It was the Tuesday after Memorial Day weekend, 1989, and the corporate communications offices of American Airlines’ AMR Corp. raced like a Boeing jet engine. An American Airlines plane at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport had been hijacked by a Cuban national that Saturday, and the phones were still ringing with reporters looking for angles. By this time, the story had been covered to death-from the weather in Los Angeles, where the security breach occurred, to the family background of the hijacker. But a writer at The Dallas Morning News had something fresh and hot. ●For months, the reporter had been prodding the Federal Aviation Administration for statistics on airline security violations for a big story on airline safety. She had recently received the numbers and details on American’s violations, and the news was not good. At D/FW airport alone, American Airlines had allowed at least one security breach a month every month for the past two years, resulting in $130,000 in fines.● The FAA tracks these violations with spot-checks by investigators who pose as passengers and do things like walk onto airplanes or jetways with hand grenades. Things that can result in hijackings. Now the Los Angeles incident gave the reporter a timely hook, and she was armed with the stats. She fired off a forty-inch story while her editor negotiated for more space on the front page. ● But you never got a chance to read that story. ●Late Tuesday afternoon and on into the evening, Lowell Duncan, the communications man at American known as the mouthpiece for CEO Robert L. Crandall, began to place some strategic calls to the News. And when he was finished, the story on American’s security slip-ups had been pulled. When Lowell Duncan borrows the powerful voice of Oz, Dallas knows that Crandall is the man behind the curtain. And the wizard didn’t want this story to run.

Through Duncan, Crandall argued that it would have been unfair for the News to run American’s security stats without including the same figures on other major carriers. Though the security violations of other airlines were due from the FA A, at the time of the hijacking, the reporter had only been able to pry out American’s numbers at D/FW. Obviously, Morning News executive editor Ralph Langer agreed thai the story on American was unfair. He pulled it and into computer never-never land it went.

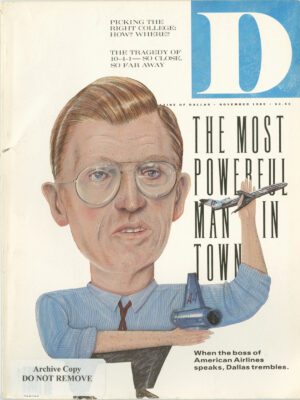

The story that never was is just one more proof that Bob Crandall has become one of the most powerful men in North Texas, influencing people though not necessarily winning friends. With oil and real estate dormant, Dallas has gone into the corporate relocation business, and Crandall controls Dallas’s biggest draw-the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport-with push-button ease. Repeated studies by the Greater Dallas Chamber of Commerce and the Dallas Partnership show that D/FW is a leading attraction of the region both for companies moving to the area and for local businesses wanting to grow. Delta may market its Easy Street from here to Shanghai, but American Airlines is D/FW. For that reason and others, the volatile, chainsmoking Crandall has Dallas quaking in his presence.

Bob Crandall has been in Dallas ten years now, ever since his boss, Al Casey (now retired and an AMR director) relocated the airline here from New York City. During that time, American has grown to be the country’s largest airline and this region’s third largest employer. But Dallas doesn’t know Bob Crandall very well. Like the Wizard of Oz, he’s a mystery. Unlike the bosses of Dallas’s locally built economic engines, the Erik Jonssons and the Jack Evanses of our past, nobody expects Crandall to serve a stint as mayor or chairman of the Dallas Citizens Council. In fact, sometimes it seems that his interests lie elsewhere-in the great beyond of international business or nearer to his other home on Massachusetts Bay. Though the fifty-three-year-old Crandall is an awe-inspiring figure, it is the source of Crandall’s power that is more familiar; in this area alone, American supplies some 20,000 jobs with an attendant annual payroll of $750 million in wages and benefits. When Crandall breathes fire and belches smoke, Dallas, so far, snaps to attention.

THE SMOKE CLEARS MOMENTARILY WHEN BOB CRANDALL puts out one stubby cigarette, then lights another. He storms in and out of the dirty-white clouds he’s created, playing to this room full of business people like a seasoned stand-up comic. In his booming, forceful way, Crandall explains to these members of the University Club why they-business travelers-will always bear the brunt of air travel costs, why they will pay a premium while others super-save. The gist of the argument, shorn of Crandall’s charisma, is that the business traveler is a captive audience. It’s an act Crandall has delivered on behalf of American Airlines many times before, and though grumblings from the audience punctuate his points, he continues, obliterating differing opinions by hammering away with facts and figures and pithy one-liners that the audience is helpless to question. At the end of the speech, the room at the club thunders-not with angry protests but with adoring applause. Crandall has won them over. The up-and-comers here have a new hero.

And why shouldn’t they idolize Crandall and rush to do his bidding? In a city where profit has become false prophecy. Crandall and his record earnings-$476.8 million in 1988, more than double AMR’s earnings in 1987-represent the glory of Dallas Past. The men and women at the University Club remember what it was like to make money hand-over-fist. Just getting this close to a current success story is rejuvenating. And they hope that Bob Crandall’s prosperous American Airlines is indicative of Dallas’s future.

Just say the words “economic development” to this group or many others who have heard Crandall’s rubber-chicken speech, and an exuberant discussion of Dallas-as-international-city will follow. Too depressed to focus on Dallas alone, they look outward with optimism. Here before them today is the new guru for international wannabes in Dallas, Bob Crandall, the man who holds the key to a world economy. Crandall claims that he, single-handedly, can bring that world marketplace to Dallas by increasing American’s international flights.

One of the fastest ways to make Bob Crandall mad, his associates say, is to bring up the subject of what the D/FW airport does for the other major carriers at D/FW, especially in the international arena, where Crandall is pushing hard to expand. A year ago, American surpassed United Airlines to become the country’s number one domestic carrier. Now, international routes are the way to future growth. And Crandall has relied primarily upon D/FW as its vehicle for international expansion.

In 1982, when the U.S. Department of State negotiated a route between London and D/FW, American grabbed it. And since that time, Crandall has been pushing into the international arena as hard as he can before the window slams shut in 1992. That year will mark the start of new trade rules between the twelve countries in the European Community. Crandall believes that U.S. air carriers will be hurt because they are not members of the European Trading Bloc and cannot take advantage of the new code. So he’s grabbing all he can while he can. Between 1984 and 1988, American’s international travel (not including service to and from Canada) nearly doubled-to 13.6 percent of total flights. When Crandall sets priorities, he follows through.

Both the State Department and the local airport board and staff have played important roles in American’s international growth. The State Department negotiates international routes through treaties with individual foreign governments. Airport officials then “lobby” the State Department on behalf of carriers, and the carriers, in turn, make their wishes known to these lobbyists. In the past, Crandall’s wish has been D/FW’s command, because D/FW officials know that if the State Department hands out a newly negotiated route to another carrier, Crandall will take his marbles and play elsewhere. Former and current airport board members point to Seattle, where last year American made tentative plans to open another major hub to serve the Pacific Rim. When a coveted route from Seattle to Tokyo initially went to United, American immediately shelved the plans.

Crandall expects special treatment-and usually gets it-because he is the airport’s biggest customer. American makes up fully 60 percent of D/FW’s business, but according to the numbers, it doesn’t look like the airport gives its other customers even their 40 percent share. Between 1980 and 1988. the airport made twenty-three efforts on behalf of carriers to win international routes from the State Department. Of those, seventeen were for American Airlines and one was for Delta. The airport made a single effort for Lufthansa, one for China Air Lines, one for Air New Zealand, one for Iberia, and one for Thai Airways International. And though American got the majority of the assistance, each plea on behalf of another airline sent Crandall into orbit, some current and former airport board members will say-but only if they can say it anonymously.

And last year, when Mayor Annette Strauss’s huge task force on international development recommended that a number of foreign flag carriers should be added to D/FW if this city were to grow and participate in a world economy, Crandall reportedly left orbit and entered the next galaxy.

Most area business leaders are wary of going head to head with Crandall on the subject of expansion at D/FW. But chamber of commerce chief and D/FW board member Jan Collmer is willing to posit this query: “’The real question is, do we need additional foreign carriers? It could be advantageous to have some price competitiveness.” Collmer asks such questions cautiously, adding quickly, “Bob Crandall is responsible for optimizing American Airlines, and he does a damn good job. We at the board cheer-he makes us look good. We love Bob Crandall.” Airport board members have observed the wrath of Oz when others have spoken out against him. Take 1986, when, not long after airport director Oris Dunham took his post, he told the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce that his worst problem was convincing Bob Crandall that he-Crandall-didn’t run the airport. More recently, Dunham found himself re-explaining a comment about threatened litigation against American if it took the bulk of its business to Love Field. Dunham told a reporter that if airlines rushed to Love Field it would likely start years of litigation. But when the Dallas Times Herald proclaimed in a front-page headline that D/FW would sue American, Dunham had some explaining to do. Though the airport’s relationship with American was bad when Dunham first arrived, he says he has made much headway in getting along with Crandall. So, after the Herald faux pas, Dunham didn’t take a chance. “I called Bob at 0-dark-hundred and explained,” Dunham says. (“That’s before God gets up.”)

Crandall aside, the question of price competitiveness is one that has become an increasing focus of the U.S. Department of Justice. In June, Eastern Airlines’ proposed sale to USAir of eight gates at the Philadelphia airport was opposed because it would have given USAir just under 50 percent control of the airport. At the department’s fingertips was a recent study by the General Accounting Office that reported 27 percent higher rates per passenger mile at airports dominated by one or two carriers. Reregulation is again on the tips of some Congressional tongues.

Bob Crandall’s position on the issue is well known: competitiveness be damned. He may have 60 percent of the airport now, but he would rather have it all. At one of this year’s President’s Conferences, Crandall’s annual fireside chats with employees, he told his people he wanted every plane flying out of D/FW to have an American “AA” on the tail. Already, the American hub at D/FW is the strongest hub-and-spoke operation run by any airline, anywhere.

American’s proposed half-mile-long, $2 billion terminal at D/FW, originally projected to be built by 1996, is the latest stake that Crandall has used to solidify his hold on North Texas. Likewise, the two proposed runways at D/FW, now mired in controversy with airport neighbors, are vital to Crandall’s growth plan. And when a new airport on the drawing board in Denver began to grab headlines, airport board members say Crandall took the opportunity to make a point. Borrowing the voice of Oz, American’s senior vice president of finance and planning, Donald Carty, dangled the shiny marble to reporters, “If Denver gets a big new airport and we don’t get the new runways, it will have an impact [on the expansion] because we’ll be full up.”

THOUGH THE MYSTERY SURROUNDING BOB CRANDALL OFTEN creates a fearful aura like that of the seemingly powerful Oz, it is there that the wizard metaphor ends. When you tug away the curtain, Bob Crandall bears little resemblance to the jolly man who promised to fly Dorothy home in his hot air balloon. Even if his employees affectionately call him “Uncle Bob” when he’s not around, they approach him with trepidation. Longtime employees say they have seen many of their peers fired without due process when they’ve crossed or disappointed Crandall. Employees view their boss with a strange mixture of fear and awe.

Atop Crandall’s narrow-shouldered, diminutive frame sits the head of a bulldog ready to tear into unworthy opponents. His hair is slicked back. His jacket is in the closet; his sleeves are rolled up. Armed with a pack of cigarettes and a cup of coffee, he stares across a table with an expression that says, “I’ll outlast you.”

Dallas Morning News president and editor Burl Osborne can attest to that. “He does not suffer fools gladly. Our discussions have, at times, been very intense,” Osborne says of Crandall. “If you are going to argue with him. you have to do your homework.”

Though Osborne was not part of any “intense” discussions when the story on American’s security breaches was pulled from his newspaper, he was not surprised by Crandall’s response to the aborted story. Osborne and Morning News business editor Cheryl Hall reportedly have gotten to know Crandall by spending time with him over dinner at the Mansion on Turtle Creek. “We spend a great deal of time trying to understand what’s going on with the major players in our community,” Osborne explains, adding that American is an advertiser with the Morning News, though not the largest.

During the last ten years, Crandall has been choosy in letting people get to know him. He has deftly avoided the “High Profile” page of the Morning News and in ten years his name has appeared in the “Today” section a mere five times-and one of those was in an Ann Landers column about air quality on airplanes. Though Crandall and his wife Jan do attend an occasional society function, they are more likely to entertain at home, relying on Jan’s fabled cooking. Among those who say they are Crandall’s closest friends here are people he deals with professionally. His lawyer. Richard Freling of Johnson & Gibbs. His advertising man, Liener Temerlin of Bozell, Inc. His real estate agent, Mim Watson. Crandall’s friends say he is charming and has a wonderful sense of humor. They believe he has gotten a bad rap in the press, where he is likely to end up on one of those “toughest bosses” lists.

Even one of Crandall’s competitors, Southwest Airlines chairman Herb Kelleher, has a friendly anecdote about him. At an airline industry meeting in Washington, D.C., Kelleher says he told the group that it was difficult being little Southwest in the same city with giant American.

“I said it was like being Finland in the shadow of Russia,” Kelleher recalls. ’And Bob quickly fired back, ’There’s one important difference. I ain’t reducing troops.’”

To some extent, Crandall got off on the wrong foot in Dallas. He moved here in 1978, the year the airline industry was deregulated, and soon thereafter American was in a fare war with the local beloved, Braniff. Real estate agent Watson recalls one dinner party she gave to introduce the Crandalls to her friends when Crandall and another guest nearly came to fisticuffs over the Braniff-American battle. Crandall is haunted still, associates say, by a fateful conversation with Braniff president Howard Putnam that later became public. “Raise your goddamn fares 20 percent, and I’ll raise mine the next morning” Crandall said-words that dogged him long after he reached an out-of-court settlement with the Department of Justice, which filed an antitrust lawsuit based on the taped conversation.

But that was the early Eighties, when Dallas could afford to put up its dukes with Bob Crandall. He was another Yankee to Dallas then, transplanted from his Rhode Island roots and his Eastern education in business from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. However, as the city’s economy got weaker and American got stronger, those who didn’t like his bullying have been cowed.

“Crandall has no finesse,” says one former D/FW board member. “He takes a bulldog approach to everything and he pulls off miracles through sheer economic power. He has no sophistication about politics. But it is hard to argue with his success.”

It is not only hard to argue with Crandall’s success, it’s nearly impossible for a city that is constantly approaching his company for a handout. Though some civic supporters grumble that American doesn’t match the generosity of companies like The Southland Corporation, which were born and bred here, Crandall balks at the very idea, pointing out that American gives away millions.

And history would tend to bear him out. Businessman Mort Meyerson discovered that when American gave half a million dollars to the symphony hall that bears his name. Meyerson disagrees with those who think Crandall is less concerned with Dallas’s future than the average CEO here, but he concedes that Crandall is a departure from the Carpenter and Stemmons crowd.

“It’s just the nature of his business-he spends a lot of time out of the city,” Meyerson says.

Or, as one of Crandall’s associates puts it, “The D/FW airport is a tool that Bob Crandall has used to forge the largest airline in the country. The fact that it is in Dallas is beside the point.”

AMERICAN AIRLINES MAY BE THE TAR-get of a takeover,” Channel 8’s Chip Moody announced to the Metroplex. It was late in August, and the bidding for AMR stock had begun. In an industry riddled with aging fleets. American’s newer planes were looking more and more attractive to investors. Sparked by a few late-summer plane crashes, AMR Corp. stock started to soar, meaning Dallas’s already schizophrenic feelings for Bob Crandall were in for a roller coaster ride.

Crandall had just promised an even greater commitment to the area: a $500 million maintenance base at the new Alliance regional airport. And with the Wright amendment, which limits air carrier operations at Love Field, on the way out, Crandall had pledged expansion of American there, too. Now, just when Dallas was beginning to get used to Crandall, would we soon have to contend with some new president and chairman?

The market, doing what it does best, speculated: was the buyer Donald Trump? Or maybe Robert Bass? Would Crandall, who made a mere million last year in compensation, cash in his 38,500 shares of stock for the really big bucks and float away on a golden parachute into the easy life?

Not likely. Early in August, AMR directors, observing takeover battles at competitors United and Northwest Airlines, had bolstered American’s poison-pill anti-takeover defense. And as summer passed, stock market sources speculated that Crandall would welcome competing against those newly leveraged airlines on his own currently unleveraged ground. By the first fall days, it appeared that Crandall had already begun to fight by announcing at an analysts’ meeting that even though AMR had experienced record earnings growth for the past six quarters, the company didn’t expect such records for the balance of this year. In the past, similar gloomy announcements have meant Crandall was reducing pressure for the company to perform because he was up to something, stockpiling a war chest or scheming away at another industry-altering plan-like his controversial two-tiered wage system-that, once set in place, would launch American even further into the black when the danger had passed.

Then an unexpected ally emerged: the U.S. government. Late in September, the Department of Transportation made moves to reduce foreign influence in the takeover of Northwest Airlines, thus greatly reducing the pool of money and potential investors who could threaten the heretofore stable American.

Still, analysts speculate that even Crandall, the golden boy of the industry, will need all of the allies he can get. Even bureaucrats. Because it looks as if he could be in for the fight of his career.

Ironically, a takeover at American wouldbe even more humbling than the bullyingtactics of Crandall. The prospect of a debt-ridden AMR, perhaps run by DonaldTrump, does little for those who enjoy thepeace and prosperity that a huge employerlike American brings to North Texas. Withthat thought in mind, even Crandall’s detractors will be driven to genuflect when hepasses by.

REPORTER’S MEMO

It’s hard to get through the corporate armor that shields most CEOs. And sometimes when you do, it’s disappointing: you scratch the surface and find more brown suit. With Bob Crandall, though. I knew there was more than brown suit, Crandall has excelled at jet speed in a complicated and cutthroat industry while others around him have crashed and burned. And perhaps to protect himself from that devastation, Crandall has built a corporate facade that far surpasses the usual ’”no comment.”

For years, i had asked American’s communications flak Lowell Duncan for an interview. Always 1 was bluntly told: “Mr. Crandall is not interested in having a portrait written.” This time was going to be different, though, because Duncan was actually cooperating. I was assured that spending time with Mr. Crandall would be no problem. So. in preparation, i began to interview business people, fans, and foes. I soon found a city that absolutely trembled at Crandall’s economic power. No one wanted to talk because they feared it would jeopardize American’s current involvement in Dallas. What if he got upset and washed his hands of us altogether? We’d be lost.

One person I called was Mort Meyerson. I knew that American had contributed mightily to the symphony hall, and I figured that Meyerson was a Crandall fan. Also. Meyerson is known as a tough, straight shooter; he could offer some insight into Crandall’s hold on the city. Little did I know just how sensitive Dallas’s leaders are to Crandall’s feelings. Meyerson began to defend Crandall with a zeal usually reserved for the pulpit. And not long after our conversation, he was on the phone to Crandall warning him of the so-called “hatchet job” that D had planned.

Then our phones started to ring. What did we think we were doing? Didn’t we realize what Crandall did far this city’? Didn’t we know how many people this story-and Crandall’s reaction to it- could affect?

My next call was from Lowell Duncan’s office. The interview with Crandall was promptly canceled and I was told to begin again in the corporate communications quagmire. First there was a meeting with Crandall and Duncan to discuss a possible meeting. Then I hand-delivered clips and questions-an unusual concession-in preparation for this potential meeting. And then I called, but Duncan was in a meeting. So I wailed. And called. Still in a meeting.

Finally, with the help of my editor I reached Duncan, who saidthat he thought we had gone away. We hadn’t. Ever positive, heassured us that a meeting was still being considered. So we called.But Duncan was on the other line. We waited. We called again. Westill thought it was vital to get Crandall’s direct input into our story.But when D went to press. Duncan was in a meeting. And Cran-dall was…Crandall. – S..G.

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman