JIM MCLENNAN, A PARTNER IN THE Dallas office of Kenneth Leventhal & Company, recalls an incident at a recent seminar on foreign investment. The topic was doing business with the Japanese. Suddenly a local businessman in the audience stood up, and, obviously exasperated, interrupted one of the panelists, an analyst from Goldman Sachs.

“Listen,” the man shouted. “I was always taught ’When you’re in Rome, do as the Romans do.’ So how come when the Japanese visit here, they continue to act like they’re in Japan? I’m always hearing how I should never offend them; how I should bow with my arms extended, palms flat on my thighs; how I should always give them a certain amount of personal space; how I should treat their business cards with great respect, and so on and so on and so on. My question is: why don’t they do the kowtowing?”

The Goldman Sachs man sighed. Finally, he said quietly, “Because they, my friend, are the ones with the money.”

The Japanese, as exporters and notoriously stingy savers, have amassed billions of dollars of spending money (they’ve even acquired 25 percent of Goldman Sachs). By contrast, we Americans, as importers and notoriously extravagant spenders, are deep in debt. “Time to start selling the family jewels,” says U.S. Congressman John Bryant (D-Dallas), who has made a career, of late, out of crying in the wilderness against Japanese ambitions.

Nowhere are those family jewels better displayed than in Dallas, the quintessential buyer’s market. Millions of square feet of office space sit vacant. Hundreds of companies sit undercapitalized. Thousands of people sit jobless. Easy pickin’s. But are the Japanese buying? Conventional wisdom says no. A careful examination of who’s kicking what tires reveals otherwise.

“Just a year ago they were totally redlining Dallas-Fort Worth,” says Fred Brodsky, whose real estate firm has patiently worked with the Japanese for more than a decade. “Now they’re saying, ’Show us some property.’ They are definitely tempted to buy.”

Trouble is, the Japanese are notoriously fussy shoppers. They are hearing some high-powered sales pitches, yet they are not easily impressed. You can see them in the lobbies of the Anatole or The Fairmont, invariably in groups, clad as always in dark suits, white shirts, and ties of subdued colors, conversing with each other in Japanese as they wait for some all-too-eager Dallasite to pick them up in his Mazda sedan and drive them over to inspect another “steal” of a property.

The Japanese are prepared to do deals. But they will deal from strength. There is fear that capital-starved Dallasites will deal from desperation.

Around the country, concern is rising that the U.S. is mortgaging its future. The number of Japanese real estate purchases in the U.S. is mounting so rapidly ($16.5 billion worth last year) that Coldwell Banker Commercial Group recently announced, “It is inescapable that, considering the scope, the scale, the rapidity, and methodical nature of their commitment, the Japanese will become, at some point, sooner than we may anticipate, the dominant force in the U.S. commercial real estate marketplace.”

That announcement came shortly before the Japanese bought a sizable chunk of Cold-well Banker Commercial Group.

THE FIRST MAJOR WAVE OF JAPANESE IN-vestment in U.S. real estate came in 1985, landing mostly on the East and West Coasts. Those investors were primarily large institutions, including insurance companies and trust banks, capable of plunging upwards of $100 million into a project. They were spurred by changes in the tax code, the rise of the yen, reserves of cash, liberalized foreign investment rules, the perceived security of the U.S. market-and especially by skyrocketing real estate prices in Tokyo, where yields had dropped to the 1 to 2 percent range, compared to the 8 to 10 percent supposedly available in U.S. cities.

Compared to Tokyo, even the most upscale U.S. real estate markets were cheap- and wide open. The Japanese plunged fortunes into office buildings in “Bowash.” the Boston to Washington corridor, the epicenter of which is Manhattan. Even more extensive were their investments in Honolulu, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, all of which happen to harbor large Japanese-American enclaves.

Any community that begins to lose control of its own fate feels threatened, In Los Angeles and Hawaii. Japanese domination of the residential and commercial real estate markets has aroused a furor, triggering legislation aimed at limiting foreign investment. “Do we want our corporate decisions made on the other side of the Pacific Ocean?” asks a pamphlet distributed by “Concerned Citizens” in Los Angeles. “Do we want a foreign country to have the power to hold us hostage by threatening to suddenly say sayo-nara and pull out of our city? Do we want foreigners lobbying our government through the PACs of companies they’ve bought?”

Dallas, so far, is nowhere near such a panic point. “We’ve got plenty of room here for Japanese investment,” says Dallas Citizens Council chair Bill Solomon, echoing a common sentiment among city leaders. Coldwell Banker has estimated that only 17 percent of downtown Dallas office space is owned by foreigners {of any nationality), about the same as Atlanta, Miami. Denver, or San Francisco. According to a study by Leventhal & Co. accountants, we should feel insulted. Leventhal ranks Dallas only seventh in the nation among major cities, with $1.46 billion of its real estate belonging to Japanese. Last year just 3 percent of Japanese real estate investment nationally went to Dallas, or some $505 million in Japanese capital, including $230 million in the financing of Texas Commerce Tower by a joint venture among Equitable Life, Nippon Life Insurance Co., and Trammell Crow Companies. Much less sovereign is downtown New York, which is 21 percent foreign-controlled; Minneapolis at 32 percent; and Houston. 39 percent. Los Angeles, site of the 1984 Olympic Games, is 46 percent foreign-controlled.

So far, the Japanese have not participated in the Dallas downtown office market as much as, say, the British. In fact, as investors, they are less tigerish than their Far Eastern neighbors in Taiwan. Korea, and Hong Kong-all of whom detest the Japanese. However, the Japanese are by far the wealthiest investors in the world. If they wanted to, they could be in the driver’s seat in Dallas.

And there’s every indication that they are reaching for the steering wheel. Even the research companies will admit that they may not have the complete picture. Leventhal doesn’t include factories and manufacturing plants in its survey, and dozens of such facilities are sprouting up and spreading around the city. And the firm admits there may be some office building investments of which it is unaware.

The secrecy of it all worries some prominent Dallasites, although they won’t admit it publicly. “Dallas, without a doubt, needs billions of dollars in capital.” says a corporate senior executive. “But the people of Dallas have a right to know where the hell those billions are coming from and where they’re going-if for no other reason than so the city can adjust its planning and policies accordingly. If this city learned any lesson at all from the recent building boom and bust and the accompanying S&L horror show, it’s this: capitalism has no conscience,”

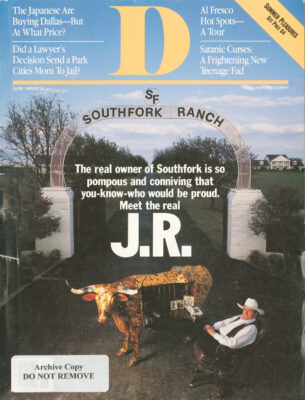

“Secrecy”-privacy, if you will-is built into the Japanese psyche. Many a Japanese will tell you that the Dallasite they most detest is J.R. Ewing, Gloater. and that the Dallasite they most admire is Tom Landry. Stoic Revealer of Nothing. They believe that gloating will get you nothing but resentment. Local Japanese investors winced at Jerry Jones’s public exultation upon taking over the Dallas Cowboys, and shook their heads when Texas government officials celebrated after winning the site for the super collider. Pride, they know, goeth before the backlash.

Japanese executives not only refuse to boast about their interests in Dallas/Fort Worth, they refuse to talk about them. For such an unassuming people, their surplus of cash and their far-flung holdings have caused a genuine embarrassment of riches. Ever cautious, Japanese investors expect absolute confidentiality on the part of anyone they do business with, so don’t expect to hear someone blabber over lunch that such-and-such tower has gone over to the other side. Likewise, don’t expect to find out about every company acquisition by scanning the announcements on the business pages; the U.S. real estate subsidiaries of many Japanese corporations use initials like the innocuous NLI Properties Inc.-a new name replacing the more identifiable Nissei Realty.

Tracing Japanese interests requires a Mr. Moto with an MBA. Like other investors, they do all sorts of complex deal structurings and financial arrangements that are sometimes difficult to detect.

“There is no “typical” Japanese investor,” says Leventhal’s McLennan. Indeed, there is a veritable myriad of types: life insurance companies, construction companies, development companies, trading companies, trust banks, securities firms, commercial banks, leasing companies, and, excuse the word, individuals. Also, many related or hybrid organizations exist, among them consulting firms, brokers, and merchant banks.

The newest Japanese players are small and medium-sized companies and individuals, and the huge Japanese pension funds. Smaller Japanese investors simply can’t afford to invest in their own country’s real estate anymore. The most expensive street on earth is the Ginza, located at the crossroads of Tokyo’s centers for business and nightlife, It now fetches a whopping $650 per square foot, more than a 60 percent increase over last year. By comparison, the former most expensive street on earth. New York’s East 57th Street, now brings in $435 a square foot. Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills draws $225.

The average lease in downtown Tokyo runs some S175 per square foot of space compared to $17 in Dallas. And because tenants in Tokyo must make an initial security deposit of one year’s rent, a down payment of $875,000 is required just to initiate a rental of 5,000 square feet. With those prices, Dallas is looking better every day.

Add to that the heretofore unleashed power of the Japanese pension funds, now allowed to invest 20 percent of their assets abroad, versus the old 3 percent. That means billions more bucks will be sneaking into something somewhere, much of it under the auspices of Japanese trust banks. The chances are very good that that somewhere is here.

MUCH HAS BEEN MADE OF THE JAPANESE “herding instinct.” They slowly follow each other into a market, quietly building up a presence until achieving a critical mass of interests, all of which subsidize each other. That process has been taking place in Dallas/Fort Worth, where at least 135 Japanese firms operate. Most of them are just two- or three-person sales or trading offices, but some are fast-growing. “Users often end up as landlords,” says Don Williams, managing partner of Trammell Crow Companies. “Japanese tenants tend to want to own the building they’re in.” As they keep expanding, Japanese companies are expected to buy up more and more industrial properties, which consist not only of warehouse space but also facilities for high technology, research, and development.

And more and more, Dallas’s real estate companies, weary of battling their creditors, are poised to receive the cash-heavy visitors. One such firm is Vantage Companies, one of the nation’s largest developers and a specialist in industrial projects. Like Trammell Crow, Vantage CEO John Eulich has paid his dues with the Japanese, bringing them in on deals around the U.S., letting them learn the intricacies of the U.S. market. And like Crow. Eulich had to restructure his company recently and is glad to have rich Japanese companies for friends these days.

In July 1986, Vantage formed a co-subsidiary-a design/building firm named TaiVan-with Taisei, a $10 billion-a-year Japanese construction company that has built such projects as the Olympic Stadium and Disneyland in Japan, as well as the Sheraton Grand Hotel in Long Beach, California. The executive vice president of TaiVan, Ernest H. Randall Jr.. has been working with Eulich since 1970. He was involved in the site selection, acquisition process, and first-phase design of the new Fujitsu complex to be built in Richardson on one hundred acres bought from Ross Perot.

Lately. Japanese manufacturing companies, highly successful in the U.S. market because of their superior efficiency and quality control, have been broadening their horizons here, creating plenty of business for Vantage and others who have earned their trust over the years. In Las Colinas, both Hitachi America (computer chips) and NEC Corp. (telecommunications) are extensively expanding facilities that employ hundreds of workers. In Piano, Murata Business Systems (fax machines) recently moved into its new corporate headquarters. Legacy business park. Sanden International (automotive compressors) is busy transferring its headquarters to a new $60 million complex in Wylie, built on ninety-four acres.

Other major Japanese companies with large operations locally include C. Itoh Cotton in Dallas, Canon USA’s sales office in Irving, Fujitec America (elevators and escalators) in Dallas, Nissan’s distribution center near the D/FW Airport, Hitachi (semiconductors) in Irving, and Matsushita Electric Corp. (makers of Panasonic) south of D/FW. Uniden (cellular phones) is moving its U.S. headquarters from Indianapolis to near D/FW. Many of these firms are in the Metroplex largely because of the area’s central location and distribution facilities. But the computer and electronics companies are here to interact with each other and their U.S. counterparts. The Japanese company NEC. for example, works closely on projects with EDS. while Fujitsu does millions of dollars of business with U.S. telecommunications stalwart MCI, which has a major facility in Richardson.

Although most Japanese plants in the U.S. employ mainly Americans, the facilities are constantly being toured by visiting senior executives from Japan (especially now that American Airlines offers a direct Tokyo-D/FW flight). Without question, each new operation that opens in the Metroplex adds to the concentration of Japanese interests in this area.

To the casual observer, the migration of Japanese companies and managers into Dallas/Fort Worth might seem helter-skelter. But savvy internationalists speak of a Grand Design behind all the Japanese do. Big Japanese banks and corporations, tied together in massive consortiums (zaibatsu), still cooperate much more closely than do American companies-or the British or Dutch, for that matter. In his acclaimed book Trading Places: How We Allowed Japan to Take the Lead, former U.S. Commerce Department official Clyde Prestowitz argues that the Japanese invest in America as part of their farsighted global competitiveness strategy. He details how Japan is building a separate economy in the U.S., one that is “characterized by a young, non-union work force, generous subsidization by local and state governments. ,. and use of the most modern plants and equipment, financed at very low rates by Japanese banks and state industrial revenue bonds. Thus, this new Japan-U.S. economy will have a potential tremendous competitive advantage over the older U.S. economy.”

Crow’s Don Williams, whose broad international background includes time in Japan and Asia, says, “Japanese companies are on a strategic track, but it’s not always so evident to outsiders. They have a global strategy, with geographic patterns, with world money markets playing a big role. They weave a network of relations. Everything leads to something else.”

The Japanese, then, gradually spin a web over a metropolitan area, but it’s often too subtle and intricate for outsiders to trace. And “outsiders,” or gaijin. we are becoming, in our own country. We are inviting the Japanese in. we are helping them build a new economy, but eventually-some warn-we will be frozen out.

Like it or not, we are part of the Japanese long-range plans-but how long-range? Ask Shuichi Takenaka. Dallas-based representative of the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan. The Perot Group recently commissioned Takenaka to prepare an extensive analysis of the Metroplex market, to be sent to major Japanese companies. Highlighted in the report, the size of a large telephone book, is the new Alliance Airport in northeast Tar-rant County. The Perot Group, which donated the land for Alliance, is plunging millions of dollars into new development projects around the airport. Crucial to the success of this venture is getting foreign as well as domestic companies committed as tenants.

Takenaka recently sent a more objective report-not sponsored by any American company-to some 1.000 companies in Japan, summing up his views of our economic health.

“It would be a mistake to conclude that the prosperity of Texas has come to an end with the fall in oil prices and the problems in the real estate market.” On the contrary, Takenaka wrote, Texas is in a period of transition during which our attempts to diversify beyond oil and real estate are “crystallizing into tangible systems and concepts.” The report also lauded the “tremendous opportunities’* lent us by our human resources and reminded prospective investors of our burgeoning high-tech industries-“especially in electronics, communications, and new-generation computers in Dallas, as well as in aerospace and robotics in Fort Worth.”

Takenaka offered his opinion that the Texas economy finally hit rock-bottom in the summer of ’87 and is now rising again. But his report did not exactly urge his fellow Japanese to rush into the Dallas real estate market: Takenaka estimated that the existing vacant office space here will take at least five years to be filled.

Five years! That assessment, shared by many local real estate people, explains why the Japanese feel they can wait before investing heavily in buildings here. Prices are not likely to surge in the near future. ’They don’t like the risk of the tenant base right now,” says Jim McLennan of Leventhal. “They don’t like the vacancy rates-30 percent-they are seeing.”

But the Japanese will be buying, however selectively. If they follow the formula they have established in cities like New York. L.A., and Chicago, they will first snatch up some downtown trophy buildings here. They are already involved in one-Texas Commerce Tower-and the list is limited. “In the category that the Japanese are interested in, Class A, space is not very plentiful,” notes Chuck Klepfer, senior vice president of Equitable Real Estate in Dallas. “A tenant looking for, say, 300,000 square feet of contiguous space in a building can’t find it.”

The Japanese have given all indications that they will not pay the outrageous prices they coughed up for such landmark properties as Fifth Avenue’s Tiffany Building, Rockefeller Center’s Exxon Building, or L. A.’s AT&T Tower. “They’re getting 3 percent to 5 percent yields on those properties, at the very best,” says Bud Weinstein, an SMU economist. “Most major U.S. institutional investors won’t accept less than 7 to 9 percent.”

The Japanese purchase of glamorous towers on the coasts fits into a worldwide global strategy, but the new owners admit they paid too much. Japanese executives blame the blunders on inexperience and ignorance, and they won’t make the same mistakes in Dallas. When Rosewood properties recently started shopping around a 50 percent stake in its Crescent complex, Japanese investors reportedly expressed great interest but complained that the price was too high.

But most other properties in Dallas are dirt cheap right now. The Japanese have the money to make offers. So what are they waiting for?

“They can afford to wail for an upward slope in the economy,” says attorney Robert Rendell of Johnson & Gibbs. “I mean a steady upward slope. They’ve been making selective investments, sticking a pole in the mud, waiting till they feel solid ground.”

The Japanese say they’ve developed an all-important intuitive feel about Honolulu, L.A., San Francisco, and even about New York. But here in Texas, they don’t trust their own instincts yet. If they’re wary, it’s because the few Japanese who have dared to test our inviting waters have found them to be treacherous. The most notable example is Sanwa Bank, which got in over its head when it put up the letter of credit for Cityplace, the proposed twin-tower behemoth that would serve as the corporate headquarters for the Southland Corporation. By the time construction on the East Tower was completed, the Dallas market had gone bust and Southland had retrenched after a leveraged buyout. Sanwa bought into Cityplace for long-term reasons, and may someday congratulate itself for foresight. Nevertheless, the sho-guns back in Tokyo typically rage when their people in the field misread a marker and mistime an investment.

The Japanese supposedly steer clear of distressed properties. However, Craig Hall, the Dallas-based syndicator who has been in the midst of restructuring, sold Judiciary Center in Washington, D.C. to Japanese interests. Andy Rooney, on one of his “60 Minutes” segments, pointed out the irony: our federal government, already in hock to the Japanese, is paying them millions of dollars a year for office space in our nation’s capital.

Another indication that the Japanese are not above bargain-hunting: Nissei Realty Inc. is participating in a new $1 billion investment fund set up by Trammell Crow to acquire commercial properties. The fund is similar to the “opportunity” or “vulture” fund that Crow created in 1987, concentrating on distressed properties.

The Japanese, especially the institutional investors like Nippon Life, are not by nature vultures, insists Bob Mullins. executive vice president of Dallas-based Lehndorff-Pacific Inc., which participates in real estate purchases with international investors. “They look for healthy, solid real estate. They are willing to pay the price up front, but they do not like to have to subsidize the property after that.” Although the Japanese are unlikely to be interested in many of the S&L properties being auctioned off by the government, some might buy the proposed zero-coupon bailout bonds, as long as they are guaranteed and mature in thirty years.

To some jumpy Japan watchers, the purchase of bonds is even more threatening to America than a property buy; indirect investments like stocks or bonds or Treasury bills can move markets. As columnist Richard Alm recently reminded readers of The Dallas Morning News: “The collapse of Continental Bank of Illinois in 1984 came about not because of faulty energy loans, but because Japanese money abruptly yanked funds out of the bank.” A similar process, Alm added, led to the stock market crash of October 1987.

But the Japanese are wary of our Financial institutions, too. Japanese interests considered buying FirstRepublic, then MCorp. They just couldn’t bring themselves to do it. “A company’s reputation, its name, means everything to the Japanese,” says attorney Rendell. The banking and S&L mess will continue to worry Japanese investors. ’The U.S. needs to stabilize its financial industry,” says Takashi “Ted”’ Noto of Tokai Bank. “It’s inevitable that a revamping will have to take place-S&Ls, branch banking, a lot of other aspects must be looked at. The public sector must step in.”

But direct investment, being tangible, is more threatening to most Americans. And we have reason to feel threatened. In his recent writings, social critic David Halberstam has been warning Americans that history is about to repeat itself: first Japan sneaked up on America by learning all about our electronics and automotive industries, only to run us over with their exports when the yen was low. Now that the yen is high, Japan is again sneaking up on us, this time learning all about acquiring our assets.

However, Robert Rendell cautions against blaming the Japanese for our dilemma. “If they master our marketplace, it’s because they work a lot harder to learn about us than we do to learn about them.” This year 20,000 Japanese students attend U.S. universities, versus just 1,800 American students currently studying in Japan.

“We understand your way of thinking” Ju-nichi Kogo of Mitsui Fudosan real estate told a group of American businessmen. “We’ve studied your language, we’ve watched your movies, we play your national sport. Such comprehension is very important.”

Are we in danger of being caught napping-again? Says former mayor and president of the Cullum Companies. Jack Evans: “The Japanese caught us by surprise in automotives simply because we weren’t paying attention. Let’s hope this time, in real estate, we’re ready to give them some good competition. It’ll be good for everybody.”

It may be too late. The giant Japanese construction companies like Kajima, which has built three office buildings in Oak Lawn. have been cozying up to Dallas developers for years in joint projects-watching, listening, learning. Soon they will move in as developers themselves. Their ace in the hole is the tremendous backing they receive from Japanese banks and other financial sources. Most Dallas developers, by contrast-including the titans like Crow-are stretched to their financial limits.

Of course, the Crow people are no fools. “I’m aware that they’re interested in becoming developers here,” Crow managing partner Don Williams says. “In a way, we’re training our future competition,”

Dallas’s local monument to Japanese dominance in the real estate market may turn out to be their first downtown “trophy”: Texas Commerce Tower. The fifty-five-story building, completed by Crow in 1987, is a joint venture between two massive insurance con-glomerates, Japan’s Nippon Life and Equitable Life, which has been cultivating a relationship with the Japanese company since the Sixties, bringing hundreds of eager interns aboard, and Trammell Crow Companies. Now, the relationship has borne fruit. “Nippon Life is an institutional investor, like us,” notes Equitable’s Chuck Klepfer. “So they operate extremely slowly, carefully. We came to them with this property, but instead of trying to unload it like a broker, we come to them as partners.”

Equitable and Crow love having rich Japanese sweethearts, but both American companies know that triangles don’t last forever. Equitable will likely be jilted first, then Crow. Nippon Life, learning to go it alone, calls itself a “sleeping partner” in the Texas Commerce Tower project, but definitely keeps one eye open.

“Our dream,” says Takahide Moribe, manager of the domestic real estate division for Nippon Life, “is to do everything ourselves.”

UNTIL THE JAPANESE CAN FULFILL their American dream, they’ll need our help-and we’re falling over ourselves to provide it. Bruce Brownlee, a broker with The Staubach Company, points to a stack of papers two feet high on his desk. “They’re proposals from brokers. They say. ’i’ve got a great property here. Get me a Japanese equity partner.” Ninety percent of the time, I’ve got to respond. Thank you. but I can’t represent you.’ They’ve got good-looking, low-priced property, and they just can’t understand why the Japanese wouldn’t want it. It’s because the yields aren’t there. There are no guarantees the property will appreciate.”

And it’s not just white elephants from the boom days that are difficult to push. “Lots of people want to sell raw land,” says Brown-lee, “but the Japanese won’t buy it unless they absolutely trust you. They’re tempted. Land potentially offers a much greater yield and return than buildings, but it’s much more difficult to understand than an income-producing property.”

In Japan, land is precious. Much of it is internally tied up in inefficient farms protected by tariffs and other trade barriers, as well as by laws discouraging sale. The Japanese, in fact, are loathe to sell any kind of property. Explains a Cushman & Wakefield analyst: “In a culture where honor and “saving face’ are deeply inculcated, the mere belief that one’s peers are going to conclude-whether correctly or not-that business problems are necessitating the sale of property is enough to dissuade most individuals from taking such action.”

The Japanese are buyers, not sellers. But when buying in an alien country, trust is essential. That’s why familiar faces like Brownlee, who was reared in Japan, are treasured by the Japanese here today. Loathe to do business with people they do not know. Japanese tend to be suspicious, especially of American lawyers and brokers, many of whom seem to be single-minded in purpose: collect fees as quickly as possible. Paying money to foreign middlemen goes against the Japanese nature, but more and more they are learning they have no choice.

If our buildings are for sale, and our land is for sale, so are our companies and our technology. Dallas, as a corporate headquarters city, is a great place to shop for all sorts of companies, and the Japanese have their wallets out. The rapid appreciation of the yen against the dollar has squeezed Japanese profits obtained from exports. With collective cash reserves of $60 billion and unlimited borrowing power, Japanese conglomerates are coming to call on local companies. “If they see a merger that makes sense, they won’t hesitate to make an offer,” says Harden Wiedemann, managing director of Bristol International.

And the Japanese make good owners. They never attempt hostile takeovers, they pay well for companies, they don’t break them up, and they leave management intact. They go out of their way to try to earn acceptance in the community, giving millions to good causes.

So what have we got to worry about?

Plenty, says John Bryant. Congress’s most prominent “trade hawk.” The East Dallas Democrat fears that we are selling away our future. “We need to update the old saying, ’What you don’t know won’t hurt you,’’’ Bryant says. “Today, what we don’t know could kill us. Knowledge is power, and the U.S. is pretty ignorant.”

Bryant has run into vehement Republican opposition in his attempts to force greater disclosure by foreign investors. He’s also created quite a stir by demanding that foreign countries be prohibited from sharing in research stemming from the proposed super collider unless they agree to foot their fair share of the bill.

What rankles Bryant most is the selling off of American assets at fire-sale prices. “I’m not saying we should deter foreign investments,” he insists. “I’m saying we should know about it. Every other country in the world tracks it better than the U.S. Japan not only effectively stymies foreign investors and companies by tangling them in red tape, it keeps tabs on every tiny transaction they make. By contrast, current information collected by our own government is ludicrously incomplete, and even Congress doesn’t have access to it.”

So far, Bryant’s protectionist tub-thumping has had a pleasant side effect: the Japanese, fearful that the U.S. will start erecting import blockades, are beginning to lower their own barriers inch by inch.

That’s just fine with Bryant, who doesn’t seem worried that his Japan-bashing might scare off investors. “The big question is: do we want anonymous foreigners financing our deficit?” he asks. “Some of my opponents say we shouldn’t be looking a gift horse in the mouth. I say we may be looking at a Trojan Horse-which we are blithely inviting in. I say beware of Greeks bearing gifts.”

Or of Japanese bearing cash.

What They’d Like To Own

Based on word from securities analysts and a host of other sources, here’s a list of likely Japanese targets in Dallas. Remember: above all, they seek technology and know-how.

●“Trophy” buildings: Trammel] Crow Center.NCNB Plaza, and Momentum Place are amongthose that “measure up” to quality standards downtown. Lincoln Plaza, The Crescent, and The Gal-leria also impress.

●Sale/lease-backs: The Japanese could findsome blue-chip properties at Las Colinas. IBM,Xerox, Exxon, GM, Kodak, et al, might be betteroff selling their real estate and freeing up their cash.

●Local real estate companies: The Japaneseneed the know-how and contacts, so don’t worry:they’ll leave management intact.

● Local investment houses: Buying into Shear-son Lehman Hutton and Goldman Sachs nationally was the start of a trend.

●Energy companies: Resource-poor Japan needsoil and gas producers. Nippon Oil, Toyo EnergyDevelopment, and others are aggressive.

●Food-processors, agribusiness: Japan’s feudalfarming system makes this a must. Seeking majorityor 100 percent ownershi

●Industrial properties: Lots of R&D needed forfast-growing Japanese high-tech firms here.

●Factories: Having a plant here means dodgingimport fees that Congress might impose.

●Computer, software firms: Dallas’s EDSteamed up with Hitachi Ltd. to buy National Advanced Systems. Look for more such integratio

●Raw land; Too complex for most as a short-terminvestment. But a young scion named SeichiroAmakasu, now based in Beverly Hills, has boughtchunks of land north of Fort Worth and just northof Dallas. He wants more. – B.A.

What They Own

“The Japanese interests here are like the advance scouts in a raiding party,” says RobertRendell of Johnson & Gibbs. Instead of bursting onto the scene, Japanese companies tiptoeinto a metro area via indirect and debt financing or via joint ventures with established localcompanies, thus learning the marketplace before committing to wholly owned projects.The smattering of Japanese investments listed below does not include the dozens of rapidlyexpanding manufacturing/research/office facilities owned by Japanese technology companies throughout the Metroplex. – B.A.

A Memo From the Writer

A journalist is supposed to be objective. But I must confess that I embarked on this assignment harboring an extreme bias: I was stridently in favor of promoting Japanese investment in Dallas. However, by the time I completed the research for this article, my attitude had swerved almost 180 degrees. Dallas, I came to realize, is in danger of losing control over its own destiny.

Ironically, I have long been an outspoken proponent of Japanese investment here. In my decade as the chief editor of Texas Business magazine, I’d often lamented the fact that our state lagged far behind the likes of Tennessee, Georgia, and Oregon in wooing Japanese money. And I was right: in fact, it wasn’t until last year that Texas finally opened an office in Tokyo to promote our state as an investment vehicle-after thirty-eight other states had beaten us to the punch. Our cities, so prosperous, had never really cared up till now; Dallas, in particular, has traditionally resisted Japanese investment. Who needed it?

But today our desire for self-determination has weakened, and pressure from the Japanese is building up because of their need to invest billions in new and freed-up cash. As a result, Dallas has gone from one ludicrous extreme to the other. “Suddenly, this town is wide open to Japanese investment,” says Scott Eubanks, executive vice president and chief operating officer of Dallas Partnership, which spearheaded the statewide private-sector funding drive for the new state office. “Let’s face it. It’s because of need. People here need to make payments on buildings.”

Suddenly delegations of prominent Dal-lasites are visiting Tokyo corporations, outbidding hundreds of competing U.S. cities for new plant relocations by offering incredible incentives and concessions (thereby inadvertently offering the Japanese competitive advantages over our own companies). Armies of real estate brokers are pitching prime property to the Japanese at unheard-of prices. And Dallas families are trying to sell companies that have been nurtured locally for generations.

Now. there’s nothing wrong with allowing, or even promoting, Japanese investment in the Metroplex. But instead of a steady, manageable flow over the course of years, we are about to witness a flood. Already, multimillion-dollar transactions are taking place, but so quietly that the public is unaware of them. Our own banks are too weak now to manage the incoming funds, and our state and city governments are woefully unprepared to monitor them.

I spent more than six solid weeks researching this story. But any information contained about specific Japanese investments here (see chart, above) comes from tapping unofficial sources, culling obscure mentions of transactions in the business sections of the newspapers, and following up on rumors. The dozens of interviews I conducted, with Japanese executives and the Dallasites who do business with them, yielded virtually no specifics. 1 wasted a week trying to wrangle information from the dozen or so federal agencies that “oversee” foreign investment in the U.S.; their statistics are overlapping, outdated, and grossly misleading.

The deeper I delved, the more I realized how ignorant we are about Japanese investment.

The Japanese, with business and government working together, know exactly whatthey’re doing. Dallas, politically disorganized and economically desperate, is playingright into their hands. – B.A.

But Do They Like It Here?

The answer varies from individual to individual. Contrary to stereotype, all Japanese do not think alike.

Many Japanese men find Dallas, and the U.S. in general, insufferably boring. “There is nothing to do after work except go home,” complains one executive who is not used to spending time with his wife and kids. In Tokyo, it is part of the corporate culture for salarymen-as white-collar businessmen are called-to spend late hours with colleagues in high-class geisha and hostess bars, classy havens where pretty young women, fully clothed, are paid to act sweet, courtesy of the salarymen’s generous expense accounts. Sitting in groups, the men informally discuss business, among other things.

But other Japanese men find Dallas absolutely liberating. “I can go home while it’s still light and spend time with my wife and kids,” raves one. “In Japan, the salaryman leads a zombie existence. You never leave work, and after a while you just go through the motions.”

Having Saturday off is strange for Japanese men, many of whom work six-day weeks back home. Many take advantage of the long weekends by taking their families boating and water-skiing-activities much less common, and much more expensive, in Japan. Horseback lessons for the kids are popular here, too. Sometimes a family will fly to San Antonio or New Orleans for the weekend.

Many Japanese executives belong to the Dallas Japanese Association, with 1,500 members (counting families and associates). All meetings are conducted in Toru Hori, a vice president at Memory Tech in Piano, and his family enjoy outdoor activities. He is shown with his wife, Keiko, and sons Daisuke (left) and Keisuke.

Japanese. The association helps arrange social activities for wives, few of whom are employed outside the home. Highly popular for men is a golf club that books courses throughout the Metroplex on weekends.

Also making the Japanese feel at home are the fifteen or so Japanese restaurants dotting the Metroplex. The consensus seems to be that Mr. Sushi serves the best raw fish in town, but for entertaining among themselves, the Japanese like Royal Tokyo. In its private tatami rooms, Japanese businessmen can sake-and-dine clients visiting from Tokyo, sitting on the floor and ordering from special menus.

The Japanese find several things about American life unsettling, including the chivalry shown women here, the astounding crime rate (in Tokyo, there are 1.8 robberies per 100,000 people, versus 205.4 per 100,000 in the U.S.), and the ubiquitous lawyers who worm their way into every aspect of American life.

The Japanese are also bewildered by the relatively extravagant standard of living enjoyed by American executives. In Japan, offices are tiny, and even the boardrooms of the richest corporations are plain-vanilla linoleum. A $100,000 salary for a senior manager, modest here, would be considered astronomical in Japan. As an informal rule of thumb, the Japanese CEO makes no more than ten times what his highest paid hourly worker earns; in the U.S., it can be one hundred times.

But is America the future after all? Whenthe Japanese here talk among themselves.they grumble about the shin-jinrui back inJapan, the “new breed” of those undertwenty-five who spend money likeAmerican yuppies and actually take all thevacation time their bosses offer. Theseyoung people travel the world, arrogantabout their spending power. They have become, their elders fear, the new “uglyAmericans.” -B.A.