. She says Dallas attorney Darrell Jordan, past president of the state bar, shook her hand and said with a smile: “’We’re glad to see you today.. .because we’re going to squash you.”

Kubiak says Jordan’s remark was in jest. In fact, the lawyer had supported some reforms, But she believes the message was clear. “They’d already made a backroom deal with their lobbyists,” she says.

So Kubiak wasn’t surprised when the commission also rejected a proposal made by HALT and Public Citizen that a separate consumer protection agency be established to handle the gripes about attorneys that don’t necessarily involve disciplinary rules. These less serious complaints-that an attorney doesn’t return phone calls, doesn’t submit detailed bills, doesn’t keep a client informed-make up the bulk of grievances filed against attorneys.

Other proposals-that private reprimands be abolished, that all hearings be open to the public after an initial investigation ascertains that a genuine complaint exists, and that records of attorney discipline be accessible to the public in the county in which the attorney practices-also were rejected last year by the Sunset Advisory Commission. So much for reform.

A frustrated Kubiak says that for the last two years, the state bar has put no money into the client security fund, which reimburses customers ripped off by their lawyers. But last year, in response to escalating consumer criticism, the bar spent $200,000 to lobby for its own reforms, which are likely to be accepted during this session of the legislature. Attorneys statewide voted to approve those reforms, which included doubling their dues, in November.

Kubiak says the bar’s reform measures don’t go far enough; some, in fact, may leave consumers worse off than before in terms of what they are allowed to know about the character and competency of the legal elite. For instance, the bar wants to eliminate client immunity. “Under the new rules,” Kubiak says, “you’re not protected from a libel or slander suit if you file a grievance.”

Kubiak is especially galled by a proposed “reform” that would keep confidential the records of attorneys on probation for substance abuse. “You have no right to know if you are dealing with a drug addict or a mentally impaired attorney,” says Kubiak.

Reformers have little hope that the Texas Legislature will show backbone and reject the bar’s proposals. Remember, lawyers make up the dominant occupational group in the Legislature.

Still, Kubiak is not discouraged. She thinks that major legal reforms are inevitable, that the Nineties will be the decade when consumers finally demand-and get-accountability from lawyers. The revolution she foresees may take time, picket signs, and lots of lobbying in Austin, but she believes the Texas bar ultimately will be forced to make significant changes or be faced with widespread consumer revolt.

Until that day. Kubiak isn’t sitting back waiting. She has also filed a lawsuit against the attorney who handled her father’s will. And she’s far from alone. Call it courthouse karma. In escalating numbers, clients are turning the tables, charging their attorneys with legal malpractice.

IN THE EARLY EIGHTIES, GEORGE WATSON and A. Starke “Tracy” Taylor (son of former mayor Starke) were hot. Everything the young Dallas real estate developers touched seemed to turn to money. Regional banks, especially FirstSouth in Little Rock, Arkansas, were literally throwing cash at them. Watson and Taylor would acquire and develop projects, then split the profits with the bank. It was a fairly typical relationship for those go-go times.

Now they’re broke. They’ve spent almost five years battling with the government to stay out of jail. And some people claim there’s a lawyer to blame.

The troubles began in 1985, when First-South came under scrutiny by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, which learned that Watson and Taylor controlled about 26 percent of the FirstSouth stock and concluded that they had conspired to obtain a controlling interest in the bank.

After FirstSouth foiled, Watson and Taylor were sued for $300 million in damages by the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation, and the government began a criminal investigation of the developers. They lost their $15 million investment in the bank and spent millions of dollars defending themselves. Watson and Taylor finally made a deal with the U.S. Attorney’s office: their cooperation for immunity.

In their eyes, Watson and Taylor had done nothing wrong. Remember, however, our lawyer-driven credo: In America, someone is to blame for everything. So last fall, they filed a $102 million suit against their attorney, John J. Kendrick Jr., for legal malpractice, breach of fiduciary duty, and deceptive trade practices. They claim that Kendrick, beginning in 1983, repeatedly assured them there was no problem in buying FirstSouth stock and, in fact, encouraged them to do so. The two began purchasing the stock and when Taylor got to 9.9 percent (the legal limit is 10 percent). Kendrick began purchasing shares as trustee for a trust set up for one of Taylor’s children.

Watson and Taylor charge that Kendrick never told them that, combined, they were limited to ownership of less than 10 percent of FirstSouth’s stock-and further, that the lawyer charged substantial fees for advice that later cost them a fortune and their reputations. In addition, they say that Kendrick never advised them that he and other lawyers at his law firm of Akin. Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld were also representing First-South in its stock offering-a possible conflict of interest-and that Kendrick and a family member also bought stock in the bank.

The suit named not only Kendrick, but more than 200 other attorneys at Johnson & Gibbs, where Kendrick worked when his relationship with the developers began, as well as those at Akin, Gump. The theory in bringing all these lawyers into the suit even though they did not personally advise the developers is simple. They were partners, and they all have malpractice insurance policies. (Again, the Deep Racket Theory of Litigation: Don’t find who’s responsible, find the one with the money.) All defendants have filed general denials of all Watson and Taylor’s claims, and Kendrick declined comment on the charges.

The case illustrates one reason that more suits are filed in Texas for legal malpractice today than ever before, even though 10 years ago it was almost impossible to find an attorney to sue another lawyer: the savings and loan debacle.

The FSLIC (now Resolution Trust Corporation) and the FDIC have vigorously pursued lawyers who have had a part in the destruction of the nation’s S&Ls. The Larry Vineyard case is a prime example. A Dallas attorney who left Jenkins & Gilcrest to head a savings and loan. Vineyard is now in jail for fraud. His former partners at Jenkins & Gil-crest, even if they had no role in the bank’s downfall, were also sued by the FSLIC. The case was settled out of court last year, as are 90 percent of legal malpractice suits.

But the fallout for the legal profession has been that more and more clients are now willing to file suit against attorneys, and lawyers are willing to take the cases. “It brings up real problems for law firms,” says Arne Sorenson, a Washington, DC, attorney who handles legal malpractice cases. “There are questions about the liabilities lawyers bring with them when they are hired.”

Lawyers bemoan the rise in legal malpractice suits. They say that the bar has become far less collegia!, less personal. But James Parsons, president of the state bar. says that if a case is valid, it should be tried. “It helps clean up the system.”

Al Ellis, former president of the Dallas Bar Association, has sued lawyers for legal malpractice. “1 believe in the system,” Ellis says. “Why should he [a lawyer] be any different? You live by the system and die by the system.”

There’s even a book for consumers out now called How to Sue Your Lawyer by New Jersey attorney Hilton Stein, who specializes in legal malpractice. (It has an endorsement by Morton Downey Jr.: “Sue all the lawyers!”)

And there are some other encouraging lights on the horizon. The law profession has seen a reduction in so-called “Rambo tactics” (e.g.. badgering a witness) since a 1987 Dallas bar task force produced “Rules of Professional Conduct.” which were adopted by the courts about the same time federal judges handed down the Dondi ruling, an opinion that addressed the same issues. Even Bickel & Brewer, a Dallas law firm well known for its obnoxious tactics, has softened its approach somewhat. Indeed, the firm proved downright endearing last year when it “adopted” a snake at the Dallas Zoo.

One alternative available to clients who feel they have been ripped off by their attorneys is the state bar’s client security fund, which in January began to pay as much as $30,000 per client (up from $20,000) to those who have sustained a loss through “fraud, theft, and misappropriation of funds.” For clients who have lost more than the limit, however, a lawsuit is the only recourse. And don’t forget the contingency fee; yet another lawyer will get 30 percent.

One healthy side effect of lawyers’ willingness to go after each other may be that attorneys become more careful about how they handle clients, provide more accurate bills, and perform the work they are paid for. “This is a service industry.” says an attorney at Fulbright & Jaworski. “Ultimately, you are at the beck and call of your client.”

IT WAS CLEAR LONG BEFORE HIS ARREST that Waxahachie resident James Kozacki was becoming obsessed with getting back at attorney James Planners. His phone was disconnected after he ran up huge bills talking to people all over the country to find out more about Hanners.

His efforts at playing the private eye paid off. Kozacki discovered that Hanners was under investigation by the U.S. Postal Service for insurance fraud. Hanners had received monthly disability checks after a psychiatrist diagnosed him as unable to practice law due to depression. Apparently he wasn’t that depressed-or at least not blue enough to forsake his law practice. Kozacki invited a postal inspector, Adam Thomas, to attend his town meeting. Thomas, citing postal department policy, would neither confirm nor deny that Hanners is under investigation. Hanners did not return D’s phone calls.

Over the years, the accused attorney has left a trail of furious clients and investors, garnering the reputation of a ruthless legal bully who uses his position as an attorney to take people’s money, and who threatens lawsuits to silence criticism. Hanners has filed a federal suit against Kozacki and another couple who filed grievances against him.

But Kozacki’s persistence may have paid off. At press time, Steve Young, regional general counsel for the state bar, said that a disciplinary lawsuit against Hanners will be filed in state district court. “We will be pleading for a disbarment,” Young says.

In addition. Ted Steinke of the specialized crime division of the Dallas DA’s office confirmed that some of Hanners’s activities are under investigation.

The Waxahachie feud actually points to abigger issue, says a prominent Ellis Countyattorney. “The question is: Why has oneman with a cardboard sign been able to dosomething the state bar hasn’t been able to dofor years?”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

Mayor Eric Johnson’s Revisionist History

In February, several of the mayor's colleagues cited the fractured relationship between City Manager T.C. Broadnax and Johnson as a reason for the city's chief executive to resign. The mayor is now peddling a different narrative.

Media

Will Evans Is Now Legit

The founder of Deep Vellum gets his flowers in the New York Times. But can I quibble?

By Tim Rogers

Restaurant Reviews

You Need to Try the Sunday Brunch at Petra and the Beast

Expect savory buns, super-tender fried chicken, slabs of smoked pork, and light cocktails at the acclaimed restaurant’s new Sunday brunch service.