As the camera pans shakily around the poorly lit living room, the police video at first seems to be little more than a bad home movie of a messy working-class house. But as the viewer takes a vicarious walk through the small house on Miguel Lane in Arlington, hearing the muffled voices of policemen, some hints of the horror from that night appear. Spots of blood on a telephone. A bloody sock near the fold-out bed. Droplets of red trailing across the linoleum in the kitchen. And even these premonitions do not blunt the shock of seeing the bodies.

Seventeen-year-old John Bradley, body stiff in rigor mortis, wedged on the floor of a small laundry room, gagged with a white bra, hands and feet tied, stab wounds plainly visible in his neck and chest. Twelve-year-old Renee Lemieux, hands and feet bound, curled in a fetal position on the bathroom floor, nestled in a pool of gore. And in the master bedroom, fourteen-year-old Danielle Lemieux, gagged, hands bound behind her back, face down on a waterbed, partially covered with a white sheet. Her panties dangle off one leg. Blood seems to be everywhere.

It was the responsibility of Arlington’s Major Case Unit, a group often investigators assigned to difficult investigations, to find out who brutally murdered the Lemieux girls and John Bradley on June 17, 1985. The officers walked through the house, sweeping, dusting, measuring, photographing, and bagging evidence, like archaeologists on a dig. Some of the officers, stunned by the scene, hurried outside to throw up.

In April 1989. four years and three trials later, Ronald Steven Trimboli, a chef and second-generation Italian, son of a Boy Scout administrator, was convicted of the murders and sent to the penitentiary, where he will not be eligible for parole until he is more than one hundred years old. It was one of the most sensational murder cases in Tarrant County, second in expense only to the trials of T. Cullen Davis-and one that ten years ago might have never gone to court, much less resulted in a conviction.

How Trimboli was identified as a suspect, arrested, and finally put away is the stuff of books by Joseph Wambaugh, the essence of novels like Presumed Innocent. It’s the story of police detectives wearing out shoe leather-then using arcane, controversial, hightech investigative techniques to confirm their gut instincts.The FBI profiler said the killer would be a neighbor who was familiar with the Lemieuxes’ home and their routine.

Some of the new tools are simply new methods of gathering evidence, such as videotaping the crime scene and blood spatter analysis. But other, more sophisticated techniques go to the heart of the crime.

One technique, called “criminal profiling,” is used frequently in sexual homicides. Developed by the FBI, the technique works backward from the forensic evidence to describe the personality of the killer, then gives investigators tips on how to elicit confessions. Its success rate is surprisingly high.

But the most sophisticated technique of all-and the one that promises to have the same kind of revolutionary effect on law enforcement that fingerprinting did in the 19th century-is so-called “genetic fingerprinting,” a tool that proponents say can identify a guilty party with overwhelming odds in some cases, better than a billion to one.

Working on the premise that each individual’s DNA-deoxyribonucleic acid, the genetic material found in most living cells in the body-is utterly unique, the test might match semen found at a crime scene with the blood of a suspect, or the blood found on a knife in a drawer at the suspect’s house with the victim’s blood. If conditions are right, scientific “sheriffs” can pin the deed on the right man or woman 100 percent of the time, proponents say. leading law enforcement agencies to eagerly anticipate the day when DNA prints of known killers and sex offenders will be on easily accessible computerized files.

“This is not like finding the fingerprints on the gun, stresses Dr. Robert Benjamin, a molecular biologist at the University of North Texas. “This is like finding the fingerprints on the slug dug out of the body.”

“Genetic fingerprinting” nailed Ronald Trimboli. But nationwide, controversy has erupted over the way the “infallible” test is performed and interpreted. The answers that emerge from the scientific squabble now raging in laboratories around the country may affect how criminal investigations are handled from now until the 21st century.

•••

Joanne Lemieux and her two daughters were thrilled when they moved to Miguel Lane from the Diamond Tree Apartments a few miles away. The rent was about the same, and now they were in a stable, working-class neighborhood where well-kept brick duplexes lined the street. Their two-bedroom unit sat on a cul-de-sac.

Recently divorced, Mrs. Lemieux was struggling to provide for herself and her children, fourteen-year-old Danielle and twelve-year-old Renee. She worked long hours, sometimes from 8 a.m. until 11 o’clock at night. “It was important that I bring them up in the way they were accustomed to when we were married,” Joanne later said, though her hours meant the girls were frequently unsupervised. The Lemieuxes were happy on Miguel Lane, so happy that they told their friends who still lived in the apartment complex about the street. At least one family, the Trimbolis, took Joanne’s advice and moved into a duplex about eight houses down on the corner.

The Lemieux sisters’ room reflected the interests of many Arlington youngsters on the cusp of adolescence. Girlish pink and white spreads on the beds contrasted with the heavy metal music posters on the wall. It was summertime, June 1985, and that meant sleeping late, listening to music, and having fun with friends.

Hope Tolle, Ron Trimboli’s stepdaughter, was Renee’s best buddy. Renee frequently played at Hope’s house, and the girls would occasionally spend the night together. But dark-haired Danielle, who police would later describe as “older than her years,” was firmly into teenage turmoil, writing an adolescent’s version of what it meant to be hip and grown-up in another friend’s junior high yearbook: “’Sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll. Drink a keg, smoke a bowl, summer’s here, the school year’s past, time for sex, drugs, and having a blast.” Attorneys for Trimboli would later allege that Danielle’s friends were involved with cocaine and Satanism.

But from most accounts, Danielle hadn’t gotten into drugs or alcohol. And she seemed to enjoy the Friday teenage fellowship time at Trinity Church, which the Lemieuxes had recently started attending.

That’s where the Lemieux family, in May 1985, had met John Bradley, a seventeen-year-old boy who had been living on his own after being kicked out of his parents’ home. For three months, he had been living with Peter and Sharon Dreyfuss, who attended Trinity. They had met him during an evangelistic “outreach” at Forum 303 Mall.

Later, the Dreyfusses would say the stories Bradley told about why he had left his home were contradictory. Though he claimed his stepfather had died, they found that wasn’t true. And though Bradley admitted to the Dreyfusses that he had had a drinking and drug problem in the past, his current struggles centered around sex.

When the Lemieuxes saw Bradley at Trinty on June 14, he and the Dreyfusses had agreed that he would move out. It was obvious on that Friday night, Dreyfuss would testify, that Bradley and Danielle were attracted to each other. When Joanne Lemieux invited Bradley to come stay with her family, Dreyfuss advised against it, suspecting he knew that Bradley’s motive was to seduce Danielle. But Mrs. Lemieux was determined to offer the homeless boy a bed, at least for a short time. “He had nowhere else to go,” she would later testify. He came for a lasagna dinner on Saturday night. On Sunday, he stayed, sleeping on the pull-out sofa bed.

•••

The police arrived on December 20, 1985, when Ron Trimboli was at his parents’ home, at the sink prying open shells for the stuffed clam dish he was making for dinner. He was arrested and taken to jail, where he was arraigned on $150,000 bond and charged with three counts of murder, leaving his parents shaken and infuriated.

“I keep asking myself, why, why?” says Camill Trimboli. Why did witnesses change their stories? Why did police pursue her son relentlessly? “They followed him six months. They would ask his employers about him. He’d lose his job. I had to pay the rent because I signed the lease.” All for a crime he didn’t commit, she says.

Born in Brooklyn in 1944, Ron was raised in a close-knit, second-generation immigrant family. Camill and Rocco Trimboli moved to New Jersey when Ron was eight and his sister was ten. When Rocco’s employer- the Boy Scouts of America- decided to move its headquarters to Irving in 1979, the Trimbolis decided to relocate as well, buying a home in southwest Arlington.

But moving to Texas was the worst thing they ever did, says Camill. In the last five years, her blond hair has turned gray, she says, and the stress has sent her to the hospital three times. Rocco has been diagnosed as having cancer; despite his treatments, he drives four hours each way to visit his son in prison once a month.

Not surprisingly, Ron Trimboli’s parents and family see no pattern of malevolence in their son’s life. Yes, Rocco admits, he was not around much when Ron was young. Forty-five years with the Boy Scouts association kept him working long hours. Maybe he pushed Ron too much in scouts. Maybe that’s why he quit early on. But both parents insist he was never a boy to cause grief. There was the joy-riding incident that wasn’t Ron’s fault. And there was the time she turned him in for using drugs. Just once. “We never had another problem with that,” she says.

The Trimbolis shout over one another as they look for pictures of Ron, carrying on two conversations in Italian accents routed through New Jersey. They recall a happy-go-lucky boy who would buy his friends burgers with money earned from shoveling snow, a handsome kid who was immaculately dressed, who turned girls’ heads wherever he went. “He loved life,” Camill says. “He would always tell me he had to have fun. To him, every holiday had to be a party. He was giving, giving, giving.” There was a conviction for hot checks, yes, but it was the giving. The generous spirit. A little loose with money maybe, but a murderer?

When he was seventeen. Ron quit high school and joined the Naval Air Force. After an accident led to a medical discharge, he returned to New Jersey and married eighteen-year-old Maureen Dalton. He sold cars, shoes, managed a plant store, and, with his wife, opened a dress shop in Newark. But Ron was too generous, his father says- always allowing shoppers to put things on hold for five dollars. “I told him, ’Ron, you’re either going to have to sell it or close.’” Rocco says. “He said, ’Yeah, I guess you’re right.’” After a year, Ron went bankrupt.

Then Ron seemed to discover what he really liked to do: cook. He opened his own food franchises-in a bar, a swimming pool, a bowling alley. But that fell apart when his partner ran off with a waitress, and Ron began working for other restaurants.

When his parents moved to Texas, Ron decided to move as well. His marriage, which produced two daughters, had ended after ten years; he was looking for new business opportunities. His sister also made the move, and eventually Ron’s two daughters came to Arlington as well. One, who is now nineteen, lived for a while with her father. She currently stays with Rocco and Camill. “My dad cooked, cleaned, took care of the children,” says the daughter, who asked that her name not be used. “He was the perfect image of a mother. No way would he do this.”

But Arlington didn’t seem to be the answer Ron was looking for. A restaurant he hoped to open with another investor never got built, so he went back to cooking for others. But he would often be late, or not show up for several days at a time. He was so charming, and such a good cook, that restaurant owners who had fired him would hire him back. “He made the best veal scallopini you could taste,” Rocco says.

In 1982. Ron married Devon, a cocktail waitress in her early twenties that he met at a nightclub. His family says he was working all day and she was working all night; they fought constantly. Rocco says Ron attempted suicide as the marriage disintegrated, then checked himself into an alcohol treatment center. They divorced less than a year later. Then Ron met wife number three, a waitress named Denise. Everyone called her D.C. They lived with her two children from a previous marriage, and in May 1985, D.C. gave birth to Trimboli’s son, who was named Anthony.

On Monday night, June 17, Ron Trimboli joined the people milling around on Miguel Lane, watching as paramedics and police officers descended on the Lemieux home. After calling all day and getting no answer, Joanne had come home shortly after 10 p.m. A few minutes later, after calling the police, she passed out in the master bedroom and was taken out to the front lawn.

From the beginning, it seemed Trimboli was everywhere, talking to reporters, police, and neighbors. “I just kept thinking my daughter could have been down there,” Trimboli told one television reporter. The next day, Trimboli talked to Laura Miller, who was covering the murders for The Dallas Morning News.

“There was a family here just yesterday looking at the house across the street from us,” Trimboli told Miller. “And I was telling them how peaceful and quiet it was here. And now look what’s happened. It’s just unbelievable.’ The girls viewed him and D.C. as their second mother and father, he told reporters; Renee had even sent him a Father’s Day card. In fact, Trimboli went on, he had planned to take the two Lemieux girls to Six Flags Over Texas with his family that day, but the trip had been canceled by Joanne, who told him they were doing something with their father. Joanne would later deny such plans ever existed.

At the funeral for the two girls. Ron hugged Joanne. She came by the Trimboli home the next day, bringing Hope a necklace that had belonged to Renee. But that was before police found Ron Trimboli’s palm prints on the top and side of the dryer. Even before the laundry room floor grew slick with blood, a person standing there, and leaning over to stab John Bradley to death, might have wanted to brace himself by putting a hand on that dryer.

•••

About ten days after the murders, a packet was mailed from the Arlington police department to the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. The packet contained autopsy reports on the victims, crime scene photographs, lab results, and the police report. Investigators quickly realized that solving the first triple homicide in Arlington’s history was going to be difficult at best, and they were bringing in the big guns early: the FBI criminal investigative analysis squad, or in police parlance, the profilers.

The elite FBI squad was created in 1972 when the academy was established and a permanent faculty with credentials in behavioral sciences and abnormal psychology was brought in. It started informally, with students bringing the agents their toughest cases for advice. Today, a staff of ten experienced FBI agents reviews up to a thousand difficult murder cases a year. Over the last six to nine months, the agents have stopped being mere advisers and become active participants in helping prosecutors to get search warrants. They have even started testifying in court as expert witnesses.

“It’s our belief that you can examine the way a crime is committed and draw conclusions about the criminal’s personality,” says James A. Wright, the supervisory special agent who handled the Lemieux/Bradley case. “Everyone’s behavior is driven by their personality. We work backward from the crime to the personality. We have seen so many of these crimes, we have a pretty good idea of the types of people who have been convicted of such crimes in the past. We’re wrong sometimes, but we’re right far more often than we’re wrong.” The FBI has also conducted research by going to prisons and interviewing murderers and serial rapists, building a gruesome data base of crime details available for comparison to other cases.

“For everything done, there has to be a reason,” Wright says. “There’s a big difference between someone stabbed five times and someone stabbed one hundred and twenty times. It tells you the victim was difficult to control or the offender lost control of himself. It might point to the use of alcohol or drugs.”

One of the first things the FBI profilers determine is whether the crime is organized or disorganized. The scene of an organized crime is almost neat, with very little evidence left behind. There are signs of premeditation beyond the obvious fact that a weapon is brought to the scene. A disorganized killer usually makes use of a weapon at the scene and leaves a lot of evidence. The offender often makes an attempt to hide the crime. “That tells you a lot about motivation,” Wright says. But few crimes fit completely into one category or the other.

After examining the evidence, the analyst tries to reconstruct the crime. “Then we try to come up with an explanation for why everything happened the way it did,” Wright says. Finally, they construct a behavioral description of the offender in layman’s terms.

The final report can include from twenty to forty characteristics, which may describe everything from the criminal’s race, age, military service, socioeconomic level, possible physical abnormalities, relationships with the opposite sex, rearing environment, current environment, and work record. Some of the profile is assembled through statistics: for example, homicides of blacks are usually committed by blacks, and whites by whites. “And we know certain types of individuals start killing at a certain age range.” Wright says. Other information is based on the agents experience with similar crimes.

One thing, Wright says, was very striking in the murder of the Lemieux girls and John Bradley. “It had to be somebody who lived very close. It was a person known to these people. The killer was familiar with the place; he knew the mother’s routine. He stayed long enough to have sex. The longer he stays, the more familiar [that means] he was with the place.” And because of the large number of stab wounds, the killer would have been covered with blood; he had to get somewhere quickly without being seen to clean up.The DNA from the bedspread matched Trimboli’s. The odds of a random match were 54.9 billion to one.

The obvious target, Wright says, was Danielle, who was raped. “The young boy was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Wright says. “This is very common when young ladies are raped and murdered. The killer is often very deeply involved in fantasy. He begins to assume something is there that isn’t. He finds a reason to go to the residence, convinced he is going to have sex with her. His perception of her may have been that sex would have come easy for her. She rejects him, he gets irated, and there’s a murder. And if the teens had been sleeping when the killer arrived, probably entering through the back door, it would have been relatively easy to subdue all three.

In his oral report to the Arlington police department a few weeks after the crime, Wright told them the killer was a neighbor who probably had had some kind of “stressor” almost immediately before the crime: a divorce, a death in the family, the birth of a child, a fight with his wife or supervisor. He was intelligent, someone with a skill, but who had a difficult time holding a job. Possibly somewhat “macho,” he had to be fairly confident he could overpower three teenagers.

The killer’s background? The FBI profilers said he likely came from a household in which the maternal figure was dominant, the father a “non-entity” or rarely present. He probably had difficulty maintaining relationships with women and a history of not considering the consequences of his actions. And police should look for someone who appeared to be cooperative “up to a point,” Wright said. “[The killer] wants to be in a position to monitor how the investigation is going.”

A few things puzzled Wright about the crime scene. One was the almost toxic dose of cocaine found in John Bradley’s body. Could someone have killed Bradley because he stiffed them on a drug deal, or knew too much about someone else’s narcotics business? But Wright was convinced it was not a drug-related killing. “For these people, there’s a better and safer way to kill somebody,” Wright says. “[With this], there’s too high a risk of being seen. Bradley was killed, but there was more activity with the girls.”

Wright’s report coincided with the return of results on fingerprint matches. Investigators looked at their list of fifteen to twenty potential suspects, and one name popped out above all the others. One person whose fingerprints were in the house, who had been there the night before behaving in a bizarre manner, matched the profile: Ronald Trimboli.

•••

When the Arlington police began running criminal record checks on people close to the Lemieuxes, they unearthed some strange reports on the man who was quickly becoming one of their main suspects. One report had been filed in 1983 by Arlington police officer Ronald Bantz, who is now a detective.

Bantz was off duty one day when the manager of his apartment complex asked him to check into a problem at the apartment of Devon Trimboli, who reported seeing blood on the window and door and was concerned that her estranged husband was inside.

After grabbing his gun, Bantz walked through the apartment, noticing that there was blood on the windows, curtains, and walls. “I finally found Trimboli on the floor of a closet with clothes piled on top of him,” Bantz says. “He had a knife.” Bantz says Trimboli was extremely intoxicated and depressed. He was bleeding. Apparently he had cut himself breaking a window to get in. Bantz got the knife away, but says that when he told Trimboli they were going to the police station, he began to fight.

“He said that he wanted to die and I was going to kill him,” Bantz says. “He lunged for my gun, then dropped down from the second floor balcony,” gashing his head. Despite the injury, Trimboli continued fighting. “He kept saying he was a Vietnam vet and that his hands were deadly weapons. He scared the hell out of me.”

Another officer finally arrived and helped Bantu handcuff Trimboli, who was later charged with criminal trespassing. That wasn’t his only violent run-in with police; he was arrested in 1984 when police responding to an alarm caught him inside a Greek restaurant called the Red Snapper. He tussled with police before being arrested and charged with burglary.

Trimboli told police then that the owner had given him the key and asked him to burn the place so he could collect on the insurance. Trimboli was never tried because the owners returned to Greece, says Hugh Atwell, an Arlington police sergeant who later headed up the murder investigation.

Both reports on Trimboli indicated he was comfortable with knives. And the more police officers found out about him, the more he looked like the profile developed by the FBI, even down to the “precipitating event” that profilers believe can send a person lurching into criminality. A month before the murders. Trimboli’s wife, D.C., had a son. The boy had been sickly at birth and had come home only days before the murders.

Trimboli’s cooperation with police also fit the FBI schematic. In early July, he permitted police to search his home, where they discovered a shirt with several small spots of blood on the sleeve. They examined butcher knives in the kitchen, confiscating two. He permitted a search of his car, where nothing unusual was found. And Trimboli allowed police to take samples of blood and hair from his head and pubic region, in addition to fingerprints.

Trimboli also gave a voluntary statement to police. He admitted he was inside the Lemieux house the night before the murders at. 2 a.m. and 5 a.m. to make two phone calls. His newborn son was sick. Trimboli said, and his phone was out of order.

He said he went with D.C. to the baby’s doctor the next day at 8:30 or 9 a.m., and that his wife took his stepdaughter Hope swimming at 11 a.m. He also claimed that he had never been in the kitchen, utility room, or bedrooms of the Lemieux home.

Though he adamantly denied touching the laundry appliances in previous conversations, after being told his palm prints had been found on the refrigerator and the dryer, Trimboli added a paragraph to his statement saying that he might have taken a tour of the house several months before.

Trimboli denied killing the teenagers. But he refused to take a lie detector test, drawing his family in around him. Rocco went with him to police headquarters, insisting that there was no way his son was the person responsible. The investigation stalled, but the profile, fingerprint evidence, and discrepancies in Trimboli’s statements convinced police they had the right person. For one thing, Trimboli and his wife had not appeared at the doctor’s office with the baby until after 11 a.m., and the doctor maintained that the baby didn’t seem to be sick. Therefore, Trimboli had no alibi, except for his wife’s testimony, for the estimated time of the murder. And another tile was added to the mosaic police were assembling; a neighborhood woman told police she had seen Trimboli embracing Danielle in an “inappropriate”’ manner about two weeks before the murders.

However intriguing these details were, they did not add up to a smoking gun. Stymied, police turned to recommendations made by the FBI’s criminal analyst. After describing the murderer’s personality, Atwell says, Wright had also given them tips on ways to “ring his bell.”

Wright suggested they plant a story with a friendly police reporter, saying that results from a profile indicated the murderer was a neighbor who might have gone to the house without intent to kill. The story should suggest that the killer was undergoing a great deal of stress and may have discussed the murder with friends. They hoped to encourage Trimboli to confess, letting him know that they had narrowed their suspects to him, yet giving him an “out.” If he hadn’t meant to do it, the ploy subtly hinted, there might be leniency.

Then the police should begin a constant, overt surveillance of Ronald Trimboli- following him, interviewing his friends, and keeping up the stress on the suspect, in order to get him in a frame of mind to talk about the murders. Wright also warned police to be wary of a suicide attempt designed to gain sympathy.

The suggestions gave the police some definite steps to take, and they did so with a vengeance. For almost six months, unmarked police cars were omnipresent fixtures on Miguel Lane. “Wherever he went, we went,” Atwell says. “We were careful not to harass him. We never approached him.”

Still, it was obvious who the target was. Camill says her son laughed about the police presence, jumping into his car and racing nowhere to watch them follow him. But Atwell says their tactic seemed to have the desired effect. Trimboli would emerge from his house and shake a fist in their direction, Occasionally, Trimboli would sit in the police car and drink coffee with the officers. He had quit his job shortly after the murders; now, he virtually stopped going out at all. Meanwhile, the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office had begun grand jury proceedings on the case.

But things came to a head in October when police, believing that Trimboli was ready to crack, saw a female newspaper reporter enter his house. “We had worked him up to a point of anxiety,” Atwell says. Concerned that Trimboli might do her harm, they arrested him on an outstanding burglary charge in the Greek restaurant incident.

In hopes that Trimboli might confess, investigators brought in Gus Rose, chief deputy constable in Dallas County. A homicide detective for twenty-one years, Rose has a reputation as an interrogator who gets confessions. After Trimboli waived his right to an attorney, Rose began questioning him about his past.

“I gathered he had a great deal of emotional problems,” Rose says. Though fairly cooperative, Trimboli was on the verge of tears. “He kept saying, ’If they send me to the penitentiary on this thing I’ll kill myself.’ I had the distinct impression he was guilty, but I couldn’t really pin him down. I really felt like, given the opportunity to talk a little longer, he would have confessed.”

But after forty-five minutes, an attorney hired by Rocco Trimboli appeared and the interview was terminated. Trimboli was released in December, only to be arrested again ten days later at his parents’ home when the Tarrant County grand jury returned an indictment against him.

•••

On the wall beside Sharen Wilson’s desk hangs a testament to one of the biggest frustrations of the Tarrant County prosecutor’s career: a courtroom artist’s pastel drawing of Wilson addressing a jury. “The one there on the end was the one who caused all the trouble,” says Wilson, pointing. Eight days and more than halfway into the state’s case, Wilson’s first attempt to try Trimboli in February 1987 ended in a mistrial when it was learned that a juror had talked to relatives of the victims during a lunch recess. The second trial, six months later, ended in a hung jury. It was held in Cleburne because of extensive publicity in Tarrant and Dallas counties.

Wilson, who is now in private practice, was assigned the Trimboli case after being transferred into the court in which it was scheduled to be tried the first time. “When I got involved it had come perilously close to not being tried,” Wilson says. “There were some in the DA’s office who thought it was a dog.”

Determined to decide for herself, Wilson took home the enormous Lemieux file. “I went through it page by page to decide if I believed he did it.” Wilson says. “When I finished. I was convinced we had the right person.” The evidence was completely circumstantial, however; most murder cases are based on eyewitnesses or direct evidence, Wilson knew it would be one of the hardest cases she had ever tried.

The second trial began six months after the first, on a hot August day; it would last four weeks. Wilson began with a hard-hitting description of Trimboli as a man obsessed, a forty-year-old with an unnatural affection for a young girl, a yen that led to murder. Wilson relied heavily on fingerprint evidence, results of serology tests, and the testimony of Joanne Lemieux.

Joanne described how the families met, then testified that Ron Trimboli had never been to her house until the night before the murders. She told how he knocked on the back door at 2 a.m., asking to use the phone, though there was a public phone at a convenience store not far away.

“He was extremely nervous and he was sweating profusely around his face” Mrs. Lemieux testified. “The sweat was just pouring off of his face, and he was very agitated.”

She gave Trimboli a glass of water and he went into the living room, where he saw John Bradley sleeping on the sofa bed. Trimboli’s reaction to the boy was strange, Joanne Lemieux remembered. “He came in and raised his hands above his head and started saying ’What is he doing here? Why is he here?” I explained to him that he was there because he really had nowhere else to go, and that I had taken him in. And his response was, ’Well, who am I to judge?’”

She described how Trimboli returned at 5 a.m., again to call the baby’s doctor. Joanne went to work at 7:15 a.m. She testified that she called her children throughout the day, but she got no answer. At 10 p.m., after working a double shift at the medical answering service. Joanne returned home to discover her daughters dead.

Wilson worked hard to reveal the discrepancies in Trimboli’s story, putting on the stand the neighbor who testified to seeing Trimboli “embracing” Danielle and watching as the girl “squirmed away.” The prosecutor brought out the knives taken from Trimboli’s house. A substance identified as human blood had been scraped out from under the handle of one. A forensic serologist from the Fort Worth Police Department Crime Lab described semen taken from the bedspread as “consistent” with Trimboil’s blood group. Wilson brought out a shirt confiscated from Trimboli’s closet, the sleeves dotted with small drops of blood.

Wilson said that an amber glass covered with Trimboli’s prints was found on top of the dryer near John Bradley’s body. And with the help of a laundry room made of styrofoam boards, she presented her strongest evidence-describing to the jury how palm prints matching Trimboli’s were found on the top and front of the dryer, consistent with someone steadying himself as he leaned over to slash at a body on the floor.

But the defense team-Lee Joyner, Carl Mallory, and Mike Maloney-attacked the state’s case from all angles. Trimboli’s wife and stepchildren testified that he was with them most of the day. Sure, the shirt had blood on it-but where did it come from? Tests showed it could have been human or animal blood. And the knife? Though it tested positive for human blood, it couldn’t be traced to one of the victims. Perhaps Trimboli or his wife had cut themselves with it. As for the amber glass, of course it had Trimboli’s prints on it. He had asked for a drink of water while making his phone calls. John Bradley’s prints were on it as well. Perhaps the teenager put it on the dryer.

The traditional serology tests indicated that the enzyme group of 22 percent of the population of Arlington matched a semen stain on the bedspread. Though the defense couldn’t explain away the palm print on the dryer, they attacked the state’s fingerprint evidence by pointing out there were numerous fingerprints and palm prints all over the house that were never identified.

Trimboli’s lawyers went on the offensive, planting the idea that police botched the crime scene search and showing the police department’s own videotape to illustrate their point. It caught an officer standing on the dryer as he ran strings from blood spatters to the body of John Bradley-the dryer from which the damning palm prints were later lifted. And they criticized police for waiting eight hours before calling the medical examiner.

The attorneys cast suspicion on Mrs. Lemieux’s testimony, pointing out that detective Jim Ford’s report said he found her ’”unbelievable” when first questioning her. For example, she told Ford she found Danielle face up, arms above her head, and wearing jeans. They hinted that she was a religious zealot who left prophetic messages written on napkins lying about the house, yet invited a troubled youth to stay in her home with her two teenage daughters.

Stressing the level of cocaine found in John Bradley’s body and his reputation as a habitual user, the defense claimed that the crime had to be drug-related. Again, they pointed to the video of the crime scene. It showed an empty bottle of rubbing alcohol and an oven mitt on the floor of the kitchen. On a plate near the sink was a spoon containing a white residue. They asked if police had tested what appeared to be drug paraphernalia for the presence of cocaine or any other drug. There had been no such tests.

And what about Joanne Lemieux’s claim that she had seen two mysterious men in a dark pickup truck parked on the street when she left for work that morning? Had police ever found and questioned them? The answer, again, was no.

Producing two witnesses who testified they saw one of the girls late in the afternoon, the defense claimed that a band of drug-crazed maniacs had broken into the house and killed the teenagers, probably after 4 p.m., when Ron Trimboli was at work. The lawyers tried but were not allowed to introduce testimony about another shadow in John Bradley’s past: one of his roommates had been slain in what was believed to be a drug-related killing in Midlothian and Bradley had told friends he was afraid he would be next. They also were barred from giving jurors any information about the drug bust of one of Bradley’s associates. Nor did the jury learn that, during a search of the house in that bust, police found a hand-drawn map of the Miguel Lane area with the scrawled heading. “A Murder Mystery.” An “X” appeared to mark the location of the Lemieux home.

And the jury never heard Joanne Lemieux’s testimony that a friend of Danielle’s, a man in his early twenties, made a pass at her a few hours after taking her daughter to a movie. Describing the friend as “a professional hit man with a voracious sexual appetite who had used hallucinogenic drugs thousands of times,” Carl Mallory called the man a possible suspect in the murders.

In the end, after days of deliberations, each side convinced six jurors they were right. Several of the jurors told attorneys later they weren’t convinced one person could subdue three teenagers. “It was tough to take,” says Wilson, the frustration in her voice evident two years later. “But you don’t dismiss it because of a six-six.” Plans were being made to retry Trimboli when prosecutors heard the defense had filed a motion to take their client’s “genetic fingerprint.”

•••

The first time a “genetic finger-print” was used in a criminal case was in England in 1987, when more than a thousand men in a clump of small villages were screened to track down a rapist/murderer. The technique had been developed by a British geneticist who discovered that some portions of each person’s DNA, the double-helix molecule coiled in the nucleus of most living cells, were highly variable. By taking DNA from blood or other bodily tissues and “chopping” it up using special enzymes, those places-restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP)-could be mapped, then compared to the results from the same test run on forensic evidence.Some experts look forward to the day when DNA printing is done routinely, despite the screams from civil libertarians.

In the United States, results from a DNA print were first admitted in court in a 1987 murder case, Oklahoma v. B.J. Hunt. After a mistrial, the accused rapist was found guilty. The U.S. firm that performed the test was Lifecodes Corporation.

Both the defense and prosecution attorneys in the Trimboli case had heard about the DNA test but were unsure whether enough evidence existed to perform the RFLP test. The defense attorneys put the question to Trimboli. This test could prove his innocence. Did he want to take it?

Jailed two years and lacing a third trial, Trimboli decided he wanted the test. After filing a motion asking the court to have the test done, defense attorneys announced the move to the press. “If it comes back positive, it nails our man,” defense attorney Mike Maloney told a newspaper reporter.

Unknown to the defense, prosecutor Gill had been investigating another technique that could use smaller quantities of evidence. After the judge ruled that the DA’s office should have the test done, prosecutors sent samples of Ronald Trimboli’s blood as well as semen-stained swatches from the bedspread and a vaginal swab taken from Danielle’s body to a California scientist named Ed Blake, whose PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technique uses smaller quan-tities of DNA, but is less informative than the RFLP process.

The results came back: Trimboli’s DNA “DQ Alpha” matched the bedspread semen stain, as did 3 percent of the Caucasian population. Not bad odds, but Gill and Alan Levy, the “hot shot” prosecutor brought in to handle the case after Wilson went into private practice, thought they might get even better numbers. They asked Blake if there was enough material to run an RFLP test; Blake said he thought so. Everything was sent off again, this time to Valhalla, New York, home of Lifecodes Corporation.

The Lifecodes report came back, and in Maloney’s words, it nailed their man. The DNA from Trimboli and the DNA from the bedspread matched. The odds of a random match, the Lifecodes report said, were 54.9 billion to one.

Mallory, Maloney, and Joyner were stunned. Joyner says they met in the bar at the Worthington Hotel. “We sat back and looked at each other and said. ’Shit, what do we do now?’” Joyner says. “I said, ’He’s lying to us. Hell, he did it.’”

Maloney told a newspaper reporter that the test hadn’t shaken his faith in Trimboli’s innocence. “It’s inconceivable to me that somebody who did this [killed three people] would want that test to be done,” Maloney said. Mallory later left the case and did not return D’s phone calls. Joyner stayed on, and the court appointed Bill Lane to handle the DNA portion of Trimboli’s defense.

Lane was a DNA expert by virtue of the fact that he had represented Barry Dean Kelly, whose trial, only a few months before, was the first to use DNA in Tarrant County. Accused of the rape and murder of his girl-friend’s mother. Kelly was seen in the mother’s truck and had sold her jewelry. His DNA matched DNA taken from a semen stain on the mother’s bedspread. Suspecting that he would be appointed to represent Trimboli, Lane says he knew when he was assigned to the Kelly case that it was meant to be preparation for the most sensational case Arlington had ever had. Both Levy and Lane knew that what happened in the Trimboli case could affect the way DNA evidence was handled in Tarrant and Dallas counties in the future.

Lane didn’t like the odds, but as he and Joyner began looking closely at Lifecodes and its techniques, Lane says he became convinced that-based on Lifecodes’ own published criteria-the DNA “fingerprint” did not nail Trimboli, but cleared him.

The third trial, also held in Cleburne, got under way in March 1989. It wasn’t simply a rehash of the other two trials with DNA added. The stale abandoned the knives and the blood-stained shirt. Instead of relying on styrofoam replicas, they went to the shop where Joanne Lemieux had purchased her appliances and borrowed a washer and dryer to use in their exhibits.

The defense managed to inform the jury that three pubic hairs were found on Danielle’s buttocks; two were consistent with Danielle, and the other was not consistent with Trimboli. Lane also introduced testimony by Trimboli’s stepdaughter that he had worked on the dryer several weeks before the murders at the girls’ request; it was the first time in four years that Trimboli had offered an explanation for the prints.

But the heart of the case was DNA. The judge had given the defense a blank check to visit the Lifecodes laboratory in New York and to bring in experts from all over the country. The DA’s office also mounted an expensive prosecution, bringing in a Houston geneticist named Thomas Caskey from a conference in Italy. The prosecution had at its table biologist Benjamin, who did not testify but listened to testimony and assisted.

After a hearing that established that the technique was scientifically reliable and accepted, a battle of scientists ensued. Lane attacked Lifecodes for issuing a report that simply declared a match without giving any of the underlying data concerning the molecular weights of the fragments or the autora-diograms, photographs of the DNA much like X-rays. He forced Lifecodes scientist Kevin McElfresh to admit that they evaluated the autorads visually, not by measuring the molecular weight of the fragments and comparing them “within three standard deviations” as the company’s literature claimed, and raised a cloud over the issue of “band-shifting- a phenomenon seen when bands don’t exactly line up, but are still declared a match.

Levy countered Lane’s arguments with his own experts and struggled to deflect what he thought was the most damaging aspect of the report: the high numbers. They wanted to present the most conservative figures in order to deflect any defense attack.

At the beginning of the trial, Trimboli seemed relaxed, greeting one of the prosecutors amiably and chatting about horoscopes and Italian cooking with those around him. But as the trial edged into its third and fourth week, he became increasingly agitated and nervous. His parents sat in the courtroom almost every day. talking to reporters and spectators who came to watch the hottest show in Cleburne.

One of the most dramatic moments in the trial came when Gill presented defense expert Dr. Karl Muench with a copy of Lifecodes’ molecular weight data in a Florida case. Muench, a professor of medicine at the University of Miami School of Medicine, had called the print in that case a match, but admitted under questioning by Lane that he had never seen the underlying numbers. Using his pocket calculator, Muench ran a series of standard deviations, then declared that to his surprise, by a strict application of Lifecodes’ criteria, the bands did not match.

During a recess, in an attempt to prove that Muench was lying, Levy phoned the Florida prosecutor, who admitted that he had never seen the underlying data either.

The final count was nine experts for the match, five experts against it. It was the first time since DNA was introduced as a forensic tool that the test, at least as performed by Lifecodes, had faced a significant challenge. Even the prosecutors professed grudging admiration. “It was a damned good defense,” Gill says.

But despite the defense’s strong attack, jurors look only seven hours to convict Ronald Trimboli of three counts of murder. The foreman, Gene Roy of Burleson, told a newspaper the DNA evidence was not the overriding factor in the panel’s decision. Another admitted the DNA testimony was confusing, but said that the scientists did a good job of explaining it. “It’s the coming thing,” Fred Matson of Alvarado told a reporter. “It’s a proven theory that this thing will work.”

But nationwide, several months after the Trimboli case, controversy erupted over the “infallible” DNA testing and its use in criminal cases, with experts on different sides of the issue sniping diplomatically at each other in scientific journals.

The controversy boiled over during the summer of 1989 in New York v. Joseph Castro, a case tried in the Bronx in which scientists held an impromptu scientific conclave during a pretrial hearing on the reliability of the test. After their report severely criticized Lifecodes methodology and interpretations, the judge threw out the DNA evidence.

“This case makes the Castro case look good,” says Dr. Moses Schanfield, laboratory director for Analytical Genetic Testing Center in Denver, who testified for the defense in the Trimboli trial. “The DNA evidence in that case was better. But until Trimboli, nobody working on either side of a Lifecodes case had actually looked at the autorads and the data behind them. This was a bad circumstantial case, and the DNA evidence was basically non-informative. The fact is if that were done in my laboratory, the results would never have been reported out.”

Karl Muench agrees. “When I applied Lifecodes’ published methodology in the Trimboli case, there was not a match. The Trimboli case didn”t get national press, but it was very parallel. And those problems are not confined to the Trimboli and Castro cases.”

Across the country, prosecutors and defense attorneys are scrambling to make sense of the clash between science and the law over DNA evidence, lining up experts who support their side to testify in court. Currently, there are at least two scientific committees examining standards for DNA testing in the laboratory and interpretation of results. The FBI has developed criteria that DNA forensic labs nationwide will follow. And, over the next few years, DNA will be on trial as appellate courts hear the appeals of dozens of those convicted of murder and rape on the basis of DNA tests.

“Lifecodes says they have had ninety convictions, but in the vast majority, nobody ever saw the DNA evidence,” Schanfield says. “They just provide a report. In this situation, the evidence was off in some cases by almost seven standard deviations, instead of the three standard deviations published by Litecodes. That’s like betting on horse races. You have to have an objective criteria for defining a match.”

Schanfield predicts that there will be a DNA shakeout in the coming years. The FBI began doing it last year. Many major metropolitan police departments are opening their own labs. Dallas County will have a DNA lab this year, and will follow the FBI’s techniques, according to Dr. Irving Stone. Stone, now chief of the physical evidence section of the Dallas County Institute of Forensic Sciences, will head the Dallas County DNA lab. As numerous other techniques proliferate, some experts stress the value of a standard technology, especially if the dream of a national computer bank of DNA prints of known criminals is to be realized.

Benjamin, who sat at the prosecution table during the Trimboli trial, says he is convinced that the DNA print matches Trimboli to the bedspread found beneath Danielle Lemieux. “But I don’t know if you should convict on DNA alone,” he says. “There’s always the possibility of procedural error.”

He looks forward to the day when DNA printing is done routinely, despite the sure-to-be-heard screams from civil libertarians. “If the military did it, there would be no more unknown soldiers,’” says Benjamin. “If we typed everybody at birth, it might impact child kidnappings. You could immediately tell if you have a serial rapist or murderer, or if it’s a copycat. We need to get victims to understand that if they can get it done quickly, they can nail the guy to the wall.”

•••

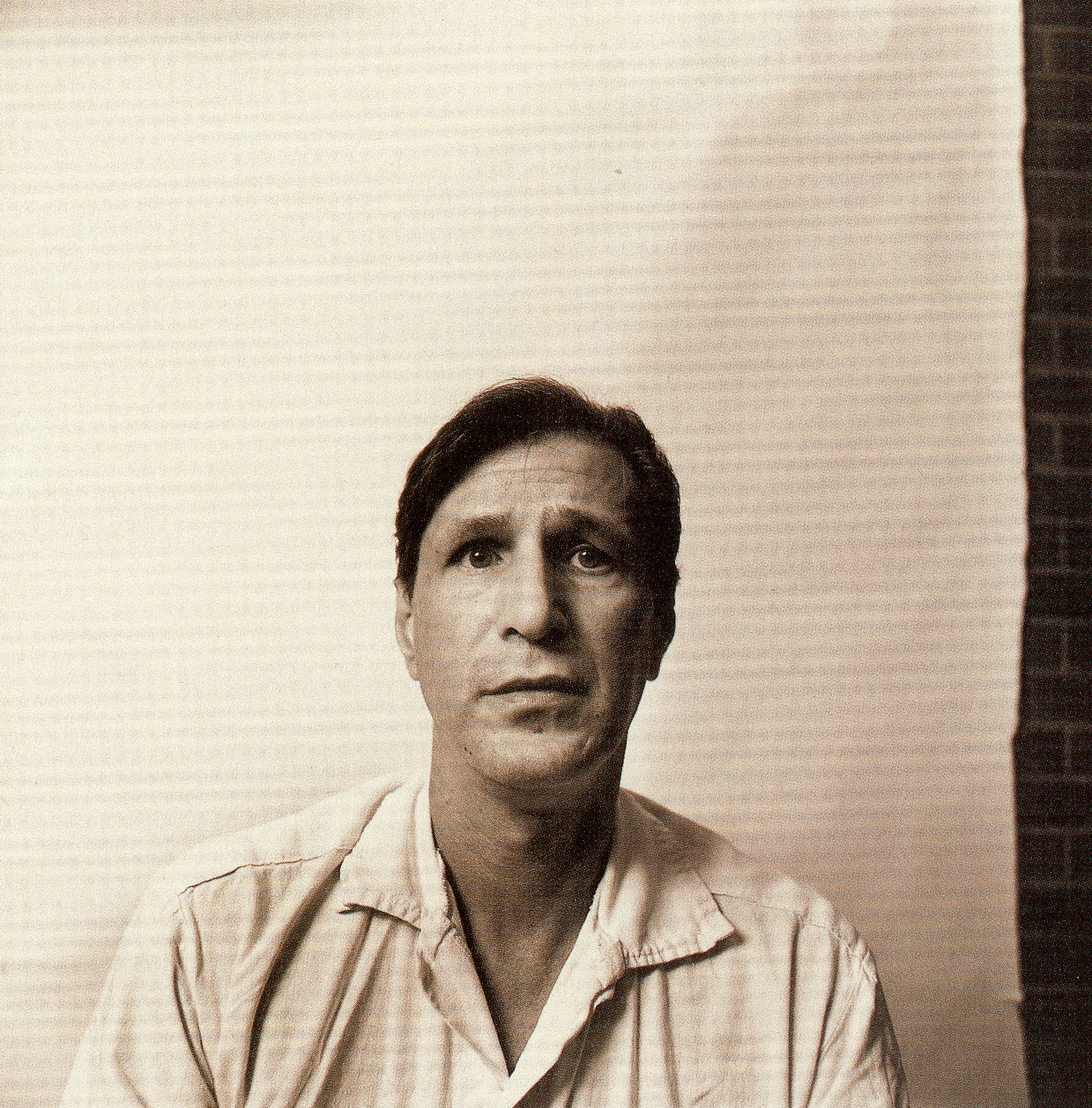

Dressed in prison whites and sneakers, Ron Trimboli saunters into the small institutional office in the heart of Ellis Unit I near Huntsville with a brown file of DNA articles under his arm. Adamant that he will not be photographed or interviewed in a “cage,” Trimboli has arranged with the warden to use a private office to talk. A guard sits outside the closed door.

He’ll be forty-five in a month or so, but his black hair is not yet touched with gray. Hollows surround the dark eyes, which in early photographs gave him the look of a suave crooner. On his left wrist stalks the tattoo of a black panther. He fought a battle with prison food early on, but has taken off most of the paunch. For years Trimboli prepared lobster and veal parmesan; now he cooks chicken and pork, day after day, in the prison kitchen. The recipes leave much to be desired.

If he’s adapted to the cooking, he hasn’t adapted to other aspects of prison life. “You’re always on guard,” he says. “You’re always looking behind you.”

Given an opportunity to talk about the investigation, the trials, and DNA, Trimboli is glib, charming, likable. In his presence, it’s easy to believe this has all been a tragic mistake, that events conspired to pick him out of the pack, prosecute him, and put him away for life. But what would a triple-murderer look like, talk like?

His explanation of what has happened to him is simple: he believed in his innocence. He thinks back, laughs a little, “I have a big mouth,” he says. ’”When you have nothing to fear…that was my problem. I didn’t take it seriously.” He says he even teased the police who were following him a little. “One said. ’You lead a boring life,’” Trimboli says. “Hey, what do you want me to do, rob a jewelry store?”

He spends his days thinking about his upcoming appeal, and making a jewelry box for his mother out of match sticks. A handkerchief he decorated for her, with a poem about a mother’s love, is framed and hung at his parents’ home.

The DNA testimony at his third trial left him confused, he admits. “I know H-2-0 is water and H-2-0-H is hot water,” Trimboli says. “If more emphasis was placed on the facts, they would have found out I couldn’t have done it. You lose a lot of respect for the system. They can build a case on you and get you convicted.”

He agreed to the DNA test because he was innocent, Trimboli says. “I let them search my house, my car. Would a guilty person do that?” he asks.

He looks forward to the day when his appeal is heard, confident that his conviction will be reversed. “But I don’t want to just walk away,” he insists. “I want a new trial. I want to prove my innocence. There are too many things that aren”t right. My theory is they fell victim to something John Bradley was involved in. One day he’s in the house, the next day they’re dead.”

He picks up his file, shakes hands, and walks away. The incredulous look on his face seems to linger long after he walks outside the office and is swept up in a stream of other inmates walking to dinner.

Despite Trimboli’s claims of innocence, despite the steadfast belief of his attorneys-long inured to protestations of guilty clients-that Trimboli didn’t kill three teenagers one hot summer night in 1985, despite the quarrels over DNA, misgivings remain. What about the discrepancies, the convenient “memory loss”’ that resulted in his forgetting that he worked on the Lemieux’s dryer until the third trial? Everything, it seems, can be explained away. The incident with his ex-wife “got blown out of proportion,” he says, as did the situation in the Greek restaurant. He simply arrived after it had been vandalized, and the cops showed up before he had a chance to call police.

And what about the PCR DNA test? Never disputed, it put him in the 3 percent of the population that could have committed the murder. What are the odds that a man who had nothing to do with the murder, but had left a palm print above a dead body and a trail of lies about his actions, would be within that 3 percent?

Even as Trimboli touts his innocence, as attorneys ready his appeal, relatives and friends of the murdered children go on with their lives, wondering what might have been. And careful readers of the literature being amassed over the DNA controversy might notice a peculiar incident, now little more than an addendum, that illustrates one problem with relying on scientific experts using this new technology to decide guilt and innocence, life and death.

In the pretrial hearing in New York’s Castro case, Lifecodes claimed that blood found on the watch of a man accused of killing a woman and her two-year-old daughter was the mother’s blood. The dissenting DNA expert adamantly claimed the test proved it was not, again based on Lifecodes” own criteria. The judge threw out the DNA evidence. But the prosecutors trying Castro had other strong evidence linking him to the crime. He pleaded guilty to the murders.

The judge, determining the man’s sentence, asked Castro point-blank, demanding that he be truthful: did the blood on the watch come from his victim? After all the shouting over molecular weights and band shifts, contamination of forensic specimens and laboratory procedures, the judge wanted to know who was right. Was the DNA print a match?

The answer came back, simple and unscientific, from the one man who knew for sure: “Yes.”