When Kevin Murray played his last down as the star quarterback of North Dallas High School, he-like too many others who are quick of mind but quicker of feet-knew he could cash in on his athletic prowess. He signed a letter of intent to play at Texas A&M, but instead made $35, 000 playing minor-league baseball for a year. Then, after a court released him from his contract with the baseball team, he headed for A&M.

When Kevin Murray played his last down as the star quarterback of North Dallas High School, he-like too many others who are quick of mind but quicker of feet-knew he could cash in on his athletic prowess. He signed a letter of intent to play at Texas A&M, but instead made $35, 000 playing minor-league baseball for a year. Then, after a court released him from his contract with the baseball team, he headed for A&M.Murray didn’t decide to forsake a paying job for the often intangible betterment that education can bring; he came for the money. And A&M was thrilled to have him.

Kevin Murray went to class enough to stay eligible, yes. But the main thing he did was play football, and play it well, leading the Aggies to two consecutive Cotton Bowls. Court testimony shows that Murray, in turn, was nicely paid, in cash and cars, for his services. But before his senior year arrived, and well before he was due to graduate, Murray found himself more than $25, 000 in debt to a Dallas sports agent and in need of more money than the relatively pristine environment of a major state university would provide. Clearly it was time for the next gig. So Murray left school a year early, heading for stardom and riches in the NFL.

His pro career, however, never materialized. He failed a physical because of a bad ankle and never played a game of professional ball. And things got worse from there. Murray’s agent, Sherwood Blount Jr. of Dallas (banned from contact with SMU because of his part in the university’s pay-for-play scandal), took Murray to court to collect. The A&M football program, because of Murray and those who recruited and paid him, received two years probation, which meant the loss of thousands in potential TV and bowl game revenues. The school also wasted a scholarship on a young man who wanted nothing a college could provide except a job playing football-this at a university that turns away almost 2, 000 applicants a year who don’t meet the academic standards.

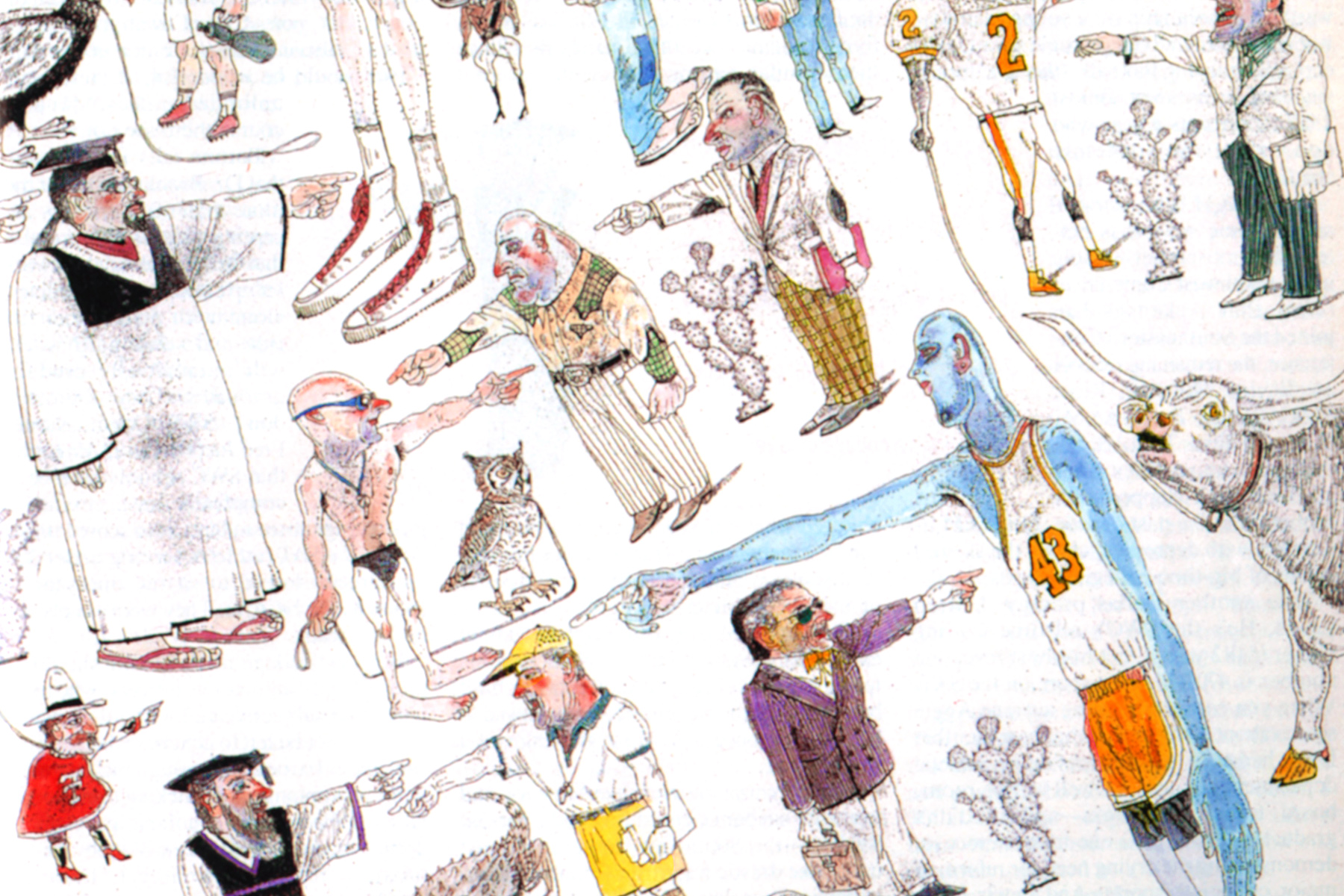

Texas A&M is no worse- and in some ways it is better-than most other schools in the Southwest Conference. (Now that Arkansas has joined the Southeastern Conference, the remaining schools are Baylor, Houston, Rice, SMU, Texas. Texas A&M, TCU, and Texas Tech. ) Six of those nine universities, after all, have been slapped with probation in the past decade. But A&M illustrates with depressing clarity the skewed values of big-time collegiate sports.

Take another Dallas prodigy, Darren Lewis. He’s the SWC’s all-time leading rusher (5, 012 yards), but his most revealing number is 470-his first score on the SAT. When you consider that the average Aggie scores about 1040, and further consider that Lewis had every advantage of tutors, athletic department advisers, as well as free room, board, tuition, and books-and still didn’t graduate-you’ve got a one-man microcosm demonstrating the crying need for reform of major collegiate sports. And Lewis is far from alone: According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, barely 30 percent of the SWC’s football and basketball players have graduated during the past five years.

Despite tutors, free room and board, and other perks, fewer than 33 percent of SWC football players are 24 percent of basketball players ever get a college degree.

“Reform, ” of course, is a relative term. Would-be reformers have been issuing reports and manifestoes since the Carnegie Report (Andrew, not Dale) called for reform in 1929. Their prescriptions for curing college sports have ranged from cutting a few scholarships here and there (still enough to give many a coach heartburn) to the harsh medicine dished out by Rick Telander, a senior writer at Sports Illustrated who argues that real reform means ending the oxymoron known as the “student-athlete” by eliminating collegiate teams altogether and developing a semi-pro league.

We shudder, Those empty stadiums… those empty Saturday afternoons… no bowl games? No, there’s got to be a way to reform major college sports without throwing the baby out with the Gatorade. But unfortunately, the reforms being discussed within the SWC and the NCAA will not solve these inherent problems of big-time college athletics. Ideas like making athletic purity a requirement for university accreditation or making all schools release graduation rates for athletes are worthwhile suggestions, but in reality they would do nothing to correct a corrupt system. In fact, the reforms suggested by committees, university presidents, and legislators are, at best, minor procedural changes, most of which have been discussed in the SWC since college football began in Texas 100 years ago. (In fact, the reason the conference was formed in 1915 was to enforce academic and ethical standards. ) Since then, similar reform movements have not changed what is now a system designed and run by coaches and former coaches to make themselves wealthy, usually at the expense of a student-athlete.

That is why Murray had no qualms about exploiting a system that so often exploits fellow athletes. Still, he should never have been accepted by a university and allowed to fill, at least once in a while, the chair of a real student.

To avoid more mistakes like Murray-and to ensure academic credibility and financial stability-the Southwest Conference must undertake drastic reforms affecting athletes, budgeting, coaches, TV and marketing, and institutional integrity. Here’s how:

“Student-Athletes”

The Problem: Fewer than 33 percent of SWC football players and 24 percent of basketball players ever get a college degree, according to the Chronicle. Of those that do, huge numbers don’t get a meaningful education that will serve them if they fail to make the pros.

Flashback: “I believe that many students go to college with no real ambition to become college graduates, yet when rules are enforced that they cannot play in games unless they maintain certain standards… many of them are led to graduate. ” -Dr. S. P. Brooks, Baylor president, 1928.

Coaches’ Party Line: “The picture of poor, abused athletes being taken advantage of is a complete misconception. ” —R. C. Slocum, Texas A&M football coach.

The Solution: Ban coaches from having a hand in the academic process by no longer allowing them to lobby admissions departments on behalf of athletes, act as an athlete’s academic adviser, dictate class times or class selection to athletes, monitor study halls, etc. Admit only college-ready students, then test them upon graduation to determine if they received basic college-level skills.

Coaches should have no say in the multilayered academic process because most don’t understand the role of a university in our society. “Every kid that wants a chance should be able to go to college, ” argues Tony Barone, Texas A&M basketball coach. But, notes Chris Cowan, co-director of the National Values Center in Denton, “That would be wonderful, if there were unlimited niches. ” And of course there are not.

Barone falls into the trap that Dr. Brooks of Baylor did more than 60 years ago, accepting kids on the premise that the huge tutorial network set up exclusively for athletes, along with a full financial ride and some hard work, will miraculously produce graduates. They obviously don’t. SWC Commissioner Fred Jacoby told D Magazine that SWC schools have been completely unsuccessful in graduating those students who scored under 700 on the SAT (athletes scoring under 700 are already forced to sit out one year of sports by the NCAA). They were simply not college-ready.

What is “college-ready”? That should be up to schools’ admissions officers, who must make that subjective call with all students. It should not be left to coaches who are worried about harnessing enough big horses to win a championship. In picking the students who will be awarded scholarships, coaches decide which students they will lobby the admissions department to accept. Too often coaches recruit athletes with well-below-average test scores, very low high-school GPAs, and little academic desire. We’re not talking “marginal admits. ” If students were educated in a substandard ghetto or rural school system, but show an aptitude for learning not reflected on SAT scores, universities rightly take that into consideration. We mean the 30 out of 120 high-school graduates who were at last year’s Nike all-star basketball camp who could not even read at a sixth-grade level. Ten were functionally illiterate. Many of these students would be better suited for remedial or vocational education. (There’s no shame in not going to a four-year college-almost 70 percent of high-school graduates don’t. )

Coaches argue that any type of schooling is good for kids who are poor and have little hope of paying for college-in athletics, they usually mean black students. The problem is that the schools don’t overcome the barriers to a black athlete’s chances of graduating. The NCAA reported in July that only 25 percent of black football and basketball players who entered school in 1984 or 1985 graduated, while more than 50 percent of white athletes got their degree.

Even if an athlete should be accepted, remember that college athletes who graduate often don’t get a meaningful education from the school that makes millions off their talents. Vague conference and NCAA rules allow athletes to “stay eligible” while barely maintaining a C average. They can even flunk all courses in the off-season, yet play every game the next semester.

The athletic department tries to help ill-prepared students by providing tutors and other academic crutches that, ironically, can interfere in the students’ academic development. Tutors often take notes for athletes and walk them to class. Athletes are routinely steered to easy courses. One Midwestern school reportedly has run mainframe computer searches to locate those teachers who have traditionally been easy on athletes. One SWC coach even says he’s heard of coaches telling professors who had flunked athletes, “You just cost your school a million dollars. “

In light of all this, the only way to see if student-athletes have received basic college skills is the same way we see if they have received basic high-school skills: Test them. Have athletes take the Graduate Record Exam upon graduation and publish those average scores for a school’s athletes without naming them. (Naming students is unnecessary and would violate a set of federal laws known as the Buckley Amendments. ) Bonuses and incentives could be given to coaches who recruited students that proved themselves worthy, but since coaches are not responsible for the students’ education, no penalty except public humiliation-for the school and the coach-would be necessary should students fail to measure up.

Budgeting

The Problem: Athletic departments lose millions of dollars annually. Athletic department personnel think the only way to correct this is to win more games, ignoring the fact that even the most competitive programs lose millions. This winning-equals-balanced-budget philosophy encourages coaches to see athletes as hired help, not as students.

Flashback: In 1918, SWC revenue was $180. 30, while costs were $192. 38. The secretary-treasurer attached a note to the annual report that said, “The Southwest Conference owes me $12. 08. “

Coaches’ Party Line: The football and basketball programs have to make enough money to support all the non-revenue-producing sports.

The Solution: Drastically cut costs to balance budgets, ending the perceived relationship between athletic performance and balanced budgets. Also, have the university fund the athletic department as it does all other departments instead of letting it act as an autonomous entity. Both the department and the university will thereby be made more accountable.

The problem is not new. A 1962 headline in Fortune magazine said, “College football has become a losing business. ” That was when attendance was soaring. Now, almost every athletic department in the U. S. runs in the red by normal bookkeeping standards. Athletic directors and coaches think the only way to change that is to spend more money, building big, new stadiums and training facilities and making everything first-class to impress recruits, etc. From 1985 to 1989, spending increased 47 percent in college sports (probably a low number, as it’s based on volunteered information). Revenues have risen slightly in the SWC and college sports in the past decade, but not nearly at the rate of costs. Now attendance has leveled off, and revenue increases are also unreliable-dependent on variables such as won-lost records, fan attendance, and actual instead of projected payouts.

But costs are easy to cut. First, cut football squads to 50 players instead of 95; after all, the pros get by with 45 per team. That saves the school from absorbing the tuition, room, and board expenses of those additional 45. A school like SMU, for example, would save more than half a million dollars a year-and it would make that much in addition if paying students took those slots in the university. Although it could be argued that this would eliminate some opportunity for those good students who want the experience of being on the team, even third or fourth string, the money is not there for this luxury. And coaches themselves have complained that too many players who are not good enough to see much, if any, game time don’t take school seriously because they really think they can still make it in the pros. The SWC should help end their delusions. Also, other students suffer when too many scholarships are given by an athletic department that can’t pay its bills. At many schools, up to 80 percent of student fees are funneled to the athletic department to help cover costs.

Next, slice travel and recruiting expenses in half. Murray Sperber, in his exhaustive study of collegiate athletic finances, College Sports Inc., estimates that the average big-time football program spends $1 million a year on travel and recruiting. It’s not unusual for a guaranteed check for a road game, or a big payoff for a bowl game, to end up a deficit because the athletic department turns each trip into a soiree for athletes and booster hangers-on. Stop giving recruits the red-carpet treatment-fine hotels, nice restaurants (SMU. for example, had been taking recruits to Reunion Tower for dinner, but they didn’t see the campus library).

Then, slice coaches’ salaries by at least half. Former A&M football coach Jackie Sherrill’s annual base salary was more than $600, 000, with perks pushing a year’s take to over $1 million. (Of course, this sweet deal was offered by Bum Bright and the Aggies booster club before the president or athletic director knew about it-but that’s another problem entirely. ) Such absurd excesses are the exception, but the average coach still makes around $100, 000 a year, while the many minions known as assistants come in at about $70, 000. Tenured faculty members teaching history, English, and economics at the same institutions would do well to pull down $45, 000.

The average SWC coach makes at least $100,000 a year. Tenured faculty in English economics, and history do well to put down $45,000.

But salary only makes up about a fourth of a coach’s income. For example, Texas basketball coach Tom Penders’s reported base salary of $105, 000 is significantly augmented by a shoe contract, a TV show contract, and huge profits from summer basketball camps. The total package comes to $400. 000-but that doesn’t include another $75, 000 in perks and potential bonuses; nor does it count a $60, 000 a year supplement to his salary taken from the interest of a $1 million endowment supplied by a UT alumnus.

Now. there is nothing inherently wrong with earning a large salary (or so we’ve heard). The problem is that those lavish incomes are all contingent on winning. The contracts and incentives and perks are provided if a coach’s team remains successful. Because we’re talking about so much money, there’s huge pressure on a coach to win just to maintain his lifestyle and pay his bills. That pressure causes coaches to put their interests ahead of the students’ or universities’. The athletes, who (supposedly) earn no income for their efforts, know that their ability to slam in the game winner with two seconds left keeps Mrs. Coach in mink coats. Some observers believe we could see players boycott games for payment in the near future, but even barring that nightmare, it’s arguable that the big-bucks syndrome tempts players like Murray to take under-the-table cash: Why should Coach get the goodies while we lake the hits? And faculty resent the signal that their university sends when it pays a respected, tenured professor one-third what it pays someone who’s pretty good at chalk talk and waving a clipboard on fourth and long.

Because all this money usually comes as a result of a university’s recruitment of certain talented athletes, and not because Coach X just happens to be a nice guy, universities should handle all outside contractual agreements with shoe companies, TV producers, etc. The universities would then keep a substantial percentage of the profits to put back into the athletic department and dent the deficit, thus relieving some of the endless pressure on the coaches to win. This way, coaches are insulated; when a shoe sponsor grows dissatisfied with a team’s won-lost record, it won’t affect the coach’s pocket-book significantly. It would also bring athletic department finances more in line with those of other departments within the university. When an English department holds a literary festival, for example, proceeds go back to the department, not toward a professor’s 27th payment on a Jag.

Oh, yeah, the other budgeting complaint. “Somebody has to pay for the women’s programs, ” says University of Houston athletic director Rudy Davalos. Yes, and because Title IX legislation requires equitable funding for women’s sports, the painful act of spending big bucks on low-profile events that return little money to the coffers must continue. But as D shows, it can be done. And don’t forget that the NCAA forced women’s programs to become members years ago, when women’s programs were running themselves and were profitable. Any current problems were brought on by arrogant men who refused to allow women to run their own show.

The Coaches

The Problem: There is too much institutional pressure on coaches to win; therefore they justify unethical behavior that enables them to land star athletes-regardless of the athletes’ academic ability.

Flashback: “Any coach would exchange his so-called exorbitant salary for… a reasonable professional salary with a guaranteed tenure of office during good behavior” —Dr. D. A. Penick. SWC president, 1926.

Coaches’ Party Line: “Hell, yes!”

The Solution: Mandate five- and 10-year contracts for coaches.

Coaches are often smart and friendly, usually hard working, and always asked to produce the nearly impossible. A coach must at once be a sharp tactician, sage to the stars, model citizen, and successful businessman. But most of all, he must win. Even though most coaches don’t get fired (they resign and take more lucrative positions), those who are fired are most often axed for not winning. As Houston’s Pat Foster points out, even at Texas Tech. where President Robert Lawless is a leader of the academic reform movement, Gerald Myers was fired as basketball coach this year for not winning enough games. Is it any wonder coaches would rather take sculpted gladiators over capable students?

To remove the pressure to win at any cost, all coaches need to be given job security, as was recommended by the Knight Commission, which issued its own general reform recommendations in March. But SMU athletic director Forrest Gregg says that alone won’t work. “For any coach that’s worth a nickel, it wouldn’t take the pressure off that he puts on himself-and that’s just the nature of the beast. The greatest pressure that comes to a coach comes from himself. ” Universities can’t do anything about that, save pay for therapy sessions. But they can at least stop coaches from arguing that they are worth their exorbitant salaries-and justifying unethical behavior-because of institutional pressures.

“Why can’t coaches get tenure?” Gregg then asks. The short answer is that tenure was developed for academics, where standards of achievement are entirely different, and where professors who explore unpopular ideas need protection. Coaches, who are hired tor a specific performance, sign contracts. A reasonable compromise would be to make al! contracts five-year or 10-year deals. In these contracts schools would specify that coaches will not be fired before the contract is up because of the team’s won-lost record; only serious violations of school or NCAA policy would be grounds for dismissal.

Coaches currently disregard what is best for student-athletes (winking, for example, at unethical behavior like having tutors do a jock’s work for him) because they are concerned with job security. However, if keeping their jobs were tied to putting student-athletes’ concerns ahead of their own, then coaches would be more likely to do so. Let them deal with self-induced. Type A pressure themselves, without the school footing the bill.

TV and Marketing

The Problem: TV worship. Believing that being on TV cures all recruiting and budgeting woes, coaches and athletic directors disregard what is best for the student or school if it means a better TV deal.

Flashback: “In 1951, a majority of the NCAA membership, convinced that televising college football had to be limited, passed the NCAA’s first TV rule: one national game a week on television. ” -Murray Sperber, College Sports Inc.

Coaches’ Party Line: Houston basketball coach Pat Foster says it best: “It’s entertainment to the public. You can’t separate college sports from pro, because TV has changed all that. “

The Solution: Colleges should quit trying to win games, change conferences, sign scheduling agreements, and generally bend over backward to placate the TV networks. Instead, the schools should spend that energy in a multimedia campaign that markets an SWC image that stresses academics first, athletics second.

Television contracts have been regarded as the panacea for college athletics for almost a decade now, yet the shades of budget-red just get deeper. TV pots of gold make up only about 10 percent of SWC budgets, yet the lure of a 19-inch showcase for the fans on a Saturday afternoon-or morning, or night, or whenever the networks demand-caused the University of Arkansas to leave the SWC after 76 years. They became one of a number of big-lime schools that switched or contemplated switching conferences to get into what was optimistically called a “superconference”-a huge group of schools in separate but large and influential TV markets that band together and then take larger pieces of the TV pie. Arkansas*s defection hurt the SWC, but the pain was mostly felt in pride. The percentage of TV households in the remaining SWC schools’ area dropped just one point, to 6 percent of the national total.

TV is not going to save free-spending athletic departments now any more than it has in the past. In 1984, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Oklahoma and Georgia universities, agreeing that the NCAA was limiting the ability of big-time programs to be on TV. Until that time, the NCAA negotiated all the schools’ TV contracts, designating a limited number of games for TV in order to keep viewers hungry for more. When the court said that setting limits on the number of televised games limited schools’ incomes, big-time programs like OU and Georgia thought they’d get rich with more TV money. But with too many televised games for the number of fans who cared to watch, big schools made only half as much money from TV as they did before, while smaller schools got nothing.

Looking to TV as savior makes even less sense in today’s environment with problems that include a recession, fewer advertisers, an ongoing TV game glut, networks like CBS losing hundreds of millions on sports programming, and a potential court ruling next month giving schools even more leeway when TV contracts are restructured in 1993. “People are dreaming if they think a super-conference will trigger a dramatic increase in rights money, ” TV sports consultant Jim Spence told The Wall Street Journal.

The SWC is already approaching its TV deals in the correct frame of mind. Commissioner Jacoby understands better than the folks at UT and A&M that regional deals, while less prestigious and lucrative than network contracts, are a surer source of income. The SWC recently more than doubled its contract with the regional sports network Raycom, Inc., from $1. 4 million to $3 million. If SWC teams win more, they become more attractive to networks, and bring in more money.

Colleges should undergo an audit every year. If improprieties are found, suspend the school fr one to five years.

But schools can’t count on that, so they shouldn’t. Instead, they should try to make themselves marketable in a way they can control, in a way that has a largely untapped potential to erase red ink-through building positive images as academic institutions. With the changes suggested so far, and the ones that follow, the SWC could make the claim that it is the conference most serious about cleaning its house. That could bring in more money in numerous ways. Corporations are more likely to sponsor games or teams or tournaments if there is little risk of jock scandals tainting their unassailable purity. (Despite nostalgic claims by sportswriters, there is nothing evil or new about corporate sponsorship. The very first collegiate event ever, an Ivy League rowing contest between Harvard and Yale in 1852, was completely funded by Boston, Concord, and Montreal railroads-with prizes for the winners. )

Publicly de-emphasizing sports could also bring in more money from an unlikely source: alumni. It has also been shown that more money is given to schools from alumni when athletics are not perceived to be a school’s focal point. Contrary to headlines, football-crazed boosters are not the only alums in town. Most graduates did not play football, and as they get older and progress in their chosen fields, they want to see their contributions spent in ways that enhance the value of their degrees. Donations to Tulane, which was recently denied admission to the SWC, rose $5 million after the school dropped its basketball program in 1986. This change in focus would mean more money for the entire school, which in turn would mean help for the athletic department if the university takes responsibility for fully financing athletics.

A strong focus on academics also can be used as a recruiting enticement with an athlete’s parents-parents understand better than 18-year-olds that fewer than 2 percent of college footballers make the pros. Plus, it’s a way to get out of the athletics arms race, as Sperber calls it, a situation that causes schools to go millions more into debt to build new stadiums or other facilities. And who knows? Perhaps TV execs would see the promotional value of being associated with an “academic” conference that played good football. If so, there’d be a bit for the cookie jar that the SWC lords didn’t count on.

Institutional Integrity

The Problem: Shady tactics are often the result of a university’s lax supervision of its athletic department. Administrators on some campuses are adept at ignoring a department’s unethical behavior, then letting athletic directors and coaches take the heat when caught.

Flashback: At the SWC’s first meeting in 1915, the secretary was told to write to SMU about the control of its athletic department, “certain questions having arisen about it. ”

Coaches’ Party Line: “Our president has always let the athletic director run his own show. ” —an SWC football coach.

The Solution: Have a large auditing firm conduct an ethical and financial audit every year, and turn that report over to a blue-ribbon commission of college presidents, corporate leaders, and NCAA officials. If improprieties are found at a school, the panel would vote to suspend the university from SWC competition in that sport for one to five years.

For a student athlete, taking part in sports is a privilege that should be earned. The same goes for a university-and the privilege is earned by acting ethically as it recruits, educates, and showcases its athletes.

Students are punished if they break NCAA or conference rules. The NCAA has even prohibited a University of Texas swimmer from selling homemade T-shirts to earn spending money. If the governing bodies of sports are that rigid on the athletes who provide their source of (enormous) income, they should be equally tough on the institutions that reap the financial harvests.

These SWC audits would be thoroughly performed by an outside auditing firm that looks at every detail from donations to time spent on the practice field. The report, before being made public (to further hold everyone accountable), would be discussed by collegiate and local leaders appointed by the SWC office. That group would recommend any necessary sentence to the SWC office, which would then issue punishment. The panel could include people with the necessary athletic background to understand problems, such as Roger Staubach or Drew Pearson, but would also need professors and tutors who could cogently express the interests of academia. If the audit exposed any rule breaking that could be said to impede a student’s academic development, then schools should pay the price. If a coach or administrator knew of the problem, suspension for a year-and loss of all that revenue-is adequate punishment.

If implemented, these changes would create a structure that was less ripe for corruption and more conducive to real education. But these reforms would create another problem, one of…

Competitiveness

The Problem: Already, the SWC isn’t as competitive as it used to be. D’s high-minded, idealistic reforms would make it tougher to nab the blue-chip, high-school players and would dilute the already mediocre talent pool.

Flashback: In the 1917 and 1919 seasons, Texas A&M outscored its 18 opponents a combined 545-0.

Coaches’ Party Line: “There would be no way you could have competitive teams, because of the different standards. ” —R. C. Slocum, Texas A&M football coach.

The Solution: Institute D’s 2+4 Eligibility Model.

The 2 + 4 plan would not only help indoctrinate athletic department personnel into the scary world of addition, but would also help make students more competitive. Under the plan, students could not participate in football or basketball games or practices the first two years, and they must pass 48 hours of classwork during that time (as all scholarship students must). They still could lift weights with their teams and attend team meetings. Then they would have a solid base of credit hours on which to build a degree and still have four years of eligibility left. A junior- and senior-laden team would also be older and stronger than opponents playing mostly 19- and 20-year-olds, negating some of the potential talent differences. Anyway, coaches gripe that graduation rates are figured at five years when most of their players take six years to get a degree, so this should go over great with them.

It wouldn’t, of course. The chief complaint from coaches would be that it is impossible to recruit players by telling them they couldn’t play for their first two years of school. But athletes who see universities as semipro franchises are the kind the SWC doesn’t need. And with the 2+4, the pitch to students could be that if they want to head for the pros after two years of playing ball, as more and more athletes already do now, then they could still do that and have (or be close to having) their degree.

Radical changes? To some. Perhaps. But the status quo is unacceptable, and so, too, we think, is the most draconian solution-ending the “student-athlete” fiction by setting up minor-league teams on campuses and paying athletes.

In the end, though, an even more radical change is needed. We must change the ways in which athletes, coaches, presidents, boosters, sportswriters, and especially fans view collegiate sports. It’s entertainment and business, yes. But its participants are paid to play through a bartering arrangement-a student’s athletic prowess traded for a commitment from the institution to educate that student. It’s time we make sure that our entertainers are paid in full before we ask for any more encores.

SMU: A Test Case for Reform

Cynthia Patterson knows her school is in a fishbowl. “SMU is a touchstone for reform, ” says Patterson, a former associate athletic director and now special assistant to President A. Kenneth Pye. “If SMU succeeds, it will be hard for people to argue that only schools such as Notre Dame can have academic standards and be competitive. “

It was not long ago that only Rice enforced its academic standards when considering athletes for admission, but more schools in the SWC are admitting only those students who they believe can graduate-regardless of their time in the 40-yard dash. SMU has come the farthest. Under its current admission standards for athletes, approximately 70 percent of SMU football and basketball players in the early Eighties would not even be eligible for consideration now.

That’s because in 1987, when President Pye came from Duke after the Mustangs had received the death penalty, he ordered three things from SMU’s athletic department: institutional integrity, financial solvency, and the integrity of the athletes. If more scandals arose, Pye vowed, he would recommend to SMU trustees that athletics be abolished.

Despite the strict mandate, basketball coach John Shumate and athletic director Forrest Gregg, both of whom played pro ball with athletes who couldn’t read a menu, embrace SMU’s tougher standards. They say having athletes who belong at a university makes their job all the more rewarding. Now they have the daunting task of proving wrong the skeptics who say athletic success and academic integrity are incompatible.

Even with a clearly defined goal, however, SMU works to keep its priorities straight. “We will have success,” Shumate announces. “But not at the expense of the kids. ”