As much as anything, Greg Metz wanced to see how Rick Brettell would react. They were sitting in Brettell’s small, sedate office, surrounded on two sides by walls lined with books on the greats-Pissarro, Monet, Picasso, Chagall-at the Dallas Museum of Art, where Brettell had been director for a little more than a year. ■ The performance artist and the museum director were flinging ideas at each other with rapid-fire intensity, trying to come up with a way to commemorate “A Day Without Art.” Held on December 1, 1989, it was a national effort by the art world to draw attention to the devastating impact of AIDS on the creative community.

Metz, who is well known for outrageous installations like “Reagan’s Temple of Doom,” mounted during the 1984 Republican Convention, and “Dr. Caligari’s Ark,” an anti-vivisection sculpture, had first met Brettell several months earlier. The artist, who is president and cofounder of DARE (Dallas Artists’ Research and Exhibition), an activist artists” group, had visited the museum director in his office. Brettell, dressed in a tuxedo, had hauled the rail-thin Metz, whose raggedy work clothes were covered with paint and turpentine, downstairs to the black-tie opening of the museum’s Impressionist exhibit.

Surrounded by Dallas’s glitterati, Brettell pulled Metz from Monet to Manet, explaining what he liked about each painting. “It’s that kind of enthusiasm that’s catching,” says Metz. But he was aware that Brettell was secretly delighting in the spectacle they made-the tuxedo and the rags. “People were staring,” Metz says. “I was wondering, “Is this guy a nut?’”

Now, in Brettell’s office, Metz tossed an idea out like a challenge. Brettell obviously wasn’t a snob, but Metz would find out how far the museum director’s commitment to real art by live people extended.

“Why don’t we make a giant black condom and lower it over the Hyatt Regency tower?” Metz suggested. The image of a gigantic prophylactic looming over the skyline of Dallas would certainly be a powerful artistic statement, and besides that, it would probably make the national press. The artist expected Brettell to hem and haw, then come up with excuses to scuttle the idea.

But without blinking an eye. Brettell said: “Let’s do it. Who do we call?”

His enthusiastic response caught Metz off-guard. “I said, ’O-kaaaayy.’ I just threw it out there to see where the guy was. If there had been a logistical way to do it, he would have done it.”

Ultimately, the project proved impossible. They never even got far enough to confront the inevitable political issues involving the Hyatt Regency management, not to mention the museum’s board of trustees.

Would Brettell really have done it? Or, in a microsecond, with his legendary ability to go from point A to point E without touching on B, C, and D, did Brettell realize that there was no way this idea would, literally, get off the ground? By agreeing and letting the concept play itself out, he would win the respect of Metz and other local artists, something Harry S. Parker III, the previous DMA director-conservative and traditional-never even attempted to do.

The truth is probably both: Brettell knew the condom scheme would go nowhere, but wished it would. Under the exterior of the urbane scholar, the Renaissance man who plays piano beautifully and loves the opera, the symphony, and great literature, lies the heart of an imp. Like a naughty Caravaggio who infuriated the pope by insisting on painting his Madonnas without shoes. Brettell is a rebellious baby boomer who charmingly, engagingly thumbs his nose at the so-called authorities even while they are eating out of his hand. When the DMA board hired this preeminent scholar of 19th-century painting to lead the museum into the 21st century, they definitely were not expecting giant condoms.

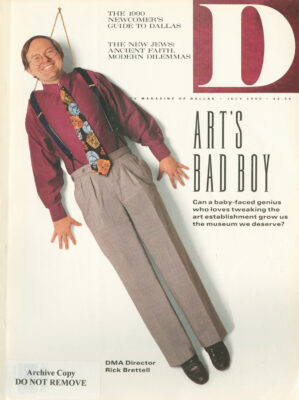

After weathering two years of controversy, usually created by Brettetrs penchant for saying exactly what he thinks, the forty-one-year-old director is embarking on two great projects that will profoundly change the way Dallas views art. One, the new Nancy and Jake Hamon Building, is close to becoming reality. The other, the experimental Hickory Street Annex, still is in the formative stages. But he’s facing astronomical odds. The truth is, Brettell is the head of a civic museum with one of the puniest endowments in the country, relying on operating funds from a City Hall where differing factions fight for every penny.

With profound political changes coming, the question is, can Rick Brettell-a white, Yale-educated male-bring a kind of democracy to the DMA, an institution with a reputation as a haven for the elite?

Craig Holcomb, chairman of the city’s Cultural Affairs Commission, thinks so. He tells an oft-repeated story of Brettell’s driving around Dallas with black city councilwoman Diane Ragsdale. “He ended up sitting on her floor talking about Dallas all night,” Holcomb says.

Bret tell likes (he story and knows it’s made the rounds. The only problem, he laughs, is that it never happened. The two had gotten acquainted during the formal festivities surrounding the DMA’s “Black Art-Ancestral Legacy” exhibition. That show, along with the “Images of Mexico” exhibit, were both held within Brettell’s first year as director. Though the African-American exhibit was scheduled before his arrival, the way the two exhibits were handled sent powerful signals that Brettell was interested in and committed to minority art and culture. Later, he saw Ragsdale at a Dallas Black Dance Theatre performance. The councilwoman impulsively threw her arms around him and planted a big kiss on his cheek.

Brettell smiles mischievously at the memory, his eyes crinkling behind round tortoise-shell glasses. “She’ll deny it, but for me it was really important. It was like being kissed by the Virgin Mary.” Brettell throws back his head and laughs uproariously.

THE CARESSES THE CANVAS LIKE A MAN touching a lover: “The light, the way the waves crash.. .” On loan from a West Texas family unnerved by a recent record art heist, “The Wave” by Renoir hangs in his office. He will soon meet with the family to determine if there is any way the Renoir and a number of their other Impressionist paintings, worth millions, could come to the museum as a gift.

If it happens, it will be one of the most important donations ever made to the museum. Brettell is thrilled by the possibility but also aware of the precariousness of the situation. One of the most difficult jobs of a museum director is persuading people to part with cherished objects. The task is often accompanied by tears and much emotion as collectors confront their mortality.

But “passion undergirded by intellect” makes Brettell very appealing to donors, says Vincent Carrozza, a former museum trustee who was on the search committee that brought Brettell to the DMA. Serious collectors want to know that the museum director truly understands and appreciates the art they have poured their lives and money into accumulating. *i think you will see some very substantial contributions to the museum in the next few years,” Carrozza says.

Brettell is the first true scholar to be chosen as DMA head. Started in 1903, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts had twenty-one members and didn’t even have a director until 1929. In 1963, under the aegis of artist-director Jerry Bywaters, the DMFA fused with the more rambunctious Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts. It became the Dallas Museum of Art in 1984 when it moved to its current downtown site.

For most of its history, the museum was located in Fair Park, where shifting demographics and white fears about the safety of the mostly black neighborhood led to sagging attendance in the Sixties and Seventies. In 1973, the museum’s board of trustees turned the reins over to Harry Parker, an up-and-comer in the New York Metropolitan Museum’s education department. Parker’s mandate was simple; get the museum out of Fair Park and into the downtown business district.

And Parker succeeded brilliantly. After an initial setback, Dallas voters approved a $25 million bond issue in 1979 to create what many see as the jewel in Dallas’s civic crown: the Edward Larrabee Barnes-designed building at Ross and Harwood.

After fourteen years, Parker was ready to move on as the Eighties drew to a close. Though he had staunch supporters on the board, he also had his detractors, who saw the museum as losing momentum after the new building became a reality. They felt Parker was too rigid, too conservative to generate the excitement museums need today to compete with the pervasive entertainment industry. According to one board member, Parker wanted to return to the East Coast and applied for the job as director of the Boston museum. When he didn’t get the position, he asked the DMA board to renew his contract. They politely declined.

In mid-1987, when Parker announced that he was moving to San Francisco to become director of that city’s Fine Arts Museum, the DMA board appointed a handful of trustees to a search committee. They began interviewing every museum director in the country- not so much to determine who they should get, but to learn what kind of person they needed.

The trustees knew that the head of a museum with 180 employees and an annual budget of $10 million would have to be psychologist, sociologist, diplomat, and financial wizard. But above all, they learned, in the frenzied art market of the Nineties, he or she must be a scholar, with the ability to build collections from a strong base of knowledge. The problem was, top scholar-administrators are “not floating around.” says Betty Blake, who was on the search committee.

As Searle Curator of European painting at The Art Institute of Chicago and a former professor at The University of Texas. Bret-telTs name came up late in the process. He was known for bold exhibitions, especially a record-breaking show on Gauguin, and for being a prolific writer and an exhilarating lecturer. Brettell was also regarded as somewhat eccentric, unorthodox. He had recently mounted an exhibition of nothing but frames.

Trustees Vin Prothro and Roger Horchow visited Brettell in Chicago. “I personally knew in five minutes he was the right person,” Prothro says. L’I developed a single question [during the search]: tell me what art pieces you have acquired in your current job, and why. I didn’t pay much attention to their answer but to how long they talked about it. With Rick, it was an hour. He is better able to articulate the excitement of art than anybody in the country.”

Brettell’s experience as an educator appealed to the trustees. “And he wanted the job.” Prothro says. “I stopped worrying about Rick and started worrying about Caroline.” Caroline Brettell, a highly regarded anthropologist, was a scholar at The Newberry Library and visiting professor at Loyola University. She had made several moves in the past to advance her husband’s career, and she did not want to leave Chicago just as her own career was taking off.

But the trustees discovered an opening for a visiting associate professor in the anthropology department at Southern Methodist University. “Her resume on paper is more impressive than Rick’s ” says one trustee. Caroline got the job, and in early 1988, the Bret-tells moved to Dallas, At thirty-nine, he was the director of the DMA with a salary of $150,000 and responsibility for more than $250 million worth of city-owned art.

“The reason I came here is that I firmly and fundamentally believe in the great American tradition of the civic art museum, of the people’s museum, rather than ’The Frick,” ’The Kimbell,” ’The Norton-Simon,”” Brettell says, ’it’s not that there’s anything wrong with the donor museum, but it always sort of wears its donor as a shield. A city museum has to deal with art in a much more complicated and ultimately much more satisfying way. And I love the sense that the Dallas Museum of Art wasn’t named for anybody. And that it was a public-private partnership.”

Oddly, Brettell’s own field, European painting, is widely considered to be one of the DMA’s major weaknesses. The DMA has built up tremendous collections in African and pre-Columbian art, and with the acquisition of the Faith P. and Charles L. Bybee Collection of American Furniture has launched into the decorative arts in a big way. But there is a significant gap in the European collection, a gap that many experts believe prevents the museum from leaping into position as a major institution, not just a highly regarded regional museum. Of course, as Brettell is aware, there are those who would not even give the DMA that modest accolade.

“Rick is by far the best-educated, the most brilliant director the museum has ever had.” says a curator who has worked at several major museums. “It is not too late to save this museum. It’s a museum that’s basically boring.”

The DMA trustees knew Brettell’s reputation as a genius with an abrasive side. If he can mesmerize 1 isteners with a discourse off the top of his head about almost anything, Brettell can also infuriate the thin-skinned with his habit of saying exactly what he thinks, at the moment he thinks it.

Within three weeks of his arrival, that trait firmly planted Brettell in a controversy that dismayed some-and delighted others- when he suggested, out loud, that perhaps the Wendy and Emery Reves Collection of paintings and decorative objects, now ensconced in a series of rooms re-creating her European villa, did not warrant all the constraints the DMA agreed to in order to land the collection. Never before had the DMA bent its policy against allowing collectors to dictate how works should be shown. In the case of the Reves Collection, the museum agreed to exhibit the artwork only in this “’villa” setting. The result is that some of the important pieces must be viewed from a distance, and only rarely are individual pieces allowed to be shown with other exhibits.

Wendy Reves, who heard about his remarks in Europe, fumed. Others quietly agreed with Brettell.

One local curator derides the collection, saying, “Here comes Wendy Reves, looking for a way to memorialize her husband and herself. I think Harry [Parker] felt so keenly this lack of depth of European paintings that he allowed himself and the board to compromise. The installation is distracting and hard for the public to see and appreciate the art. Anyone would want to split up the collection. It should be done. It was perhaps impolitic of Rick to blurt that out. But it is proper for him to want to do it.”

The close relationship that Parker had enjoyed with Mrs. Reves also made it difficult for Brettell. “Harry [Parker] was her white-haired boy,” says one trustee. “When he left, she was furious.” Brettell, for his part, admits he didn’t understand the history of the Reves collection coming to the museum. (One source says that Parker shredded all but the official documents concerning the DMAs acquisition of the $35 million collection. Asked about the alleged shredding, Brettell looks like he’s been offered a live cobra. “I don’t even want to say, ’no comment.’”)

After the Reves backlash, Brettell flew to France with Harry Parker to patch things up. “Mrs. Reves is one of the great characters of the 20th century,” Brettell says. “’She had a special and personal relationship with the director of this museum. When somebody comes in and takes the job, the relationship doesn’t go with it. You start all over again.

“I’m very blunt. I usually say what I think. It gets me into hot water sometimes, and it’s very good other times. I’ll never change. But it became clear to me that she had a great deal to teach me, and it became clear to her that I would listen to her. I think she imagined that I was just shooting off my mouth, which of course I was. But so was she. It was sort of a fun fight, inaway. Ithinkweeach got a certain amount of pleasure out of it.”

THE FIRST SIX MONTHS OF THE BRET-tells’ time in Dallas brought one controversy after another. An avalanche of letters accusing Brettell and the DMA of pornography followed the Kiki Smith exhibit, which featured paintings of body parts on glass. Though the exhibit had been initiated before he arrived at the DMA, Brettell stood behind it, writing each correspondent a personal reply.

“NOW/THEN/AGAIN” an exhibit of contemporary art, also drew fire, especially because Brettell had the carpet ripped up, leaving the rough concrete underneath exposed for a raw effect. “What people didn’t understand was that the carpet needed to be replaced anyway,” says Gary Cunningham, the architect hired to design the exhibit.

Some art lovers deplored the way the exhibit was handled, with one calling it “execrable.” Singled out for particular scorn was the “baseball mitt” chair hung on an arm-like extension that seemed to break through a wall. But the show brought in an audience of those in their twenties and thirties, a group notoriously hard for the museum to attract.

As Brettell shuffled the staff, the docents became irate over his treatment of the venerated Dr. Anne Bromberg, a brilliant lecturer who had been the head of the education department for years. “Anne was being ignored and phased out without anyone’s saying anything deliberately,” says one longtime docent. “All one hundred docents were screaming with rage. He’s a young man. He didn’t think it through. He was more amazed than anyone that he had stirred up such a hornet’s nest.”

Another docent, Rebecca Goldthwaite, says that despite the turmoil, the changes Brettell has made are positive. Dr. Bromberg continues to lecture, but the docent program has a new focus, “He wants us to engage the audience in conversation,” Goldthwaite says. “We’ve been retrained radically to stimulate the audience with provocative questions.”

Brettell says the thing that made his first six months in Dallas most difficult, however, was not controversy. It was money. The endowment at The Art Institute of Chicago is $110 million; the Houston Museum of Art, no Louvre, has $90 million. By comparison, the DMA’s endowment is a paltry $12 million.

“That’s a shocking statistic,” he says. Brettell knew the DMA’s financial condition before taking the job, but he says he did not realize how difficult that and the current crunch in the city budget, which provides 15 percent of his operating funds, would make it to run the museum. Occasionally, the museum has a hard time meeting the payroll, and he confirms the rumors that small suppliers often do not get paid on time.

But Brettell says Jean Folwell, the museum’s financial director, has made order out of the fiscal chaos he found when he arrived. Increasing the endowment to $100 million by the year 2000 is one of Brettell’s most important goals.

As DMA director, Brettell lobbies City Hall for operating funds, a task that promises to be more difficult than ever when a new City Council almost certainly brings a higher percentage of minorities. Faced with constituents who lack necessities, minority council members may be reluctant to pledge more to cultural affairs.

Brettell thinks he can work within that system; indeed, his uncanny political instincts led him to anticipate that shift and build bridges in advance.

“The so-called minority community has been really important to me,” says Brettell, pointing to the success of “Images of Mexico” and “Black Art-Ancestral Legacy.” “I’ve made very good friends. Though there are real racial problems in the city, it’s so much better than the old cities in the Midwest and the East. There’s no sense in Chicago that the white liberal community and the blue-collar community and the black community and the Hispanic community will ever come together.”

It’s somewhat ironic that Brettell-a white, Ivy-League-educated scholar of European painting who never knew an African-American until he was sixteen-may be one of the few people in Dallas ideally positioned to help bring an age of cultural awareness and harmony to a city racked by severe racial tension. And it’s ironic that he, an outsider, is among the most hopeful.

“The number of people I know who feel a part of the museum, a part of the community, is much greater here than anyone had in an analogous institution in Chicago,” Bret-tell says. “There, the ghetto is the ghetto is the ghetto. The divide is much greater. Here, there is a lot of openness. There are a lot more people here that think it can work.”

DURING THE SUMMER OF 1966, RICK Brettell committed his first and only felony: he broke into the abandoned house across the street from his dormitory at the University of Chicago.

Along with a group of extremely bright teenagers from across the country, Brettell was spending the three months before his senior year in high school studying biophysics. It was the first time he had been on an airplane, the first time he had been in a large city. He loved walking around Chicago looking at the architecture, though he knows he must have looked like a teenage snob-in-training. “I was a pushy little creep,” he says, laughing. But at sixteen, Brettell knew a Frank Lloyd Wright when he saw it: the abandoned building was The Robie House, one of the American architect’s masterpieces.

So, at an age when other boys were trying to figure out how to get a girl’s bra off with one hand, Brettell broke into a house to study its architecture. “It was wonderful,” Brettell says. “I analyzed it, walking around seeing how the light worked.”

Brettell had grown up in suburban Denver, playing baseball and soccer, climbing trees, and grubbing in the canal behind his parents1 home like all the boys in his neighborhood. But he always knew he was smarter than the other kids.

“I remember Sputnik very well,” he says. “Suddenly everyone was taking math and science very seriously. We were behind and we had to catch up. I was very good in science and math; in feet, better than I was in humanities.”

But he was always involved in cultural pursuits. He sang in the opera chorus of “Samson and Delilah” at age twelve. “I wanted to be a serious musician instead of a little piano student in the suburbs, which is what I was,” Brettell says. But he decided early on not to pursue a musical career. “That wasn’t enough,” Brettell says. “To me, that was what someone did as part of one’s life.”

That summer in Chicago, he studied science with award-winning professors. He heard Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahalia Jackson in the park. He and a group of other students formed a baseball team they modestly called “The Young Geniuses” and played a version of urban baseball with the Blackstone Rangers, a black street gang.

“It was absolutely glorious,” says Brettell. “It was the first time I made friends with black people. We went to their houses, so many of my white middle-class mythologies went out the window.”

Intending to study biophysics or some other form of science, he applied to Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and the other great universities. He was accepted to them all, though he was crushed by being put on the waiting list at Harvard. While Columbia promised a full scholarship, he pushed for Yale because it had a reputation not only for science, but the humanities. His parents, though not wealthy, finally agreed.

Yale in the late Sixties was undergoing dramatic change. The student body, still all-male, rebelled against the stuffy dress code and got it abolished. And the university’s admission policies were changing, bringing in students from all over the world. The Black Panther trials were being held in New Haven. “It [Yale] was absolutely alive,” Brettell says. He wrote for the Yale Journal, which he describes as a “pseudo-high-brow poetical and critical journal.” Brettell’s first piece was a scathing attack on architect Edward Larrabee Barnes’s design for the undergraduate library at Yale.

Because he placed out of many required science and math courses, Brettell filled his extra time with humanities classes. During his sophomore year, he went home and announced that he was going to major in philosophy, a plan that was met with horror, then resignation on the part of his parents. After all, this was a time of rebellion.

An art history class, complete with large, clear slides of all the wonderful masterpieces Brettell had seen in black and white in one of his mother’s old art textbooks, changed his direction again. “They were revelations,” he says. “You’d walk out of the lecture to a beautiful day and look at everything differently. It was as if your vision was transformed.” He now determined to major in art history and become an architect.

Before deciding which graduate school to attend, Brettell landed a teaching fellowship at Yale. It was generally agreed that allowing someone with a mere bachelor’s degree to teach was absurd, and only one professor would take him on. Unknown to him, the teacher who got him wasn’t going to let him teach either-until she came down with a severe case of laryngitis. His first lecture was on Pissarro; his professor listened and critiqued his lectures with a croaky voice and scribbled notes.

“Nobody ever gets that,” says Brettell. “It was great. I decided there was something of the preacher in me. I wanted to convince people there were great and beautiful things in the world and we shouldn’t forget them in our rush for power and money.”

Abandoning the idea of becoming an architect, Brettell stayed at Yale for his master’s and doctoral degrees in art history. After marrying in 1973, he went to Paris for a year, then Portugal for six months in order for his wife to pursue her studies.

The Brettells returned to the United States in 1976; he was offered assistant professorships at four universities. All paid similar salaries. They chose to go to The University of Texas at Austin because of the school’s library, not because of any affinity for Texas. In fact, like many Coloradans, Brettell thought the Lone Star State was a bit ridiculous-all those loud-mouthed Texans in expensive ski clothes. “I grew up to hate Texas,” he says, “but I had never been there.”

Brettell quickly became a legend on the UT campus. “The kind of ardor he inspired in students was unbelievable,” says Lisa Germany, a writer who graded for Brettell at UT. “He made people interested in art who had never been interested before.”

She remembers a class in which Brettell showed the students an engraving of “Gin Alley” by Hogarth. Brettell accompanied the disturbing image of the social abuses of the late 18th century by reading William Blake’s “London,” a poem that perfectly captured the picture’s despair.

“When he finished, it was like he had almost forgotten the class was there,” Germany says. “He was just silent. The impact was incredible. The class jumped to its feet and applauded.”

AFTER TEN YEARS AWAY FROM THE academic world, Brettell, in a way, has returned to education. But now, he’s trying to teach more than a million people. A joking testament to his responsibility lies on the conference table in his office: two rubber stamps, “This is art” and “This is not art,” gifts from a friend.

“It’s easier to educate fifteen graduate students than a whole city,” Brettell says, “to make them aware of the cultural glories that are theirs. There is so much that is wonderful here. I’ve learned that Dallas is a richer and more complex city than it thinks it is. There’s much more here to be proud of than people realize.

“And that’s something I don’t quite understand. There seems to be a desire on the part of people here who are interested in high culture to apologize for the institutions that have been created, that they have created.”

Brettell describes a survey taken in New York and Chicago asking people to evaluate their art institutions. New Yorkers rated the Metropolitan Museum third in the world, behind the Louvre and the Prado. Chicago rated the Art Institute number one. He laughs, delighted; neither survey showed anything about art, only about each city.

But educating a city is impossible one-on-one. For better or worse, Brettell wants to take this sense of excitement and discovery to his biggest audience ever. That involves much more than using his personal charm and knowledge as the master teacher.

It means shoring up the DMA’s endowment. It means working with City Hall and local school districts. It means inspiring a curatorial staff to reach new heights of achievement and making the museum reach out to the community more than ever before.

One of the first tasks he tackled after arriving was attempting to talk philanthropist Nancy Hamon out of giving $20 million to the museum for a new wing. Instead, he wanted the money to go to acquisitions, education, and programming.

Hamon patiently gave him a history lesson, he says. The museum was full; acquisitions were coming in all the time. The museum needed the building. So Brettell is working on the plans with architect Barnes, whom he has described as “the quintessential New England WASP.” (One of the first things he did after coming to Dallas was to jokingly send Barnes a copy of his early critique of the Yale library.)

Brettell also is quietly pushing another building project: the Hickory Street Annex, a collection of several buildings in Deep EUum that he sees as an off-site extension of the museum, a place to show contemporary art that might not be appropriate for the downtown museum-shows that could bring in younger audiences and act as a bridge to South Dallas and the Fair Park area.

Though it would take several million dollars to make the buildings usable, and at least $320,000 a year to operate, Brettell doesn’t see the money as an insurmountable problem. The big effort will be getting a consensus that it’s a good idea.

“I’ve learned a lot from being here about that,” Brettell says. “Some decisions you can do in camera, alone, quickly. Other decisions need to be made slowly, with a group. It’s a messy decision-making process, but the result is better.”

Though Brettell will certainly remain controversial in some ways, pushing the envelope of the traditional art museum, he will probably not go as far as some supporters would like. For instance, Brettell says he would not bring to the DMA the homoerotic work of Robert Mapplethorpe, which caused the arrest of a museum director in Cincinnati. It certainly is art, Brettell says, but it is not suitable for a civic museum.

His early announcement that the DMA will concentrate on building its collections of art from South, Central, and North America has caused some unrest among some powerful Eurocentric patrons. But Brettell has brought in some major European art, such as an anonymous gift of Rembrandt etchings. And if he is successful at negotiating the girt of Impressionist paintings from the West Texas family, the DMA’s gap in European painting will have narrowed considerably.

While supporters are glad that Brettell has weathered the early controversy and is leading the museum in the direction he wants, they worry. How long will this “brilliant, brilliant man,” as one puts it, stay in Dallas? The DMA has no contract with him. His wife is in the middle of a four-year professorship, and Wendy Reves reportedly is on the rampage again, demanding that the museum return a portrait of her that was included in the donation. Still, he’s optimistic.

“Whenever I do something I think I’m going to do it forever,” Brettell says. “It’s possible I’ll be here ten years. It’s possible I’ll be here the rest of my life. 1 can’t not see things through.”

He believes that when the Hamon wing opens on Columbus Day in 1992-with, he says, the greatest permanent installation ever mounted of art from the Americas-the museum will be “if not revolutionary, then fundamentally different. I think that it might well be the most intelligent museum since the war.”

The thing he misses most in being a director is the time to lecture and write. He just finished a book on Pissarro and wants to write one on Gauguin’s texts. “The difficulty of what I do now is that I’m not really in control,” he says. “My time is scheduled by so many other demands. That’s hard.

“But you have to grow up sometime.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Commercial Real Estate

What’s Behind DFW’s Outpatient Building Squeeze?

High costs and high demand have tenants looking in increasingly creative places.

By Will Maddox

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 2

It's time to start worrying.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo