DURING NEARLY FIFTEEN HOURS OF JURY DELIBERA. tion, Tom Gaubert had not been alone. But when the federal marshal emerged from the jury room and walked toward the judge’s chambers. Gaubert was left silting by himself in the hall of the federal courthouse. And for the first time during his three-week trial-for the first time in his five-year ordeal, Gaubert says-he was frightened.

Gaubert, a Dallas real estate developer and former savings and loan owner, had been charged with five counts of criminal fraud in connection with a real estate deal he did in 1983 with an Iowa thrift. The indictment against Gaubert accused him of taking $5.6 million of an $8 million loan disbursement from Capitol Savings and Loan Association in a so-called “land flip” scheme.

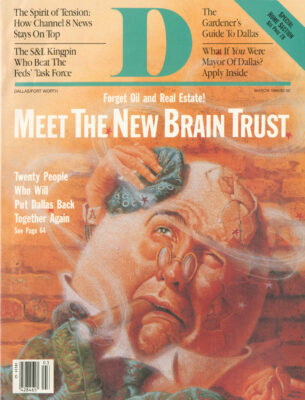

Gaubert was brought to trial in October of 1988 by the highly publicized savings and loan “task force’-a joint effort of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation set up in the spring of 1987 to indict and prosecute participants in what the government believes to be widespread fraud in the industry. The task force had a formidable record when it got around to Gaubert. Federal prosecutors had a perfect conviction rate. They had won four convictions through trial and had secured guilty pleas on everyone else indicted. Tom Gaubert was the fifth person tried on what is now known in Dallas as the task force “hit list.” Some 700 people-most of them Dallas businessmen-are said to be under the slow scrutiny of the task force.

Gaubert’s entourage had done a solid job of keeping his spirits high during his trial and the jury deliberation. At one point, his children placed their hands against the door to the jury room and bowed their heads to pray silently, to send positive thoughts through the heavy wooden doors to the men and women deciding their father’s fate. They were joking in part, trying to cheer up their dad, Gaubert says, but their prayers were heartfelt.

During another slow hour, Gaubert’s attorneys listed sixty-five reasons why he should be found innocent and three reasons why he should be found guilty. On the “guilty” side of the ledger, they came up with this: if Gaubert were convicted, they joked, it would be good for the prosecutor’s career. Also, Gaubert would be a positive role model for other prisoners, and when he go) out, he would no doubt set about reforming the prison system.

But when that federal marshal emerged from the jury room and walked down the hall to the judge’s chambers, no one was around to joke or pray with Tom Gaubert. His son had taken Gaubert’s mother back to the hotel, and his attorneys were walking around the courthouse. Gaubert stood up, followed the marshal down the hall, and waited outside the judge’s door.

“And then I heard something that scared me to death,” Gaubert says. “The judge told the marshal that he had better get the probation officer. I thought we had lost. Why else would they need a probation officer?”

Gaubert went into the courtroom alone, sat at the defense table, and prayed. Given the alleged offense and the amount of money involved, he would surely have to do some jail time if convicted. He was forty-eight years old and weighted with responsibility; he was engaged to be married to a younger woman and was the caretaker of his elderly mother. But if he got the maximum for each count of fraud and had to serve the terms consecutively, his plans would have to change. He would be in federal prison for the next nineteen years.

“I didn’t say anything to my attorneys or my sons when they got there. The judge asked me to stand. All 1 could think about was that my sons were sitting behind me. and I didn’t know what I was going to say to them if they found me guilty.

“The next thing I knew my youngest son was crashing over the railing and literally tackled me,” Gaubert says. “I hadn’t heard it, but the verdict was not guilty.” Gaubert didn’t know that the judge hears the verdict for the first time when the foreman reads it aloud in the courtroom, and a probation officer is normally present.

Gaubert, still stunned, walked out into the hall to thank the jury of nine women and three men that had found him not guilty. He eagerly shook each of their hands, smiling wide, his white teeth showing through a salt-and-pepper beard. But when the jury was gone, he says, no feeling of joy remained.

Not one to keep his mouth shut-even when his lawyers tell him to-Tom Gaubert had professed his innocence with vehemence from the beginning. For nearly five years, he had defended himself in business and social circles in Dallas and in Washington, D.C., where he is an active Democratic fundraiser. Gaubert had spent $2.5 million dollars on his defense. But when he finally won, he says, he didn’t feel like celebrating.

IF YOU PLAY A SIMPLE WORD ASSOCIA-tion game in Dallas these days and start with “S&L scandal” or “land flip,” after your teammates have worked through “1-30 condos,” “Danny Faulkner,” and “Ed McBirney,’1 someone will probably say “Tom Gaubert.” Gaubert’s life during the last five years has been very high profile, first as a successful residential builder, then as the owner of the fast-lane Independent American Savings-and Loan, and later as a cigar-smoking, big-talking, pot-bellied Democratic fundraiser for Speaker of the House Jim Wright. Majority Whip Tony Coelho. and their favorite political action committees.

Gaubert was acquitted in Iowa, but he returned home to a still-skeptical Dallas that asked, “How did Gaubert walk?” Regardless of that jury’s decision, he had long ago been found guilty of S & L-related crimes in Dallas-purely by association.

“These guys are crooks. I’d put them in jail.” Ross Perot told the National Press Club shortly after the presidential elections. Perot’s feeling toward S&L owners in the Southwest was both an echo and a shaper of popular opinion. With analysts predicting that the savings and loan industry is as much as $100 billion in the hole, it has become much easier for the public and the government to blame the mess on “crooks” rather than admit that deregulation, coupled with very complicated and devastating market conditions, has contributed to an industrywide collapse, Ridding the system of those crooks promises a quick fix that will calm angry natives, while solutions to a regional economic depression are elusive and could take the better part of a decade to make a difference. But with pillars of the community like Ross Perot making such sweeping statements, defense attorneys for some of the 700 so-called crooks on the S & L task force hit list say it’s nearly impossible to find a jury in Dallas that doesn’t have “put them in jail” on the brain.

Given that pervasive attitude. one answer to the question-how did Tom Gaubert walk?-is that he got lucky; he wasn’t tried in Dallas. Though the S&L task force had racked up that perfect record before it got to Gaubert, defense attorneys speculate that a significant number of those who pleaded guilty did so because they couldn’t afford a defense. And at least one of those victories for the government-among the Vernon Savings crowd-was more of a prostitution case than an elaborate financial scheme. One savings and loan official was convicted of supplying female companionship during the deal-making process. It’s simply easier in Dallas-where the public eye and the daily press have obediently followed the government’s fingerpointing-for the task force to get convictions.

The venue of Gaubert’s trial, though, was Des Moines, Iowa, because Capitol Savings and Loan Association is located in nearby Mount Pleasant. And in Iowa, the word association game is played a little differently. Say “savings and loans” there, and teammates will follow with “foreclose on hardworking farmers.”

A veteran financial reporter at The Des Moines Register says that the person on the street in Des Moines doesn’t have a strong prejudice when it comes to the S&L debacle because the real estate-related mess hasn’t been publicized there to the extent it has in Dallas. So when federal prosecutors tried to paint Tom Gaubert as a crooked real estate fat cat from Texas taking advantage of an S&L, the jury wasn’t predisposed to buy it.

Nor is “land flip” part of everyday conversation in Des Moines as it is in Dallas, where the words automatically carry a negative connotation. And since a so-called land flip was the crux of the Gaubert case, federal prosecutors had their job cut out for them. At one point in the jury deliberations, the foreman wrote a note asking the judge to explain again exactly what Gaubert was supposed to have done. The judge obliged, though it was clear at that point that federal prosecutors hadn’t done their job of preTom Gaubert’s case is a fairly typical one for the S&L task force. But because he is the most prominent S&L figure brought to trial so far. the feds’ first loss is a big one. Those keeping a close watch on the task force’s activities in Dallas say the Gaubert loss has made task force investigators here attack their work with a new. more powerful vengeance. The many people who have imagined themselves in Gaubert’s place at the defendant’s table are in a quandary, unsure whether to be encouraged by Gaubert’s acquittal or afraid of the task force’s renewed fervor. But Gaubert’s case does lend credibility to the claims that the task force and its “hit list” both exaggerate the problem and lend nothing to a solution.

“It seems inconceivable to me that the amount of fraud they are alleging took place.” says a Dallas mortgage banking executive who has worked with many of the people on the task force’s long enemies list. “It has gotten to the point that honest busi-nesspeople are afraid to do business in Dallas. And that is really frightening.”

“The only crime that most of these guys committed,” says another industry insider who has done consulting work for the government, “was to have too big of an ego. Maybe they were stupid. They thought this was the land of milk and honey and they couldn’t fail. But then tomorrow came and their deals based on inflation fell apart.”

Both men, not wishing to attract task force scrutiny, prefer to speak anonymously, which seems to be the name of the game in Dallas these days: keep your mouth shut and your eyes to the ground, put lamb’s blood on your door, and, like the Angel of Death, the task force might pass over you and take the next guy. But Tom Gaubert never took that advice. Not only did he not keep his mouth shut, he sued the government and then refused to roll over and play dead when they indicted him. A close look at his case-putting aside sweeping assumptions that find him guilty by association-tells a frightening story of the S&L task force’s role in Dallas business.

TOM GAUBERT STILL WONDERS IF HIS fight with the federal government will ever be finished. It began back in 1983 when Gaubert stormed into the S&L business the way he always storms into a room- a big smile on his friendly, bearded face, hand outstretched, ready to get to work. Gaubert had acquired Citizens Savings Association of Grand Prairie, a sleepy little S & L that primarily made home mortgage loans. Like the other entrepreneurs that federal regulators encouraged to get into the business. Gaubert changed the character of Citizens, starting with the name. Gaubert called his thrift Independent American Savings Association and moved its main office to Dallas. Independent American, under Gaubert’s direction, entered the world of land, apartment, and other commercial loans.

When Federal Home Loan Bank Board Chairman Ed Gray came to Texas to make policy speeches encouraging new savings and loan owners to grow. Gaubert obliged. Apartment loans at Independent American grew from zero in 1982 to $76.1 million in 1985. Other commercial real estate loans grew from $4.2 million in 1982 to $221.2 million in 1985. Land loans grew from $193,000 to $188.8 million in that period.

Today we look at those numbers with the frightening hindsight that the market would soon crash down upon Independent American and all of the other banks and savings and loans that had the majority of their loan portfolios sunk into real estate. But in the giddy days of the boom, neither developers, S&L owners, nor regulators saw it coming.

Much of Independent American’s growth-and later, its problems-was the result of a regulator-endorsed merger with Investex, a troubled savings and loan in Tyler. The Investex-Independent American marriage had a very short honeymoon-by the end of the third quarter of 1986, Independent American was showing $512.8 million in loan losses. And by that time, Tom Gaubert was no longer running the show. Regulators had asked him-the man they had handpicked to save Investex-to step down pending investigation of none other than that land deal with Capitol Savings in Iowa.

other reasons that the federal government chose to indict him for fraud. In 1985, the land deal sour, Capitol filed civil charges against Gaubert. since he had brought the loan to the institution. In the summer of 1985 Gaubert paid Capitol $7 million to settle that suit out of court. He assumed the matter was finished.

But when regulators wouldn’t allow Gaubert back into his leadership role at Independent American, he cried foul play. In 1987, Gaubert filed two suits against the Federal Home Loan Bank Board leadership, alleging that he had been led down the primrose path with Investex and then fraudulently deposed from his savings and loan. Gaubert says he invested $40 million in cash and real estate in Independent American and lost it because of the negligence of government-appointed managers who ran the S&L into the ground after he stepped down.

Whether or not any of that is true, it is true that three months after Gaubert filed suit against the government, the government indicted Gaubert on the Capitol deal-a case that had been settled out of court nearly three years earlier.

“In our criminal case,” Gaubert’s Washington, D.C., attorney Abbe Lowell says, “we pointed out to the judge that it was a significant coincidence that an investigation that had not been pursued for three years got on the fast track as soon as Tom started making waves.” Maybe the government thought a fraud indictment would still the waters.

ALAND FLIP IS NOT ILLEGAL,” SAYS Richard M. Fishkin, the trial attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice who heads up the S&L task force in Dallas. “The illegality [in the Gaubert case] was not based upon the transaction per se, but on an attempt to make it look like something else.” In other words, it was perfectly legal for Tom Gaubert to put a 125-acre tract of land in South Dallas County under contract at forty cents a square foot late in 1982. It was legal for Gaubert to close that deal on April 16, 1983, the same day that he sold forty-four acres of the land to Garland developer Ernie Hughes for $2.55 a square foot. It was also legal for Gaubert to arrange financing through Capitol Savings and Loan Association for twenty-two borrowers, who intended to build a condo project called Chesswood, to purchase those forty-four acres on the same day from Hughes for $5.25 a foot.

That is a land flip. What makes that land flip illegal, Fishkin maintains, is that Gaubert hid his participation in the deal from the savings and loan, and thereby deceived the S&L and pocketed $5.6 million of the $8 million loan disbursement to the twenty-two borrowers, most of whom were Dallas busi-nesspeople. The prosecutor also believes that Gaubert kept his affiliation with the deal from Capitol in order to defraud it when the loan was not repaid. Falsified appraisals that inflated the land value could also make a land flip illegal, Fishkin explains.

The bulk of the testimony in the Gaubert case revolved around the issue of whether or not savings and loan officials at Capitol knew that Gaubert was involved in the real estate deal. In his opening statements. Abbe Lowell, Gaubert’s lead attorney, told jurors that evidence would show there were at least twelve instances when Capitol officials were told of Gaubert’s involvement. But in his closing statements, Lowell had to tell the jury that he had misstated himself. He had shown fifteen instances.

The most important of those, Lowell says, was correspondence sent to Capitol from the paralegal of Dallas real estate attorney Scott McDonald-who represented Gaubert and Capitol in the transaction-spelling out the tiered land sale and Gaubert’s role in it.

According to several sources who wish not to be named, McDonald’s testimony against Gaubert was solicited by prosecutors in exchange for a grant of immunity-one of the federal task force’s most common moves. By getting one participant in a deal to admit he is guilty of something, prosecutors imply that others are, therefore, guilty because they associated with fellow number one. In McDonald’s case, his “guilt” was not even germane to the Gaubert indictment. Investigators had questioned McDonald about $961,922 in payments that the twenty-two investors received from Gaubert as inducements to participate in the deal. Though real estate insiders call such payments “working capital to investors to improve collateral,” the FBI calls them “kickbacks.” Such payments are not strictly illegal-Gaubert’s attorney equates them to rebates-but McDonald denied knowledge of those payments to federal investigators, sources say, and thus got himself in trouble for lying. (McDonald says his attorneys advised him not to speak about the case for publication.)

It turned out that, as with most of the prosecution witnesses, McDonald’s testimony was not very damaging. While being questioned by Lowell. McDonald told the jury that he thought Capitol knew that Gaubert was buying the property, and that Gaubert never told him to mislead Capitol in any way. The government’s best witness was former Capitol vice president Dale Longwell, who told the jury that he would not have recommended Capitol fund the loan if he had known Gaubert would pocket $5.6 million from the deal. Capitol had been criticized by federal regulators for committing too much money-$32 million-to a Gaubert project in California. And Longwell was, in retrospect, trying to make himself look like a prudent banker.

Longwell told the jury about a key board meeting on March 30, where he said that Gaubert denied having an interest in the project being financed. This was the crux of the government’s case-the best shot.

But Gaubert’s attorneys maintain that Gaubert was being truthful since he was not participating in the development of the property, only in its sale.

Then prosecutors introduced evidence that Longwell received a $150,000 personal loan from Gaubert shortly after the Chesswood loan was approved. In fact, Longwell and Gaubert had several personal dealings; in one, Gaubert helped Longwell buy $120,000 of oil company stock with the entire amount being financed.

But despite any damage that Longwell did to Gaubert in his testimony, Lowell was able to use him-and other prosecution witnesses-to get key information about Gaubert to the jury. In cross-examination, Longwell admitted to the jury that Gaubert had been introduced to him as an expert in working out real estate problems and that Gaubert had actually helped Capitol make millions.

The Chesswood loan, as it turned out, was one of those instances when Gaubert was helping Capitol out of a tight spot. Since federal regulators were critical of the $32 million commitment to a Gaubert development in California, Gaubert proposed that Capitol shift that commitment to the Chesswood deal. Since it involved twenty-two investors, loans could be split into $1.4 million chunks, thus appeasing regulators, who signed off on the deal.

To further prove that this land flip was legitimate, the defense showed the jury Capitol’s own appraisal records on the Chesswood land. The appraisals showed the developed land on the deal was worth as much as $6 a foot. Daniel L. Jackson, a Dallas CPA, used Dallas County land sales records to show the jury that Gaubert sold the land at a fair market price.

By the time the prosecution rested, the evidence and testimony presented so favored Gaubert that defense attorneys discussed not even putting on a case. One veteran newspaper reporter covering the trial says he quit attending at that point because the government’s case was so weak that he was virtually certain that Gaubert would be acquitted.

Of course, the defense did present a case-it would have been a shame to waste the stable of character witnesses straining at the bit to help their friend Tom Gaubert. Gaubert says that when the news got out that he would be going to trial, eighty-nine people volunteered to be character witnesses for him. “That meant a lot to me,” he says, “that that many friends would come forward.” The volunteers varied widely, from a sergeant major whom Gaubert had known in the Army thirty years ago, to Dallas Criminal District Court Judge Ron Chapman, to Texas State Treasurer Ann Richards, who testified that Gaubert is “honest, law-abiding, and a gentleman. . .who has always promoted women in his organization.”

Richards, who delivered the keynote speech at last year’s Democratic National Convention, was one of four high-profile Democrats Gaubert’s lawyers said they could call on to testify. The others were former Vice President Walter Mondale, former presidential candidate Rep. Richard Gephardt, and Charles Mannatt, former national party chair.

Character witnesses for Gaubert had a wealth of charitable deeds to draw from to convincingly portray him as a man with a basic desire to help people. Gaubert’s contributions to various nonprofits in Dallas have received little attention compared to his roles as businessman and political fundraiser. Gaubert served from 1983 through 1985 as finance chairman of the North Texas chapter of the March of Dimes and was one of several people who attempted a twelfth-hour rescue of Bishop College. But, says Dallas attorney Bob Greenberg, a close friend of Gaubert’s, most of Gaubert’s giving to the Dallas community has been anonymous.

’”I can’t tell you how many Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners that Tom has donated through pastors. If there’s a community need and he’s able to respond, he does,” says Greenberg, who served as local Democratic party chairman from 1982 until 1984.

“He’s just an incredibly generous man,” Greenberg says. “Not to downplay his inten-siveness in business-but I just don’t think he gets a thrill out of making deposits.”

Though Greenberg didn’t testify as a character witness for Gaubert, Dallas attorney Lisa Blue, who helped pick the jury and interview witnesses for the defense, says other witnesses painted a consistent picture of an honest man. “I knew we could win if we could paint Tom the way he is,” Blue says.

Gaubert never got the chance to tell the jury his story. His attorneys decided not to put him on the stand. “He wanted to testify, but Tom can be very volatile and this was a very emotional time for him,” Blue says.

“That was the most difficult decision I had to make,” Lowell says. “An attorney is always second-guessed on that. If a client is acquitted, you are a genius. If not.. .”

We’ll never know what most influenced the jury members because they made a pact not to speak to anyone about the trial. That may have been a wise decision. Though press attention is waning, attorneys representing many of the other 700 people on the S&L task force hit list are still intensely interested in the Gaubert trial. With Gaubert acquitted-contrary to public opinion that found him guilty-his trial provides some insight into their own clients’ defense.

WE ONLY PROSECUTE CASES WE think we can win.” says Richard Fishkin. Though he’s sitting in his own rather plain office, the government attorney isn’t comfortable because he’s talking about his task force’s first big loss. He says he won’t rehash the Gaubert case because “we are not here for publicity, we are here for results.” Then he goes on to explain the difficulty of prosecuting these S&L cases. “You have to pick something simple that can be clearly presented to a jury. The problem is these cases take a long time to put together-two or three years-you get rushed by the statute of limitations |five years].”

In the Gaubert case, the government had to indict before the end of March 1988 because the alleged crime was committed in March of 1983. So in his roundabout way. Fishkin is saying the task force got rushed in the Gaubert case-bureaucracy, after all, works slower than private business.

But can we assume that this is the government’s best shot against Gaubert?

“We had a reasonable expectation of success,” Fishkin says. “And like I said, we only prosecute cases we think we can win.”

It’s not easy to get a straight answer out of these guys. But assuming the feds’ actions speak louder than words, many people in Dallas don’t like what they are hearing.

“Until the task force gets finished with what it is doing around here,” says another Dallas businessman who doesn’t want to make waves, “we are not going to be able to go about our business without looking over our shoulders. Everyone is so bloody cautious, it’s hard to get an honest deal done.”

An adviser within the industry thinks that at the most there may have been a core of a hundred people in the entire Southwest doing fraudulent deals with savings and loans. “So going after the whole town,” he says, “is just a waste of taxpayers’ money.”

But if the task force’s role is one of intimidation, then those dollars are being effectively spent. People in the savings and loan and real estate business in Dallas are as quiet as they ever have been.

The same is true of Tom Gaubert. These days you can find him riding around town in his Jeep Cherokee looking at real estate or in his office helping his attorneys work on his lawsuit against the government. They hope one of his suits will be returned to Judge Robert B. Maloney’s federal district court this month. For that reason, and because of threat of further prosecution, Gaubert is at least trying to take heed of his attorney’s warning, keeping mum and ducking most reporters’ inquiries.

“If you make yourself a lightning rod,” says Abbe Lowell, “you’ll get struck by lightning.”

That’s good advice for anyone who might be on the S&L task force hit list. Especially if they don’t have $2.5 million to defend themselves in court.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte