THE PLACE WAS A FAVORED

spot for power lunches and secret deals, a private room in the posh and exclusive Tower Club on the 48th floor of Thanksgiving Tower in downtown Dallas. The day was Friday, May 6. 1988.

William Dean Singleton, then owner of the Dallas Times Herald, and James P. Sheehan, president of The Dallas Morning News’ parent company, A.H. Belo Corp., huddled with lawyers to settle a bitter lawsuit that had pitted the two newspapers against each other for more than a year.

When the top executives at last agreed, the batteries of attorneys drifted out. But Sheehan asked Singleton to hang back for a few minutes. The top man for the Morning News had something he wanted to discuss in private with the Times Herald owner.

After hawing about for a few moments about how the rival papers should try to coexist peacefully, Sheehan blurted out what really was on his mind. The Morning News, he said, wanted to buy the Times Herald.

Singleton was surprised and shocked, but he covered his reaction by raising a legal question. Would the U.S. Department of Justice, which usually frowns on newspaper monopolies, approve such a thing? Joint operations never had been permitted in other cities when both dailies were healthy.

Sheehan answered that Morning News attorneys had researched the issue for several months and had concluded that a deal could be done. But a joint operation was not what the Morning News had in mind, he explained. The leading newspaper in Dallas simply wished to buy the competing Times Herald and shut it down.

At that point, Singleton did not reveal a well-kept secret; he already had signed an agreement to sell his Dallas newspaper to a company headed by John Buzzetta, who owns it today. Terms of that contract specifically prohibited Singleton from considering offers from any other potential buyers.

But on June 1, the two executives again met at the Tower Club, and Sheehan again raised the possibility that the Morning News might buy the Times Herald. This time. Sheehan was more insistent, and Singleton finally explained that a sale was in the works. Sheehan then urged Singleton to weasel out of his deal, promising to top any offers by prospective buyers.

With that bold move, Belo more than demonstrated its growing impatience with the newspaper war that has raged for a decade. Though the battle had improved both dailies during the early Eighties, Morning News management seemed by its proposal to say that it was tiring of competition. The time had come to silence the Herald. Like Los Angeles. Cleveland, Baltimore, Miami, St. Louis, and a raft of smaller cities where second dailies have collapsed in recent years, Dallas would become a one-newspaper town.

Ever since the Republicans straggled out of Dallas after their national convention in 1984, the two papers have stopped battling on the journalistic front. The war has moved from the newsrooms to boardrooms and courtrooms. And it became a struggle to the death, with the smaller, weaker Times Herald almost sure to be the inevitable casually. The Morning News wanted a monopoly.

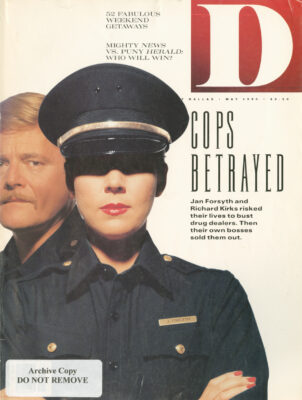

Inside the Times Herald, executives contend that Sheehan’s approach to Singleton was just one lactic in a guerrilla campaign to destroy competition. So great is Belo’s lust for a monopoly, Herald executives say, that the Morning News often stoops to dirty tricks worthy of the Nixon White House. Those tricks, the Herald insists, include smears and rumors, audit manipulation and devious deals such as the one that yanked popular comics and features off Herald pages late last year. (Morning News officials refused comment for this story.)

“These people remind me of the Watergate burglars,” says Times Herald Editor Roy Bode. “They are willing to use any tactics- anything from buying us out to smearing us in the community and planting false rumors-to destroy the Tunes Herald. There is a lot of money and a lot of power at stake, and they want it all.”

Indeed, the stakes are high. In a city where competition helps hold newspaper advertising costs per thousand readers to unusually low levels, a single surviving daily could boost rales dramatically. And without a competitor to keep it honest, the News could trim staff and reader service at the same time. Increased revenues would go straight to the bottom line.

Analysts estimate that Belo stock, recently traded at about $35 a share, would easily be worth $55 if the Morning News were a monopoly in Dallas. For Sheehan, who owns some 25,000 shares of Belo stock, such an increase would bring a handsome windfall. Chairman Robert W. Decherd, who controls something in the neighborhood of 2 million shares, would reap a sizable bonanza as well.

Just as important, the Morning News could wield power not known in a major American city since the rosebud days of William Randolph Hearst’s empire. As the only editorial voice-most local broadcasters avoid editorial positions-it could elect candidates, build monuments, and rule the public budget.

Had Sheehan broached the subjecl of a possible buyout just thirty days earlier, the News might well be the only daily in Dallas today. For months, Singleton had searched for the cash he needed to buy several smaller newspapers, an activity he loves much more than he enjoys running publications. A deal with Belo, a multimedia corporation with $720 million in assets and a cash flow of $42 million a year (according to the annual report for 1988), would have been safer and easier to put together than the sale to Buzzet-ta’s fledgling company.

And while the Justice Department undoubtedly would have scrutinized such a purchase, sources say Belo lawyers had spent months in cautious, off-the-record conversations with Justice Department attorneys, finding ways to overcome objeclions. Belo also reportedly had hired a Chicago economic consulting firm experienced in creating newspaper monopolies in Cleveland and other cities. That Sheehan was willing to approach Singleton suggests the News was confident it could go ahead.

One way or another, the News would become the only daily newspaper in Dallas, Texas.

IT WAS THE WEEK BEFORE THANKSGIVING. 1989, and word shot through the Times Herald newsroom like a scourge. The time had come. The paper was closing. More than 200 reporters and editors, along with nearly 900 other full-timers who toiled each day to produce a newspaper, would be pounding the streets. A meeting Editor Roy Bode had set for that Friday afternoon would bring the final blow.

With grim foreboding, they huddled around the city desk at the appointed time. Sportswriters, columnists, copy editors, news clerks wailed with knotted stomachs for the guillotine to descend. When Bode climbed atop a desk and grinned his off-center, Cheshire cat grin, more than one person in the room murmured, “That callous bastard.”

“We’ve all been hearing rumors for weeks that the Dallas Times Herald is about to go out of business,” Bode began. The staff nodded in bleak agreement. “I’ve called this meeting to put those rumors to rest once and for all.”

Times Herald staffers barely heard the rest of what their editor had to say. Most were so gripped with relief that they couldn’t even cheer. The eyes of some hard-bitten veterans flooded with tears. They were not out of jobs after all. Bode wheeled out cases of wine. beer, and soft drinks, and production on the Saturday and Sunday papers ground to a standstill as the staff toasted the continued long life of the Dallas Times Herald.

That so many persons who earn their livings collecting, writing, and editing the news so thoroughly misread the situation inside their own newspaper says something about the fallibility of journalists. But it also reveals a great deal about the strength and pervasiveness of the rumors that had plagued the Times Herald for a year or more. Throughout the city, advertisers, readers, journalists, and casual observers believed- and many continue to believe-that the paper’s demise was just a matter of time.

Certainly, the Times Herald has long shown many of the classic signs of a failing newspaper. Circulation, while not declining, has not kept pace with the gains at the News since 1985. Advertising has tapered off, and the once fat daily and Sunday editions have grown thin and anemic as a result. Ownership has churned rapidly enough to place the paper in the hands of three different corporations in less than four years.

But while the Dallas Times Herald undeniably is struggling, many of its vital signs are strong. It consistently turns an operating profit. It commands loyalty from readers and advertisers rarely afforded to the smaller paper in a two-newspaper market. And after several false starts, the paper recently has developed an individual style and personality that set it apart from the News and may help it attract new readers.

“It’s easy to accept the mythology [that the paper will fail] because there is a history of second papers not making it,” says Phil Meek, former publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and now head of the publishing group for Capital Cities/ABC Inc., the Star-Telegram’s parent company. “But there is no guarantee that a second newspaper can’t make it. If there is any city in this country where two newspapers can coexist, it’s Dallas. I think John Buzzetta has figured out the formula for success.”

Because Buzzetta’s company, DTH Media Inc., is privately held, it is difficult to measure the success of the formula in concrete terms. Profit and loss statements are not public information, so it sometimes is necessary to rely on the word of those closest to the company in assessing performance. But the message from inside the Herald executive suite is one of confidence and optimism.

Times Herald President L.L. “Ike” Massey. best known as the executive accused of dumping slugs in Dallas Parkway toll booths, insists, “We are paying our bills. We are paying our debt down, and we are making a profit.”

Singleton, who retained a 20 percent share when he sold control to Buzzetta for an estimated $140 million, confirms Massey’s assertion. Singleton says the paper recorded operating profits of roughly $1 million a month when the sale took place, and the picture has improved since then. “I see the financials on the paper every month, and I can tell you. it is making money.”

In fact, observers such as Wall Street investment analyst John Morton of Lynch Jones & Ryan in Washington, D.C., believe the Herald has operated in the red in only two quarters during the past two decades. Those were the first two quarters of 1986, immediately before Singleton bought the paper from Times Mirror Company, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, at a bargain-basement price that worked out to about $90 million.

Singleton staunched the losses through a painful, some might say ruthless, campaign of cost-cutting. Buzzetta intensified that campaign. The current owner shaved newsprint costs, the single biggest expense item in any newspaper’s budget. He combined inefficient delivery routes and lopped off a few that made little sense. “We saved about $40,000 a year when we stopped delivering fourteen papers a day to Graham, Texas, Dean Singleton’s hometown,” says Massey.

Paring personnel from the executive suite to the mail room produced the most significant savings, Massey says. Where Singleton employed a publisher to oversee daily operations, Buzzetta handles those chores himself and saves about $250,000 a year in the process, Amputating one whole layer of newsroom management and cutting the number of top editors in half freed up something like $500,000.

Overall, the news staff dropped from 315 in early 1986 to a current complement of 215. Many of the lost positions came from bureaus that were closed in New York and several Texas cities. But other reductions cut to the heart of the daily paper. Fewer columnists contribute their personal insights. Fewer reporters cover beats.

“We are spread a little thinner than I would like to be,” says Bode, who took over as editor when Buzzetta bought the paper. “I have to admit that we sometimes miss a story that the Morning News doesn’t miss. And we don’t have as many veteran reporters who really understand the city as I wish we could have. But I think we still are very much in the ball game when it comes to covering Dallas and Texas news.”

In addition to slicing costs, Buzzetta scouted out new sources of revenue. Taking advantage of idle press time to print publications, such as the financial newspaper, Investors’ Daily, for other companies reportedly lured several millions of dollars into the till. Likewise, the Herald may soon clinch a multimillion-dollar arrangement to print and distribute The National, the ambitious sports daily. Increasing the newsstand price of the Sunday paper from 75 cents to one dollar boosted income by about $1.4 million. Passing the price hike on to subscription customers {which Bode says is not an option) could produce another $3 million a year.

The result of reduced costs on one side and increased income on the other is a lean, vigorous, muscular newspaper, according to outsiders who know the company well. Tom Johnson, who led the Times Herald through much of the Times Mirror era, follows the paper closely and believes it is fit enough to endure indefinitely.

“They have reduced costs and improved revenues so significantly that I have no doubt they are now generating positive cash flow,” says Johnson. “Right now, the Times Herald is economically in the black. I don’t think there is any reason to worry about the future of that newspaper. It is in Dallas to stay.”

Despite such assessments from persons in positions to judge, rumors of the Times Herald’s imminent collapse persist. Among Dallas business leaders, especially, the question most often voiced is not “Can the Herald make it?” Instead, retailers, advertising executives, even politicians ask each other, “When will the Times Herald fold?”

This lack of confidence may be the greatest peril the Times Herald currently confronts. Readers who fear the paper’s failure subscribe cautiously, or not at all. Advertisers hesitate over contracts that may commit them-and their money-to purchase space the daily may not live to deliver. Suppliers demand their cash up front.

“There is no doubt that the rumors hurt us,” says Massey, “People just don’t want to do business with you when they think you are about to go out of business. We are not going out of business. We are doing fine. I wish I knew where the perception that we are in trouble is coming from.”

In fact, Massey and others within the Times Herald think they do know the source of the deadly rumors. Much of the bad news about the Times Herald, they suspect, is spread by The Dallas Morning News. Times Herald advertising representatives say clients have been warned about the paper’s imminent failure by Morning News ad reps. Herald circulation managers claim News carriers tell subscribers not to pay the Herald in advance because they may not receive many more papers.

Evidence is scanty, but Times Herald executives firmly believe the competition seeks to undermine their business through whispers and innuendo. “Maybe it is paranoia, but I am sure in my own mind that most of these rumors are coming from our enemies down the street,” says Bode.

ROY BODE IS NOT. NORMALLY. AN EXCIT-able person. In fact. Times Herald reporters call him “Stoneface,” apparently referring to his consistently bland and unreadable countenance. But on that day in August of 1989, Bode was excited.

“They’re stealing Doonesbury,” the Times Herald editor shouted into the telephone. “They’re trying to gut our newspaper.”

Bode’s outburst was prompted by the news that Universal Press Syndicate (UPS) planned to yank the popular cartoon strip, Doonesbury, and twenty-five other comics and features out of the Times Herald. By November, such staples of the lifestyle section as Erma Bombeck, Dear Abby, and Wonderword would move to the Morning News, along with a handful of comic strips and Op-Ed page columnists like James J. Kilpatrick. The syndicate would no longer do business with the Times Herald.

To explain its action. UPS revealed that it had entered into a joint venture with Belo to produce television programs based on some syndicate features. Conditions of the agreement, for which Belo reportedly paid UPS $1 million, included a provision that “blacklisted” the Herald, or so the paper charged.

Times Herald President Massey would not reveal the number of subscribers who switched to the Morning News along with UPS, but in early April, Bode told his own paper that the number was more than 10,000.

In the long run, though, losing UPS features apparently triggered a reevaluation of the lifestyle section that resulted in the brighter, more colorful package published today.

“We had already been looking for ways to improve the section,” says Bode. “But when we lost features that had been anchored in that section for years, we had to get our redesign into the paper as soon as possible.”

According to Bode, the redesign of the section, now called “Lifestyle,” was built on research showing that the Herald’s greatest strength is its appeal to women readers. Though the Morning News leads in nearly every other demographic category, almost 60 percent of Dallas women who read newspapers prefer the Herald.

“We aimed the new section almost exclusively at working women,” says Bode. “We didn’t want to go back to the kind of woman’s pages that you used to see, full of homemaking tips, child care, and gossip. We wanted a section that would be interesting and useful to women with careers and families and a lot of other interests.”

Introduced in February, the new section packs short, newsy items on health, fitness, psychology, child care, and similar women’s magazine subjects into a front page column. Feature stories, now longer than those published in the past, address such issues as taxes, job strategies, and dressing for success. For the first time, full-color photographs are reproduced on the inside pages, and there is more color on the front page.

“Some men don’t like it,” Bode concedes. “But men are not the readers we are trying to reach in this section.”

While the revamping of the lifestyle sec-tion is the most noticeable change in the Times Herald since Buzzetta bought it in 1988, other news pages have undergone gradual alteration. Human interest stories, frequently played under National Enquirer-style headlines, usually top the front page. Reports on international affairs, Congressional politics, and similar important but dry subjects occupy less space than they did two years ago and usually appear inside the first section, rather than on the front.

Economics dictated at least part of the shift in news emphasis. Because the news staff is less than two-thirds as large as it once was. Bode resolved to deploy his troops where they could do the most good-in local and state news coverage. Wire services now supply most national and international stories, and that is one of the reasons those stories now are less prominent.

“We want to be a good regional newspaper,” says Bode. “We don’t try to cover the whole world with our own reporters and bureaus any more. Our primary goal is to give readers the information they need about the city and the state. We just don’t have the staff to do everything.”

As a practical matter, retaining a larger staff would mean only that more stories go begging. Advertising declines force the Herald to print thinner papers, which automatically means fewer pages for news. And on the pages that are produced, news accounts for only about 35 percent of the package, compared with about 50 percent four years ago,

According to Bode, economics also led to the recent shuffling of editorials and columns from the first section to the Metro pages.

“I don’t really understand the technical reasons, but something about our presses makes it difficult to print a section smaller than six pages.” says Bode. “We don’t usually have enough metro news to Fill six page’s, and metro sections don’t attract advertisers at any paper I know of. We moved the editorial pages to get more bulk in the section so we could print more efficiently.”

Whatever the reasons, Times Herald editors feel their paper finally has taken on a personality that makes it a distinct and memorable news product, “We tried several different things before we found our own voice,” says Bode. “I think we have found it now. The response we have gotten tells me that most of our readers like it, and I am very pleased with it.”

Despite Bode’s rosy view, however, the loss of UPS features still stings Times Herald management. A suit the paper filed to recapture its lost features, or at least to recover damages, went to trial in Houston in early April. In its suit, the Herald contends that Belo’s agreement with UPS was a “predatory act,” that it had no other purpose than to damage, and perhaps destroy, the competition.

Though the agreement between Belo and UPS was based on Belo’s alleged plans to develop UPS features for television, the Herald contended that Belo has no facilities to produce such programs and UPS owns few of the necessary production rights. Of course, that was before the March announcement that “Universal Belo Productions” would co-produce, with a California animation studio, television programming based on the UPS comic strip Tank McNamara.

The Herald presented similar arguments in a recent petition to the Federal Communications Commission challenging Belo’s license to operate WFAA-TV, Channel 8. According to the Herald’s complaint. Belo has unfairly used its Dallas television clout to restrict free competition among newspapers.

Arguing in lawsuits that Belo is determined to destroy the second daily is nothing new for the Times Herald. During most of the two years in which Singleton owned the paper, another suit setting out the same contention in even stronger terms was argued in federal court.

In that suit, the Times Herald claimed flatly that the News sought a monopoly. “Dallas…is one of a handful of cities still fortunate enough to have two profitable newspapers in commercial as well as editorial competition with each other,” said the Herald’s petition filed in federal court in Chicago. “The Morning News is attempting to eliminate Dallas from this short list.”

Settled just before Singleton sold his newspaper to Buzzetta, that suit claimed the Morning News artificially inflated circulation figures by a variety of bookkeeping tricks and fraudulent circulation practices. Not only did the News report inflated sales figures to the audit agency, the Audit Bureau of Circulation, it even paid circulation managers to deliver papers on streets that did not exist, the Herald contended.

During litigation, the Morning News filed a countersuit accusing its competitor of many of the same practices the Herald alleged. And because the suit was settled out of court, no judge ever ruled on the merits of the arguments. Only depositions taken while the suit was pending provide real clues as to what the outcome might have been. Many of those depositions, taken from Morning News circulation supervisors, suggest that the Gray Lady of Young Street was. in fact, involved in a dirty tricks campaign against the competition.

Anyone who lived in Dallas in the early Eighties recalls a different kind of newspaper war. Publishing, in those days, was much as Richard Sheridan described the conflict in Ireland. “Happy wars and sad love songs.” Both papers improved because each sought to outdo the other in the quality, scope, and usefulness of its product. Now. though, the major front is in the courts.

“We didn”t want to take the battle to the courts,” says Massey. “We had hoped, when Buzzetta bought the paper, that all of that bitterness was behind us. But the News forced us back into court when they took the comics. We couldn’t tolerate that.”

TOM JOHNSON ALMOST GAVE UP ON the Dallas Times Herald five years ago. He was shuttling back and forth between the paper here and his primary duties at the Los Angeles Times, and the strain was wearing him down. He was ready to consider selling the Times Herald even if it meant ending the two-newspaper tradition in Dallas.

“Tom and I had a private meeting in which he suggested that we might like to buy the Times Herald,” recalls Phil Meek, who was publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram at the time. “He wanted to know whether we would be interested in some kind of joint venture or in buying the paper. I thought about it for a couple of days and told him we were not interested.”

According to Meek, lack of interest at Capital Cities/ABC was due largely to Federal Communications Commission rules. If Cap Cities bought another newspaper in the Metroplex, the FCC could require the company to sell two lucrative radio stations, WBAP-AM and KSCS-FM. The long-term profit potential for radio in Dallas appeared to far outweigh the opportunities in newspaper publishing.

However, the Star-Telegram has reopened conversations with the Times Herald several times in the years since. Nothing ever has come of the preliminary negotiations. Nor have other prospective Times Herald suitors concluded that a deal for the city’s second paper would make a good marriage.

Analyst John Morton contends that the biggest factor logged in the Times Herald minus column is its share of local advertising revenue. Morton argues that when a second paper prints less than about 42 percent of the daily newspaper advertising in its market, it is on the road to collapse. In 1989, the Times Herald’s local advertising share was only slightly above 39 percent.

But Dallas is not a typical market, and the papers here may not fit Morton’s national model. Meek describes this city as unique because relatively few people read either paper. Oddly enough, he says, that fact works to the Herald’s advantage.

“In cities where second newspapers have failed, the dominant daily typically has reached 55, 63, or 71 percent of the households in the circulation area,” says Meek. “In Dallas, the News goes to only 31.6 percent of homes, while the Times Herald reaches 22.7 percent. That means an advertiser must buy space in both papers to even hope for a minimum saturation level of 50 percent.”

That means, he says, that advertisers still need the Dallas Times Herald, just as they have for years. Despite the Morning News’ obvious advantages, neither paper in Dallas delivers enough readers to stand alone as a medium for the savvy ad man’s message.

“The trick to long-term survival is just making the next couple of years until the economy comes back,” says Massey. “I think that’s doable. If we can do that, the Times Herald will publish as long as people want to read newspapers.”

How long will that be? Singleton, who owns some five dozen newspapers across the country, predicts the industry can look forward to at least twenty more good years. After that, electronic technology may provide new and better ways to disseminate information.

“Newspapers won’t be here forever,” he says. “But until somebody comes up with something better, I think it’s important to have newspaper competition in cities like Dallas. It’s important to have several different voices.”

Adds Bode, “The Dallas Morning News is an important voice in this community. But so is the Dallas Times Herald. If the News will back off and quit trying to put us out of business, there’s no reason we can’t both contribute to this community.”

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.