CRAMMED INTO THE BACK OF A JEEP. RACING down the dark but still crowded streets of oldest Cairo at one in the morning, the four Dallasites started casting the movie. After all. it seemed as if they were in the midst of one. It was July in Egypt, the hottest part of what had to be the hottest summer anywhere. They had been sleeping little, eating nothing but grilled lamb, and drinking gin-and-tonics, second-guessing every statement, every maneuver. Their emotions whirled like the spinning dervish they had seen that night at the El Ghouri Palace. They thought they had won the grand prize, Ramses the Great. But if the past week had taught them anything, it was that appearances could be deceiving.

Exhausted but exhilarated, they roared with laughter as their driver careened through the back streets of the ancient Egyptian city. Cher would portray Eliza Solender. Martin Sheen would play Andy Stern, Fred MacMurray would be James Brooks, and Michael Douglas would be Walter Davis.

Okay, Raiders of the Lost Ark has already been made. There were no snake pits or scheming Nazis on this mission to the desert. But the rest of it was there, if in a more genteel fashion. Two equally determined factions fighting an international battle over priceless ancient artifacts from the tomb of the great Pharaoh Ramses II. A clash of wildly different cultures. A man named-no kidding- Humphrey Bogart. Desert heat, sizzling FAX lines, camel rides, snooping reporters, heated negotiations, political pressure, millions of dollars, and even a little Marion Ravenswood sex appeal, thanks to the highly impractical, bright silk cocktail dresses the thirty-seven-year-old Solender had brought from Dallas. (At one point an Egyptian man offered the group fifty camels for Solender. They turned it down. “We were holding out for more,” Stern says.)

In the words of one Cairo newspaper reporter, the Ramses affair had as many layers of intrigue “as mummy’s wrappings.” And it all started because a small, little-known Dallas museum decided to go for the big time by pursuing an exhibit that was guaranteed to pack in the crowds. Call it the Pharaoh phenomenon. Americans love (heir mummies.

DALLAS’S QUEST FOR RAMSES THE GREAT BEGAN IN 1986, WHEN Andy Stern got a call from a friend named Bill McKenzie, then president of the Dallas Museum of Natural History Association. They had met when Stern was staff assistant to President Ford in the mid-Seventies and McKenzie was Republican Party county chairman. McKenzie was looking for some new blood to inject life into an institution that at times seemed embalmed, and he thought that Stern, chairman of Sunwest Communications Inc., a public relations and sports marketing firm, would be just the man to help.

Founded in 1935 and opened in ’36 for the Texas Centennial, the Dallas Museum of Natural History was a quiet Fair Park institution with a city budget of $1 million, twenty staff members, a tiny membership of 350, and an architecturally classic building, its Texas limestone walls embedded with fossils from the Cretaceous period. The board was dominated by factions we’ll call the hunters (out-doorsy types), the academics (ornithology and paleontology buffs), and the civics (the do-gooders). The board met twice a year, and the museum never seemed to go anywhere.

Over the years, despite the fact that the museum attracted limited donations, it had built impressive collections of regional birds, the Crane Collection of fossils, and the Kline Collection of Mammals of Africa and Asia. The museum’s Mudge Library is considered one of the ten best ornithological libraries in the country. And the museum scored a coup when it mounted a largely intact skeleton of a mosasaur that had been found by a family sailing on the east shore of Lake Ray Hubbard in 1979.

But attendance figures and a survey commissioned by the museum’s forty-two-member board showed that few except school groups ever visited the museum. One reason: there was rarely anything new to see. Though the Earth Science Hall-featuring the Dallas mammoth and the mosasaur-had been installed in May 1987. little else changed. The museum’s basement is stuffed with material, but the building is too small to accommodate more exhibits. And let’s face it: fossils are a hard sell.

“We didn’t have a negative profile,” says Eliza Solender. a principal with a commercial real estate firm who joined the board as a fundraiser three years ago. “’We had no profile. We had a museum we liked but nobody knew about.”

McKenzie was determined to change that. In 1986 the museum lost Louis Gorr. its director of seven years, when he decided to move to a museum in Delaware. With interim director Richard Fullington in charge of managing the day-to-day affairs of the museum, McKenzie, who had been president since 1982, began to pull in new, energetic people. Most, like Solender, didn’t know a fossil from a football. “I hadn’t been in that place since I was a Campfire girl,” Solender says. But McKenzie attracted new people like Andy Stern by pressing home the “quality of life” issue, stressing the class that good museums bring to a city.

For a year and a half the museum board, various subcommittees, and community leaders met almost weekly to define the museum’s mission and to develop a strategy to attract more visitors. Once-passive board meetings now were packed hotbeds of debate. After all the discussion was boiled down, they came up with two proposals. First, they decided to “privatize” the institution by 1992, following the path taken by the board of the Dallas Museum of Art in the Seventies. Privatization meant that the museum would occupy a city building, but the museum membership would provide the budget and operate the institution.

“In the great majority of cities,” says James Brooks, now president of the DMNH board, “cultural institutions that survive will be private.” It’s a matter of money. Shrinking tax bases mean municipal budget cuts. And paintings, not garbage trucks, are the first to go. Privatization would mean protection from the whims of city government.

To exist apart from the city’s largess, the museum needed more space to attract more visitors. A new wing would double the museum’s size and could be financed by a $15 million bond election. But in order to pass a bond election, the public had to know the Museum of Natural History existed.

So they proposed, again, to follow the DMA’s lead. In 1978, Harry Parker, then-director of the DMA, had decided he would get the museum a new building. The DMA mounted a traveling exhibit called Pompeii. with hundreds of artifacts from the Italian city buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. The crowds flocked, and in November 1979. when the DMA proposed financing a new building with a $25 million bond election, the public responded enthusiastically, The result is one of the finest museums in the country, enriched by a thriving membership and a healthy sponsorship program. The DMNH planners could also look back a few years earlier to the biggest museum blockbuster of recent time: the 1976-79 American tour of precious artifacts from the tomb of a little-known Pharaoh named Tutankhamen-King Tut.

The DMNH needed a Pompeii, a King Tut-something that would ignite the imaginations of people from the Oklahoma border to the Panhandle to the Hill Country. It had to be something spectacular, a block- buster that would bring in as many as a half-million visitors. But blockbusters aren’t easy to find. For example, the Georgia O’Keeffe exhibit at the DMA, while successful, still brought in only about 200.000 people. They needed a traveling exhibit that was not only beautiful, but scientific; not only extensive, but somehow special, unprecedented.

As they were developing their plans, the DMNH got a little nudge from a neighbor. In August 1987, Science Place I. which occupies the old DMA building at Fair Park, opened its Robot Dinosaur exhibit, a show of fourteen prehistoric creatures that moved and bellowed. The Science Place had been going through the same reorganization process as the DMNH, but was several years ahead,

“The Science Place blew us out of the water overnight,” says Walter Davis, the DMNH’s assistant director of long-range planning. “We were angry. We had just opened the Earth Sciences exhibit, which had the thirty-foot mosasaur, a local species, the real thing.” Unfortunately, the mosasaur didn’t shake its head or snort.

The DMNH board had talked about getting the dinosaur exhibit, but had nowhere to put it, while the Science Place had a virtually empty building. But the main problem was the board waffled. “We sat around and talked about it and the Science Place got it.” says Stern. During 1987, as they watched visitors pour into the Science Place, the ten-member executive committee meetings got louder and more aggressive as the frustrated group struggled to find that one show that would catapult them into Dallas’s consciousness as the rubber dinosaurs had the Science Place.

Then W. Humphrey Bogart stepped into the picture. In December of 1987 Bogart, president of Fidelity Investments Southwest, a Boston-based mutual fund company with offices in Las Colinas. called Davis at the museum. Had Davis heard about a traveling exhibit, Ramses the Great, that was drawing record crowds at the Denver Museum of Natural History? Edward C. Johnson, the chairman of the board of Fidelity, was on the Boston Museum of Science’s board, and the Fidelity Foundation had donated $300,000 to underwrite the exhibit in Boston on its next stop. During a visit to Dallas, Johnson mentioned Ramses to Bogart and Doug Reed, director of corporate communications, and suggested the exhibit “might lift the spirits of Dallas,” Bogart says. Fidelity could underwrite a portion of the funds needed.

Fidelity’s motives weren’t completely altruistic, Bogart admits. The company, which had been in Dallas only five years. would not only enhance its community image, but get a chance to build name recognition with (he right crowd; people likely to visit a museum to see Egyptian treasures are also likely to buy mutual funds.

Davis contacted Bedair Elgam-rawy. the consul general for Egypt based in Houston. The exhibit had been in the United States since November 1986; as it happened, the Egyptians were looking for a final venue in the Southwest, possibly Texas. The exhibit was scheduled to visit Charlotte. North Carolina, after Boston. It could open in Dallas March 1; that was cutting it close, but Davis thought the museum had enough time to prepare. Within a week, he had a sample contract.

On January 7, the day of the worst ice storm of the winter, Davis met with Bogart and Reed and talked about Fidelity’s underwriting Ramses. On January 12, Davis presented the idea to the museum board’s executive committee and recommended that they consider it.

People on the DMNH board called their counterparts in San Antonio and Houston to find out if there was any interest in those cities. The interest was there, they learned, but no one was actively working on it. They also discovered that they weren’t the first in Dallas to talk to the Egyptians about Ramses. Richard Coyne, director of the Science Place, had flown to the exhibit’s opening in Memphis, but had made no effort to bring it to Dallas; his plate was full with an exhibit on China, and later, the dinosaurs. And Parker at the DMA had been contacted and expressed little interest; he was doing the Wendy and Emery Reves collection, among other things.

“They just dropped it.” says Stern. Of course, all this was baffling to the Egyptians, whose cultural affairs are under one national umbrella organization. They didn’t understand that Dallas could have a number of museums, and that each was an independent entity operating without the others’ knowledge. “We looked terribly indecisive as a city,” Stern says.

On January 27, while the board mulled and debated, Davis and Bill McLaughlin, then-manager of Fair Park, flew to Denver to see the exhibit. It was a snowy day, but lines snaked inside the museum as people waited to get in to see Ramses. They raced through the exhibit in thirty minutes and flew back. “But I could tell it was huge,” Davis says. “I was impressed by their installation.” (When Ramses closed in Denver, 908.000 people had seen the exhibit.)

Back in Dallas, on February 9, McKenzie appointed a Ramses steering committee with James Brooks, head of the Institute for the Study of Earth and Man at Southern Methodist University, as chairman. The committee, which included Mary Ellen Degnan from Friends of Fair Park and Judy Tycher of the Park and Recreation Board, poured over the contract used by the Boston museum. The Egyptians wanted a front-end minimum of $500,000 for the exhibit, plus all profits from the gate, souvenir sales, and catalogue sales.

This, from a museum association that had $23,000 in its operating account.

One event that gave them courage was the January 30 visit of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to Dallas. He and Mayor Annette Strauss hit it off. And by February, they had the money; the Fidelity Foundation gave them $150,000, and the Meadows Foundation came up with $350,000. They had the space-a facility, actually a mini-museum, would be constructed within the Automo-bile Building at Fair Park. At a special meeting of the museum’s full board on March 8. the board unanimously approved a proposal to bring Ramses to Dallas. Brooks, scheduled to visit Egypt and Yemen for SMU, was designated to sign a protocol letter with the Egyptians, a precursor to a more detailed contract.

A lot of deep breaths were taken around the board room that day, Could they pull it off? “We were scared,” says Eliza Solender. They were about to enter the international art world, where they would discover not only intrigue in high places, but dangerous rivals from their own back yard.

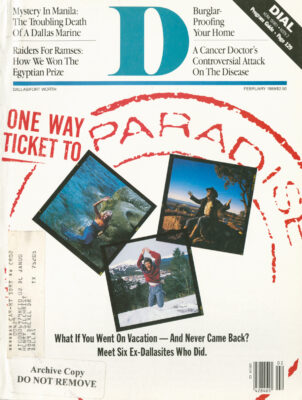

FOR A NATURAL HISTORY museum looking to make its mark. Ramses the Great is an ideal exhibit. The largest single collection of artifacts ever to leave Egypt, the show features seventy-two antiquities from the reign of the last great Pharaoh, Ramses II. who reigned from 1290-24 B.C. Visitors see not only the spectacular-the massive gold earrings, exquisite alabaster pots. painted wood coffins that protected mummies, and the Colossus, a twenty-seven-foot-tall statue of Ramses-but everyday objects: a scribal palette, a builder’s right angle, a cubit rod and plumb level, a mirror of bronze, a wig comb, a bronze razor, a game, a standing lamp.

Though most American museums have mounted Ramses as an art exhibit, the show lends itself perfectly to a science interpretation. And that’s what the DMNH planned to do: construct educational displays, bring in Egyptian artisans, create its own version of The Souk, an ancient open-air marketplace, bazaar, and artists* haven, and present lectures by Egyptologists.

From a 20th-century marketing perspective, Ramses II, of all the Pharaohs in Egypt’s Golden Age. offers some interesting possibilities, says Stern. Thought by many to be the Pharaoh of the Exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt, and thus Moses’s adoptive brother, he appeals to Jewish and Christian viewers. The minority community is fascinated because some scholars believe that Ramses II was Nubian-a black African. (Egyptian officials tiptoe around the question, but the scholarly evidence seems inconclusive.)

As it all sank in, the DMNH board got more and more excited. In early March Brooks left for Yemen, where he was met by Dr. Fred Wendorf. the senior archaeologist at SMU working in Middle Eastern prehistory. Wendorf had trained a number of Egyp-tian graduate students at SMU. many of whom now held positions with the Egyptian government, and warned Brooks that a shake-up was coming in the Ministry of Culture and its arm. the Egyptian Antiquities Organization. Dallas would be in a better position if a protocol letter was signed before the changes occurred.

Egypt’s ancient culture is its livelihood. Tourism and the export of traveling exhibits provide a large portion of the country’s income, and therefore, the Ministry of Culture and the EAO are powerful organizations, Brooks says. But the chain of command can be confusing, especially to outsiders.

Brooks spent four days in Cairo negotiating with Ibrahim El Nawawi. the acting director general of the EAO. “We were getting a lot of support from our friends in Cairo,” Brooks says. For years, SMU has participated in research in Egypt, and a number of Egyptian earth scientists have trained at the school. After a frantic exchange of phone calls and telexes between Cairo and Dallas. Brooks signed a letter of protocol on March 15. Mohamed Mohsen, the director general of the Egyptian Museum and a Soviet-trained official who spoke no English, signed for El Nawawi. The short letter agreed that the Dallas Museum of Natural History Association had a “prior position,” contingent on being able to provide the requisite financial guarantees by May.

Brooks returned home to much exultation, expecting that the details of the contract would be hammered out. For a month they heard little because April was Ramadan, a month of fasting for Moslems. The Egyptian government was shut down.

But in mid-April the deal began to unravel in such minute threads that no one saw it coming at first. A friend from the Denver museum called Davis to say that a delegation from San Antonio had flown up to see the exhibit on its last day, and one of them had told him Dallas was no longer interested. Alarmed, Davis flew to Denver and in the museum office saw what has come to be called “the smoking pinata”-gifts from the San Antonio delegation.

Bill McKenzie spoke with San Antonio Mayor Henry Cisneros, who told him that San Antonio had made no concerted effort to land Ramses. McKenzie told Cisneros what they had done on the exhibit so far. and he says that Cisneros agreed to take the exhibit after it showed in Dallas. But while Cisneros was issuing denials, San Antonio continued to aggressively pursue the exhibit with the encouragement of Cisneros. And early on, he or someone in the San Antonio museum organization must have known it was impossible for both cities to have it.

Meanwhile, the Dallas group learned that El Nawawi-the man who had negotiated the letter of protocol-was out, and Abd El Halim Nour-El-din was the new director general of the EAO. During the last week in April. Davis got an agitated call from Zahi Hawass, consultant to the Ministry of Culture on Archaeology, a post roughly similar to being director of Yellowstone National Park. He had met with Deborah Alves, a representative for San Antonio. They were interested. Hawass, who knew of the DMNH’s interest, insisted that Dallas had to get to Cairo to sign an agreement. He was unaware that SMU’s Brooks had already signed a protocol letter.

A few days later, Brooks called Hawass in Cairo and explained that he had already been to Egypt and signed the letter, but Hawass continued to insist that they come back. Brooks also talked to Nour-El-din in Boston about the agreement; feeling that all was well, he decided not to go to Egypt.

On May 10, Brooks received a telex from Nour-El-din. “They wanted more money,” says Brooks-$100,000 more. The executive committee met and decided the request was reasonable because they were asking for six months, a month longer than the other cities.

The bomb dropped on May 19, when a San Antonio newspaper ran a story headlined “Dallas Leads Ramses Race,” detailing San Antonio’s determination to snare the Ramses exhibit.

“We panicked,” says Stern. “We couldn’t believe it.” They thought they had a done deal and discovered themselves in a horse race; something had gone wrong.

Brooks called his friends in Egypt, who assured him that details of the contract were being worked out and the American ambassador in Egypt could sign it to save them a trip to Cairo. But around the first of June, a friend called back with strange news. A group from San Antonio, including Alves and former ambassador to Mexico Bob Krueger, was in Cairo to sign a contract “with a check for $1 million.” The San Antonio press made it official, quoting Nour-El-din: San Antonio had it. Krueger and Alves returned in triumph, presenting each San Antonio council member with a bottle of champagne adorned with the Ramses likeness.

Alves says now that San Antonio pursued the exhibit because their Egyptian contacts repeatedly assured them that while Dallas had expressed a strong interest, the deal wasn’t final. They indicated that Dallas had not met the financial criteria. “They told us we had put together a better package,” Alves says, citing San Antonio’s promise to put together a documentary to air in Mexico and the city’s strong position as a tourist spot.

But Dallas had met its financial goals, and the DMNH group couldn’t understand what had gone wrong. “There’s no way to explain how we felt,” says Stern. Confused and frustrated, the executive committee met on June 14. Should they continue to pursue Ramses? They realized that here was an inter-city rivalry with an international dimension, that it could get messy. Could they afford to fight and win? San Antonio wasn’t really offering $1 million, but they were close: $850,000, based on paid admissions and percentages of gross revenues of audio tape rentals, gifts, and catalogues.

But the Dallas team couldn’t give up. After some number crunching, they felt they could meet the new terms. How to get back in the game? “We saw that we needed power behind us.” Solender says. Judy Tycher asked powerbroker Robert Strauss to contact the Egyptian ambassador and President Mubarak, a personal friend from Strauss’s days as a Middle East negotiator.

That same day, the executive committee went to see Mayor Annette Strauss. After chiding them for calling Cisneros directly instead of going through her office, the mayor encouraged them to go for it and agreed to arrange a meeting with the Egyptian ambassador. El Sayed Abdel Raouf El Reedy. A week later Stern, Davis, and Brooks found El Reedy “gracious and supportive.” says Brooks. They were ready to go to Cairo immediately, they told El Reedy. Brooks says they were given the impression that if they matched San Antonio’s terms. Dallas would have the exhibit, as simple as that. They went home and started packing.

ON WEDNESDAY, JUNE 29. SOLENDER, Stern, Davis, and Brooks boarded a plane for Egypt. Thirty hours later, after a stop in Frankfurt, they landed in Cairo on Thursday night and were hit by a wave of heat that made Dallas summers seem balmy in comparison. They were met by one of Brooks’s friends who had canceled his weekend in Alexandria to meet them. Bad news. “He told us it wasn’t a done deal as we had thought.” Brooks says.

At the hotel on Friday, Brooks got a call from J. Carter Brown, the executive director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Considered the premier museum director in the United States, indeed a kind of “museum diplomat,” Brown was one of the organizers of the King Tut exhibit. The call was brief and friendly, but it kicked off a round of endless worry and strategizing: what was Brown’s interest? Why was he in Cairo? They later discovered that he was putting the final touches on a deal for another exhibit called The Glory of Ancient Egypt, a fact that would become significant later.

Through a call with a friend at the State Department, Stem discovered that the “guys at the Middle East desk” were watching the internecine warfare between Dallas and San Antonio. “They think it’s hilarious.” the friend told him. Later that evening, Dick Undeland, the American cultural attaché, told them that San Antonio was still involved and moving forward. “He didn’t know how it would work out,” Stern says. Of course the embassy had to maintain appropriate diplomatic distance. They couldn’t get involved in a struggle between two American cities.

Brooks then called Larry Chalmers, president of the San Antonio Museum Association. Chalmers told him that he had great reservations about the Ramses exhibit. SAMA had barely broken ground on the new wing that would house it next April. But he told Brooks that San Antonio was also sending a delegation to Cairo; they would arrive early the next week. That news sent the Dallas Four into new paroxysms of worry and paranoia.

The next morning, after a fitful night’s sleep, the four arrived at the Minister of Culture’s office a little before eleven. They were sipping tea in an anteroom when their translator was ushered in. “You could have knocked me over with a feather,” says Brooks. It was Fekri Hassan, a former student of Brooks’s at SMU.

The five were taken into the minister’s office, where they found Minister of Culture Farouk Hosni, Nour-El-din, and Hawass. Brooks promptly launched into the usual speech about how glad Dallas was to work with the Egyptians. The minister cut him off abruptly, “We have a problem,” Hassan said. “He wants to see the letter.”

When Brooks produced the letter of protocol, the minister and four other Egyptian officials rushed to look at it, as if they had doubted its existence. Stern cast a sidelong look at Solender. “We’re dead meat,” he muttered. At that point, he realized there was no simple solution to the problem.

After much discussion. Brooks finally explained that Mohsen, the director general of the Egyptian museum, had signed the letter for the departed El Nawawi, and pressed them to sign an agreement giving the exhibit to Dallas. Hawass chose that moment to announce that the San Antonio delegation would be arriving on Monday. “Why are they coming?” the minister asked. “Who invited them? I will not receive them.”

Another official spoke up. There was another exhibit, Gold of the Pharaohs. He urged Dallas to take Gold of the Pharaohs and leave Ramses to San Antonio. But Gold was primarily an art exhibit, unsuitable for the Dallas Museum of Natural History. The official then tried the stick. If the problem could not be resolved, neither Dallas nor San Antonio would get an Egyptian exhibit.

Attending the theater of dance at the El Ghouri Palace that night, in heat that made their clothes cling to their backs, they mingled with Egyptians from the Ministry of Culture and met Brown and Jim Romano, a premier Egyptologist from the Brooklyn Museum. They and several Egyptians congratulated the Dallas delegation for snaring Ramses; the rumor was that San Antonio had agreed to take Gold of the Pharaohs. They were skeptical but hopeful that the rumors were true. Near midnight, the entire party came to a standstill, watching a “whirling dervish” spin for twenty minutes, taking clothing off and putting it on. never breaking the motion, then abruptly bowing and walking off stage.

The minister offered to take them home. Thinking he had a limousine outside, they agreed, only to discover themselves racing through the back streets of oldest Cairo in a jeep-tired, confused, casting their movie. They were strangers in a strange land. That and the fact that they had been eating nothing but grilled meat and drinking gin-and-tonics (to avoid the Egyptian version of turista), took its toll. “When you’re in a foreign country that is so different, not even with the same alphabet, you develop a siege mentality,” says Brooks. The result was wild giggling; their Egyptian driver must have wondered what was so funny at 1:30 a.m.

THROUGHOUT THE WEEK, THEY raced with news and rumors between their rooms at the hotel, which had an excellent communications system. The FAX traffic and the intercontinental phone lines between the El-Gezirah Sheraton and Dallas sizzled. (Excluding airfare, the trip cost $11,000; more than $3,000 went for FAX and phone use.) They received messages from the museum, their Dallas offices, the mayor. newspaper reporters. They often knew what was being said in the San Antonio papers, which were stepping up their coverage, as quickly as San Antonio readers. The Dallas papers didn’t pick up on the story until it was almost a fait accompli.

Sunday, they were invited to the Giza Pyramids by Hawass. They agreed that Davis and Brooks would go and talk with Hawass, while Stern and Solender stayed in Cairo and talked to reporters. Straightforward negotiations hadn’t worked; they would try a little psychology. “We wanted Zahi to think we were going to do the press.” says Stern, a consummate strategist.

That night, the Dallas delegation had dinner with Hawass and the other officials involved in the negotiations. They talked for hours until Hawass promised that if they met San Antonio’s terms. Dallas had the prior claim. “Even so, we weren’t convinced,” Solender says. They sat at a bar on the Nile and talked for hours. They would know more soon; the delegation from San Antonio was scheduled to arrive the next day. They postponed their airline reservations.

Monday was the Fourth of July, and the Dallas delegation attended the American embassy’s annual party. The night before, the U.S. Navy had shot down an Iranian airliner in the Persian Gulf, The atmosphere was tense; heavy artillery was stationed around the embassy for three blocks. The Dallas visitors had to show their passports three times. But Stern had talked to American ambassador Frank Wisner the day before and felt it was important that they touch base with him again. They were already there a day longer than they had expected: they might as well make use of it.

As they ate traditional American fare-hot dogs and Dr Pepper-the ambassador, surrounded by bodyguards, began walking away. Solender, oblivious to the guards, grabbed the ambassador by the arm as she would do at a party at home. She laughs now, but at the time, with marksmen stationed on the roofs, it wasn’t funny. They spoke to the ambassador and explained their mission further. “We just wanted to say we had talked to him about it,” Stern says. Strategy, again.

They spent the afternoon in Khan El Khalili, the oldest part of Cairo, at The Souk, an ancient bazaar crammed with booths occupied by gold- and silversmiths, rug merchants, produce sellers. That night they contemplated twenty-five different scenarios. If the Egyptians said this, they would say that. If San Antonio offered that, they would say this. Paranoia was rampant.

At 8 a.m. on Tuesday, Stern ran screaming down the hall of the hotel. The Egyptian Gazette had a story that all exhibits would now carry a price tag of $1 million. They could swing $850,000, but where would they get any more? (Brooks says the price increase had been coming for a while, but it might have been triggered by the Dallas-San Antonio dispute.)

At 2 p.m., the San Antonio delegation emerged from its meeting with the Minister of Culture. The Dallas delegation filed into the small, excruciatingly hot room. There was a problem. There was a Dallas letter and a San Antonio letter. And Mohsen was saying he didn’t remember signing the Dallas letter of protocol.

Stern pulled out newspaper clips from the San Antonio papers, showing that the rival museum had broken ground for the new wing only the day before. And Brooks pressed Mohsen. “You sat right there and signed it,” Brooks told the Egyptian. Mohsen retreated in silence.

But Nour-El-din was adamant. “How can we change our minds?” he told them. “They’ve offered us $1 million. It’s been in our press that we have signed with San Antonio.” {The Dallasites later discovered that Nour-El-din had not seen their correspondence agreeing to match San Antonio’s offer, which was not $1 million, but $850,000.)

“If we cannot work this out, no one will get it,” said Nour-EI-din, obviously concerned that his government would offend someone and cause an international incident. “The two cities should sit down and figure it out together.”

At 2:30, the Egyptians sent the Dallas delegation to a room down the hall. The San Antonio delegation was sitting at a table against one wall. They lined up on the other. Brooks and Stern explained Dallas’s position and urged San Antonio to take Gold of the Pharaohs. “For the first time, San Antonio realized that we were not claim-jumpers,” Brooks says. Chalmers and City Manager Louis Fox explained their dilemma. They had been working on the deal since November; Mayor Cisneros had told them not to come back without the exhibit. Louis Fox spoke for San Antonio.

“You can’t do a Solomon’s baby on this thing,” Fox told them. “The problem for us is that Gold of the Pharaohs won’t help our mayor. He won’t be in office. [Henry Cisneros leaves office in May 1989.] I have nothing to fall back on. It’s okay if nobody gets it.”

Meanwhile. Solender was passing notes to Stern. She realized that the rival delegations could not come to an agreement. Egypt would have to decide. Brooks called for a break, and they walked down the hall just as Fekri Hassan, their translator, walked in. They explained what was going on, and at 4:15, as the museum was closing, Hassan went into a meeting with the Egyptian officials. The Dallas and San Antonio delegations met in the hall and agreed to abide by whatever decision the Egyptians made, but the Egyptians weren’t happy about it. The two groups headed back to their hotels for a night of roller-coaster emotions. Solender thought about all the money that had been raised for Ramses-totaling $800,000 by then. (The Perot Foundation loaned $300,000.) Failure now would be a costly embarrassment.

Brooks called Mayor Strauss, who told them Robert Strauss would not call Mubarak on their behalf. Their morale sagged. It was midnight. “The ball had stopped spinning,” says Stern, the original spin doctor. “It was dead in the water.” For the third time they rescheduled their plane flights and began packing, determined to leave the next day.

But at 1:30 a.m., Stern got the ball spinning again. His partner, Margaret Nathan, called from Dallas. A San Antonio reporter had phoned. Stem promptly called him back and planted a story. The effort to get Ramses had garnered criticism from the museum community in San Antonio because of the exhibit’s cost and the need to speed up construction of the museum’s new wing. Stern told the reporter that the city had another option. They could get the U.S. premiere of Gold of the Pharaohs instead. The cost would be less and they wouldn’t have to fast-track the museum wing.

Then they called McKenzie and told him to pull out the political stops. McKenzie called U.S. Representatives Steve Bartlett, John Bryant, and Martin Frost of Dallas and asked them to phone the Egyptian ambassador and say just one thing: Egypt must make a decision. Choose Dallas or San Antonio, but decide. At 3:30, they decided to grab some sleep.

At 5:30 a.m., Mayor Strauss called Brooks. Bob Strauss had agreed after all to send a message to Mubarak. “We’re all pulling for you and we really appreciate you.” she chirped.

At 9 a. m.. Hassan came by and suggested they stay in the hotel for the day. “Something is going to happen,” he said. He was right. When the phone rang at 5 p.m., Nour-El-din was on the line. “Congratulations,” he told Brooks, “we’ve made a decision to go to Dallas.”

He should have been jumping up and down, but the most Brooks could muster was a thumbs up. Exhausted, he was afraid to celebrate until San Antonio had been told they were out. Brooks suggested they come right over and sign the agreement.

“Oh no,” Nour-El-din said. “We’ll have a joint signing ceremony tomorrow at 9:30 a.m.” They groaned and changed their plane reservations for a fourth time. (Actually, they had almost begun to look forward to visiting the Lufthansa office; at least it was air-conditioned.)

The next day, the signing ceremony turned into a two-hour negotiating session. If the other days had been steamy, this one positively percolated. As Mohsen and Brooks discussed the contract line by line, drops of sweat speckled the pages. The final agreement gave the Egyptians a guaranteed net of $850,000, plus percentages of other revenues that could total as much as $1 million.

Nour-El-din, anxious to bolt to another appointment, signed the contract on the wrong line as Mohsen, still trying to negotiate, grabbed for the contract. The Dallas delegation scooped up the papers and escaped.

Meanwhile, the San Antonio delegation and a spokesman for the National Gallery of Art were negotiating their own contracts. But to the Dallas delegation’s surprise, this was not for Gold of the Pharaohs, but for The Glory of Ancient Egypt, which San Antonio’s Chalmers had wanted all along. It would be the most comprehensive exhibit of artifacts from the period of the Pharaohs. San Antonio would be in the prestigious spot of hosting the exhibit after its debut at the National Gallery.

Brooks says they later discovered Brown had promised The Glory of Ancient Egypt to the Dallas Museum of Art-a promise negated by the contract with San Antonio. “We deeply regret that and feel we were manipulated,” Brooks says. But could another exhibit of Egyptian artifacts be successful in Dallas, following so closely on the heels of Ramses? It’s doubtful.

On their last night in Cairo, the Dallas group visited the Sound and Light Show at the Pyramids, a magnificent spectacle they reached after the cab ride of a lifetime-the driver steering onto sidewalks, going the wrong way down streets, screaming obscenities at everyone in his way. It was the wild car chase scene, a fitting end to this international scramble for ancient riches.

During the show, all four of them fell asleep.

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman