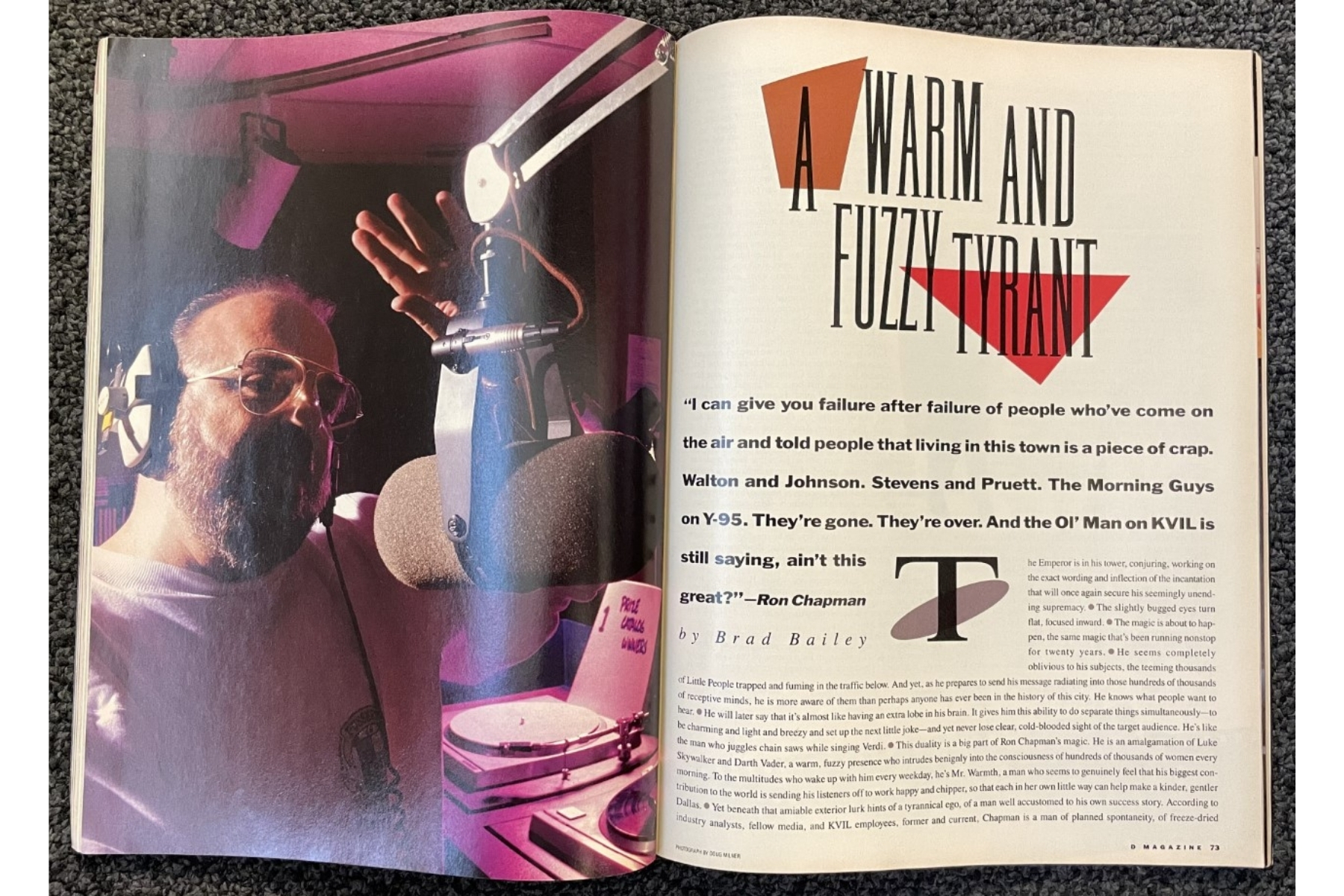

The Emperor is in his tower, conjuring, working on the exact wording and inflection of the incantation that will once again secure his seemingly unending supremacy. The slightly bugged eyes turn flat, focused inward. The magic is about to happen, the same magic that’s been running nonstop for twenty years. He seems completely oblivious to his subjects, the teeming thousands of Little People trapped and fuming in the traffic below. And yet, as he prepares to send his message radiating into those hundreds of thousands of receptive minds, he is more aware of them than perhaps anyone has ever been in the history of this city.

