It is a drama for you tragedians, you lovers of Oedipus, you friends of Lear and Iago. It is staged for you who appreciate the good intentions that pave the walls of Hell and for you who savor the fatal flaws that inevitably bring heroes and villains down. Lend an ear to a classical tragedy worthy of Aeschylus but writ and played in Dallas. Be silent that you may hear of the Dallas Citizens Charter Review, how it started like a guilty thing upon a fearful summons and how it met its final fall to reprobation.

It is not a pretty drama, but tragedy seldom is. It begins with a mayor, Annette Strauss, who dares to dream of greatness but who possesses neither the determination nor the strength to wring reality from her vision. It ends with despair and suffering and open threats of rioting in the streets. It is about class and race and the evil that men do. Its theme is found in a line uttered by one of the principal characters, Al Lipscomb, a line that, perhaps, describes all great tragedy.

“God-ziggety! We came so close. Go-oo-oo-odd-ziggety!”

Indeed, the Dallas Citizens Charter Review Committee, appointed by Strauss and company to restructure the City Council so as to include minorities, came very near its goal. I( edged to within a hair of devising a new plan of government that might have appeased all but the most recalcitrant among those who object to what now is. It sidled ever so close to fulFilling the dream the mayor voiced when she set the review process in motion early in 1988, a dream of uniting a diverse and contentious population, of bringing the city of Dallas together.

But close doesn’t count, except in Kierkegaard. The final result, the package of charter amendments overwhelmingly approved by city voters August 12, was a hollow failure despite its victory at the polls. Its controversial 10-4-1 plan-ten council members representing tight, local districts, four elected from regional districts each including a quarter of Dallas residents, and a mayor chosen by the city as a whole-satisfied no one.

Since council resolved to present 10-4-1 to voters, residents have witnessed the first organized civil rights protests in recent history. Worse, they have seen African-Americans set against each other to hurl epithets like “Uncle Tom,” “Oreo,” and “Coconut.” They have heard nasty allegations of conspiracy within the Dallas establishment on the one side, and among militant minority groups on the other.

And the voters may see, ultimately, that their ballots counted for little or nothing. The U.S. Justice Department and federal courts, either here or in Washington, D.C., may impose upon the city a system of government that has little to do with the voters’ will expressed in the election. Dallas is confronted with a new round of demands that it open its political process to all citizens. No sop to equality, in the form of a so-called voluntary charter change, can stay the press of those demands. But the most devastating effect of the recent charter review process, the one likely to linger longest and most dangerously, is the effect on the internal fabric of the city.

Instead of a Dallas brought together, the city stands today more divided along social, ethnic, and economic lines than, perhaps, ever before in its history. Right now, some believe, the city is a volcano waiting to erupt.

“I think we will have the National Guard marching in the streets of Dallas before this time next year,” says Lipscomb. “I think racial violence in Dallas is a sure thing before very long.”

Mexican-American activist Domingo Garcia agrees: “I don’t condone violence, but I wouldn’t be surprised to see some people take the situation into their own hands. Our people have been angry for a long time, and this 10-4-1 proposal has only made it worse.”

Such dire predictions may well be the kind of hyperbole racial issues have inspired before in Dallas. There is little doubt, though, that 10-4-1 resulted, as Dallas Morning News reporter Catalina Camia put it, in “the most racially divisive election in Dallas history,” For that reason, if no other, the charter review process may only be counted a disaster. Reform of the local governmental structure was wrought by Strauss and a host of other city leaders as part of a grand plan to relieve racial tensions here. It certainly was not intended to exacerbate them.

The process began early in 1988 after a series of police shootings galvanized the city. The death of officer John Glenn Chase, especially, had tightened the strings of racial tension. Reports that a crowd had urged a deranged black man to murder the white officer outraged every part of the community. Then-police chief Billy Prince injected race into the incident with a charge that Lipscomb and black councilwoman Diane Ragsdale had created a climate of hostility that fostered such brutality.

Former Dallas Cowboy Pettis Norman, now a Dallas businessman, foresaw racial strife and possible violence unless something was done to soothe feelings and relieve animosity. Through an aide to Annette Strauss, Norman urged the mayor to form a task force charged with addressing the situation head on.

“At first, the mayor told me she didn’t want to do it. She didn’t think it was a good idea,” Norman recalls. “But then, in a few days, she called me back and said she had changed her mind. She agreed that the races needed to sit down together and try to come to some kind of understanding.”

The forum Strauss created for bringing Dallas’s diverse groups to the same table was a task force she called Dallas Together. Its members included seventy-nine persons representing virtually every ethnic group, civic organization, and educational background found within the city. Headed by insurance executive Tom Dunning, the group held a series of intense meetings that sometimes resembled encounter sessions studying education, economic opportunity, business development, the underclass, and political participation in Dallas.

In January 1989, Dallas Together released a no-holds-barred report recommending sweeping reforms designed to encourage equality of opportunity. Among the report’s recommendations was a call for a committee to restructure city government in ways that would open doors for minority service, especially on the City Council.

Strauss seized the proposal for city charter review and reform as her own personal issue. Facing an election that promised to be rancorous-if not very challenging-she saw charter review both as an attractive political issue and as a way to leave her mark indelibly upon the face of the city she governed.

At Strauss’s urging, the City Council in March created the Dallas Citizens Charter Review Committee, a panel of fourteen voting members and eleven alternates, to draft a new constitution by which Dallas would be governed. Strauss named attorney Ray Hutchison, who had drafted the Dallas Together report calling for charter review, chairman of the committee. Norman and Joe May, a Mexican-American who manages the U.S. Small Business Administration’s equal employment opportunity program in a five-state region, were elected vice-chairmen.

Remaining voting members included Lipscomb, Ragsdale, and then-councilman Jerry Rucker along with former Mayor Jack Evans and former councilmen Dean Vander-bilt, Don Hicks, and Lee Simpson. Others were: Dr. Phap Dam, director of world languages for the Dallas Independent School District; Oak Cliff businesswoman Dr. Yolanda Garcia; City Plan Commission member Joyce Lockley; and businessman Herschel Brown. It may only have been coincidence that all three women appointed to the committee-Garcia, Lockley, and Ragsdale-served double duty as ethnic minorities.

In addition to voting members, the City Council appointed eleven alternates. The whole group was instructed to examine the structure of the City Council and the existing system of eight single-member and three at-large districts, as well as the powers of the mayor and city manager, council pay, and campaign spending.

From the first meeting it was clear that election districts would occupy the bulk of the committee’s attention. The stage was set for a tragedy in three acts.

ONLY ABOUT TWENTY-FIVE MEN AND women, nearly all of them white, dotted the auditorium at Walnut Hill Elementary School May 17. Because of a bureaucratic snafu, word of charter review committee public hearings had not leaked to the public. As a result, committee members and alternates nearly outnumbered the audience at the first of eight forums.

For the Dallas Citizens Charter Review Committee, it was the opening curtain, and the show began badly. Already the group had heard from experts and drafted a questionnaire soliciting ideas from some ninety civic, racial, and political organizations. But the Walnut Hill meeting was the first real public exposure, and it left a bad taste in a lot of voters’ mouths.

That the public notice had not been properly posted was no fault of the committee’s. But northwest Dallas residents read into it an attempt to limit the debate. Certainly, residents of that area possessed strong opinions. Among the eight who spoke that night, several urged a living wage for elected officials. Some called for a stronger mayor. Two recommended more single-member districts, while one suggested replacing the current at-large council seats with representatives elected from quadrants of the city.

Before the remaining seven meetings, crammed into a two-week schedule with two hearings on one particularly hectic Saturday, Hutchison saw to it that notice was widely published. Huge, sometimes boisterous crowds shouldered into sessions, which usually began at 7 p.m. and dragged on until nearly midnight.

Several North Dallas citizens’ groups objected to single-member districts and demanded a return to the system of the Seventies, when all council persons were elected at large. Oak Lawn homeowners proposed combinations of single-member and at-large districts and recommended giving each resident a handful of votes to spread among council races or to cast all for one favorite candidate. At the Martin Luther King Community Center in Diane Rags-dale’s district, speakers without exception objected to having any members elected at-large, including the mayor.

And Pettis Norman hatched an idea that later would be crucial: “Suppose we have mostly single-member districts but we add two super districts, one for South Dallas and one for North Dallas. Suppose we can prove that it would be fair to everybody.” He became the first committee member to publicly suggest a combination of single-member and super districts.

Hutchison did most of the talking for the committee, and his soliloquies often resembled filibusters. He opened each session with a rambling lecture about how important charter revision would be. Often, he promised that a straw poll at the end of the session would tally audience opinion. When the end arrived, though, committee members barely remained awake and the crowd had dwindled to a handful. Instead of taking a poll, Hutchison closed with a monologue.

“I wish that man would learn how to shut up and get on with business,” former Mayor Jack Evans remarked to Joe May as they rode an elevator together after one particularly arduous session. “I’ve never met anybody who’s so much in love with the sound of his own voice.”

Though most speakers represented organizations that returned questionnaires, miles of videotape shot by a public access channel form the only complete record of those hours of public meetings. No written chronicle exists. And because Hutchison rarely conducted his straw poll, the weight of opinion was not measured.

“There wasn’t any attempt to really find out what the majority of people were thinking and then reflect those thoughts in the charter amendments,” Domingo Garcia complains. “Hutchison was just going through the motions in those hearings. He wasn’t really interested in what the rest of us had to say.”

Not so, says Hutchison. It was because of those hearings that he abandoned what he called “a preconceived idea that we needed some at-large council districts.” Hutchison says that opinions expressed by speakers and returned in the questionnaires led him to the idea of four so-called “super districts.”

Early discussions among the committee were civil, even friendly. But it was clear from the beginning that Hutchison favored the 10-4-1 plan and meant to steer the committee toward it. In his own mind, Hutchison says, he had weighed all options-everything from a council elected entirely at large to as many as a hundred single-member districts-and he was sure that 10-4-1 was best for the city. That rather arrogant decision, he now concedes, may have been a mistake.

“1 was told by a very important friend on the committee that you need to let people win a few battles and lose a few so they could meet in the middle,” he says. “If I had done that, we might have come out with the same recommendations, but some members of the committee might have felt more a part of the process.”

If Hutchison knew before the first gavel sounded that 10-4-1 would be the plan, so did everyone else. “There was never any question about any other plan,” says Phap Dam, a strong supporter of the eventual committee recommendations. “We were talking about 10-4-1 from the start. I don’t remember that anything else was considered.”

Grumbling about a “hidden agenda,” Lipscomb and Ragsdale considered walking out. Their constituents rejected at-large representatives, and city quadrants looked like at-large districts to them. “If it looks like a duck and it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, it’s a duck,” Lipscomb chanted again and again. Even Hutchison occasionally referred to 10-4-1 as “ten districts and four ducks.”

To head off a defection, Pettis Norman called a minority caucus at the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce. Present were Domingo Garcia, school board members Yvonne Ewell and Kathlyn Gilliam, and all the committee’s black and Hispanic members.

Exactly what took place during that caucus is not clear. Most who were present say the group unanimously backed a 12-1 council-twelve single-member districts and a mayor elected at large. For Garcia, who favored 16-1, for Lipscomb and Ragsdale, who opposed electing even the mayor at large, and for Joe May, who advocated 10-1, the 12-1 plan represented a compromise, but one they could live with.

Others say Norman agreed to give up his two-super-district proposal and join the 12-1 faction. But Norman recalls the agreement differently. So many population numbers were batted around, he says, that he was thoroughly bewildered. “I was confused about the numbers. I didn’t feel I knew enough to support any proposal.”

Before a session the next day, Memorial Day. Hutchison got wind of the caucus’s 12-1 plan. He was furious. Committee factions had no business meeting in secret, he said. He concluded that blacks and Hispanics would not compromise because they believed they could get whatever they wanted in court. Minorities were holding the city hostage to the lawsuit, he ranted.

Sensing an impasse, Norman sought a recess of eight to ten days. He argued that an outside expert, one who could look at city population figures and draw districting options, should be recruited. He even had one lined up, a political think tank from Washington. D.C. But Hutchison declared, in so many words, that the committee could vote on 10-4-1, or it wouldn’t vote on anything. He moved to adjourn indefinitely.

“I asked him not to do that,” says Norman. “I felt we could compromise if we just took a few days to look at some objective numbers and let people cool off. But he had his way and that’s what he was going to do.”

Hearing Hutchison’s motion. Joe May realized that the entire charter review process was in jeopardy. He rushed around the table for a hasty conference with Lipscomb and Ragsdale.

“We can’t let this just fall apart,” May whispered. “How about 12-2-1? Could you live with 12-2-1?”

“I can’t support it, but I won’t oppose you on it,” Ragsdale replied.

Lipscomb answered, “I can go with that. Let’s go with that.”

Compromise was in the air, but when May tried to introduce his new plan, Hutchison shushed him and called the role on a vote to disband.

As Act I ended, the committee and the charter review were in shambles. The seeds of conflict were well and firmly planted.

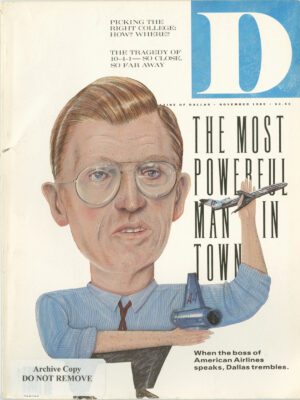

ROBERT CULLUM, FRANK HOKE, George Underwood, J. Lee Johnson, Bayard Friedman, Babe Fuqua. The fierce pantheon of old Dallas summoned the young lawyer to an office in Oak Cliff that day in 1966. Sternly, soberly, they outlined a plan to end the Dallas/Fort Worth airport wars by constructing a splendid new facility halfway between the two cities. They needed a clever, dedicated attorney to manage a raft of financial intricacies. The fellow before them, they judged, was the man for the job.

The bright-eyed attorney was Ray Hutchison, thirty-five years old. just seven years out of law school, newly converted to public finance law from corporate practice, which he eschewed because it meant too much time away from Dallas. Hutchison gladly accepted the assignment, of course. From that moment, he was on his way to becoming a wealthy man. And he was securely situated inside the Dallas establishment.

For a young man who had grown up in South Dallas near Second and Hatcher, one of the city’s poorer neighborhoods even before World War II, working on a project of such scope and vision might have been a crowning achievement. Certainly, it was more than Ray Hutchison dreamed of when he rode the trolley to Crozier Tech High School in hopes of becoming an auto mechanic, It even was more than he had hoped for when he entered Southern Methodist University on the GI bill, defying a registrar who believed he would stumble in the halls of academe.

But for Hutchison, the airport project was a first step, not a fulfillment. Because of his close ties to men like J. Erik Jonsson and because of what some associates describe as a stunning legal mind, he had a hand in almost every major Dallas milestone from the early Sixties onward. A financing scheme for the development of Texas Stadium was Hutchison’s brainchild. He helped engineer a deal to move the American League Senators out of Washington, D.C., and resurrect them in Arlington as the Texas Rangers. He developed bond packages for Dallas, Irving, and other cities, and he advised the Dallas Area Rapid Transit Authority from its beginning.

In 1972 and again in 1974, Hutchison was elected to the state legislature, one of the first Republicans ever to serve Dallas County. In 1978, he was a favorite to become the state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction. At the last minute, though, Bill Clements sneaked out of the oil field and wrested the distinction away.

Hutchison was unquestionably qualified for the task of chairing the Citizens Charter Review Committee. And with his ties to the establishment, it was clear that he could serve invaluably as a salesman for any plan that might go against the old Dallas grain. Even Al Lipscomb initially supported Hutchison as the man for the job.

But in examining Hutchison’s credentials, Lipscomb and others overlooked the seductive flavor of power. Hutchison has sampled power often, and he likes the taste of it in his mouth. Apparently, it is a thirst approaching addiction.

Picking up his marbles and going home-that is, disbanding the committee rather than tolerating unwanted proposals-almost certainly was a power play. By precipitating a crisis, Hutchison knew he could consolidate his position.

In the two weeks following the Memorial Day meeting, Hutchison played power with some of the best in the game. The channels were not always direct. Former Mayor Evans and former council members Hicks, Vander-bilt, and Rucker reportedly were among those who helped carry his water. One way or another, though, Hutchison reached out to every power holder and power broker in this city. In nearly all cases, they urged him to call the committee back into session, and he agreed to do so provided they promised to support the 10-4-1 plan when it finally emerged from the debate.

Mayor Strauss, who claims she did not know of Hutchison’s strong Republican Par-ty ties when she appointed him, apparently went one step further. Charter Review, her baby from the beginning, was so important that she would have promised him anything if it could get the process moving again. Instead, she assured her chairman that anything the committee presented in the way of recommended charter amendments would go directly to voters, unchanged by so much as a comma.

In effect, Hutchison’s ploy had won him the right to rewrite the city’s constitution in any way he chose. All he had to do was influence a majority of the fourteen voting members of the committee and he could design a city government run by a queen and a prime minister, if that’s what he wanted. And winning a majority of the committee, it seemed clear, would be no heavy problem.

When Hutchison called the committee back into session after a two-week hiatus, the civility that had characterized the earlier sessions was gone. Hutchison knew he had the upper hand, and he was willing to exercise it. He ignored dissent, belittled those who disagreed, and rammed through proposed charter amendment language, sometimes without even bothering to explain it.

He treated Ragsdale, Lipscomb, and May with disdain and condescension. At one point he lectured Ragsdale, “If you want to interrupt the chair, you have to say, ’I rise to a point of personal privilege.” Those are the words you say. ’I rise to a point of personal privilege.’ ” You could have cut his sneer with a chainsaw.

Toward the end of the deliberations, Hutchison actually laughed aloud when Joe May proposed a charter change not to his liking. “You know we aren’t going to pass that,” Hutchison chuckled. “Do you have a serious amendment?”

In his own defense, Hutchison says, “These issues tend to activate a diversity of opinions and, in some instances, passions. You sometimes wear your feelings on your sleeve when you sit in such an intense legislative environment for four months.”

Hutchison was not the only committee member who dropped the mask of friendly dialogue. Ragsdale and Lipscomb and occasionally Jerry Rucker also opened fire on those who disagreed with them. More than once, Norman was openly called an Uncle Tom, an epithet that stung him deeply.

Lipscomb alienated an entire minority community when he mentioned his own service in World War II and suggested that Asians did not have the courage to stand and fight Communism in their own countries. Dr. Phap Dam, who suffered months of loneliness and severe depression after his native Vietnam collapsed and he was forced to flee in 1975, was particularly offended.

With hostilities more or less out in the open, tensions in the room during the final, crucial sessions of the Dallas Citizens Charter Review Committee were almost palpable. May, Lipscomb, Ragsdale, Lockley, and their alternates were in one camp. Everyone else was in the other. Only minority advocate John Fullinwider, Ragsdale’s alternate, and former councilman Lee Simpson seemed willing to shout across the chasm.

On only one major issue did the minority faction prevail. That issue had to do with the appointment of city boards and commissions. Ragsdale and Lipscomb insisted that the mayor and each council member should appoint one-and only one-delegate to these important bodies. Their intent was to eliminate the current appointment system in which some members may make several appointments while others make none. They sought parity on each advisory body.

Lipscomb and Ragsdale carried the issue. But in perhaps the most Machiavellian maneuver of the charter review process, Hutchison eventually subverted their intent.

In the last meeting of the committee, after Hutchison already had briefed the City Council on the group’s findings and proposed charter amendments, the chairman handed out a finished document for ratification. For the first time, committee members saw the effect of their deliberations collected and written down. Their task was to wade through a thin ream of legalese and affirm the proposals.

Buried in the final document was a paragraph concerning the appointment of boards and commissions. Its wording directed that each council member should appoint one person to each advisory group. But it left open the possibility that some council members could make one appointment while others selected six members or a dozen.

Neither Lipscomb nor Ragsdale attended that final meeting. If they had, perhaps they could have fought for their point and won. As it was, only Joe May spoke up to challenge the final wording.

“I never intended that we would reduce the size of any board or make every board an exact multiple of fifteen [the size of the proposed 10-4-1 council],” said Hutchison. “I don’t think we have enough information for that. I couldn’t vote for that at all.”

The provision passed as drafted.

“I was a little disturbed about that,” says Don Hicks’s alternate Jerome Garza, a strong Mexican-American proponent of 10-4-1. “I didn’t really know how it came out that way because that clearly was not what we meant when we voted on it.”

When he learned of the change to the appointment provisions. Lipscomb said “That M F ! He snookered us on that one. I guess I am not surprised. Hutchison wrote a whole new city charter all by himself. Maybe we should change the name of Dallas and call it Hutchison.”

As Act II closed, Ray Hutchison brandished his sword in arrogant triumph, his foot planted squarely on the neck of his opponent.

IT WAS A SCENE STRAIGHT FROM THE Sixties.

Bernice Washington, a black woman from North Dallas, stood defiant before the City Council. She was quickly, spontaneously joined by twenty-four men and women- African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, and Anglos-who surged to the council floor. Dallas was in the midst of its first full-fledged civil rights demonstration in more than twenty years.

Arm in arm they stood, swaying gently together and struggling desperately to remember the words to a tune none of them had sung in a generation:

“We are not afra-a-aid.

We shall not be mo-o-oved.

We shall overcome-To-da-a-a-a-ay.”

Officers fingered their holsters as they ringed the protestors. It could have been Chicago, 1968. But there was an Eighties difference in this protest.

These were not powerless blacks, disenfranchised Chicanos, and ragged, hippie whites. The blacks here included a state legislator, a county commissioner, and three members of the Dallas Independent School District board. Among the Hispanics were attorneys and heads of national organizations with great political clout. The whites were leaders of neighborhood organizations with the power to elect or remove most of those on the council. What a scene it would have made on network television if police had dragged these protestors kicking and screaming from the hall of city government.

Clearly flustered, Strauss declared a recess and huddled desperately with her advisers. It was the last day on which the council legally could call for an August vote on the constitution drafted by the charter review committee. One way or another, the mayor was determined to take that action. No protest could stand in the way.

The solution Strauss and her advisers devised after nearly an hour of discussion would have made Richard Daley, the old boss of Chicago, proud. Council reconvened and, shouting above the freedom song, enacted the resolutions necessary to present 10-4-1 to the voters August 12.

In their frenzy to complete the action and move on, the council majority barely heard objections from Al Lipscomb, Diane Rags-dale, and Lori Palmer.

They heard, but did not heed, a plea from Jim Buerger, who had served on the council only two weeks. Delay the charter vote, Buerger urged. No one had taken time to read the document. The next election date, November, is soon enough for voters to decide. Take time to consider and, perhaps, we can reach a compromise that truly will bring Dallas together.

What Buerger knew-and others on the council knew it, too-was that a compromise lurked close by, waiting to be seized. With no more than another week of discussion, a set of charter amendments that would satisfy almost every faction could have been hammered out.

That compromise was the 12-2-1 plan that originated with Pettis Norman way back in the earliest public hearings conducted by the charter review committee. Buerger knew that it was acceptable to Domingo Garcia and other Mexican-Americans who would lead the fight against 10-4-1. It had the support of Joe May and Al Lipscomb. Diane Ragsdale and County Commissioner John Wiley Price had agreed to back it as well.

And the 12-2-1 plan-which proposed twelve single-member districts, one super-district for North Dallas and one for the southern half of the city, and a mayor elected at large-satisfied the major concerns of most other factions, too.

It assured each resident the opportunity to vote for three council members, a consideration important to the Asian community: Phap Dam says today that he could have supported it. It protected discreet neighborhoods like Oak Cliff and Pleasant Grove from division into two or more districts. It encouraged coalitions to roughly the same degree that 10-4-1 contemplated.

More than that, it provided better opportunity for minorities to seek and win City Council seats than either the existing 8-3 plan or the 10-4-1 proposal. Using the city’s own population estimates as reported by the charter committee, 10-4-1 actually provided a lower percentage of safe minority districts than could be achieved by simply redrawing district lines under the existing 8-3 plan. With 12-2-1, on the other hand, minority representation would increase by at least six percentage points, provided a black candidate could muster the resources to win in the southern half of the city.

It was not a perfect compromise. Not every faction would be pleased. Chances are, for example, that Roy Williams and Marvin Crenshaw, who brought the suit new pending against City Council structure, would not have dropped the action. But chances are better that most who stood before City Council in protest and nearly all of the organizations that fought against 10-4-1 would have closed ranks behind a 12-2-1 compromise.

But the compromise was not to be.

Jim Buerger says he knew before council convened June 28 for that turbulent, climactic session that 10-4-1 was greased. The public hearing that day. council’s only opportunity to hear from citizens concerned about redistricting, was a sham, he says. Despite the fact that twenty-four Dallas residents spoke and twenty-three of them argued against 10-4-1, the decision was already made.

“The appeal from the floor by those who opposed 10-4-1 was a frustrating exercise because their appeals were never considered,” explains Buerger. “One Hispanic leader came to me before the session started and said, ’Can you get 12-2-1?’ I said, ’Nope.’ He said, ’Can we get a delay?’ I said, ’Nope.’ The mayor wanted to put the issue on the August ballot and I knew she already had the votes to do it. I did my best to win some more time, but I knew in advance that it was useless.”

Adds Buerger, “The council doesn’t make its decisions on council day. Decisions are made prior to council day. You would have to work backward to see when the decision was made.”

Though she agrees that 10-4-1 on the August 12 ballot was a foregone conclusion, Strauss offers little help in working backward. She says only that she decided long ago to present to voters whatever plan the charter review committee proposed. The committee heard from dozens of citizens and worked hard for months, she says. It made no sense for the council to second-guess the committee.

The mayor offers even less insight on the question of urgency. Why was an August 12 election critical? Why could the vote not have been postponed until November as Buerger, Lipscomb, Ragsdale, and Palmer suggested? “I wanted to get it on the August ballot,” is Strauss’s only answer. “I just wanted to do it.”

In the absence of insight from the mayor’s own lips, little but speculation remains. Among many blacks and Hispanics, the speculation is that the powerful white forces, represented by Ray Hutchison and his cronies on the Dallas Citizens Council, had simply issued their orders to Strauss and the council. 10-4-1 was as far as they were willing to go in accommodating minorities. And they wanted the controversy ended. Those who hold this view point to Strauss’s rush to shut off debate as evidence that no good-faith discussion was possible. Among those less cynical, the speculation reaches back to the hiatus brought about when Hutchison abruptly disbanded the committee. Perhaps Strauss simply honored her promise to Hutchison that she would force proposals through council unscathed. It may be, too, that support for change among the old Dallas power structure depended tenuously from that same thread.

Some on the council admit they preferred to limit discussion on the package because it contained several goodies for them. “The proposals increased pay for council members, provided them staff, and extended the number of terms they could serve,” one current council member points out. “If they started messing with it, they might have had to be accountable for those things.”

As for her intransigence on the August vote, the most common belief is that Strauss simply was reacting to criticisms leveled at her during her campaign for reelection this year. She had heard herself characterized as wishy-washy and indecisive. She resolved to act decisively on this, the most important issue of her administration, no matter what the cost.

Strauss acted decisively on the reform of governmental structure in Dallas. But the cost was a compromise that might have fulfilled her dream of a city united in a search for fairness and equality.

The final curtain closed on a population divided, family against family and race against race. There was little applause and you could imagine Mayor Annette Strauss uttering the final, searing tragic line penned by Dallas playwright Don Coburn for his drama, The Gin Game.

“Oh, no,” you could hear her moan. “Oh, no!”

EPILOGUE

With one hand, Mayor Annette Strauss coddled a margarita that seemed never to recede from its level in the glass. With the other she clasped the palms of sundry well-wishers and hugged necks with the most exuberant in the crowd.

It was 8:30 on the evening of August 12 and, though the polls had closed only ninety minutes earlier, the “Vote Yes” crowd assembled in the tiny courtyard in front of Martinez Cafe in Oak Lawn knew that 10-4-1 had succeeded with voters by a lopsided margin. “This is a great victory for all the people of Dallas,” Strauss assured supporters who celebrated courtesy of the cafe’s owner, Park Board member Rene Martinez. “An important milestone in the history of the city,” she waxed on.

That Strauss said these things with great conviction suggests she might have made a career as an actress had government not beckoned. That some among her audience-Ray Hutchison, for example-appeared to believe her words hints at the close connec-tion between politics and theater.

Despite her apparent buoyance that night, Strauss had conceded in a private conversation just one week earlier that any victory for 10-4-1 would be a hollow one. She had agreed that, rather than bringing her city together, the new plan had rent it horribly. And she had admitted that, no matter how great its triumph at the polls, the proposal had but the slimmest chance of satisfying legal requirements imposed under the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“I wouldn’t say it was an exercise in futility.” Strauss had said by long-distance telephone from her summer retreat in California. “Any time you get people together to talk about issues and try to find solutions, you accomplish something. But I don’t think we accomplished very much this time. Even if the 10-4-1 plan wins, and I think it will win, it may very well be an empty victory.”

In that conversation, Strauss’s sense of emptiness rested largely on the demonstrations that had occurred weekly since council placed 10-4-1 on the ballot. The first protest in City Hall had been followed by minority leaders marching in chains, by spokespersons standing mute with tape sealing their lips, by an ugly incident in which an elderly woman was injured in a senseless shoving match.

The mayor had seen black organizations without exception reject the 10-4-1 plan she had fought to place before voters. She had seen Hispanic groups split by the vehemence of feeling on both sides of the question. She had heard herself called racist and establishment and tyrannical and insensitive, all the things she never believed herself to be. She knew during the victory party that night that more had been lost in civility and trust than could ever be gained by 10-4-1.

As it turned out, the election victory was more hollow than the mayor could have guessed as she departed that celebration. Analysis of voting results would show that every single African-American precinct had rejected 10-4-1. Nearly all precincts in which Mexican-Americans constitute a majority or near majority had said “No” to the new charter plan. White North Dallas had single-handedly brought the new system into being.

Worse, one of the four ballot resolutions relating to the new charter had, in fact, failed by a narrow margin. That one proposed increasing council pay from the current $3,500 yearly to $30,000 for the mayor and $19,800 for other members. Many blacks and His-panics considered that provision crucial. Only by earning a wage high enough to feed and clothe a family, minority groups insisted, could their chosen representatives ever hope to serve on the council. The failure of the wage provision was seen as a sign that the white majority was determined to retain the old order, the system in which only the wealthy could serve their city without enormous personal sacrifice.

Ironically, minority bloc voting was largely responsible for the failure of the salary provision. Blacks and Hispanics rejected the provision increasing pay along with the rest of the charter package, On the other hand, North Dallas whites who feared more pay would mean higher taxes or who simply did not want to increase wages for what they perceived as inept council members voted no to the salary increase while punching “yes” beside three other charter propositions.

The greatest clouds over the festivities that evening were the legal obstacles that lay ahead. For a 10-4-1 council ever to sit in city chambers, the U.S. Justice Department’s civil rights attorneys would have to agree that the new plan significantly improved opportunities for minority representation. And U.S. District Judge Jerry Buchmeyer would have to rule in the pending lawsuit challenging the old 8-3 system. Already, the city had suffered setbacks in both areas.

Some two weeks before the election, a Justice Department lawyer had told Al Lipscomb that a preliminary assessment of 10-4-1 indicated the new plan was not satisfactory. More than that, the lawyer had said, the city apparently had violated federal requirements by allowing absentee voting before submitting the proposal to her office. Whether those messages had been conveyed to the city’s lawyers is not clear, but the implication was that the feds were not pleased.

Judge Buchmeyer also had made it plain that he was not pleased with the new plan. If 10-4-1 passed, he told city attorneys before the election, he would not exercise his authority to dismiss the pending suit. Instead, he would allow plaintiffs to recast their pleas as a challenge to the new council makeup. In effect, Buchmeyer had served notice that his court, not the charter election, would determine the shape of Dallas government in the Nineties.

Strauss knew that no meaningful victory was possible at the polls. So did Ray Hutchison. “If the Charter Review Committee’s plan passes at the polls,” Hutchison had admitted in an unguarded moment, “all we will have is a group of laws written on a piece of paper. We have spent two years trying to solve city problems ourselves, but the final decisions will be made by the courts.”

In the weeks following that empty victory celebration, the possibility of compromise fell apart. Those on both sides who once might have supported a compromise moved toward their own poles and hardened their positions. As they testified before Judge Buchmeyer, they fought not just for a slice of the pie but for the whole pastry and the oven it was baked in.

The 12-2-1 plan, which once might have served to bring the city together, was all but forgotten. Only Al Lipscomb looked back to consider what might have been. “We were so near and yet so far apart.” he said sadly. “We came so close to doing something good.”

God-ziggety. Forsooth, god-ziggety.