FOR WEEKS, JAN FORSYTH HAD been practicing, working tirelessly during her off-hours with Tiger Paw, a sleek, chocolate-brown Tennessee walking horse with a fiery temperament. Since she had started riding again four years earlier, much of the Dallas police officer’s free time had gone into perfecting her technique, sitting in an English saddle, moving with the horse’s unusual prancing gait. For someone who had grown up around White Rock Lake riding Western-style on quarterhorses, the new style brought a new challenge.

But it was a welcome challenge, because it took Jan far away from the strange demands and often frantic pressures of her job as one of the few female undercover officers in the Dallas Police Department-making drug buys, working as a decoy prostitute, setting up a rape sting with herself as bait. By all accounts, she was one of the best. Tall, willowy, with long curly hair, Jan was frequently on “loan” to federal agencies anxious to use her in their own undercover operations. Just days before, she had been nominated for Officer of the Year by her peers.

All the work had paid off, not only in her career, but in her hobby as well. On September 2, 1988, she returned from her trip to Sewanee, Tennessee, where she had taken several ribbons in the Walking Horse Championships.

But work was never far from her mind. For months, Jan and her partner, Richard Kirks, had been working an undercover operation with the help of confidential informants. It began as a mid-level sting of dope dealers and thieves, but recently had escalated to a much larger, more dangerous federal case when the two realized they had an opportunity to bust a “Class One” dope dealer. For several years, various agencies had attempted to make a case on this Dallas man. who was regarded as one of the kingpins in the sale of “crank,” a white powdered amphetamine that users snort or inject.

The war on drugs had only recently become a national obsession, but Richard and Jan had been on the frontlines of the battle for years, working quietly, without much acclaim from the public or the politicians. In fact, they shunned recognition, as all undercover cops must. For this case, as in most operations, they used aliases. She was posing as “Diane,” a banker’s wife who bought and sold drugs, and Richard was her brother, ’”Joe Bob.” When Jan left for the Tennessee horse show, the plans were for Richard to send in an informant, wired with a tape recorder, to set up plans with the target to bring in 1,500 pounds of cocaine from Florida.

But while Jan was out of town, the nightmare feared by every undercover cop came to pass. The target of the sting had learned that Jan’s informant was a snitch. He knew Jan Forsyth was a cop. Her life was in danger.

When Richard told Jan the grim news, she was too stunned to believe him. Maybe the target had just taken a wild guess; it wasn’t uncommon for paranoid dope dealers to accuse an associate of being a snitch. “No,” Richard said. “He knows you’re a cop. He knows your name, your husband’s name, and where he works.”

In the pit of her stomach, tear and confusion were churning wildly. There was no telling what a major dealer or his lieutenants might do to her or her snitches on the street. And her husband, a sheriffs deputy, was furious, wondering how a drug dealer got that information. Only those with law enforcement ties knew who Jan and Richard were.

The partners would find the surprising source of the leak-an attorney deeply enmeshed with their own narcotics department. But that was just part-and not the most surprising part-of the long, convoluted tale of Jan, Richard, and their undercover operation. In a sense, their tangled story is like a darker version of the Arlo Guthrie song, “Alice’s Restaurant,” in which, after a marathon of twists and turns, the end of the story seems impossibly remote from the catalyst. (“Remember Alice?”)

Ultimately, it’s a story of betrayal: the betrayal of street cops not by the bad guys, the dealers, but by their own supervisors within the Dallas Police Department, who then mounted a cover-up to get themselves off the hook. One federal agent puts it this way: ’Their lives were jeopardized by not only the crooks, but by the Dallas Police Department.”

“This thing just smells to high heavens,” says one investigator involved with the case. And the smell, he says, carries not only all the way up to the office of Mack Vines, the chief of police, but to the offices of the DA and the FBI as well. Some key players believe there is enough evidence to indict Mack Vines on federal charges of concealing a felony.

NOW THIRTY-SIX. JAN FORSYTH WAS ONE of the first female police officers to join the Dallas department. She had grown up in Dallas, attending Woodrow Wilson High School. After enrolling in five different colleges, in half-hearted pursuit of a career as a physical education teacher, Jan eventually got a degree at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Meanwhile, she was working as a secretary to several police officers, among them Billy Prince and Lowell Cannaday, who would later become leaders in the department. “I got bored with typing,” Jan says in a throaty Texas drawl thick enough to pour in coffee. “A little ol’ clerk had become an officer. Well, so could I.” In December 1976, Jan went to work as a patrol officer.

She moved up through the ranks-first as a burglary detective, then to narcotics in 1982. Born with what she calls “a gift of B.S.,” Jan had long wanted to work undercover. Now she found that she was good at penetrating the clandestine networks of Dallas’s drug trade. And she was proud of her work. “For the first time in my life, I felt I was really good at something, better than the average person.”

Genuinely friendly, quick to laugh, self-deprecating, extremely attractive-Jan’s persona is magnetic, reminiscent of a best friend you knew years before. That ability to be everyone’s friend, says Richard Kirks, has been the key to her success.

At forty-five, Richard looks like Robert Redford’s harder-living older brother, lines deeply etched around hazel eyes by sun and wind, his sandy hair permanently tousled. Born in Fort Worth, he was reared there and in North Carolina, where his bootlegging father had a still.

After serving in the Marine Corps in Vietnam, Richard returned to Fort Worth and became a police officer. He moved over to the Dallas force in 1970 in order to work while he went to college. In 1978, he became a special investigator for the DA’s office, and in 1979, he started working narcotics.

Richard and Jan had known each other casually since she was an eighteen-year-old secretary and he was an officer. “She always had a Bible with her,” Richard says. But as Jan gained experience, the Bible was no longer around much. Her language grew almost as salty as that of seasoned undercover officers.

For two years in narcotics. Jan and Richard worked as partners, often riding a Harley-Davidson that had belonged to a dope dealer named Indian John; he’d had the bad luck to die of a heart attack during his arrest.

The two officers hit it off instantly. Though they had very different personalities-where Jan was easygoing, Richard was intense-they found a rare chemistry that allowed each to know what the other was thinking while things were moving too fast to talk out loud.

She wore a headband, her hair long and blond: Richard, who has a reputation for concocting weird disguises, wore a beard and straggly long hair. They looked like a greasy biker and his old lady. Richard was one of the handful of male officers who would work bikers with Jan; others complained that it was too dangerous.

“That Harley was great,” Richard says. “It served as a great introduction. Everybody wanted to know about our bike, and Jan’s very attractive. It just kind of stuns them. The last thing they’re thinking is she’s a cop.”

They would make dope buys off the bike. Then, later that same day, Jan would put on a silk dress and venture into the chic clubs of North Dallas, making buys from the higher end of the drug food chain. They both earned reputations for making cases that stuck, and making them honestly. Richard’s record shows only two “while copies,” the official reprimands issued to officers who violate procedure. One is for being late to work. Another time, he returned a pool car to the wrong space. Jan has none. Their peers praise the partners’ integrity.

Richard was known for his meticulous record-keeping, but that didn’t mean the two always operated strictly by the book. Like most undercover cops, they were keenly aware that many of those making the rules have never worked undercover.

“Jan and I had our ways of doing things, different from how the administration might view things, but nothing rebellious,” Richard says. “On the street, there is no protocol. When in Rome undercover, you have to at least appear to be Roman.”

Their relationships with informants, the street spies who are the backbone of undercover work, were precarious. Jan says snitches have strange and varied reasons for wanting to provide information to police; almost all are involved, off and on, in some type of criminal activity. A good undercover officer walks a fine line in controlling his informants-he has to be willing to arrest them if they violate the rules, “I can’t control them twenty four hours a day,: Jan says.

Her operations were often danger-ous. Once, a week after arresting a Cuban dope dealer, Jan walked into a hotel room to make a buy. The Cuban, out on bail, was there with four other men, all with guns. Though terrified, she bluffed her way through it; the man apparently never recognized her. During another buy, arresting officers showed up too late, while Jan’s gun was still in her purse a few steps away. She poked her finger into the back of the dealer’s neck and barked: “Freeze!” He put his hands up.

Jan Forsyth and Richard Kirks were the crème de la crème, setting a high standard for their peers. The Drug Enforcement Agency, the Treasury Department, and the FBI began borrowing them to help with their own investigations. Jan even applied to the DEA for a job and was accepted, but turned it down when she realized it meant a move to New York. “I guess I’m just a homebody,” she says.

Her goal, like that of many officers who like undercover work, was the DPD’s intelligence department, where officers concentrate on gathering information and working larger sting operations. In late 1987, Jan was on loan to the intelligence division, where her former partner Richard had been transferred. They chose her to sit up in a North Dallas apartment for three weeks at night as “bait” for a serial rapist known to be in the area.

“Her instructions were incredible,” says Richard, who was teamed up with Jan again after working with her years earlier. “She could not have a gun, She was to allow him to come into the apartment, get on top of her, and stick a knife to her throat.” Then Richard and other officers hidden in the closets would leap out and make the arrest. Though the suspected rapist climbed onto her patio one night, he did not come into the apartment

“He never hit me,” Jan says, snapping her fingers in mock regret. “Hurt my feelings.” That first assignment went nowhere, but other action quickly followed. In December 1987 Charlie Bruton, an informant Jan had developed during her time in narcotics, called with a deal. The black sheep of a once-wealthy southeast Dallas family-a one-time rodeo cowboy, pro football player, and “alligator wrestler”-Bruton had been convicted for theft and wanted to work off his probation. Was she interested, Bruton asked, in making a case on a thief and drug dealer who wanted to set up a clandestine amphetamine lab on Bruton’s southeast Dallas farm?

Like most informants, Bruton was no preacher. He lived on the edge of violence and criminal activity. But his information was always accurate, and he had a peculiar kind of courage. Like Jan, he could talk to anybody about anything. You bet, she told him. seeing the chance to make not only drug cases, but arrests of thieves and fences. Ironically, it was a decision that would ruin her career.

WHEN THE CALL CAME, ALL RICHARD COULD THINK WAS “OH, shit!” Jan was visiting relatives in Chicago, and he was sitting in a car with several DEA agents a few blocks away from Charlie Bruton’s family farm on Middlefield Road. For weeks, they had worked toward this goal, waiting for a sleek Cadillac with black windows to arrive. Now, on July 30, wired with a tape recorder, Charlie Bruton was about to be introduced to Mr. Big.

Bruton had connected Richard and Jan with a habitual criminal named Darrell Wayne Smallwood. At fifty, Smallwood had twenty-two aliases and a long string of convictions that made him a target of TOP (Targeted Offender Program), a DPD effort to identify, convict, and rearrest that small percentage of criminals who commit the vast majority of crimes.

An amphetamine “cook,” Smallwood wanted to use Bruton’s farm to make drugs. While biding their time on the dope deal, Jan and Richard, posing as Diane and Joe Bob, did “reverses,” buying stolen property from Darrell Smallwood and his cronies, then selling them property they were careful to represent as hot. They taped all their transactions; their supervisors wanted everything carefully documented.

Earlier that summer, however, the case had taken a weird turn. Smallwood’s girlfriend had come to the house in a Cadillac registered to James Coltharp, the sixty-eight-year-old owner of Debonair Danceland and reputed longtime member of the “Dixie Mafia.” The Lakewood resident was thought to control much of the amphetamine market in Texas and Oklahoma.

If Smallwood was working for Coltharp, the officers instantly knew, they had a bigger and much more dangerous fish on the line. They went to the DEA, who agreed to finance the operation only if Jan and Richard stayed on it, working Bruton. If successful, the Dallas police would not only net a major drug dealer, but almost $10 million in seized assets and a lot of good PR. So the wheels started turning. Bruton was put on the DEA payroll, and Jan and Richard began maneuvering the snitch to get himself an introduction to Coltharp.

Now, they were staking out the house, waiting for that meeting to go down. And as they waited, they learned that the unpredictable Smallwood, always desperate for drug money, had decided to break into the house next door. “He’s over there now.” a panicked Bruton told Richard over the phone. “’I can see him from my house.”

Stunned by this bizarre turn of events, the DEA agents and Richard drove by the house several times, but could see nothing. Busting Smallwood by calling in uniformed officers would blow the whole operation. Smallwood would be sure to smell a set-up. Knowing that the house was unoccupied and that it was unlikely anyone would be hurt, the officers decided to preserve the federal investigation and let the burglary go ahead. “Stick like glue to him,” Richard told Bruton. “Find out where the stuff goes.”

After the burglary, James Coltharp arrived, and Bruton taped Coltharp talking about his illegal activities. Later, Bruton went with Smallwood and his girlfriend to the home of a fence, where they sold the purloined goods. Bruton called Richard, who relayed the message to detectives in the Southeast Division. They said they would try to recover the loot and return it as discreetly as possible to the owner, who they discovered was George Grogan, a member of the City Plan Commission. It wasn’t an ideal solution, but it was the only way to preserve the secrecy of the investigation.

It was a close call. Another one came earlier when Smallwood spotted a wrecker he had stolen and sold to “Joe Bob” when it reappeared on the owner’s property. Smallwood told Bruton that Joe Bob and Diane must be cops. “Nah,” Bruton told him. “The cops were on to him and he had to ditch it. I’m screwing that girl and I’ve shot dope with Joe Bob.” When Jan returned to Dallas and heard what happened, she and Richard decided Smallwood’s ’”one-man crime wave” was too risky. They had to do something to get him out of the way.

Bruton suggested to Coltharp that Smallwood was using too much of his own product. “You and I can make some money, but I’m taking a risk with Darrell Smallwood,” he told Coltharp. Coltharp agreed: “If he gets to be too much of a risk, I’ll hire a Colombian hit man to kill him.”

To get Small wood on the street the legal way, Richard and Jan sent out flyers to police describing the dealer and his many aliases. He was arrested on August 4 on an unrelated stolen vehicle charge, and slapped with a high bond designed to keep him in jail. On the day of his arrest, Smallwood, in a traitorous move even for a snitch, offered to inform not only on Coltharp, but his new acquaintances: Charlie Bruton and the two he knew as Diane and Joe Bob.

THE ABRUPT COMMAND CAME AT FIVE O’CLOCK ONE August afternoon. Bruton called a DEA agent: “Coltharp wants to see me. now.” Not taking time to put on a microphone. Bruton, followed by several DEA agents, raced over to Debonair Danceland. Jan was showing her horse in Tennessee and Richard was off-duty, so DEA was riding herd on the operation. For weeks. Bruton had been talking to Coltharp about bringing in a shipment of 1,500 pounds of cocaine through Florida, using one of the dealer’s many airplanes. After Bruton volunteered that he was a pilot. Coltharp asked him to fly “right seat.” The DEA was scrambling to upgrade Bruton’s pilot’s license to cover the sleek turbojet Coltharp wanted to use.

Bruton emerged ashen-faced from the meeting. Coltharp, seated behind his desk, had angrily confronted him: “You’re a goddamn snitch and you’re working for that Jan Forsyth, that pretty little blond-headed bitch!”

“Naaah, no way,” Bruton protested. But James Coltharp persisted. “Yeah, and she’s got a husband named Larry Forsyth who’s a deputy out at the sheriffs department. You’re f-ing that bitch for money.”

Stunned, Bruton maintained his composure: “Hell, if that’s true, get her on the phone. I’m flat broke.” In a fury, Bruton called Richard the next day. “You’ve got a leak somewhere,” he charged.

This was their first indication that things were going wrong. Richard, wanting to make sure Bruton wasn’t lying to him, decided he had to get it on tape. When she got back from Tennessee, Jan would want more proof. “Do you have enough B.S. to go back in there?” he asked Bruton.

Despite the danger, Bruton agreed. Returning to Debonair Danceland, wired this time, he lured Coltharp into repeating his accusations. Lying brilliantly, Bruton convinced Coltharp that his tears were unfounded.

The operation was salvaged, for the moment. But that didn’t solve the major problem. Richard and Jan were worried, not only for themselves, but for their informants. But perhaps the most furious was Larry Forsyth, the sheriff’s deputy Jan had married in 1982. Jan and Larry were well matched. Each understood the demands of the job; neither wanted children. The one major bone of contention was her work environment. “He hated me doing undercover work,” says Jan. “It was a constant fight.”

Larry knew only too well how dangerous even the best undercover operation could be. He knew Coltharp’s reputation. He was scared. Somewhere they had a leak, a leak that could get his wife killed.

Their worst fears were confirmed several weeks later. On September 15, an FBI agent who was working with them to arrest a fugitive bank robber near Bruton’s farm came into their offices in the intelligence division. “I hate to be the bearer of bad news,” the agent told them, “But 1 think I found where your leak is.”

He handed them a letter written to the FBI from Darrell Smallwood in his Dallas County Jail cell, offering to exchange information for a lighter sentence.

In the letter. Smallwood described an August 23 visit from an attorney claiming to represent George Grogan, whose home Smallwood had burglarized. The attorney offered to get him an attorney and said he was “after some corrupt police, mainly Jan Forsyth, the little pretty blond bitch.”

The attorney, Smallwood wrote, had told him that Charlie Bruton was a snitch and that Jan was an undercover cop. “The lawyer says she’s a cop and lets Charlie run wild and he’s gonna put a stop to it.” If Smallwood would use a tape recorder after he got out to get something on Bruton, the lawyer would pay him $1,000.

The FBI agent, aware that Jan and Richard had had their cover blown, visited Smallwood in jail and taped an interview in which the criminal restated what he said in the letter.

“Richard and I were in shock,” Jan says. “Could it have really happened? You always wonder about people in jail.” But they knew instantly who the attorney in question was. To make sure, and to salvage whatever shreds of their operation remained, they enlisted the help of a blond FBI agent, hoping that Smallwood had been too high on drugs to remember what Jan looked like the only time they had met. The agent and an investigator from the DA’s office visited Smallwood in jail. Pretending to be Jan, the agent told Smallwood that the FBI had shown them the letter; she said she was concerned because someone had been impersonating her. They showed Smallwood a photo lineup taken from the State Bar roster, and asked him to pick out the attorney who had visited him.

Smallwood pointed to a picture. It was just as Richard and Jan suspected: their leak was a self-proclaimed “cop groupie” and a member of the Greater Dallas Crime Commission, an attorney who had his own badge as a peace officer sworn to uphold the law. His name was John Barr.

JAN FORSYTH HAD MET JOHN BARR YEARS EARLIER WHILE RUN-ning search warrants for narcotics. His badge as a deputy constable gave him carte blanche to carry a gun, usually in his belt or in his boot. A man deeply committed to law enforcement, Barr would spend his days at court or taking depositions, then run around at night with the narcotics squad. At times, he seemed to have an almost schizophrenic attitude toward his work-paying for a bond as an attorney, then leaving the bond office and returning later to collect the money for another client as a deputy constable. Another time, he filed an injunction against a nightclub, then helped enforce it. Ban also was accused of serving subpoenas for records of a bank in a civil suit he was handling for a client, a violation of state law.

At thirty-four, Barr is six feet tall, slender, and good-looking in a B-movie sort of way. He is the son of the legendary Bert Barr, a crusty old lawyer who had introduced him to what one friend calls “the good ol’ buddy system” of justice in Dallas. “So-and-so gets arrested, somebody calls the sheriff and gets it taken care of.”

Barr’s peers paint him as a charismatic and capable lawyer with a jury, but a man who still prefers to “go in the back door and clear it up” if he can, says one. “He wants to kick ass very quickly, show he can get things done.”

That, says the attorney, is why Barr was eager to join the prestigious Dallas Crime Commission, an organization dedicated to working with law enforcement on legislation and financing. “He was trying to get on the national crime commission. It was important for him to get in there and mix it up and show he was tough.”

What Barr loved most was riding around in police cars. In fact, Barr wooed officers. He would buy a luncheon table at the crime commission meetings and invite a handful of officers for a free meal. He frequently handled officers’ legal business for nothing or a reduced fee, and he went into business with several other narcotics officers, buying foreclosed property, “He would take them on hunting trips and out to eat,” says an attorney.

But Barr never did anything without a reason, the attorney says. When one local lawyer was arrested for DWI and possession of cocaine. Barr pulled strings to get the dope evidence destroyed and the possession charge dropped before the case ever came to trial. Records show the DWI case dragged on for two years before the man pleaded guilty and was given probation. “John made $20,000 to $25,000,” the attorney says, all from using his connections.

In August 1988, according to police testimony, Barr asked an officer to reduce a charge of public lewdness against a prominent family’s college-age daughter. The officer refused. When police confronted him about this conflict of interest, Barr retorted: ’That’s the way things get done in Dallas.”

In other ways, Barr showed an unnerving willingness to violate the law if it would help him in a case. Once, Barr’s client lost a nasty divorce case. Barr, who had thought the case was a cinch because his father was “in tight” with the judge, was furious. He told several people in his office: “We’ll just bug his chambers and get something dirty on him,”

Those standing around knew he could do it. Barr’s cousin, a man with a passion for high electronics, works in his office, where he is popularly known as “I Spy.” And the office was stuffed with alarm systems and surveillance cameras. Barr told one police officer he had equipment to detect a tape recorder in his office.

In early 1988. around the time that Jan and Richard were beginning their operation with Bruton, Barr was about to be named legal adviser to the Dallas County Sheriff’s Department, a potentially influential position. Sometime in February, after she had started using the Bruton farm for undercover work, Jan got a phone call from Barr at home.

Barr wanted a favor. He said he had a wealthy, influential client, George Grogan. That night, Channel 8 had aired a story saying that Charlie Bruton had told the Texas Water Commission that in 1981, long before Bruton was working with the police, Grogan, who owns a paint factory, had hired him to bury 500 barrels of toxic waste. Later, Bruton and Grogan became enmeshed in a bitter neighborhood feud over mining of sand and gravel on Middlefield Road. In 1987, Grogan had sued Bruton for digging up his property adjacent to the Bruton farm to sell the dirt and gravel. Bruton retaliated by going to the water commission.

Barr knew Bruton was Jan’s informant not only because of his connections on the narcotics squad, but because his firm had represented Bruton’s wife Susan in a hearing held during a vicious 1987 divorce trial against her first husband, a wealthy attorney.

Susan had also worked as an informant for Jan, introducing her to limo drivers and the washroom ladies at private clubs who could supply cocaine. After introducing Jan to Charlie Bruton, Susan had taken a back seat, primarily relaying messages to the officers.

Now, in one of his typical “back door” moves, Barr wanted to play the fixer. He knew that calling Jan would impress Grogan, who was on the board of the sheriff’s department’s training academy. “I need to look good for the sheriff,” Barr pleaded.

Implying that there might be something in it for her and her husband, Barr asked Jan to get Bruton to change his story, to tell the water commission the barrels were his, not Grogan’s. Grogan was selling his paint factory, and the fracas not only could prevent the sale, but might result in stiff fines.

Jan says she refused to get involved. “It smelled of a bribe,” she says. “I told him to talk to Charlie himself.” She reported the call to her supervisor.

Days later, Bruton told Jan that Barr had asked him to sign an affidavit saying the barrels were not Grogan’s. When he refused, Bruton said, Barr threatened to expose his undercover status. Then, Jan got a call from Channel 8’s Mike Devlin, asking if Bruton was a confidential informant. She believed Barr had gone to Devlin. (Barr denies that he told the reporter Bruton was undercover. Devlin, now in Portland, says he doesn’t remember who gave him that information.)

Angry and worried, Jan called her supervisor. The story never ran, She was told that Captain Willard Rollins of the intelligence division killed it with a phone call.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Barr twice went to Larry Forsyth, pressuring him to get Jan to tell Bruton to cooperate. The second visit came only a day before the FBI agent showed up with the Smallwood letter. Larry says that Barr, looking wild-eyed and desperate, stopped him in the hall at the sheriff’s department and begged him to get Jan to change Bruton’s story. “Larry, you just don’t know how much money is involved in this deal,” Barr said, adding that he knew “all about the airplane and the big case with the DEA.” Barr said he had pictures of them working at the farm.

“A lot of people are going to know where you got that information,” Larry told Barr.

“You’ll never find out where my information is coming from,” Barr told Larry, suddenly looking scared. “I want this handled off-the-record. Or your wife is going to start having credibility problems.” Larry refused, saying Barr needed to take up his concerns with Jan’s supervisors.

Jan and Richard had thought Barr was just bluffing, but with the Smallwood letter, they realized that he was making good his threats. They took the letter to their supervisors, who were surprised to learn that an attorney whose firm handled criminal defense cases was going on raids with their officers. After a meeting, it was determined that Barr was a security risk. The two undercover cops were ordered to tell the specialized crime division of the DA’s office that Barr had deliberately blown their cover. A major DEA investigation had been compromised. Not only were Jan and Richard exposed, but so were their informants and undercover federal agents.

If protocol was followed in this matter, Chief Mack Vines would have been told that Barr had gone to the jail and blown their cover, and that a number of narcotics officers were involved with him. Where else had Barr gotten his information? If Rollins did his job he also told Vines of Barr’s previous behavior. That fall, Vines was traveling frequently to Washington. He wanted Dallas to be a model city in the president’s war on drugs. Imagine the embarrassment if Vines’s own department had helped a rogue attorney undermine the footsoldiers in that war.

Within a few days, John Barr found his cozy relationship with the police radically altered. He was dropped from the list of candidates for legal adviser to the sheriff. He was told he could no longer run search warrants or visit the undercover narcotics squad’s offices. He was becoming an ordinary citizen.

Barr was infuriated: the power he had worked for years to develop was slipping from his grasp. “I’m a cop groupie and you’ve taken away my golf game,” Barr told the police captain who brought the news. He began making vague innuendos about Jan’s relationship with Bruton. The supervisor told him that if he knew of wrongdoing, he needed to file an Internal Affairs complaint. Meanwhile, the decision was final.

Furious, Barr began scheming to get his privileges back. And to get revenge on Jan. Then he heard about a “magic” telephone.

IT SEEMED THAT THE JAIL MASQUERADE had worked; Coltharp again sounded ready to deal with Bruton. But on September 28, while snooping around Coltharp’s jet at Love Field, Bruton was attacked and beaten by two men in suits. Jan and Richard never determined who the men were, but they wondered: had Coltharp decided to send Bruton a message, just in case? Bruton, who had been told by a dealer friend that there were two murder contracts out on his life, was convinced that it was Coltharp.

The attack on their snitch disturbed Jan and Richard, but the two partners had more to worry about than the danger on the streets. After being banned from running warrants, Barr had made good on his promise to cause Jan “credibility problems.” He and George Grogan, who was still angry about the burglary of his house, and two other lawyers in his firm had gone to Internal Affairs and filed complaints against Jan. Early on September 23. Captain Rollins advised Jan that two administrative charges were pending against her.

At first, Jan was relieved when Rollins told her of the complaints: she was accused of misrepresenting facts to a judge in order to work with Bruton, and of socializing with her snitches. She knew she was innocent on both counts. But later that same day, she was surprised when Rollins gave them two strange commands: they were not to “talk business” with Charlie Bruton on the phone at his house, and they were not to tell anyone that he, Rollins, had given them that order.

The officers were confused. Why was their captain telling them something so ridiculous? Jan guessed aloud that there was a wiretap on the phone, but Rollins refused to tell her anything. Richard asked if the DEA or the FBI had been notified, since their undercover agents were talking with Bruton over that phone as well.

Rollins simply repeated his orders. The two officers left his office, bewildered but resigned to following orders. “We thought there was a legal wiretap on the phone by some higher authority,” Jan says. Lieutenant Kenneth Lybrand protested in a closed-door meeting that his officers’ lives were in danger-and demanded an immediate wiretap investigation. “This is no coincidence,” the lieutenant said. Rollins said he would go to the FBI. He never did.

The mysteries deepened when Jan began to get visits from Detective Bob Jennings of Internal Affairs, who asked a string of puzzling questions. Had she told Charlie Bruton that she would give him “half the dope”? Was she Charlie’s girlfriend? Had she ever been in a lesbian affair with Susan Bruton? Did she cover up the burglary of Grogan’s house? Did she cover up a capital solicitation of murder charge to protect the Brutons, who had been accused of trying to get Susan Bruton’s ex-husband killed? Had she taken Charlie Bruton to Tennessee with her?

Jan was stunned. The accusations went far beyond simple administrative charges to paint her as a liar, a lesbian, and a drug user-any of which could lead to her dismissal from the department. Nor could she understand why Rollins had lied, telling her that she faced only administrative charges. State law requires that officers be notified of any criminal allegations in writing. “What do you expect me to do? Give her a Miranda warning?” Rollins shot back when Lybrand confronted him about it.

For a week, Jan was constantly defending herself, even getting an affidavit from a friend who went on the Tennessee trip. After years of conscientious police work, she was being accused of things she couldn’t imagine, by sources she didn’t understand. Barr apparently had made allegations relating to the Brutons, using information obtained during Susan’s divorce, but she couldn’t understand where the accusations related to their undercover operation were coming from.

Until she got a call from Richard on October 4. “You’re not going to believe this.” he said. A wiretap had been found on Charlie Bruton’s phone, just as Jan had guessed. But it hadn’t been ordered by a higher authority. In fact, it was illegal.

The day before, after a week of working off scribbled notes taken during Barr’s meeting with the head of Internal Affairs, Detective Jennings called Barr to translate the hodgepodge of allegations against Jan into written form, as required by state law. On tape. Barr told Jennings that he told Small wood. “Man, I think that girl’s a cop,” only after Small wood said she wasn’t a banker. And it was Grogan, he said, who initiated the complaint against Jan. Barr painted himself as a man dedicated to helping the department, not settling a personal score. His goal, he said, was to protect the police from “these sons-of-bitches on the City Council and people that are trying to make it harder for police officers to do their jobs.”

What captured Jennings’s attention most, according to his later deposition, was Barr’s contention that Grogan had come to him with a story about a “magic phone.” Barr said Grogan told him that the phone company had crossed the telephone wires of the Brutons and their neighbors, the Dulworths. Joyce Dulworth had been listening to the conversations between the Brutons and the police officers on this phone. Convinced that dirty cops were haunting the DPD as in the movie Serpico, Joyce and Homer Dulworth had contacted Grogan, who then went to Barr.

Jennings was skeptical of Barr’s crossed-wires story, so he asked the phone company to check the Bruton line for a wiretap. If they found a problem, they were to touch nothing and call him immediately.

On October 4. a phone company serviceman went out to Middlefield Road and, in front of the Dulworths’ home, he found the problem: bits of wire and plastic connecting the Brutons’ and Dulworths’ lines. Though the repairman knew the police department had sent him to check for a wiretap, he was about to throw the device away. But Bruton, whose wife had complained several times to the phone company about a possible tap on the line-only to be told it was clear-asked the repairman if he could have the device. Bruton gave the gadget to Richard, who put it in the police property room.

To Bruton, the connection made sense because the Dulworths were old enemies of his, going back to his testimony against them in an assault case. And Bruton knew something else: the tap meant that their son, thirty-four-year-old Gary Dulworth, a TOP offender who had been convicted of robbery and other charges, could have listened in on the details of a major DEA operation. And Barr was relaying information taken from the phone to Internal Affairs.

Though the officers didn’t know it then, their supervisors wanted to use the family of a convicted criminal to spy on their own officers. That knowledge would cause Jan and Richard to turn their considerable investigative techniques, honed during years of undercover work, on their chain of command.

SURROUNDED BY MOUNDS OF BOOKS, on December 28 Jan and Richard sat in the legal library down the hall from the police chief’s office. A month before. Jennings, who had gathered affidavits from several judges, officers. FBI agents, city officials, and others involved in the case. turned in a report that said not one of the complaints against Jan could be substantiated. And, Jennings’s report said, much of the information on which Barr based his complaints had been obtained illegally.

“I was cleared and so glad,” says Jan, who had lost fifteen pounds during the ordeal. “I figured my supervisors were just stupid.”

Now the partners were continuing the investigation of Barr that they had started after the Smallwood letter surfaced. In the interim, they had learned that Barr, whose wife is a felony prosecutor for District Attorney John Vance, had gone to the DA to ask about the investigation of him.

With John Barr sitting in his office, Vance had called Charlie Mitchell, chief of public integrity, and asked about the investigation. Not knowing that Barr was in the office, Mitchell outlined the details. The investigation, at that time limited to Barr’s exposure of police officers to Smallwood, was quickly dropped. Jan and Richard were told it wasn’t illegal to blow an officer’s cover. And besides, it came down to a swearing match between Smallwood and Barr. One police source says that the DA killed the investigation. Vance told a local paper the investigation never existed.

Vance now says he assigned Ted Steinke, head of specialized crime, to look into the matter and “scrub it out.” Steinke says his investigation did not turn up sufficient evidence to merit charges against anyone.

After the IAD report clearing Jan, the partners got permission to look at Barr’s credentials as a peace officer and discovered that he had not been approved by the county commissioners court, as required by law. In the library, they were searching the law to see what charges they could file on Barr when assistant city attorney Lewis Jaggi walked in.

“What are you working on?” Jaggi asked. They explained they were investigating an attorney who was involved in a wiretap.

Jaggi, unaware that they were the officers involved in the matter, started laughing. “Oh, yeah.” he said. “I remember that deal.” He told them that Rollins and Captain Dwight Walker, head of Internal Affairs, had come to him the day the complaints were filed against Jan Forsyth. They wanted to know if they could continue monitoring the “magic” phone.

Jaggi told Jan and Richard that he explained to Rollins and Walker that this was an illegal wiretap, and told them they could not monitor the phone or accept any complaints against officers based on information coming over that phone. Federal and state wiretap laws are quite emphatic: not only is it illegal to wiretap someone’s phone, it is illegal to use or disclose the information obtained through a wiretap “for any purpose.”

Jan and Richard cut their eyes at each other. “I got the coldest feeling in the pit of my stomach,” Jan says. Trying to act nonchalant, they pried Jaggi for more information. He left them with a word of warning: “Stay away from that wiretap deal. You’ll get your supervisors in a lot of trouble. I’m glad I didn’t write anything down.”

Everything suddenly became clear. “We couldn’t believe what we were hearing.” Jan says. “This was no longer incompetent, stupid administrators. This is knowing wrongdoing. They endangered our lives.” As much as they hated the thought, Jan and Richard had to face the unthinkable: their supervisors had known that someone was monitoring the phones-and instead of stopping it. had exposed them to the “dirtballs” they were trying to catch, Jan says.

According to police testimony, Rollins and Walker didn’t order an investigation, even though they decided not to monitor the phone, because they didn’t want to appear to be retaliating against Barr or the Dulworths. Besides. Rollins said in a deposition, Jan and Richard weren’t “deep undercover.”

The partners later learned that the bizarre chain of events went all the way to Mack Vines’s office. Vines had discussed the complaints against Jan with Grogan in former City Manager Richard Knight’s office. Cap-lain Walker and another supervisor had gone to Vines to brief him on the subject and tell him of the wiretap. According to Walker’s later deposition, Vines angrily asked them, “Why are you telling me this?”

Walker was confused. “Because this guy [Barr] is very prominent in the community,” he told the chief. “He runs in the same circles: you might run into him at a crime commission meeting.” Vines acted as if he didn’t want to know.

Now. Jan and Richard were sure they had the truth, but none of it was on tape. Several days later, on January 6, 1989, they returned to the law library and met Jaggi. This time, they had a tiny hidden recorder.

Obviously nervous, Jaggi repeated much the same story, adding that he had talked to an FBI agent in charge of legal affairs about the case. “He first wanted me to be real vague because he didn’t want to have the obligation to report the offense,” Jaggi said. Later in the conversation, talking about Barr, Jaggi muttered: “You know. . .that looks to me like you’ve got witness tampering and all sorts of stuff. . .It looks like an obstruction of justice.”

At the mention of the FBI, Jan and Richard suddenly realized why little was being done about the wiretap. After an early-morning raid on the Dulworths’ house-the search, a full week after the wiretap was found, netted a tape recorder, suction cup, and eight tapes-the FBI seemed to be doing nothing. Neither Jan nor Richard had been interviewed by them about the wiretap.

On January 9, the partners taped Udo Specht, FBI agent for legal affairs. “I said Lewis [Jaggi], you know, if you know the facts don’t tell me too much ’cause we might have to open up a case,” Specht told them. “I never heard from Lewis again.” (Jaggi, who has since left the city’s employ, declined to comment.)

They couldn’t believe it. Specht seemed to be saying that the FBI didn’t want to know about wrongdoing on the part of the police. It was clear that, aside from trying to determine who physically put on the wiretap, the FBI was not interested in the case. They suspected that Bobby Gillham, head of the FBI’s Dallas office, was doing a favor for his old friend Mack Vines.

They were thwarted at every turn. Not only was the FBI going to sit on its hands, it was clear that neither the DA’s office nor the U.S. Attorney’s office was going to do anything. Jan and Richard approached Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Webster, who initially seemed interested in pursuing the matter, but the case was ultimately dropped. Webster told the officers there was a problem with the “chain of custody,” since Charlie Bruton had been given the device found on his line.

“If Charlie’s good enough to testify over millions of dollars of dope, why can’t he testify about four wires and some plastic?” asked Richard. After Webster said he was unaware of the drug case, Richard asked him to call the DEA. Meanwhile, Barr had hired Kim Wade, a former assistant U.S. attorney and son of former DA Henry Wade. Wade and Barr had gone to the DEA and FBI, threatening to sue them.

Though Grogan says he was offered immunity to testify before a federal grand jury, it was apparently never convened. U.S. Attorney Marvin Collins says he can neither confirm nor deny the existence of any investigation. But, he added, “Dallas Police Chief Mack Vines is not the subject of any criminal investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s Office.”

Jan went to a friend with the Department of Public Safety. Knowing that the tapes were explosive, she wanted him to keep them in the DPS property room, and to see if someone at DPS would investigate. “They’re not going to want to have anything to do with bringing down the chiefs of police in Dallas,” her friend said, refusing to keep the tapes.

When word got around that Jan and Richard were investigating not only Barr but their supervisors, they were ordered to stop by Chief Rollins; he said their actions would look like retaliation. They were told that the police code of conduct prohibits officers from investigating incidents in which they are personally involved, but it was clear that no one else would be assigned to look into the situation. Their supervisors wanted the whole thing to go away.

On February 6, the day after a story on the investigation appeared in The Dallas Morning News, Chief Richard Hatler, now in charge of intelligence, told the partners he was considering transferring them, but wouldn’t at that time because their supervisors said they were doing a good job. He warned them to be sure no more stories about the controversy appeared in the press.

At this point. Jan and Richard had had enough. On February 13, convinced that no one cared that they and their informants had been endangered, the two filed a federal lawsuit against the City of Dallas, Chief Vines. Assistant Chief Rollins, Captain Walker, John Barr, George Grogan, and the Dulworths. The suit charged that the defendants conspired to violate the officers’ civil rights and exposed them to danger, and asked for not less than $100,000 each in actual damages. $10,000 each in statutory damages, and $500,000 in punitive damages.

“To protect the integrity of the department, we find it necessary to file this suit,” Jan and Richard wrote in a letter to Vines. Two days later, after a story appeared in the News about the lawsuit, Jan and Richard were transferred to patrol “for the betterment of the department.”

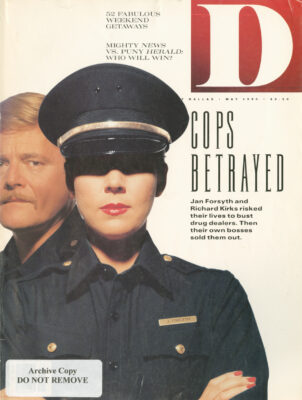

So Richard Kirks and Jan Forsyth now wear blue uniforms and blue hats. And gold name badges.

AFTER YEARS OF THE UNDERCOVER life, Jan and Richard are adapting to life on patrol. They say they have found an atmosphere far different from the one they remember as patrol officers more than a decade ago. “I was shocked,” Richard says. “You’re a glorified report taker. I’ve never seen morale as bad in any law enforcement agency as I’ve seen it right now.”

The two have become a rallying point for increasing numbers of officers dissatisfied with the department under Mack Vines. Many along the thin blue line see what happened to Jan and Richard as further evidence that street cops are expendable, that what matters is pleasing the City Council and special interest leaders. Critics among the rank and file believe their chief and captains bent over to please Grogan and Barr instead of supporting them.

The two took their cause to the Dallas Police Association, which loaned them $10,000 to pursue their lawsuit. (The DPA also gave Walker $5,000 outright, but refused to give Rollins an additional $5,000 to fight the suit.) Their suit was later joined with a lawsuit filed by the Brutons, who added Southwestern Bell to the list of defendants. The couple has since divorced.

Jan and Richard are not the only ones trying to figure out what happened. “John Barr thinks he’s above the law,” says one former investigator who worked on the case. “I’m not sure he’s not. I don’t understand the DA’s office, the police department. They’ve got a lay-down case. The phone was obviously tapped and John Barr was using the information and so was the police department. [When Barr went to visit Smallwood in jail], he was hindering apprehension and arrest. The police department, the DA’s office, and everybody else let him get away with smooth murder”

Barr still holds his deputy badge, though he no longer runs warrants. He denies any wrongdoing. “I’ve been investigated twice by the State Bar and cleared,” he said in an interview with D. Barr says he had to go to Internal Affairs to file his complaints; he would be violating state law if he withheld knowledge of a crime. But he admits that he had ignored wrongdoing by officers in the past. When asked why he didn’t file complaints against them as he did against Jan, Barr hastily explains that he meant minor infractions like running stop lights.

“What would my motive be to do all this?” Barr asks. After all, he says, the water commission’s investigation had ended; the owner of the landfill, not his client Grogan, was fined for the barrels.

In Barr’s view, Richard should have arrested Smallwood for the Grogan burglary regardless of the risk to the undercover operation. Or, if not that, police should have come to Grogan and told him that a larger federal operation was involved. He ignores the obvious conclusion: why would police tell one of Barr’s clients about an undercover operation? Barr had threatened to tell Channel 8 that Bruton was a confidential informant months before the burglary, threatening the officers’ cover. A policy memorandum issued in August by Rollins, who jumped three ranks after Mack Vines’s arrival, stated that undercover officers are not bound to stop a crime in progress, unless death or serious injury could result, if it could expose their operation. In other words, Richard and the DEA handled the burglary situation the right way.

Smallwood, perhaps not surprisingly, has changed his story. After telling his original story in a letter, an affidavit, in person to an FBI agent, and to an investigator with the DA’s office, Smallwood has now signed a contradicting affidavit saying he knew Jan Forsyth was a cop all along.

If that’s true, why did he offer to snitch on “Diane” and “Joe Bob”’ when he was arrested, and why did he continue to set up Bruton with his boss Coltharp? Both Smallwood and his girlfriend agreed to testify that Bruton “masterminded” the burglary of Grogan’s house. Why, then, did Bruton call Richard while the burglary was in process?

In the police department, rumors about what happened to Jan and Richard abound. Walker and Rollins have testified in depositions that they wanted to continue to monitor the phone in order to see if they had corrupt officers. Certainly uncovering dirty cops for people like Grogan and Barr would enhance careers, especially with a new police chief.

According to testimony from his own officers. Mack Vines was thoroughly briefed on the wiretap and the complaints against Jan Forsyth that were based on information from the “magic” telephone. If that is true, say two former assistant district attorneys, Vines could be indicted for “misprison”-concealment-of a felony. (Vines declined comment, citing pending litigation.)

If nothing else, Vines is guilty of baffling indifference to problems in his department. In a deposition taken in a state “whistle-blower” suit filed by the officers against the city because of their transfer, Vines says he never bothered to read all of the IAD report on Jan, and says he remembers little about the incident in which his own officers and federal agents were exposed, possibly by those in his own chain of command.

There is evidence that Vines has nodded at the wheel before. A grand jury convened last year in Cape Coral, Vines’s previous command, indicted a police lieutenant and a former narcotics officer for misconduct that began during his tenure. The grand jury blamed an indifferent management-including Vines-they said was “abject and [in] complete dereliction of duty.”

It may never be known who connected the two telephone lines of the Dulworths and the Brutons. John Weekly, a public relations expert hired by Barr and Grogan to handle the aftermath of a story that appeared in The Dallas Morning News, admits that both Barr and Homer Dulworth, who once worked for the phone company, were capable of putting on the tap, but he denies that either was responsible. Homer Dulworth says he passed a polygraph test about the wiretap arranged by his attorney.

Bobby Woods, a drug dealer now in the penitentiary, told D Magazine that Joyce Dulworth began calling him in July or August 1988, telling him all that she heard on the phone. A federal agent who talked to Woods says that he was told that Gary Dulworth “was part and parcel” of the wiretap.

During an interview in prison, Woods said he told the FBI that if anyone tapped the phone, it was an associate of Coltharp’s named David Evins. Evins, who had fixed Woods’ telephone and stereo, was a friend of Gary Dulworth’s.

Evins was arrested at Bruton’s farm on September 12 for driving a truck stolen three months earlier, probably by Smallwood, from a man who worked for the phone company. The truck’s owner says that he kept a handful of plastic connectors, like those found at the Dulworths’, in his truck. At the time of the tap, the connectors were available only through Southwestern Bell. The FBI, supposedly conducting an in-depth investigation, never contacted the owner of the stolen truck. Did Gary Dulworth, still mad at Bruton for testifying against him, ask his friend Evins to connect the two phones?

A sealed indictment of Coltharp was recently returned by a grand jury in Oklahoma. If he is convicted, other agencies will get the $10 million in assets that would have gone to the DPD. DEA agents are furious. What the higher-ups in the Dallas police department did “sucked,” says one undercover federal agent. “We were exposed.”

The feeling among undercover agents all over the city in support of Jan and Richard is such that even though they were ordered explicitly not to talk to D Magazine, several of them called on their own to express their displeasure with Vines and the DPD.

Ironically, in the middle of all this, the FBI’s Gillham gave a special commendation to Jan and Richard after they and Bruton helped set up the arrest of an armed federal fugitive who was wanted for a bank robbery.

Richard has only to make it to November to get his twenty-year pension. “There’s no way my career should have ended this way,” he says. Jan has another three years to go. Thanks to a trust fund left by her father, she doesn’t need her police pay to make ends meet. But she wants to stick it out.

“All my life I’ve been straight up,” Jan says. “I was glad I worked for a clean city. I would take vacation time if I was sick with the flu. I was a dummy.”

She doesn’t understand why Barr went after her, and why her supervisors let him get away with it. Jan sighs, shakes her head: “It’s just not right what they did to me. I would be in the federal penitentiary if I did it. There’s no check system in the Dallas Police Department.”

Jan has lost not only the work she loves, but her impeccable reputation. Somebody, she says, will always believe there was something corrupt about her or she wouldn’t have been investigated. “You know they think about it. they wonder,” Jan says angrily.

Charlie Bruton is in jail, awaiting trial on unrelated charges. Like almost all confidential informants, he lived a life on the edge of drugs, violence, and crime. But for all his faults, for all his excesses, Bruton was trustworthy in his own way, Jan says.

“Running narcotics search warrants is the most dangerous thing you could do,” she says. “I’d run through a door faster with Charlie Bruton than the chiefs. It’s a sick feeling to know you’re out there by yourself.”

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.