Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

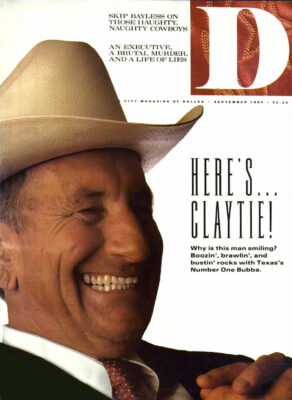

Claytie: The Video: The film is not as explicit as many you can rent today, but it provides graphic proof of one thing: Clayton Williams knows how to have a good time.

This funny home video was shot about five years ago at a black-tie cattle auction in Midland. (This does not mean that the cattle were wearing black ties, so it’s not to be confused with the time Claytie auctioned off the heifers wearing $3,000 strings of pearls. That’s another story.)

Lavish displays of material wealth have never been labeled a sin in West Texas, and this occasion is no different. The ladies of upper-crust Midland are flaunting their rocks and furs the way Mussolini flaunted his tanks. As for Claytie himself, he’s definitely three sheets to the wind. Let’s listen.

Claytie clutches the microphone, his voice drowning out the auctioneer. He’s cutting a private deal with a bidder. If this guy will offer $43,500 for a black cow, Clayton Williams will sing “The Eyes of Texas.” As any native Texan realizes, a true-maroon Aggie would rather be caught reading Wordsworth than singing the official song of that Other School down in Austin.

But what’s this? The good ol’ boy puts down his money and Clayton Williams, literally glittering in a purple sequined dinner jacket, takes the microphone and bursts into song. “The eyes of Texas … uh … the eyes of Texas are upon you … uh … I’ve been workin’ on the railroad … somebody help me with the words … till Gabe-rul blows his h-o-r-n-n!”

Later in the evening, after the booze has kicked the celebrants into another dimension, and grown men are stumbling over match-sticks like they were logs, the crowd of wealthy Midlanders hears more of the music of Clayton Williams. Now he’s singing with a country and western band called Shade Country. Strumming on an electric guitar, Williams bellows out a 20-minute aria, the words of which are as murky as they are at those operas that the big boys of Midland attend, at gunpoint, with their culture-starved wives.

Certain terms, like “Aggie, rodeo, and big buckaroo,” can be understood, but that’s about it. Finally, Clayton Williams finishes his song. An admirer throws his arm around the virtuoso and says, “Damn, Claytie, that was great.”

Williams, drink in hand, turns to the Shade Country band and shouts, “Boys, get it goin’-quick. These people are so goddamn drunk they think I’m great.”

Claytie: The Coronation: Five years later, those who fear and loathe Clayton Williams must wonder if the voters are as drunk as the Midland fat cats on the night of that auction.

At the biennial tribal ritual known as the Texas State Republican Convention, an emotional, grandiose exhibition of red, white, and blue held in late June at the Tarrant County Convention Center, Republicans believe a changing of the guard is at hand. After a century of Democratic domination, the convention would be the ceremonial kickoff of the campaign that could once and for all time mark Texas as a Republican state. And the person to officially apply the brand to the Lone Star backside would be Cowboy Clayton Williams.

By the time he arrives backstage, Texas Republican heavyweights are poised to welcome their candidate. George W. Bush, son of the nation’s chief Republican, stands there in headphones, listening to the Rangers game and grimacing at developments at Fenway Park. “I really don’t know him,” Bush remarks, “but I met him several times at charity fundraisers when I was in the oil business in Midland. The question on my mind is how has he dealt personally with the adverse stuff that happened during the three weeks after the primary. Has all that changed him?” Bush asks. “Has this changed his zest for politics? That’s what I’m interested to find out.”

Is he the future or the past? A friend once told Clayton Williams that he couldn’t ride a horse into the 21st century. “You can if it’s the right horse!” Williams said.

When Claytie marches into the arena from a side entrance, striding through the cheering delegates and waving his white hat, all doubts are erased. What has been an angry convention, splintered by debate over abortion, becomes a coronation-in-waiting. If Claytie lost any of his zest for politics over the rape-and-weather gaffe, his spirit seems renewed now, as he officially declares war on Texas Democrats.

A graph appears on a video screen mounted behind the podium, illustrating the ominous growth of the state budget. The little bar on the left shows that Texas, as a government entity, was getting by on $4 billion in 1968. That number expanded to more than $47 billion by 1990. “Even with my Aggie math. I can see over a thousand percent increase in state spending, and I don’t know about you, but I haven’t seen a thousand percent increase in state services!” thunders the man in the big hat.

The numbers on that graph, Williams insists, represent a modest advance on a kid’s allowance compared to what will happen if Ann Richards and “the Austin crowd” are given control of the credit cards. The same thing applies to the Democrats’ approach to Texas’s public education woes, an approach Claytie likens to “putting a Band-Aid on top of a Band-Aid on top of a Band-Aid.”

Most of the speech is delivered in staccato 12- and 15-word sentences, the kind of plain talk that supporters would expect from the favorite son of Pecos County.

Specifics are few. Williams’ idea of school reform, basically, is to stress “the Three Ds … don’t do drugs,” a departure from what he sees as the approach of an Ann Richards, who, after all, is simply a card-carrying professional politician.

Flag burning comes up. Williams asserts that it took Ann Richards three days to determine her stance on the issue. “It took me about three seconds.”

Then, delegates are treated to an oral outline of what they might expect from life in Clayton Williams’ Brave New Texas. It will be, of course, a drug-free Texas, a Texas where deserving kids can anticipate a two-year shot at college at state expense. (“They’ll have to work nights, but hard work never hurt anybody.”) Finally, Texas, our Texas, will be a place where “somebody’s 13-year-old daughter cannot obtain an abortion without her parents’ knowledge.”

This is Williams’ only reference to the abortion question, and it comes late in the speech. But it serves to bring the Right-to-Lifers roaring from their seats (this one brief utterance from the nominee being the single motivation for their being seated in that auditorium in the first place).

While none of Claytie’s material rings exactly with the echoes of Lincoln-Douglas debates, it is profound enough to draw cheers and happy ovations from the throng at the Tarrant County Convention Center. And if it’s not precisely the stuff of 1990s Republicanism, so be it. Claytie has an answer to critics of his self-styled O.K. Corral political image. A friend, Williams says, “once told me, ’Claytie, you can’t ride a horse into the 21st century.’ And I said, ’You can if you’ve got a good horse.’”

A speech that was originally scheduled to last 12 minutes finally finishes 35 minutes later, closing with Williams tearfully embracing his wife Modesta, while the crowd —several thousand of whom are wearing red heart-shaped “A Lady For Claytie” buttons — roars.

Were it not for the phenomenon of Clayton Williams, the political currents in Texas might be flowing anywhere but toward the Republicans. For one thing, Williams is asking voters to send him to Austin at a time when the Republican incumbent, Bill Clements, owns the lowest approval rating of any governor in Texas history, including Mark White in the days when he was perceived as sinning against the religion of high school football. Ann Richards, on the other hand, seems to have successfully mobilized women as an organized and determined voting bloc for the first time in southern political history. Claytie’s gaffes about rape and getting “serviced” have lost him the support of even some die-hard female Republican activists. And despite what Republicans are saying about crime and drugs being the keys to voters’ hearts this year, the abortion issue is the ballot-box bombshell. Polls are showing that a majority of the electorate is sympathetic to Richards’ pro-choice stance.

So if the Democrats ever had a golden opportunity to retrieve the Governor’s Mansion from a Republican grip, 1990 would seem to be the time.

But in late summer, public and private polls continued to show Clayton Williams leading by 8 to 10 points. Campaign finance filings in mid-July showed Williams raising money at a rate of $3 to Richards’s $1. Those who say that Democrats can lie back and enjoy Ann Richards’ journey to the Governor’s Mansion may not indeed have met Clayton Williams.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author