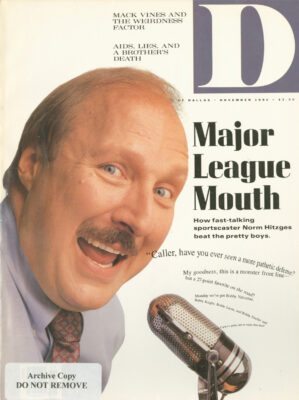

HE WAS ONCE THE UGLY DUCKling. He was Norm, the man who knew too much. He was a conduit of obscure sports information, though neither pretty of face nor husky of voice. As the sports face of Channel 4 in the mid-Seventies, he was a big-nosed Yankee and a Polish ex-schoolteacher in a Dallas market of drop-dead-handsome TV sports anchors.

Alongside the likes of blown-dry tenors Bill Macatee and Boyd Matson, Norm came off as untidy and lumbering. To radio audiences spoiled by the melodic voice of Frank Glieber, Hitzges, doing double duty on KERA 90.1 FM, sounded more shrill and goofy than earnest and informed.

Clearly, Norm Hitzges was out of place-and he was soon out of a job. In February of 1975, he was fired by Channel 4. Unable to land enough work, he left town.

Now. fifteen years later. Norm Hitzges is a media darling, a sports junkie juggernaught whose face adorns trading cups at the 7-Eleven store. He is the lone “non ex-jock” continually manning the color side of a major sports broadcast booth. He is the main ingredient in KLIF’s highly rated morning talk show recipe and a national celebrity who gets knowing winks instead of credential checks at Yankee Stadium. He is ESPN’s only analyst working twice a week and is thus flip-flopped across the country as a cornerstone of the cable network’s $400 million contract with major league baseball.

From local ugly duckling to beautiful swan in the eyes of network execs and millions of viewers. How?

“He eventually wears the competition down,” says Randy Galloway. Dallas Morning News sports columnist and WBAP talk show host. “People talk about my heavy work load. Well, let me tell you, I’m like Uncle Remus compared to Norm.”

Most recently, Hitzges was quizzed by an admirer. “Norm, I think I fell asleep watching you on TV last night about midnight. And I know I woke up with you on the radio clock at six-thirty. How do you do that?” The answer: he doesn’t know any better. He doesn’t know how not to love his work, and he can’t help but splutter and squeak that love to audiences across the city and across the country. At age forty-six, while midlife contemporaries switch careers because their working life has been devoted to something they hate, Hitzges still hits new gears of working energy. Every day his enthusiasm for sports coverage grows more genuine to his fans and more exasperating to his rivals.

It’s as if every past rejection has made Norm stronger. He’s been told “no” more often than a sophomore boy at the senior prom. He must persist. He must toil harder. Let the other sportscasters shop for their tapered blue blazers. Norm will stay at the hotel cutting out box scores and sucking on throat lozenges. He will outstudy the competition. He will outwork them.

Many things drive Norm Hitzges, One of them is a voice in the back of his mind, a constant recorded message that plays like an irritating Seventies rock ditty. It is the voice of a high-priced media consultant from Iowa, Frank Magid, who, after reviewing Channel 4 tapes, offered the studied opinion that “Hitzges will never be a major market talent.” It is the voice that swings the sword of failure and derision. A voice that says you must leave and no longer caress your first love-sports.

“That’s M-a-gd,” says Norm, spelling the name that belongs to the voice. “I like to mention his name. I mean, stations pay this guy big money and he hands down these decisions from 1,500 miles away, and your life takes this turn for the worse.”

The “worse” turn took Norm out of Dallas sports, but not even the voice of Magid-M -a-gd-could drive him back to hard news. He had nearly dozed off while covering City Council sessions for KDFW-Channel 4 and gotten queazy when covering a fire that produced one fatality. Instead he would prove them all wrong. He would blend the fireball energy of Mom Lillian with the plodding perseverance and exactness of Dad Edgar. He would make his own breaks, by God. He would show them.

“I was freelancing for everybody.” Norm remembers. “You name it. CBS, TVN out of Chicago, and the television arms of UPI and Newsweek. I was getting a lot more work outside the [Dallas] market than in the market, frankly. One year I freelanced 125 pieces.”

That was in addition, of course, to the now-legendary KERA radio sports call-in show that Hitzges kicked off in August of 1975 (and continued, in a streak Lou Gehrig might have envied, until March 1990). For the first time, with the meetings of the weekly “I-am-not-a-jock-club,” Norm had a pocket of listeners, however small and esoteric. The appeal was to sports aficionado and neophyte alike. Housewives would call and ask for an explanation of the offsides rule in football. The next caller might solicit Norm’s prognostication on the Big Sky preseason basketball tournament. Always there was a thoughtful answer, and people noticed.

In a period of his life haunted by rejection, the KERA radio show allowed Norm Hitzges to breathe deeply and exhale both confidence and sporting facts in his rushing, tumbling, staccato fashion. “I desperately needed the job at KERA,” Norm says today. “And not just for the bucks. It’s kinda like the time 1 was at the track with my friend Richie Schwartz. He bought show tickets on every horse in the next race. I told him. ’Richie, you can’t possibly make any money doing that,” and he said, ’Right now, I just need the feel of the win.’ See, KERA gave me that feeling,”

Norm Hitzges is supposed to be off today. Instead, the still blackness of a pre-dawn spring day finds him ransacking his KLIF office like some kind of drunken cheap detective, rifling through horse racing files. It is 6:16 a.

At 7:30, Norm’s two busloads of loyal KLIF listeners queue up near Reverchon Park to follow the pied piper of sports radio to “the palace on the prairie,” the Remington Park racetrack near Oklahoma City. In the first upset of the day, Norm’s wife, “Miss Vicki,” decides that on a freshly beautiful morning like this one, she’ll “go home to clean the garage.”

In the front of the non-smoking bus, many of us sit still stunned, gripping our coffees and mumbling, “did she say garage?” Mean-while, Norm can only manage a nice wave and an audible “Good Lord, now that’s a wife.” The show must go on and does, as Norm, with a large finger of sweat now gleaming down one cheek, pops in another throat lozenge and explains how to read a racing form. Next, he meticulously handicaps every race.

“Now in the fifth race, look at this horse. 1 know he was rested. Then he bled again from the nose in training. So in the next race they used the drug Lasix to control the bleeding.. .”

A fumbling, bemused busrider looks at the racing form, then at Hitzges before interrupting. “Where does it say he bled. Norm?”

“That’s just something I know about the horse.” Norm replies, in a strict schoolteacher’s tone.

No one doubts the master. Halfway to Oklahoma City, Norm orders the driver to pull off the highway to allow him to switch buses and audiences. Unlike Beetlejuice, Norm can still work two shows a day. On the ride down, of course, we are all winners. As the day wears on, however, no one doubts Norm even when his predictions prove mostly mortal.

Sixty people-bankers, lawyers, grandmas-follow the Wiejske Wyroby Polish pickle poster boy toward the paddock, He hurriedly limps up the aisle like the lone survivor of a 1970 car wreck that he is. When the good Lord performed his miracle with loaves and fishes, He received no more rapt attention than does Norm, feeding these multitudes morsels of betting information not found in the racing form. Before the horses come out on the track, Hilzges has critiqued each one with words like, “taped.” “wet” (heavily lathered), “trash” (no pedigree), and “great rear end.”

Track announcer Chris Lincoln has already let it be known that Norm will do an in-house interview today. It is eventually played on the big screen twice, but Hitzges is oblivious, riveted on his bettors’ seminar. Once, while his face is on the screen, Hitzges points to a horse circled on a fan’s program and says, “don’t waste your money.”

Bettors from both buses appear about even at the gambling windows before the sixth race, when Norm begins to pontificate about Jesse D and his two training races. Those two races are, of course, not chronicled in the Daily Racing Form, and Hitzges again grows schoolteacher)1 in tone when noting this. Jesse D goes wire to wire for the easy win. but Norm loses interest in the backstretch. To him, wins mean something more than dollars: vindication. “My knowledge against yours,” you can almost hear him crow.

Norm is the only person on either bus who brought his own pillow, and for good reason. He’ll log a quick three hours of sleep on the ride home, then be up at lour a.m. for his six a.m. Monday morning show on KLIF. Then he must hotfoot it to the crowded booth at Yankee Stadium where, for the first time, ESPN will add a second analyst to its broadcast.

In the Norm Hitzges psyche, that “winning feeling” grows out of a basic self-confidence , that has long bedazzled friends inside and out of the industry. Hitzges doesn’t look like a ladies” man (“I’m not saying he’s not cute.” says Galloway, “but I hope he doesn’t ever show up on my doorstep.”). But few have ever dated more beautiful women than did Norm Hitzges during his early Dallas years. Norm dated with the same sense of enthusiasm, persistence, and adventure that Pete Incaviglia gives to a fly ball. The doorstep that Norm occasionally shows up on these days is shared with the woman everybody calls “Miss Vicki.” Two of the constants in Norm Hitzges’s post-Channel 4 life have been the KERA show and Miss Vicki. whom he dated for seven years before they married.

He needed both very much. Because if ever Norm Hitzges felt a tinge of self-doubt, it was in 1976-77. As he says, lapsing into that automatic present-tense patter of the sportsmouth: “I’m applying for jobs around here and getting turned down. I’m applying at WFAA radio and getting turned down. I’m calling the Rangers and getting turned down.” When Newsweek suddenly called and asked Norm to come to New York, he thought, “Well, I’m not doing much good here.”

But he did well in New York. He produced and reported three national TV features a week that were piped to Newsweek’s seventy-five client stations around the country. And. of course, there was the Saturday morning talk show on KERA, his rock. And again he was noticed.

After two years he packed up his bags and (of course) his talk show for Los Angeles, where, despite the massive handicap of Ted Dawson as sports anchor. Norm became the first sports producer at KABC, the largest independent network station in the country.

With a comfortable bungalow on Malibu, many would have been content to stay. After all, in 1980 little seemed to have changed in the Dallas TV/radio market landscape. On the boob tube locally, Verne Lundquist had no peer. Other TV stations usually countered weakly only with pretty boys who could read. On radio. Brad Sham was king, and KRLD’s Sports Central ruled ratings, guests, and advertising dollars.

Sham, for one, did not underestimate Norm while he was in exile. They had worked together, and Sham knew well Hitzges’s persistence and energy. The KRLD sports director still wonders aloud: “What would have happened if circumstances had been different and he would have stayed at KABC? It’s possible that with Norm’s imagination and his grasp of the subject matter and ability to use graphics, he might well be the preeminent sports producer in television today.”

But, by mid-1980 Norm was hearing two voices. In addition to the rock-ditty voice spelled M-a-gd, there was now the best friend voice of Dallas radio veteran Kevin McCarthy, who didn’t find a happy Hitzges during a visit to the Malibu bungalow.

“I was part of the reason that Norm came back to Dallas,” McCarthy recalls. “He had it pretty good there, but he wasn’t on the air. And if you’re a performer like Norm is, there is a part of you that can go dead if you’re not getting an opportunity to perform. That part of Norm seemed lonely and withering, if not dead.”

What Hitzges liked least about producing was that “at some juncture you have to take your hands off the wheel.” Besides, Miss Vicki had visited California only once, and well.. .

Norm admits that “the goal had always been to get back to Dallas/Fort Worth.” Now, McCarthy openly lobbied for pal Hitzges at WFAA Talk Radio 57. In 1980. the station whose talk show host had once been that despicable body bag of bullying and misinformation-Superfan-began featuring the most knowledgeable sports host in America. And again people noticed.

Hitzges spent an eventful three years chatting it up with sports fans at WFAA and then WBAP. all the while courting true loves like Miss Vicki and KERA’s Sports Spectacular. Then in 1982, Vicki, the anchorwoman for the NBC affiliate in Corpus Christi, was in the bathroom brushing her hair when she decided “I wanted to be Mrs. Hitzges.” Naturally, she called the popular columnist, John Anders of The Dallas Morning News, who naturally headlined his Friday column with Vicki’s marriage proposal. “Fortunately, Norm read more than (he sports page that morning,” says Vicki.

The first morning in New York had gone well for Norm, the perfectionist. Some type of network snafu will force him to broadcast his three-hour show from his Grand Hyatt Hotel room the next three days. “The audio quality will be much poorer than we’d like,” Norm says. Life on the road has already been reduced, somewhat, to a routine. Hitzges will return phone calls and check in with ESPN in the two hours preceding the six a.m. show. Then he will nap. Like many professionals who depend upon a virtue like indefatigability. Norm has mastered the “deep sleep” nap.

The second wake-up call of the day remarries Hitzges with the phone for about an hour. Around five p.m. there is talk of eating. Norm and New Roomie cannot agree on their Manhattan dining plans. The Hitzges suggestion that we “order a big pizza pie from somewhere around here” is met, at first, with incredulous silence. The 42nd and Park hotel is surrounded by the finest restaurants in the world, but Norm wants to dine “al Trasho” in the room, where one corner looks like an old civil defense freeze-frame warning about fire hazards.

After much prompting (including the waving of negotiable currency and the assurance that “the magazine wants to pay”). Norm changes into adressier golf shirt en route to a superb Italian dinner that, his guest promises, is just a quick three-dollar cab ride away from the hotel. Perhaps work will be forgotten for an hour? Uh-oh. As the two of us scramble out the hotel’s last revolving door, Hitzges rears up like a young colt approaching the starting gate at Louisiana Downs. “My Lord,” Norm exclaims in his this-point-spread-is-way-off voice, “look at all the people waiting for cabs.”

Five people are waiting for cabs. There are thousands of cabs.

Six wasted minutes later, Hitzges leads me back into the hotel, promising that we’ll go to the restaurant for lunch tomorrow. A few minutes later, Ray’s delivers the pizza, which is large enough to look badly in need of a poolside umbrella piercing its middle. The beer is warm. Norm pays, then slips into what I guess is his work shirt.

For more than six hours, Hitzges alter-nates between preparing for the next night’s Oakland A’s-New York Yankees broadcast, preparing for the morning talk show live from the hotel room, answering phone calls (he says “no” to a Rotary Club speech and “yes” to coauthoring some kind of baby book), conducting an interview with New Roomie, and watching one baseball and two basketball games.

He first “breaks down” both the A’s and the Yankees. The civil defense corner piles higher with trash as Norm rips, tears, and pastes information from every newspaper you can buy plus newspaper columns that have been faxed that morning. Other info, some of which is personally gleaned and dating back to 1973, is neatly written on individual 3-by-5 cards.

This trash collection is beginning to take on a life of its own as Norm adds pizza-smeared napkins to the bonfire pile. “Jesse Barfield never moves anymore,” he sputters, referring to the Yankee rightfielder. “I mean he’s like a cigar store Indian out there…” Norm goes on to name the four hitters and two pitchers who recently faced each other without Barfield’s “moving more than three steps.”

At midnight or so, Norm rewards himself with half a beer before turning out all the lights. The television, of course, stays on. The Lakers are still playing on the West Coast…

AROUND THE TIME NORM AND MISS Vicki got married, a scruffy little cable station called HSE (Home Spoils Entertain-ment) offered “a junkie’s heaven” for Norm. He signed that station on the air in Dallas in the spring of 1983 and has since broadcast more than 900 HSE events.

“My God, that was great,” says Norm, with the wistful enthusiasm usually reserved for recalling a favored moral transgression. “I had a week in 1987 where 1 did an NBA basketball game, a major league baseball game, an MISL Championship Playoff series soccer game, and a boxing card. It was just great. My God, I loved it.”

Norm carried his talented WFAA producer Greg Maiuro (an unabashed fan and former regular caller to Norm’s shows) to the breakneck schedule at HSE, where the two combined their physical energies with a newfound creative flexibility to produce a five-night-a-week television talk show.

Unfortunately for almost everyone at HSE, the little station bobbed continually atop the gossipy waves of extinction. At one juncture, HSE had no station in Dallas. Thus. Norm and Maiuro and sometimes a guest were forced to fly to a Houston studio to produce the show.

When KLIF made the decision in 1986 to convert to “all talk” radio, Norm was the first hire. He insisted that Maiuro-now acclimated to Norm’s hell-bent audio choreography and occasional, radical temper outbursts (almost always stemming from “fatigue and absolutely no sleep,” Maiuro says)-be the second. Thanks to Norm, Maiuro now had two jobs. Hitzges admits now to having “something like four.”

Quite a pace, but the Hitzges belief that energy and enthusiasm will prevail has been with him since his youth in Dunkirk, New York, when his father, a machinist and bartender, broke his leg. For three weeks, Norm says matter-of-factly, “I worked at the local newspaper during the day and held my Dad’s job for him at night until he could get around again.” Hitzges passes on this nugget of personal trivia with the same enthusiasm with which he recollects the batting average of light-hitting former Ranger Pepe Frias. For Hitzges, work was never something one thought about. It was just something one did. No time to ponder questions from yesterday. Plodding, pounding, hard work held all the answers.

With the advent of KLIF in 1986, only two questions remained to be answered: would drive-lime customers listen to an all-sports morning talk show? And who would guest on a show that started at six a.m. and lasted three hours?

Knowledgeable people laughed at the concept. However, Norm maintained a loyal following, and as Brad Sham says: “KLIF was in a position where they could do something no one else was inclined to do because why not? What they were doing wasn’t working.”

Potential guests did not volunteer in droves to chat with the effervescent Hitzges at six a.m. Maiuro vividly remembers trying to track down irascible announcer Harry Caray for an early-morning spot. Doggedly, Maiuro pursued Caray, finally locating him in Chicago at a “poker club,” Maiuro recalls. “This guy. who’s obviously Harry Caray, seems stunned. Finally, he says, ’At what lime? You’re nuts, pal.’”

Hitzges was used to people saying no. But he cajoled and persuaded. “I’d say they were persistent as hell,” says Randy Galloway. “I mean, they’d give you nine dates and times. Your ass was going to be on that show.”

The novel notion of drive-time sports call-in didn’t just catch on, it caught fire. Fans holding on their car phones waited to quiz Norm during the “open line” segments. Others enjoyed the cavalcade of local and national celebrities interviewed almost daily.

Advertisers noticed. “Norm gets people under the tent,” explains Kevin McCarthy, now part of a daily lineup that includes call-in shrink Dr. Lynn Weiss and liberal-basher David Gold. “I shudder to think what would happen to our ratings overall if we had to replace Norm. Because there is no one to replace him with.”

At this mid-Eighties pace, wife Vicki roomed mostly with Norm’s personal effects in what was already a “’low-maintenance marriage.” If HSE and KLIF could not keep Norm hustling, he also produced weekly columns for both the Morning News and the now-defunct Dallas Downtown News. Then there were the forty or fifty banquets a year he emceed. “I’ll never forget seeing Norm at the Super Bowl one year and asking him if he was there to do his show,” Galloway says. “He said yeah, but he was also there to give a motivational speech to some people from Sherwin-Williams. I mean, this man just never stops.”

On those rare relaxing days at home, Vicki “tries as hard as 1 can to keep him away from television,” sometimes to no avail, “I’ve seen him watching it [sports] on TV, listening to it on the radio, and reading about it in the newspaper all at the same time. Many limes.” Norm, the romantic, can usually patch things up with flowers and flowery poems (he has published his own book of poems). The Norm and Vicki marriage is legendary in its solidarity. To dale, their longest and most violent fight revolved around whether a head of lettuce would fit into the crisper. But “when it’s bad, it’s bad,” Vicki Hitzges says. “I remember throwing myself across the bed two Christmases in a row when they had a football game on Christmas Day.”

And this was before September 1989, when ESPN came calling.

Norm viewed his chance to audition for the national sports cable channel as simply “a chance to go out to San Francisco for three days. I mean non-jocks don’t get the kind of job (hey were offering,” Norm says. Especially when the auditioning included ex-athletes like Jim Palmer, the future Hall of Famer and jockey underwear posterboy.

Even ESPN officials thought of Norm as “kind of a sleeper.” But he won the job, then fired out of the gate with such enthusiasm and energy that national media critics dubbed him a clone of college basketball’s analyst Dick Vitale-with a voice like Howard Cosell. Now the people at ESPN. like Communications Coordinator Rob Tobias, say that “with Norm, what you see is what you get. He’s not a copy of anybody. He’s the genuine article, and we think he will prove to be one of the best ever.”

PERHAPS THE WORST THING ABOUT being Norm Hitzges is getting up before room service opens. While it is 4:30 a.m. back in Dallas. Norm has been downstairs waiting on the newspapers to be delivered. The faxes from Dallas fail to reach the front desk, forcing Hitzges to write down every score he would read (hat morning.

The Hitzges mind functions like a geiger counter as it scans, then focuses, then bleeps assembled information. “My Lord, look at this game for [Roy] Tarpley! Two out of twelve from the field, two of eight from the line with five turnovers and no assists.” Norm whistles as producer Dewayne Dancer | counts him back on the air.

“. . . At 6:17 let’s jump to our open line, and it’s Al in Fort Worth who begins it.” This morning, most of the questions are about the Dallas Mavericks’ awful showing in the playoffs against Portland the previous evening. Of course, Mr. Frisky’s latest workout is discussed, as is Mike Tyson’s career. And Norm chips in an ad-lib, no-notes thirty seconds devoted to the glories of Point West Volvo.

After finishing the radio show and before (finally) leaving the hotel fora lunch with the production staff, Hitzges looks over a( the night stand and a newspaper without box scores. His eyes are curious and steady as he peers at The Wall Street Journal with the quizzical look one might expect from an early Cro-Magnon man studying a Rubik’s Cube. He finally asks for a quote on an over-the-counter medical supply stock.

At lunch, the ESPN production crew hears how Norm will pursue tonight’s story behind the story: star outfielder Dave Win-field is again unhappy in New York. Eagerly, they jot down his suggestions on graphics. Norm says they can expect to see him at Yankee Stadium no later than 4:30 p.m.- after his nap.

The maid, probably in shock, has left the room as Norm emerges clean and almost spiffy in white shirt, dark pants, and busy red-and-black-patterned tie. He seems to belie the fashion police warning that had accompanied me to New York.

Except for the handkerchief. Large? Red? Well, bullfighters in Madrid have been awarded two ears and a tail for defending themselves with less material than what now protrudes from the ample Hitzges pocket.

Maybe it was because we were dressed for the set of “Bowling for Dollars” that no taxi-driver could find Yankee Stadium. Finally, the third driver is able to pell-mell us to the press gate.

The bad news is that ESPN has been moved to a smaller broadcast booth-in truth, more like a toll booth. The good news is that Dave Winfield comes out of the batting cage wide of grin and quick of stride to interview with old friend Norm. For a change, the print media seems to huddle close by, almost horning in. Winfield has been reticent and not very quotable; perhaps Norm will elicit something new.

Back in the booth, which seems smaller than Norm’s bonfire pile, nine people are working. Engineers, producers, stat men, sound guys, light engineers, the guys from the satellite truck. All of them crawl and tape their various ways across the three-tier, 250-square-foot booth. It looks like a jailbreak.

By game time, thirteen people occupy this tiny cubicle. All chairs are removed to provide more room. The headsets are malfunctioning, so that when leadoff hitter Rickey Henderson comes to the plate, Norm hears Frank Sinatra singing “Yes sir, that’s my baby” in one ear. The trio of Mike Lupica, Norm, and Gary Thorne manages not to miss a beat (of the game-not the song).

As the evening cools, Norm is magnificent, almost eerie in his predictions. During the seventh-inning stretch he even warns that Oakland has won its last twenty-seven times in a row when protecting a lead after seven innings. The A’s promptly go on to win.

Since there are no guarantees that taxis will come to Yankee Stadium, ESPN has provided transportation for its employees after the game. Norm agrees to eat out, but only if he can still work. We go to Runyan’s (the original one, thank you), where he gives the Irish lad at the bar an envelope containing five dollars. “That’s for Burt Sugar,” Norm says. “He’s been a great baseball and boxing guest on my show many times. He holds court here a lot, So, I leave money for a drink and a tip when I’m in New York.”

A banshee-like shriek wakes me up Thursday morning. “One thing you might want to do is see if you can find Tom Diamond,” Norm is shouting into the phone. “I promise you he’s out on the course somewhere.” It seems that heavy rains in Dallas may wash out the first round of the Byron Nelson. So, naturally Norm wants somebody to find the greenskeeper at Four Seasons Resort and Club at 4:37 a.m.

Norm points to a second cup of coffee he’s bought somewhere out in the pitch dark of a New York morning. I am careful not to make much noise in our “studio.” Norm says I should go with him to Louisville and join the morning broadcast from high above the track of Churchill Downs, where the Kentucky Derby candidates would go through final prepping. I give him a look that says he and his pace are killing me.

Someone is actually looking for Tom Diamond as Norm swivels back full into thereceiver, “It’s 6:16. Our open lines beginnext…”

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman