THE GIRLS HAD PLANNED METICULOUSLY. PAMELA’S MOTHER WAS going out of town. After notifying the police that her home would be empty, she had arranged for her 14-year-old daughter to spend the weekend with Sarah, also a freshman at Highland Park High School. That Friday night, Sarah’s parents dressed for the Junior League Ball, one of the social season’s premiere events, and at about 6 p.m. dropped the teenagers off at nearby Highland Park Village, where the smell of Mexican food and popcorn mingled in the January night air. The understanding was that the girls would eat dinner and see a movie. But the teenagers had organized a premiere social event of their own. The invitations had gone out-not to their own classmates, but to 100 kids from the higher grades. (After all, who needed to impress fellow freshmen’!) They sneaked back to Pamela’s house on Amherst and, being thoughtful, put much of her mother’s furniture and knickknacks in the garage.

Later, photographs of the inside of the house were blown up to poster size and displayed inside the courtroom at the University Park City Hall. While many of their parents were dancing in elegant ball gowns and tuxedos, the teenagers had destroyed their neighbor’s home. It looked like the aftermath of the movie Animal House, with beer cans and bottles strewn everywhere, the carpet ruined by cigarette burns, dirt from potted plants, and spilled drinks. A wall had several holes where it had been punched or kicked in, and a chandelier was broken.

The police officers, called by irate neighbors complaining about the noise around 10 p.m., had peered in the windows of the house. It was stuffed with teenagers, far more than the 100 invited. Apparently crashers had heard the news of the soiree. Booze was everywhere; it seemed as if all the kids, many not old enough to get a driver’s license, had drinks in their hands. Deciding that this was more than they could handle alone, the officers called for another squad car and waited.

But they’d been spotted. From a second-story window, teenagers threw eggs and a few cans and bottles at the police car, then began climbing onto the roof and jumping through windows to get away. In a search, officers found not only beer and wine, but bottles of hard liquor. Out of an estimated 130 partiers, police managed to detain 100 teens, all students at Highland Park High School. Twenty-seven of them, age 17 or older, were slapped with minor in possession citations.

Bob Dixon, chief of the University Park police and fire departments, decided a little shock therapy was in order: For the first time, he notified the Park Cities parents of those students under 17, who could not be charged, in writing and asked them to come to a meeting. He was worried. This wasn’t the first party where things had gotten out of hand. The school year had started off that way when Highland Park police were called to two alcohol-soaked events on the same night in August. At one, they confiscated a .30-caliber Winchester from an 18-year-old boy who told police he was shooting in the air in an attempt to calm things down after a party attended by 200 kids at his home careened out of control. At the other, cops confronted 50 teenagers armed with clubs and baseball bats on Fairfax Street. The young girl who had thrown the party while her parents were out of town said that uninvited kids from another school had crashed the party to start a fight.

These were not isolated events, rarities at which “bad” kids acted out their aggressions. Police officers say that on any given night in the Park Cities there’s at least one party involving kids and booze, all with the potential to end in disaster. At times, parents are those responsible, providing the alcohol themselves or at least acquiescing, rationalizing that “it’s only booze,” not drugs, and that the teenagers won’t be out driving.

The idea of teenagers throwing wild parties while their parents are away may not be new or shocking. But the increased frequency of such affairs-and a new edge of violence-has alarmed police, educators, counselors, and parents in Dallas’s more affluent neighborhoods, especially the Park Cities.

Those who work with young people say that in many ways, wealth and privilege bring their own problems-and in fact may mirror the difficulties faced by minority children in ghetto areas, where neglect as well as emotional and physical deprivation are common. And as the children reach adolescence and issues of identity, career goals, materialism, and sexuality come up, the teenagers feel a new pressure: pressure to succeed, to achieve the same level of affluence and prestige as have their parents.

More and more families are facing these issues, from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, to River Oaks in Houston. While the 1980s are often called the Decade of Greed, they also saw an unprecedented growth in prosperity, minting more millionaires than any American decade since the 1880s. A recent book called Children of Paradise, by the senior psychologist for the Beverly Hills Unified School District, outlines many of the challenges facing prosperous, achievement-oriented parents in the 1990s.

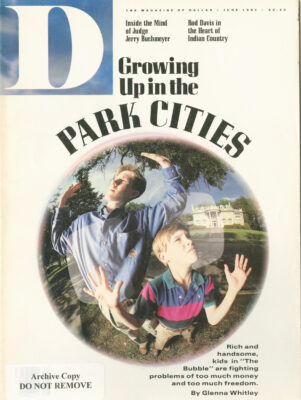

In Dallas, the same issues come up in wealthy neighborhoods from Duncanville to Piano. But the enclave with the highest concentration of well-to-do parents is the Park Cities. Far more than any other area of Dallas, Highland Park and University Park exert a strong, almost magnetic pull on those who have “made it,” especially those interested in raising a family. This place has the image of a safe haven, a protected environment where education is worshipped, where unsavory facts of life are kept at bay.

That’s why they call it The Bubble.

STROLLING THROUGH THE halls of Highland Park High School is like walking into the pages of Seventeen magazine. The girls are fresh-faced and polished, their haircuts and makeup sophisticated and sleek. The boys are clean-cut, robust. all-American. Their clothes look straight off the rack at The Gap or Harold’s, with a touch of Ralph Lauren and Neiman Marcus here and there. In the students’ parking lot, the new Jeeps and Explorers and Miatas and racy Toyotas far outnumber mom’s automotive hand-me-downs.

Students with backpacks stream through the halls of the sprawling red brick building (oddly resonant of nearby Southern Methodist University), past yellow lockers, past the school planetarium, through the $2.8 million science wing, around the art studios filled with natural light, past the closed-circuit television studio. The football team’s motto: Nothing But the Best. There’s a definite attitude that nothing is too good for these students, that this is the cream of the academic crop.

And that’s certainly true. At HPHS, the average IQ is 115. More than 95 percent of its graduates go to college, with as many as 50 percent of those choosing schools out of state. Ninety percent of HPHS seniors take college Advanced Placement exams, compared to the national high-school average of 15 percent. And in 1990, the district reported that the school’s average SAT score rose 24 points; nationwide, it dropped.

They’re not only brainy, they’re brawny; the Highland Park High School athletic program has been named The Dallas Morning News’s All Sports Champion five times in the last six years. Football is played in a stadium lined with $900,000 worth of artificial turf; a $100,000 electronic Scoreboard keeps the touchdown tally. Tennis players volley in the air-conditioned Seay Tennis Center, and the swimming team bobs in the indoor pool while listening to their coach.

Moms and dads crowd the stands at the games and activities. During the week, they run the cafeterias. “Our parents are into everything we do,” sighs Jonathan* an earnest, wiry senior at HPHS. “Sometimes it’s too much. It can make you crazy, but you’re glad they’re there.”

Jonathan and five of his friends are sitting on sofas and overstuffed chairs around the perfectly decorated living room-not too trendy, not too traditional-of one of those quintessential Park Cities homes, a two-story brick edifice that almost fills its lot.

The three girls and three boys are talking about what they’re going to do when they graduate this summer. “In Highland Park, it’s not a question of if you’re going to college,” says Jonathan, “it’s where.” In their senior class of 294, they know of only two students who do not plan to enter college this fall. These two girls are definitely strange, they say. They got in with the wrong crowd, the freaks, the kids who wear all black, with headbands and purple suede boots, and stand on the corner of “Freak Street” near the high school and smoke cigarettes before class.

Though that seems to be the extent of their rebellion, the freaks evoke scorn from this group, and from many of the other students. They can’t understand why the outsiders don’t dress “normal, preppy, like us.”

Being conspicuously unconventional is not an attribute highly prized in the Park Cities. “It’s hard here to be different,” says Natalie*, an athletic, healthy blond with a ponytail, wearing shorts and a sweat shirt. “Parents don’t want you to hang out with so-and-so, he wears an earring.” But the kids know a secret: Sometimes the ones who look the part, the preppier-than-thous, are the real hell-raisers.

Slight, perfectly groomed Andrew* moved here in the fifth grade, making him late to join the group, which started kindergarten together. Now they go on group dates together-the Park Cities version of teen romance. He loves the idea that everywhere he travels, when he says he’s from Highland Park, people automatically say, “Oh, that’s where the rich folks live.”

But the teens know The Bubble is not representative of the real world-for one thing, the Park Cities are overwhelmingly white. What’s it like growing up where the only black or brown races they see belong to maids or housekeepers? “I think there’s a lot of racism,” says Natalie. “There are no black students at Highland Park, not one. Around here, the image of the Mexican is the truckload of guys who do the yard.”

These kids say their own parents aren’t prejudiced, other parents are. Natalie was shocked and outraged when a friend’s mother told her she “must smell like a nigger,” because she was dressed in sloppy clothes. And it bothers her that people with the wrong skin color can get stopped by the police in the Park Cities simply for walking down the street.

While many kids like Natalie feel the injustice, others obviously learn those lessons well. During one high-school basketball game last year against McKinney, some of the HPHS students and supporters started chanting “white trash, white trash.”

Which brings us to the party on Amherst and drinking. All six of these students say they drink, but none will admit to smoking pot or using cocaine. Natalie was too intimidated to drink as a freshman, but like many of her friends, she overcame that fear as a sophomore. None of them think they have a problem with alcohol. But in their sophomore year, they say, it got positively trendy to go to rehab. “I swear, it was the thing to do,” says Dana*. Now, she thinks that only those with real problems go.

They agree that the parties have gotten worse during their four years in high school. They all know kids who have been injured in fights. Out of about 300 seniors, an estimated 200 will throw parties their last year in school. At almost every one of them, kids will be drinking. And some will get out of hand.

But the major thing that bothers these teens is not booze or racism or conformity. It’s competition for grades, and it starts in freshman year, as they begin to build The Transcript-their ticket to a good college, Parents have high expectations. “My parents think of it like, ’We’re giving you so much, we expect you to respond,’” Natalie says.

“Class rank is a big concern,” says Jonathan. “You’re in competition with the guy in front of you.” It makes them angry that some of their peers take easy courses, or worse, get their parents to do their projects. They talk about two girls (“Queens of the Social Scene”) whose mothers are notorious for being deeply involved in every facet of their daughters’ lives, down to composing their poems and doing their homework, or suggesting that the family go out of town to avoid embarrassment if the girls don’t have a date for the dance. Natalie remembers discovering one mom writing the outline for the daughter’s major term paper. “I’ve been really busy,” was the girl’s embarrassed explanation.

“It makes me so mad,” says Jonathan, “because they are so far ahead of me in rank.” Attending HPHS is particularly hard for Dana, who’s dyslexic and has to take modified classes. At a school where it’s as cool to be a brain as it is to be a quarterback (well, almost), it’s not easy to be labeled “learning disabled.”

All six of these students know that they are in the third quarter of their class, and which students rank above and below them. At other schools, they might be in the top 10 percent. But it’s hard competing with a kid who has a summer job at the Super Collider. While others have set their sights on Princeton, Yale, Stanford, these kids are looking at colleges like Vanderbilt or the University of Texas-fine schools, but not the top of the top. Natalie is thinking about law school, unless she decides to have a family. Then maybe she’ll teach. Jonathan wants to be in real estate and finance. Ed simply wants to get into business, to succeed financially as his stepfather has done.

“I may go to SMU,” says Kate, who is considering advertising. “My dad loves SMU.” Her father has never pressured her, or even mentioned that she should consider his alma mater. He doesn’t have to, she says. It’s clear where his enthusiasm lies. Going to college in the same town where she attended high school is not much of an adventure to Kate. Still, it’s a comfortable alternative.

An HPHS teacher says her students call it “bubble-hopping.” They go from HPHS to another enclave, a private school where most of the students come from homes similar to theirs. Then, they marry and return to the same environment, either here or in another city’s upper-income bubble. Jonathan and Natalie and their friends all want to return to the Park Cities after graduation.

“It is isolated and protected,” says Jonathan, who seems to have the most awareness that the Park Cities is not like other places. “Leaving this little Mr. Rogers’s neighborhood is kind of scary. But I have to do it. I have to see what the real world is like.”

BOTH DRESSED IN BLUE JEANS.

Susan and Marc Hall scrunched into school desks alongside women in designer leather and men in pin-stripe suits, listening as four elementary school counselors began their presentation. The forty something couple had picked up their confetti-sprinkled name tags at the school cafeteria for the Positive Parenting Gala in February, a one-night seminar chock-full of lectures on kids and education. As the Halls made their way to the classrooms, they greeted friends and neighbors.

When the Halls lived in far North Garland, they realized something was missing. “It was a big suburbia,” says Susan. The residents came and went; little seemed permanent, rooted. She’d grown up in a tiny East Texas hamlet; he’d been raised in neighborly Oak Cliff. So, when the former Steak and Ale supervisor decided to open his own restaurant, they began looking for a small town to start a business and raise their children. Six years ago, they found it in the Park Cities. The Halls now own three restaurants within two blocks of each other, and their house is only a few streets over.

“I like the fect that my children can walk down the sidewalk and say hello to the mayor,” says Susan. “And it’s a pretty place to live.”

It really is just a small town. Though they live five minutes from downtown Dallas, devoted Park Cities residents repeat this like a mantra. This is a place where a neighbor two streets away called up Laurie Harper, a mother of four, to ask if she knew her 4-year-old son, supposedly napping, had escaped and was sauntering across busy McFarlin Boulevard. Where teenagers graduate from high school with the same friends they made in kindergarten. Where mothers work in the school cafeteria, swapping gossip heard at the Junior League meeting the day before, and dads coach T-ball teams at the YMCA.

Making the decision to move to the Park Cities wasn’t easy for the Halls. Marc and Susan had attended SMU in the late Sixties, though neither was from a well-to-do background. When the Halls finally sold their house in Garland and put down roots in the Park Cities, the boom hadn’t busted; everyone seemed to be making a million dollars, or at least talking as if they did. “You hear so many horror stories about living in The Bubble, how insulated it is from the real world,” says Susan. Discovering there were children at the elementary school who wore Rolex watches did nothing to erase that “spoiled rotten” reputation.

They had looked for homes in other parts of Dallas County. But for the Halls and many others, the Park Cities, far more than any other area of Dallas, proved irresistible. Writer Prudence Mackintosh calls the place “pretty seductive.” Since 1972, she’s lived in the Park Cities, chronicling life as a mother of three sons in The Bubble.

“We moved here rather innocently,” she says. “We found a house we could afford that came with free neighborhood tennis courts and a neighborhood swimming pool.” She can walk to La Madeleine bakery or to dance performances at Southern Methodist University. It’s six minutes from her husband’s downtown office. Her three sons could play at the creek or ride their bikes to school and the small public library. Add to that “a police force that will figure out how to turn off your water when you’ve forgotten how and responds to calls such as ’birds in the chimney,’ ” Mackintosh says.

And there’s the deep obsession with children and education-and the top-rated public schools that preoccupation has produced. It all combines to lure even those who can’t really afford it to the protective dome of The Bubble.

But a better description might be The Golden Doughnut Hole. Surrounded by the city of Dallas, this enclave of 6 square miles-bounded by Turtle Creek on the south. Northwest Highway on the north, Central Expressway on the east and the Dallas North Tollway on the west-is a mentality as much as a geographic location or a school district.

Take the newspapers, for example. The Park Cities People has run a long, loving feature on maids and housekeepers, and is among the few weeklies in the country to have special sections on furs, polo, and the annual best-dressed list. A regular feature called Family Portraits last year spotlighted an attorney and his wife, a former Miss Oklahoma, who, along with their two kids, celebrated their parents’ anniversary on a Mediterranean cruise with 30 family members.

And the shopping: The Park Cities’ groceries had valet parking long before that convenience made it to North Dallas. Indeed, the first Simon David gourmet grocery was located on the fringe of the Park Cities, counting on cooks with connoisseur tastes to keep it in business.

And nestled in the center of the Doughnut Hole is the Highland Park Shopping Village, which boasts chic boutiques for Calvin Klein, Hermes, Ralph Lauren, Chanel, and Guy Laroche-as well as a Godiva Choco-latier. In Snider Plaza, near SMU, residents can pick up the latest Caldecott winner for junior at Rootabaga Bookery, or buy a $300 party dress for an 8-year-old girl at the Childe shop.

Certainly, rubbing elbows with the eminent is another appeal. Some Park Cities residents are known all over the country: Former Governor Bill Clements lives here, as do renowned businessman Ed Cox and most of the members of the Hunt family. Kern Wildenthal, president of Southwestern Medical School, moved here when he took the job. Though H. Ross Perot lives in North Dallas, Ross Jr. resides here.

In ZIP code analysis terms, 75205 is an amalgam of Highland Park’s “Blue Blood Estates” and University Park’s “Money and Brains” categories, which take in only 2 percent of American households, that percentage with the highest median annual income. Mercedes, Suburbans, and Jeeps with car phones fill the driveways of mansions along Beverly Drive. Lakeside Drive, Armstrong Parkway, and Versailles Avenue.

Though the Park Cities are also home to the single mother and the two-income family scraping to afford $1,500 rent on a cottage with two bedrooms-so that their kids can attend Highland Park schools-most of the residents are professionals, with an overwhelming number of doctors, lawyers, and chief executive officers. A decade ago, people crowding into the Park Cities started the phenomenon of tear-downs, bulldozing bungalows to erect new houses that mimic the stately older homes while pushing the envelope of square footage possible on a 50-foot lot.

The push to live here has propelled home prices ever upward. The average house in the Highland Park Independent School District is worth a whopping $373,156, a price tag that in some suburbs buys a mansion. “The house we live in now is half the size of the house we lived in up in Garland,” Susan Hall says. One estate was recently listed for $7.9 million; four others were on the market for $3.9 million and more. The tear-down craze cooled in the late Eighties, but has begun to creep back.

After making their decision, the Halls say they have not regretted it. They first opened Amoré, an Italian restaurant in Snider Plaza. With that success, Cisco Grill followed, joined by Peggy Sue BBQ in 1990. They’ve made genuine friends, as have their two daughters, who attend University Park Elementary School. “We’re here to stay,” says Marc.

But at the Positive Parenting Gala, they listen attentively while the counselors for the grade schools talk about “Raising Responsible Children in an Affluent Community.” Though the Rolexes on the wrists of grade schoolers have largely vanished with the Eighties economic boom, this is not merely a theoretical concern for the Halls.

Susan tells this story: In her car pool before spring break, one of her second-grade charges mentioned that she’d be visiting “the ranch” for the holiday, a popular weekend destination for many of the Halls’ friends. After Susan asked how long it took to get there, the girl said, “Oh, about an hour.”

That didn’t seem like a bad drive, Susan offered.

“Oh no-we go in the jet,” the girl said matter-of-factly.

“My daughters have friends that are going skiing for 10 days, or to the Bahamas for a week,” says Susan. “They want to know why we can’t do that. You just have to teach them how to handle it. We have to sit down and explain why one month we can get some extras, and not the next.”

The Halls and their parenting comrades say they hear stories about youngsters and their silver-plated possessions all the time: the second-grader with a TV, a VCR. and telephone in his own room: the family whose Suburban has a TV, complete with a Nintendo in the back; the $75 outfit on the fifth-grader on the playground; teenagers with $250 Louis Vuitton purses; the boy who gets a Porsche, direct from Stuttgart, simply for turning 17. And it’s not just the kids; Park Cities parents also hear about the mom who spends $10,000 a month on clothes-just for herself.

Last year, a “black-and-white” deb party featured huge rounds of caviar and pate. Dick Chaplin’s Cotillion, a dance-and-manners class popular with Park Cities parents, begins in third grade. The invitation-only Junior Assembly puts on mini-deb parties in fancy spots with costumes, favors, and photographers.

“What do they have to look forward to?” says Sherry Latson, a family counselor and play therapist. “There are kids who have their birthday party at the Mansion, and go to Europe regularly, They go skiing two or three times a year. They have credit cards with no limits. A lot of kids tell you they’re spoiled. They almost flaunt it, like, ’See, I have a lot of things. I count for something.’”

The Halls are not the only ones feeling the pressure. Of all the stories the weekly Park Cities People ran last year, the one that drew the most overwhelming response was a simple proposition: Should students at Highland Park’s public schools wear uniforms? The answer from parents: a resounding “Yes!” The pressure to dress in the latest fashions, many parents wrote, was becoming overpowering, leaving parents confused about how to respond.

“I don’t want to raise materialistic kids,” says clinical psychologist Ben Albritton, who has two children in HP schools. “But when everyone else is wearing $60 sneakers, you hate to go to K Mart and buy Keds.”

The pressure can be very real. Psychotherapist Lois Jordan, who grew up in the Park Cities and stayed there to raise her own children, remembers an example from six years ago, when her daughter was in the fifth grade. “The principal and counselor had to meet with all the girls and talk to them about putting pressure on kids who weren’t getting their clothes” at a certain boutique. “They were ostracizing them.”

Some of the pressure among teenagers to drive fancy cars and wear designer clothes is a result of competition among parents, says Marilyn Wright, supervisor of the Highland Park Student Assistance Network Service.

Still, setting limits isn’t easy when money is no object. “It’s hard to say no,” says Wright. “If I have the resources and my child wants it, is it wrong to give it to him? That’s what parents are asking.”

In fact, it can be wrong, says psychologist Albritton-unless values are dispensed with the material possessions. “Gratification interferes with the growth process,” he says, and produces what he calls materialistic psychosis. “They don’t learn to wait, to plan. Money is not seen as a limiting factor. And among the really wealthy, that essential separation of kids and parents never occurs. It interferes with young adults seeing themselves as independent, productive citizens.”

Affluence doesn’t have to be a curse, Albritton says; in fact, it can buy invaluable family time and experiences. But parents have to be aware of its hidden dangers. He tells Park Cities parents to help their children focus on what they have to give to the family, through chores. “Expect them to contribute to savings for college, a car,” Atbritton says. “Let them pay for the difference in the cost of a regular shirt and a Polo, if that’s important to have. And make a conscious effort to praise character, rather than superficial things.”

So far, that kind of parental peer pressure has been easy to resist, says Susan Hall. Most of the Park Cities friends they’ve made since moving are much like them-casual, laid-back, determined not to raise overindulged children who don’t associate work with its rewards. But she knows it will get more difficult as her girls grow older.

“I want to get them out there in the real world, not thinking mom and dad are standing behind them with a blank check,” Susan says, “I want to break The Bubble.”

DOUG THEODORE LOOKS AT THE WELL-dressed, sophisticated teenagers in the Park Cities and sees a generation at risk. “These are overindulged, spoiled rich kids with all the money they need, which is too much,” says Theodore bluntly. “I’m laughed at by the folks from classically minority areas when I talk about the similarities in these kids and their kids.” But many of the problems he hears from Park Cities teenagers are the same as those in the ghetto: parents who are alcoholics or drug users themselves, broken homes, blended families.

Theodore, who took an 82 percent reduction in his income as a general contractor to head the Chemical Awareness Council (CAC) of the Park Cities, is a product of the world he describes. An “indulged” only child, he attended private school in Arkansas, and moved to Dallas to attend Southern Methodist University in 1965. Except for one year, he’s lived in the Park Cities ever since. The first of his three sons entered Highland Park public schools in 1972; the last will leave in the year 2002.

Barrel-chested, gruff, Theodore is exasperated by what he sees of his neighbors’ methods of parenting. He includes himself in this indictment, saying it took him and his wife much effort to unlearn parenting skills ingrained in growing up.

“I was parented on a gold platter, even though we weren’t wealthy,” says Theodore. “We come from parent swho grew up in the depression, in World War II. Those dads said, ’You’ll get the best of everything.’ But we didn’t get that valuable experience of going without, working hard.”

Oddly, one of the most common problems he sees for kids in affluent, fast-track environments is old-fashioned neglect. Not neglect of their physical requirements, but their emotional needs.

Psychotherapist Jordan, who has worked with kids from both poor and wealthy areas, agrees: “A kid in West Dallas may grow up without a sense of bondedness with his mother because she’s out doing drugs. In Highland Park, the mother’s not there because she’s involved in PTA, Crystal Charity Ball, on a trip to Paris. It doesn’t matter to the kid; he just knows she’s not there.”

Sometimes, says one teacher at Hockaday, an exclusive private school for girls in North Dallas, parent surrogates such as nannies and housekeepers perform so well that “it’s hard to tell if they [the kids| are talking about their mothers or their maids.”

But those arrangements don’t always work. Child therapist Sherry Latson tells about a family she knows: The father is a doctor, the wife works part time and is an active volunteer. Every six months brings a new nanny and a whole new set of rules and expectations.

The result can be serious emotional problems. Sam Brito, director of the substance abuse program at Southern Methodist University, sees students who grew up in the Park Cities and enclaves like it. He says it is often easier to work with street people. “With the rich kids I see a sense of detachment, a result of poor bonding between parent and child. They (parents] will essentially say, ’I’ll pay for you to go to college, but I don’t want to be bothered.” You’ll ask kids what they’re doing for the holidays. ’Going to Colorado skiing.” Not going home? ’Naw, my parents are in Europe.’”

Albritton has also seen the opposite problem: too much sympathy. He describes the Park Cities parent who did drugs with his daughter while she related her sexual exploits. After the daughter was hospitalized for drug treatment, the father tried to get the girl released to go on a two-week ski trip.

Most Park Cities parents make adjustments when the problem is pointed out to them, therapists say. They just need to be reminded that they are important to their kids, that their input counts. But some, obsessed with work or their own needs, are reluctant to spend time with their offspring.

And even in the Park Cities, which one pastor describes as the “last bastion of the stay-at-home mother,” teachers and therapists see latch-key kids and others with minimal supervision. One father says he let his young son spend the night with a friend only to discover that the parents had gone out for the evening, leaving the children with a caretaker who spoke no English.

“I have kids who come in and say their dad leaves at 7 a.m. and comes home at 1:30 or 2 a.m.,” says HPHS Principal Donald O’Quinn. “The only time they see their father is when they get in trouble.” O’Quinn says that it is not uncommon for parents of HPHS students to leave town for up to two weeks, letting their teenagers stay home alone.

“I had one father who phoned and asked me to call him if his daughter wasn’t in school,” O’Quinn says. Sure enough, the next week, the senior missed class. O’Quinn called the father’s office, only to discover he had gone to China for six weeks and left his daughter on her own.

“I think you’re very foolish to leave a teenager at home alone,” O’Quinn says. “You’re assuming she has enough strength to say no to all the friends she wants to be popular with.”

This year, the HPHS Student Assistance Network Service has helped dozens of students who are bulimic, alcoholic, or suicidal. “The fact that these kids, with all their advantages, would even think about suicide is amazing,” says Jerry Smith, HPHS teacher and a student advocate with SANS. The school’s five student support groups are an outgrowth of SANS.

Drug and alcohol use is higher at HPHS than the national average, according to a 1990 survey of HPHS teens that measured levels of use of 10 different controlled substances. The results: Only use of marijuana was lower. In two categories-heroin and steroids-Highland Park kids indulged at the national rate. But HPHS use was higher in alcohol (14 percent), tobacco (13 percent), cocaine (2 percent), LSD and PCP (2 percent), inhalants (4 percent).

Drinking is rampant; a staggering 96 percent reported using alcohol at some point, and three-fourths said they had used it in the last 30 days. Though O’Quinn and others question the accuracy of the study-some students admit that they deliberately exaggerated their responses-most agree that alcohol use is widespread.

“For a 14- to 16-year-old at Highland Park High School, it’s hard to come up with friends who don’t drink,” says Jordan.

Since taking over CAC last fall, Theodore has been rabble-rousing, “shaking some trees,” trying to galvanize the community over the widespread drinking among teens. “They don’t want to hear it,” says Theodore. “Alcohol is the parents’ drug of choice. They’ll talk all day about cocaine.”

But alcohol, of course, can be as deadly as any drug. Last November, HPHS basketball player Peter Ochel and 38 other kids were drinking beer near the railroad tracks running through a North Dallas field, playing a game they called “suction.” The kids were leaning back as a train rushed by. allowing the air flow to propel them forward. Peter was struck in the head by something protruding from the train. He lay in a coma for five weeks and is now in rehabilitation.

“There were 39 parents who didn’t know where their kids were, who they were with, or what they were doing,” Theodore says. He applauds a letter sent recently by a group of headmasters at area private schools urging an end to the unsupervised parties and better parental involvement. But he urges them to go further, identifying parents who are allowing their kids to throw parties at which alcohol is served.

Theodore thinks there is no such thing as teenagers “drinking responsibly.” It’s illegal, dangerous, and damaging to their still-forming brains. But there’s always the “squeaky few” with which to contend. “Usually in this community, those people are real powerful,” Theodore says. “They are used to having their own way.”

That was brought home vividly when he was discussing the new HPISD superintendent, John Connolly, with a powerful Park Cities man. “Connolly, smonnolly” the man said. “As far as I’m concerned, he’s just another employee, like my maid.” It was that kind of attitude that permeated a town meeting held three years ago to address the teen alcohol questions. Theodore says.

“They [school board officials] proposed that they were going to enforce the law, to go public and extend the consequences for use of drugs and alcohol,” Theodore says. “People were screaming and beating their fists.” One man challenged the board, saying that it was none of the school’s business if he wanted to have his son and six of his friends over for a keg. The proposal was approved, but never enforced.

Many Park Cities parents say they don’t approve of drinking for teenagers but understand that it’s a rite of passage, that no matter what they do, teenagers will drink. “It’s our impression,” says Jerry Smith, “that parents ’understand’ too much. They either ignore or tacitly accept alcohol use.”

Brito, at SMU, agrees: “I have parents say, Talk to me about real drugs, not alcohol.’ These kids think they are being responsible because they have designated drivers. That implies that the only casualties associated with drinking are those with driving.”

After the infamous party on Amherst, University Park Municipal Judge James Barklow required the students who were given MIPs (minor in possession citations) to take CAC’s “New Directions” course, a six-week seminar for first offenders. Parents of the other students who were too young to be cited were also asked to take the course; many did sign up.

Confronted with this get-tough approach, Park Cities parents are often angry and reluctant to participate. Theodore says. One father brought his 16-year-old into Theodore’s office, furious, complaining that he was not going to take the class. “I don’t have any time for this,” the man griped. “I don’t have any problem with him drinking. My kid is going to law school. He doesn’t need this on his record. Here’s the $100 course fee and a $500 check for the council. Sign us off.” Theodore refused.

Despite his protests, the father ended up getting a lot out of the class. Theodore thinks that the recent incidents may give impetus to a plan conceived at a “summit” of Park Cities educational leaders he called in January. “From [SMU President] Ken Pye on down, they committed themselves to providing a drug-and alcohol-abuse free environment.” Theodore says he, UP Police Chief Dixon, and Superintendent Connolly have banded together to resist parents who get “squeaky.”

Dixon has proposed a student-run club that could provide an alternative to private parties. Other kids are getting involved in programs like K-Life, a year-round program loosely affiliated with Camp Kanakuk, a Christian summer camp in Missouri that is very popular among Park Cities parents; some 185 of their kids go to the camp each year. At a cost of $730 for two weeks, kids get an infusion of values along with archery and swimming lessons.

Todd Wagner, the 27-year-old director of the Park Cities K-Life program, lives near the high school. Students such as David Harper, a top student, varsity basketball player, and next year’s quarterback, often come by after school or attend Bible studies and fun events on the weekend. “It’s comforting for us,” says his father, cardiologist John Harper, who has four kids. “We know they’re safe at the K-Life house.”

But Principal O’Quinn says it will take a communitywide effort to reduce the skyrocketing use of booze. “I don’t see people being prosecuted for selling alcohol to teenagers,” O’Quinn says. “I don’t see dads saying to sons, ’I don’t want you to drink. And because it’s so important to me, I won’t drink either.’ It won’t stop until the community decides it should stop.”

THE PARENTS WERE WORRIED; THEY made an appointment with psychologist Albritton to have their middle-school student evaluated. Was the problem drug use? Alcoholism? Running away? No. It seems their adolescent was not very outgoing, and was making Bs at school.

“I call it the curse of being average in the Park Cities,” says Albritton, whose clientele is almost exclusively from the area. “They’re normal, average kids. But their parents want them to be everything. It creates anxiety and depression. The expectations are sky-high.”

Jerry Smith agrees. “At-risk kids here are different than in other places,” he says. “They are average in looks, intelligence, athletic ability. But they think they’re failures.”

The process of creating talented, intelligent, accomplished offspring begins early. Park Cities children have schedules as rigorous as any adult: soccer, ballet, Japanese lessons, music and theater classes, art, tennis, science seminars.

“Here, kids don’t play,” says Randy Mayeux, pastor of Preston Road Church of Christ. “They have activities. I’ve never seen such competition for youths’ schedules. There’s more time spent on parenting in University Park than I’ve ever seen, but it’s structured time. Some kids would give anything to just play. But they don’t know how.”

The time crunch gets worse the older they get. When parents met at Mayeux’s church to discuss developing a youth program, some wanted a weekly meeting. All the Park Cities parents said that was too often; their kids had too much homework. “It makes it impossible to plan a youth ministry,” Mayeux says.

The better athletes are determined by the second or third grade, when parents pull the most promising kids out of the YMCA league and put them into Chamber soccer, which has better-trained coaches. Children’s sports take on a Lombardi ethic-winning is the only thing-that reaches ever new heights of absurdity. One Park Cities soccer coach complained because a girl with spina bifida on the opposing team was throwing in the ball from her wheelchair on the sidelines. An HPHS senior, who referees soccer games for the Y, says he’s had to tell over-involved parents to leave the field during games for 5- and 6-year-olds.

Academic pressure begins early, too. Margaret Arnold, a counselor at an HP elementary school, remembers the parents, both physicians, who called a conference with the teacher when their grade schooler’s 98 average dropped to a 93. “There’s a dramatic fear of failure in Park Cities,” says Arnold. “I see them push kids too hard, giving them gifts and games designed for older children. It’s the supermom and superdad syndrome: These parents put a lot of pressure on themselves.”

Smith says he has a male student whose father is putting such intense pressure on him, both in athletics and academics, that he can perform well in neither. One female student told him: “Mediocrity is not a word in our family’s vocabulary.” She was popular, talented, and pretty, but deeply frustrated because she was poor at math. Some kids, rather than competing, simply drop out-not physically, but mentally.

HPHS Principal O’Quinn says that the most difficult problems occur when parents’ expectations do not fit with their child’s abilities. “The hardest thing 1 deal with is a gentle, poetic child with a type A, self-made father,” O’Quinn says. “And the hurting child becomes a hurting adult. They wind up an alcoholic or a druggie.”

There’s a growing awareness among Park Cities students that rising to the level of their parents’ achievements may be difficult. “This is the first generation that may not live up to their parents1 success,” says Smith. “Is being a really good salesman enough?”

Schools are making changes to relieve the pressure. For example, Cecil Floyd, the principal at McCulloch Middle School, eliminated some honors classes and cheerleader competitions. Now, all eighth-grade girls are allowed to be cheerleaders; Floyd says the change has been very successful, though the elimination of competition made some mothers highly upset.

But many Park Cities parents seem to find a way-despite all the pressures, the distractions, the money-to cultivate kids who see themselves as special not because of their privileges, or what they achieve, but because of who they are. “I see a lot of really successful parents,” O’Quinn says. “They’ve got some kind of magic inside that family that tells the kids they are unique individuals. They find their strength and build on it.”

In response to the pressure, HPHS floated the idea of eliminating class rankings. Some parents are pulling their less academically oriented kids out of high-pressure private schools, where the problem can be even worse because students must meet certain criteria even to enroll. “They don’t get a sense of how really good they are,” says Liza Lee, headmistress of Hockaday. “All we can do is continually remind them that this is out of the reach of three-fourths of the world.”

One Park Cities mother says she was tremendously disappointed when her daughter asked if she could leave prestigious, highly competitive Hockaday four days into her junior year. The girl, now at HPHS, is blossoming. “She didn’t feel like she could survive without being appreciated for who she was rather than how she performed,” the mother says. “I felt if we could afford it, she should stick it out. I was wrong.”

Theodore is hopeful, but he’s aware that some things may never change. After the Amherst incident, CAC got more than 50 calls. Only one was negative. A mother whose senior daughter had been detained at the party was upset-not because her daughter had been drinking. She was mad because the girl, planning on entering college this fall, might not be able to get into the sorority of her choice.

For the last eight years, Mike Wallens has worked as a minister at a popular Park Cities church and its elementary school, St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church. But this summer, fed up, he’s leaving for another post. “I think this is not a healthy place for my boys to grow up,” he says. “Success here is measured by the car you have, where you live, how much money you have.”

Wallens says an all-powerful concern for appearance seems to spread over major decisions. (One mother of a sophomore marveled that-though 100 kids were detained at the Amherst party-no parents were talking about it.) Wallens watches as kids are handed cushy jobs with family friends instead of learning to fend for themselves, and he’s baffled by their attitude toward picking up after themselves. “After a lock-in at the church, I said, ’Let’s clean up.’ They said, ’What do you mean? That’s what Leon |the church maintenance man] is for.’”

With maids who clean up after them and parents who overprotect them, children growing up in the Park Cities could face a rude awakening in the real world, he says. But it’s not their fault. “I’ve never seen parents living so much through their children,” Wallens says.

Could the legendary involvement of Park Cities parents be too much? Do parents really need to be at high-school pep rallies? After all, a lot of growing up can only take place out of parents’ sight. “And in a neighborhood this small, that’s not easy,” says Prudence Mackintosh. “Surely part of the attraction of the unchaperoned party is escaping the ubiquitous parental audience with video cameras that has dogged these kids since birth.”

Everyone hears the horror stories-the spoiled kids, the overindulgent parents-but Mackintosh says she’s found her three sons’ friends to be a rather pleasant, wholesome bunch of kids. She points out that after the incident last year when the students chanted “white trash,” the school’s newspaper editor, Alexandra Guisinger, wrote intelligent editorials that made it clear blind prejudice was not to be tolerated.

“These kids do, however, get tired of being reminded how privileged they are,” Mackintosh says. “America loves those who overcome. Overcoming the lack of hurdles is the privileged kid’s challenge.”

Mackintosh does wonder about Bubble kids’ view of the world-whether they realize there are jobs out there that have nothing to do with law or medicine. And she’s also curious about their habit of group dating. While many parents applaud it-after all, few girls ever get pregnant on a group date-she wonders if it’s really a healthy way to learn about relationships.

If there’s one thing that Park Cities people say they cherish most about their childhood, it’s the lifelong friends they make. That’s one of the things Ann, now 24, remembers most about growing up here.

In fact, Ann thrived in the Park Cities. She didn’t mind the competition; she was involved in all the school activities. She knows that many of her friends would never live anywhere else.

But the Vanderbilt graduate, who now works as a claims adjustor in Atlanta, says she discovered an entirely new way of living when she moved to Georgia. Now she doesn’t worry about the image she projects, or wearing the “right” clothes, or where she fits on the economic scale. “I’m not a very pretentious person,” says Ann.

For all those reasons, Ann doesn’t planto return to her home town. She’s found,outside the Park Cities, the freedom andsense of self so many are seeking insideThe Bubble.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Commercial Real Estate

What’s Behind DFW’s Outpatient Building Squeeze?

High costs and high demand have tenants looking in increasingly creative places.

By Will Maddox

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 2

It's time to start worrying.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo