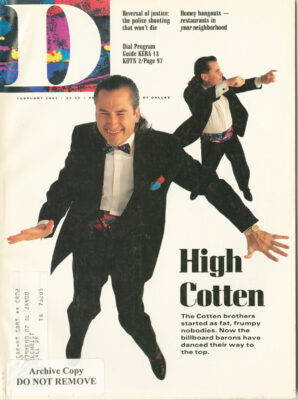

THEY LOOK MARVELOUS. DARLINGS.

Italian suits. Flowered socks. Moussed-to-the-max black hair. And those funky neon ties that serve, these days, as the flag of the sophisticated fun seeker. But it isn’t merely the appearance of the two brothers on the Mansion on Turtle Creek dance floor that is captivating the cocktail crowd. It’s the action. Wearing high-glossed, black crocodile and sea turtle shoes, they’re dancing the L’eggs off of two young women. A sultry cha-cha. A spicy swing. A dizzily spinning meringue.

“Damn, they’ve cleared the dance floor!” one astonished observer mumbles. Granted, it doesn’t take much to clear the floor at the Mansion, a bastion of tired fox trotters working off their lobster tacos by polishing the wife’s Chanel waist chains. But what’s happening tonight isn’t a dance; it’s a performance, a rite of arrival. Soon, every eye is upon them, the onlookers first staring, then glaring, then, finally, swearing, “Who the hell is that?”

The answer circulates faster than news of infidelity at a charity ball: “The Cotten Boys.”

“Who? A dance troupe? A rock group?”

“No, no. Michael and Stephen Cotten.”

Oh, yes. The Cotten Boys, rising stars of Dallas’s recuperating society. Eight years ago, Michael and Stephen Cotten were overweight, overwrought, damned near broke, and struggling through floundering marriages in the socially obscure burbs of Far North Dallas. Today, they’re thin, living high in midtown, and so sensationally single that The Dallas Morning News called them two of Dallas’s most eligible bachelors and Ultra, trumpeting 200 top Dallasites, listed them under “Great Moves: Not Just Flashy Dancers.” With Cinderella speed and Horatio Alger style, they roared into the spotlight while much of society was busy scuffling for a place to sit after the oil bust. Why did they do it? How did they do it? By understanding that to get anywhere in Dallas, you have to give. And by learning to dance.

THE COTTEN BOYS HAVE DALLAS surrounded. Their Billboards By The Day, the blue movie marquee-style billboards whose messages change daily, stare down on Dallas from 18 locations. A few days with the Cot-ten Boys prove that they’re as omnipresent, and as hard-selling, as their signs. What a life! They chat up the swells in the mansions of leisure, where stalwarts like Harriet Rose say, “I like what I see; they’re going places,” and Reuber Martinez, whom many con-sider Dallas society’s best dancer, concedes, ’It really shows that they love to dance.” Consummate gentlemen, they squire business baronesses, heiresses-in-training, and TV news anchorwomen like Channel 8’s Lisa McCree, changing their attire if they spot their dates sporting a clashing color on the 6 o’clock news the hour before their rendezvous, They pull up to the valet parkers at The Crescent in their cherry-red convertible, spraying twin blasts of lacquer-like hair spray, shooting their cuffs, and steering their killer grins into Stanley Korshak for yet another cocktail party, where socialites announce, “Hey, y’all, it’s the Cotten Boys!” They’ve even been known to break into a. rousing duet from The Music Man: “Yes, we got trouble, right here in River City, and that starts with . .”.

Today, we’re dining in a comparatively downscale working man’s restaurant. Enchilada’s on Greenville Avenue, (“BOOK YOUR CHRISTMAS PARTY AT ENCHILADA’S NOW!” screams a nearby Billboard By The Day.) The ever-coordinated Cotten Boys wear similar Mondo and St. Croix sweaters over black silk shirts and sip twin margaritas, served in snifters as big as fish bowls. On Fridays, a slow day in the billboard biz, this is their routine: lunch and a midafternoon movie, then a final stop by their headquarters, a tiny wood-paneled former used car lot office set between The Crescent and Rolex Building in the shade of a mammoth 12×44-foot Billboard By The Day. The office is so cramped with their six-person staff the Cottens don’t even have a desk of their own. But that’s okay. Most of the time they’re side-by-side in their car, meeting clients, doing deals by cellular phone, or pursuing their party-packed social schedule.

“It’s an incredible, incredible life,” laughs Michael Cotten.

“It’s great to be up in a down market,” adds Stephen.

This is how the Cotten Boys converse: One starts a statement, the other finishes it, speaking in a series of fractured sentences and half-thoughts. It’s a code they’ve had plenty of time to perfect. They not only work and play together, they live together-so close, says Stephen, “Michael can wiggle the corner of his mouth and I’ll know I have a crumb hanging off of mine.” Michael, 46, nine years older and four inches shorter than his baby brother, is the businessman, a shrewd master of finance and the art of hustling deals. Stephen, 37, is the artist and copywriter, dealing in concepts, poetic proclamations, and dreams. Together, they advance upon a goal that once seemed impossible: becoming a force in mainline business and social Dallas.

Today, they live on the seventh floor of the Terrace House, the favored rental pied-a-terre of movin’-up Dallas, well inside the LBJ Loop in a socially chic section of Maple Avenue. But to understand how far they’ve come, you must fust know where they started. The two sons of Joel and Mary Cot-ten grew up in a $17,000 frame house at 3564 Park Lane. Their father, an inventor, helped develop, among other things, the Dump Master Truck for Dempster Dumpster. Mother Mary, who now works as bookkeeper and assistant at Billboard By The Day, taught her sons “emotional strength and stability,” says Stephen.

Both brothers attended Thomas Jefferson High School, embarking upon similar paths of mediocrity. Teenager Michael threw the largest Dallas Morning News paper route in the city. He worked afternoons at Town North Hardware. He sold programs at T.J. football games. His first sight of Another Dallas came on the tennis court, where he competed on a team with Highland Park scions like Al Hill Jr. But when the swells skipped off to Terps, Mike went home to TV or his afternoon job. “I was kinda the smart nerd,” he laments.

Steve Cotten cut an equally pedestrian swath. He joined the debate team. He landed a background part in The Music Man. He worked as a parking attendant at Satellite Parking at Love Field. He was so ordinary that his lifelong friend, Dudley Slice, can’t recall one irregular action or incident. “We were average guys from average homes doing average things,” Stephen Cotter remembers.

They both attended North Texas State University. They both embraced the charismatic Baptist church. And they both married early-Mike at 24, Steve just barely 18-settling down for an average life of children (Michael has a 20-year-old daughter, Stephen a son, 12, and a daughter, 17), El Chico din-ners, and middle class occupations: Michael in car leasing, home building, and landscaping; Stephen in retail clothing, oil field equipment sales, and religious TV productions. Together, they taught Sunday school at Beverly Hills Baptist Church and had their own KPBC Christian radio program, Kingdom Principles with Mike and Steve Cotten.

“It was a study in how to be successful in today’s world by using God’s principle; give and it shall be given.” explains Michael.

“Sow a seed and reap a harvest,” adds Stephen.

In 1982, the ever-ordinary Cotten Boys, who claim to be devout believers in vows and commitments, did something quite extraordinary: They separated from their wives. Stephen left his first. “My youth made promises my marriage just couldn’t keep,” he explains. Six months later, Michael followed suit. “Insolvent financial times led to an insolvent marriage,” he says. Financially strapped, they moved into a one-bedroom North Dallas apartment, borrowed their dad’s 1976 GMC pickup, and began an economic scavenger hunt, buying, selling, and trading furiously in a dozen mediums.

Recalling those times, they offer old driver’s license and passport pictures taken just after their mutual divorces. The pictures show two obese, beaver-cheeked Cotten Boys, both weighing in at exactly 213 pounds. “The point is, when we moved out and started over, we left the girls and the families everything,” Michael says. “We left with only the clothes that fit us. I want you to know, weighing 213 pounds and all of a sudden being single? We really felt like big-time failures.”

He licks the salt from the rim of his glass, then takes a sip. “When 1 joined Steve, he’d had this little pity party goin’ for six months,” he says. “He was so traumatized he hadn’t even plugged in his refrigerator. It became easier when I joined him. But one night, sitting around in our T-shirts, talking, watching TV, we made a decision: ’No matter what, we’re not going to get jobs.’ Because we felt, if we got Monday-through-Friday jobs, we’d miss the million dollar opportunity. So we resolved ourselves to self-unemployment and searching.”

“We’d learned a lot from our past,” adds Stephen. “And we decided that, in our new lives, we didn’t want to be fat, poor, lacking in the social graces, and living out our lives in humdrum mediocrity.”

Their first step? Toning up their bloated bods. “We started at Goodbody’s,” says Michael. Stepping into the mirrored body-emporium, they discovered a brave new world of beautiful people. Longing to become a part of the scene-any scene!-they not only worked out with fierce discipline, they started power dieting with popcorn and Diet Cokes.

“We’d stop at a 7-Eleven in the middle of the day and buy microwave popcorn and Diet Cokes,” remembers Michael.

“We tried to eat popcorn at night, too,” says Stephen. “As best we could, we tried to eat popcorn. It was not so nutritious but very effective and cheap. We each dropped 30 pounds in six months.”

The new regimen sparked other improvements. “We began speaking formally, instead of informally,” says Stephen. “And we decided it was time to grow up and have grown-up names, instead of our shortened names.” So Mike and Steve became Michael and Stephen. They read inspirational books by statesmen like Bernard Baruch and articles about Dallas titans like Trammell Crow and Jimmy Ling. And because they couldn’t afford entirely new wardrobes, they spiced up their old suits with bright. Euro-flash ties, silk pocket squares, and new shoes, creating what one of their haberdashers, Abe Goldberg of L.O. Hammons, calls, “A very sophisticated West Coast-meets-Italian look, a very Bijan, Brioni look.”

Soon, the slimmed-down, smooth-talking brothers were ready to step into the night, As yet they had neither dates nor destinations. But on a trip to Acapulco, playing golf with the owner of a Boca Raton Arthur Murray Dance Studio, they discovered the quickest route into a woman’s arms; dancing lessons. “He invited us to the competition that night,” remembers Michael.

“We went and got sooo excited,” says Stephen. “Somebody said, ’Well you oughta have a good time at a party where there’s six straight guys, four hundred gay guys, and four hundred women.’ We came home and went straight to the Arthur Murray at Preston Center and signed up.”

“We were basically shy and, certainly, out of touch with dating, and dancing was a way to comfortably approach a woman,” adds Michael. “It was easier to meet someone with the question, ’Do you wanna dance?’ rather than the obligatory, ’Whaddya do?’” Before long, the Cotten Boys were good enough to enter dance contests . . . and win. Competing in the Arthur Murray International Dance Championship in Miami, they walked away with first prize in every novice division dance they entered. But no matter how many trophies they won, when they returned to Dallas they still considered themselves nobodies, searching for the million dollar deal.

A FTER LUNCH AND AN APROPOS movie-Mr. Destiny, about an ordinary man who wants more out of life than a nice home, a pretty wife, and a mundane existence- we head to the Cotten Boys’ apartment, where they dress for the evening. Emerging from twin bedrooms into a spacious, art-accented living area, they look, as always, perfectly coordinated with each other, even though they swear they don’t conspire on either wardrobe or hair styles (twin ponytails for avant-garde and casual events; slicked-back bobs cascading over their shoulders for cocktails and formal wear). Tonight, they wear pinstriped suits and ties with swirling shards of color, like the glass doors at Sfuz-zi. Stepping into his room, a haven of Perry Ellis zebra-skin sheets and framed party pics, Stephen begins reading aloud from a book of poems he’s written-the billboard baron as Baudelaire:

The future is out in front of us So we should ne’r lose sight Of what the promise holds for us When lives are steered aright.

This week has been laden with promise. They attended parties for Vice President Dan Quayle, Elizabeth Dole, and Bob Mosbacher. They traipsed through infinite disease dinners: a chili cook-off for leukemia, a fashion show luncheon for cystic fibrosis. Then there was the annual Gala for the Fort Worth Ballet, a fashion show for the Crystal Charity Ball . . . and that’s just a sampling. Three, four parties a night, that’s routine for the Cot-ten Boys. Why are they invited everywhere? Simply because they have something to give. But what could two brothers with neither trust funds nor pedigree offer Dallas Society?

The answer is Billboard By The Day. Its billboards not only promote charity events with a vengeance, they’re auctioned off as prizes at charity balls. How the Cotten Boys created this advertising tool-which, they say, has spawned a fully owned operation in Fort Worth, partnerships in Houston and Las Vegas, and copycat companies in Austin and San Antonio-is yet another chapter in their hard-driving brand of Hustle Economics.

“There is a business philosophy that really took Michael and I out of the doldrums and put us into the right frame of mind to succeed,” Stephen explains as we step out of the apartment, bound for Patrizio to meet a veritable Cotten Boy cult of friends, dance partners and members of their Power Jam aerobics class, before heading to their regular dance sessions at the Mansion. “We took the attitude of “What would you buy if we had it?’ When someone said, ’Well, I’d buy X,’ then, we’d go find X.”

Early on, they realized that the key to Dallas is connections. Airline tickets for corporations? The Cotten Boys could get ’em cheap. Gifts for radio promotions? The Cotten Boys would not only get the gifts, they’d design the promotion. But while their wild business scenarios multiplied, their money didn’t. Then, in 1984, they spotted something they wanted to buy: a dilapidated Braniff billboard on Mockingbird Lane at Love Field. Further research discovered that this prime billboard space was not only obsolete, the airline was in default on its lease. After negotiating with the leaseholder for the land, and trading Braniff $38,000 in credit they’d amassed on several billboards near D/FW in exchange for ownership of the Love Field space, the Cotten Boys went into the billboard business full time, leasing up new sign faces across town. “That deal changed our lives,” says Stephen. “The billboard paid off in less than four months. It became Muse, then Trans Star, and now it’s Southwest. It’s never had a vacant day.”

The Cotten Boys’ lifestyle improved apace with their billboard business. “We traded a billboard for the rent on a home,” says Michael. “Bent Wood Trail, a little north of Bent Tree.”

Today they say they own 51 conventional billboard faces on leased land throughout the Metroplex, not counting their Billboards By The Day. But shortly after they began, new city and county restrictions on billboard zoning and placement threatened to shut them down. “Our business was almost capped,” says Stephen.

In 1987, they took their troubles on a four-day Las Vegas vacation. By the third day, their gambling allowance depleted, they were standing in front of the Las Vegas Hilton, looking for something to do, when their future flashed in front of their Ray-Bans. “We were watching the man at the Hilton changing the marquee,” Stephen remembers. “We knew the science of billboards: how large letters have to be to be read at a certain speed, and that anything below a 12-inch letter is worthless. So we thought marquee letters were all 12 inches or smaller. But this man is up there taking letters off the marquee of the Las Vegas Hilton and some of them are twice as big as he is.”

Watching the little man on the big sign, Michael Cotten realized that he and his brother had finally stumbled onto the million dollar deal. “Stephen, if we put those letters on our billboards, we’d have a radio station on the ground,” he said. After six months of research, they bought equipment and hired someone to change out billboard messages from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. daily, confident that they were about to unleash the future of outdoor advertising. (The price for an entire billboard, on which one can say anything from MICHELE, OUR LOVE IS INCREDIBLE! WILL YOU MARRY ME? to WE LOVE NUTRI-SYSTEMS!, is $300 a day Monday through Friday, $200 on Saturday, and $150 on Sunday. No X-rated or malicious messages are accepted.)

“This is not billboard advertising, it’s an outdoor broadcasting system,” Michael explains. “On an institutional or subliminal billboard, you have to say things that are image-building and last from six months to a year. On our billboards, you can say, ’Get your tickets tonight!’ You can advertise, ’First day, second day, last day.’ “

“The first Billboard By The Day was over the Tollway at Maple,” Stephen says. “KLUV Radio was the first advertiser. It was the LUV-Wish Contest.”

“I think it said. ’Win $100,000,’ ” says Michael.

“The first billboard sold out the first month.” says Stephen.

“But our second, third, and fourth billboards. . .,” says Michael.

“Were much more difficult,” says Stephen.

“It maybe sold six days a month,” says Michael. “And then it became like anything else. It was not a bird’s nest on the ground. It took a lot of work. And we had a big problem: Nobody was taking us seriously, nobody would see us. Frito-Lay and Dr Pepper and all the others would say, ’I’m sorry, we don’t have a line in our budget for Billboard By The Day.’ None of the people who mattered would even let us in to talk to them about our product.”

To get inside, they needed an introduction. And the introduction arrived on the heels of their dancing.

A FTER AN HOUR OP COCKTAIL CON-versation at Patrizio, the Cotten Boys synchronize their watches. (Michael gifted Stephen with his $7,000 Baum & Mercier; Stephen, in turn, one-upped Michael by giving him a diamond-faced Concorde.) Michael advises his brother that he’ll check out the Mansion Bar and “beep” him over their communal pager. During their rare moments apart, the Cotten Boys are always in communication this way, one forging ahead like an Indian scout, the other remaining with the original party, then moving on to reunite once a new stronghold is established. In tonight’s case, Stephen seats his 20-person Power Jam aerobics class at a long table for dinner, then cools his $700 Bruno Magli crocodile loafers beside more friends at the bar. When his beeper still hasn’t sounded by 9:30, he decides to move on anyway.

In the Mansion Bar, Michael Cotten sits in front of the filigreed fireplace, amid the forest green walls, flying geese, deer antlers, and middle-aged craziness, recalling the moment that jolted him and his brother out of social obscurity. It happened in Profiles, the now-defunct Oak Lawn dance club and early Cotten Boy hangout. One enchanted evening, Michael was sipping his Chivas and soda on the sidelines, admittedly a little smug, having just cha-cha’d the socks off of one of his regular partners, when a waitress brought over a note. “My date doesn’t dance,” it read. “Would you like to dance with me?” He stared across the dance floor and saw an incredible apparition smiling back. One word flashed into his brain . . . WOW. The big black eyes. The perfect body. The 100-watt sequins. The steel magnolia countenance. Good God, it was super realtor Carolyn Shamis!

Today, the Cotten Boys divide their lives between two eons: Pre-Carolyn and Post-Carolyn. But in the beginning, Michael Cotten knew nothing of Carolyn Shamis’s local feme, which includes a long, fabled line of Excalibur automobiles and zillionaire clients. “All I knew was that she was a lovely lady,” he remembers. “When her date went to the men’s room, I hotfooted it over and asked her to dance.”

“Dancin’s like a drug to me; I just have to git it,” Carolyn Shamis says. She has arrived in the Mansion Bar, as usual in black sequins and with infectious energy, to dance with Michael to the seductive society sounds of the Tony Sheppard Trio. “I was hungry to dance like Michael danced. Hungry! The night I met him, I wanted to dance so bad that I asked my date, who didn’t dance, to just stand on the dance floor and let me dance around him. I mean, Michael was just truly leading. So few men know how to lead; I always have to lead them. But he led me. And it was beautiful.”

Michael Cotten and Carolyn Shamis began dancing together every Thursday night after that first meeting, becoming fast friends and such celebrated partners that they were later asked to dance in exhibition before a Louisiana party audience and at a “Waltz Through the 90s” party for the Dallas Opera.

Not long after they met, Carolyn asked her new friend to make dinner reservations on a Saturday night at the Mansion, an establishment Michael had never visited before. When he called the Mansion for the reservation. Michael was told, respectfully, to forget it; Saturday night had been booked up for weeks. “I called Carolyn and told her we’d have to think about a different restaurant,” Michael remembers. “And she said, ’Call again and ask for [maitre’d] Wayne Broadwell. Tell him you’re coming with Carolyn Shamis and you’d really appreciate it if he could figure a way to squeeze you in.’ And it was like magic. I did, Wayne did, and we walked in that night and they sat us at banquette No. 2, one of the best tables in the house. Before that, I didn’t really realize how celebrated Carolyn is. I mean, the world stopped.”

“We not only didn’t know that you weren’t supposed to sit out in the Atrium,” adds Stephen. “We didn’t even know there was an Atrium. Wasn’t John Tower there that night, Michael?”

“John Tower was there, George and Sarah Pavey were there, the plastic surgeon Sam Hamra was there,” Michael says. “And the very idea that John Tower, or any of the other people who are famous in this town, would be in the same room with me was just unheard of. But that night, I mean, everybody stopped by to say hello to Carolyn.”

Soon, Michael Cotten was saying hello back. On Carolyn Shamis’s arm, he became a regular on the charity ball circuit. But in the beginning, nobody knew his name. “The first two or three times I was in the paper, it always said, ’Carolyn Shamis and Date,’ ” he remembers. “At the Great Gatsby Ball a couple of years ago, they took our picture and wrote, ’Carolyn Shamis and Date Win Dance Contest.’ “

But as the word spread of the billboard space the Cotten Boys had to offer, their phone started ringing with charitable solicitations. The ever-cerebral Stephen Cotten calls their willingness to give “The Seed Principle” of their social and business success. But it is basically the same Kingdom Principle they once preached on Christian radio: Give and it shall be given. “We believed that if we planted the seed, it would grow up and bear fruit,” Stephen says. “We planted the seed by giving the billboards for charities, both for their auctions and to promote the events. And in planting that seed in their cause, meeting their need, the tree grew up and met our needs.”

What was their need? To get inside the closed doors of Power Dallas. “We said, ’Since nobody will see us, and all these charity women are calling us, and she’s the wife of the vice president of this and that, well…’ ” says Michael. “After awhile, we said, ’Yes, we’ll give the billboards and, by the way, we’d love to meet your husbands.’ “

“What would happen is the women would call and say, ’We would like to advertise our event on your billboards,’ ” Stephen explains. “And we’d ask, ’What are your sponsorship packages?’ And they would say, ’Well, for $1,000, for $2,000, for $4,000, you get . . .” We would simply become a sponsor.”

Very quickly, they were receiving seven, eight charity requests per week. And, because sponsorships for most events include tickets or tables for parties, the Cotten Boys were soon attending practically every charity luncheon, cocktail party, and gala in town. How could they afford to devote so many billboards to charity? Because Billboard By The Day always has surplus space. Of the company’s potential 1990 sales of $1.65 million, the Cottens estimate that $800,000 will be actual revenues, $350,000 will be given away as bonuses to clients, and $500,000 will go to charities as donations.

“Most people work society to take,” says Michael. “We want to give.”

“Give and it shall be given,” says Stephen.

“They’re certainly on my A-list, always more than gracious to support the cause,” says Roz Campisi, who has enlisted her friends the Cotten Boys’ support in all five of her Multiple Sclerosis charity events, not including the also Cotten-supported Yellow Rose Gala. “What’s so great about them is, if it’s a good cause, they wanna be involved. They’ll buy tickets. They’ll buy tables. They’ll put up billboards.”

Where the charities went, businesses soon followed. Neiman Marcus, Avis, Leadership Ford, Taco Bell, The Dallas Morning News, Channels 5, 8. and 21 . . . these are but a few of the corporations that have flashed timely, temporary messages before the city on Billboard By The Day.

On March 11, 1989, the Cotten Boys were well on their way to reaping. So, deciding it was time to give, they hosted a gala on their own. “The debutante ball, social introduction of Billboard By The Day,” Stephen calls it. Donating $50,000 worth of billboard space for the Ramses the Great exhibit at Fair Park, Billboard By The Day became a $50,000 Arts Sponsor, entitled to a private showing for 100 guests during Ramses’ opening week. The Cotten Boys paid for an extra 87 tickets and invited 187 friends. clients, and charity connections to a pre-party at Profiles. The club’s cardboard-sphinx decor paled, however, compared to the profiles of Michael and Stephen Cotten. It wasn’t merely Goodbody’s, Arthur Murray, and the glow of inner-city success that made both brothers look 10 years younger; it was the hands of Dr. Edward P. Melmed, a plastic surgeon who lifted what Michael Cotten calls the “Louis Vuitton” bags that once hung below the brothers’ eyes.

“I feel like Horatio Alger” Stephen Cotten says. “Because Daddy grew up on Mexican Hill in Big Spring, Texas, and stole his school books to go to college. And here we are, boys who grew up in a $17,000 frame home, and yet by the grace of God here we are enjoying the finer things in life.”

The finer things have rained down upon them this evening. Back in the Mansion Bar. they’ve just come from a red-letter event; their first movie premiere. Hoping to persuade West Coast film marketers to advertise movie openings on Billboard By The Day (“They can say, ’”Batman” Starts Tomorrow,’ then on Friday, ’ “Batman” Starts Today!’” exclaims Michael), they offered Castle Rock Entertainment billboard space for a movie premiere to demonstrate how they and their billboards can draw a strong Dallas crowd. The movie they premiered is once again apropos: “Sibling Rivalry.” Circulating invitations all week in frenzy, the Cotten Boys merely wanted to meet the Castle Rock PR company’s expectations of filling a 300-seat theater at the UA Plaza. But tonight they dazzled ’em with a crowd of 570.

“With one-half of 1 percent of their advertising budget, the movie could buy every billboard we have in every market!” says Stephen.

“I mean, we’re a movie marquee!” says Michael.

Beside the boys at the bar, a mainline society playboy is sneering, miffed because, tonight, the Mansion Bar seems filled with a new crowd of social unknowns. “I used to ! know everybody in the Mansion, but I don’t know 90 percent of these people!” he complains, mocking a party girl wearing an Alexis Carrington hat and a roughneck in a Kuppenheimer two-fer suit. Soon, he’s staring at the Cotten Boys. Who do you think they are, he asks, with their big grins, hair pomade, and blue-and-gold, marquee-embossed business cards? “The height of faux silk,” he laughs. Yes, there will always be those who arrived first and disdain all who come afterward, and the Cotten Boys have as many fierce detractors-in both Dallas business and society-as they do rabid fans. But tonight, only compliments reach the Cotten Boys’ ears. “There’s nobody as classy, as continental, as much a signature of Dallas as these two,” says Ad-dison real estate developer Jim Miller.

Ah, but there is . . . and they’re promenading into the Mansion Bar now: a group of old-guard, oil-fed Dallasites, fresh from a charity ball in perfect tuxes and taffeta. They appear so grand amid the jungle commotion of the new crowd. Yet, like most of Dallas society, they’re just one generation removed from roughnecked ancestry themselves.

As the new arrivals stroll toward a reserved center table, the bar’s conversation pauses, then accelerates, everyone genuflecting and scanning mental Rolodexes for names, titles, net worths. The charity bailers sit, like the last of the cowboys surrounded by heathen Indians, looking around in shock, as if to say, ” Who are these people?”

Despite how far the Cotten Boys have come, it will take them quite a while to make the journey from the bar to the old money table, from barely arrived to truly inside, a few steps by foot, a giant leap in social cachet.

“We will never be old guard,” says Michael Cotten,

“Yeah,” says Stephen. “But maybe our children will.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain

Things to Do in Dallas

Things To Do in Dallas This Weekend

How to enjoy local arts, music, culture, food, fitness, and more all week long in Dallas.

By Bethany Erickson and Zoe Roberts

Local News

Mayor Eric Johnson’s Revisionist History

In February, several of the mayor's colleagues cited the fractured relationship between City Manager T.C. Broadnax and Johnson as a reason for the city's chief executive to resign. The mayor is now peddling a different narrative.