He knows what people want to hear. He will later say that it’s almost like having an extra lobe in his brain. It gives him this ability to do separate things simultaneously—to be charming and light and breezy and set up the next little joke-and yet never lose clear, cold-blooded sight of the target audience. He’s like the man who juggles chain saws while singing Verdi. This duality is a big part of Ron Chapman’s magic. He is an amalgamation of Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, a warm, fuzzy presence who intrudes benignly into the consciousness of hundreds of thousands of women every morning.

To the multitudes who wake up with him every weekday, he’s Mr. Warmth, a man who seems to genuinely feel that his biggest contribution to the world is sending his listeners off to work happy and chipper, so that each in her own little way can help make a kinder, gentler Dallas. Yet beneath that amiable exterior lurk hints of a tyrannical ego, of a man well accustomed to his own success story. According to industry analysts, fellow media, and KVIL employees, former and current, Chapman is a man of planned spontaneity, of freeze-dried warmth. On the mike, butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth.

But off-mike, in what employees call his “little Come to Jesus talks,” that mouth can get hot enough to melt pig iron. He is a walking contradiction, a Type A masquerading as a Type B. Or, according to Alex Burton, until his recent firing the voice of KRLD, “He’s a right-brained man who manages to sound left-brained.”

Chapman’s associates swear that he’s a perfect friend—as long as you never do anything that might make him mad. And that means don’t do anything to KVIL. When it comes to his precious radio station, the man is as fiercely protective of his listeners and his formal as a mother sow is of her litter.

But Chapman’s vaunted ego and his famed temper have only enhanced his hold on the Dallas radio market. When New York-based Infinity Broadcasting bought KVIL a couple of years ago, they paid more than $80 million, the highest amount ever paid for a stand-alone radio station in the U.S.

But they weren’t really buying the station. That’s just the wrapper. They were buying Ron Chapman—at something like a half million dollars a pound.

And now. the magic morning man takes a deep breath, raises his index finger before his eyes, and does what Ron Chapman does best:

KAY... he breathes, low and confiding, in a voice that mirrors the softest, kindest, deepest, afterglow moments of romantic love. The hand goes higher above his head:

VEE… higher now, almost pleading as it keens with the anticipation of all the wonderful, warm, cuddly, sensual things to come.

EYE... descending now, deeper into the warmth and coziness; the voice says Yes, my dearest, you are almost home, safe and warm here with me, with us…

Both hands are up now for the finale:

ELLLLLLLLL…very low and smoky-warm, like embers in the fireplace and sleeping babies in rooms with duckies on the wall, like hearth and home and cows dozing in the barn, and maybe a comforter over your legs on a winter evening…

He can do this in four letters.

Think what he can do in four hours.

Not too long ago, Ron Chapman received a postcard. On it was a headshot of some fierce new arrival on the Dallas radio scene, the latest young gun bent on a showdown with Chapman at the WBOK Corral. Next to the picture, the new kid on the block had penned, “Don’t buy a house here. Ron.”

Chapman, fifty-three, fell over laughing. But the laughter was tinged with something like pity. Chapman remembers all the other long-gone-and-forgotten ones who came gunning for him: the Mobys in the Morning, the Stevenses and Pruetts. Chapman has seen twenty years’ worth of six-month wonders come and then go.

For nearly thirteen years, with a few scattered intermissions. Chapman’s radio station has been number one in Dallas. In 1989, KVIL reigned supreme for three consecutive quarters, reaching 10.5 ratings points in the July Arbitrons, 3.1 points ahead of runner-up KSCS. Each ratings point represents a percentage of the audience market share and is said to be worth about $1.3 million in advertising revenues yearly.

“Each year, I am more and more aware of the power we have in that room,” Chapman confides. Last year, that power was demonstrated when Chapman asked listeners to trust him and send in $20 each for no specified purpose. Some 12,000 did, and KVIL donated $240,000 to charity.

“That’s reflective of some pretty strong public service.” Chapman says. “They’ll still be talking about that twenty years from now. Everywhere 1 go, the broadcasters are asking me how to do that. I tell them, you can’t do that. It won’t work for you.”

Chapman knows his audience, and he knows what they buy—comfort. “I’m talking to a thirty-year-old female. A secretary, yeah, sure, absolutely, but she won’t be for long. Because she’s gonna move up. She’s divorced, and may have a kid at home that she’s sole support for. Right away, you know two things about her: she has no time to waste, and you don’t mess with her. You treat her with respect.

“In my mind,” Chapman continues, “I used to picture Mary Tyler Moore. Then it became Jane Fonda for a while. Now, it’s someone I found out of Kim Dawson headshots. And she looks so good by the time she gets to the office, she had to be up by 5:30. I figure we have her ears, and we’re the only ones she’ll let talk to her for the first hour of the day. Ron Chapman’s the only one that talks to her that first hour, and in that hour, 1 can mold her frame of mind. I can make her feel good about the day, or I can make her feel crappy about the day, and of course, the choice is to make her feel good. That’s power. And it’s also a public service if you use it right.”

If Chapman knows just what to say on the air, he also knows what not to blurt out: no jokes that have females as the butt. No sexism, period.

Nothing to embarrass a woman who is even remotely prudish. Chapman maintains that the station turns down huge amounts of revenue from advertisers who are dying to get at his listeners: Massengill, Preparation H, etc. No dice.

But there is more to the message than merely commercialized feminism. Chapman knows how to be reassuring to women who are fighting an uphill battle day after day. Wowwwwww, Chapman warmly asserts, and Okaaaaaaay and Alllllllright and Well suuure.

Chapman and his morning cohorts—Suzy Humphries, Jody Dean, Michael Rey, et al.—are saying, in effect. Yes, my dear, the world is still a warm and safe and funny place to be, and you are on top of it with us, you know everything we do, which is a lot, and life keeps getting better.

Chapman is not just guessing at what his audience wants to hear He is downright methodical about it. According to Tony Garrett. who served as KVIL’s newsman for a couple of years during the early Seventies, Chapman is obsessed with his work. “He is single-minded, living and breathing and eating KVIL to the detriment of everything else in his life. He works on his show twelve, fourteen, sixteen hours a day. Even in a social setting, conversation revolves around radio and the show and the things that are, for other people, rather peripheral.”

Chapman says he has always had to be aggressive because back in the early days, the ratings were so low that they didn’t even show up on Arbitron. Garrett remembers eavesdropping with Chapman on conversations at the local coffee shop or the grocery store, trying to get a feel for what people were talking about. “Back then,” Chapman says, “we’d latch on to anything. It was the only way we could get a feel for the public’s impressions on what we were doing. And I’d walk a mile for an impression.”

Part of the magic of KVIL is that it is positive and upbeat, even when it’s poking fun at the news, the politicians, or the Cowboys. “Hey,” says Chapman, “most people like living here. So why should you go on the air and tell people who love living here that the town is a piece of crap? I can give you failure after failure of people who’ve come on the air in this market and tried to do that. Walton and Johnson. Stevens and Pruett. The Morning Guys on Y-95. They’re gone. They’re over. And the 01’ Man on KVIL is still saying, ain’t this great? And guess what? He’s right. I know something the others haven’t figured out.”

Warm and fuzzy was the game plan from the very beginning. Chapman had done the “Charley and Harrigan” show on KLIF during the Sixties (Chapman went by Irving Harrigan then) and had hosted “Sump’n Else,” a low-budget local version of “American Bandstand” on Channel 8. In 1969, he teamed up with local radio men Hugh Lampman and Jack Shell at the newly born KVIL. About all they had were some call letters, and not very good ones at that. But KVIL saw a huge, underserved demographic: women listeners between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four account for some 22 percent of the Dallas/Fort Worth radio market. Ron Chapman set out to claim it.

Chapman targeted that audience for several reasons, and he lists them the way he says almost everything, with unflappable confidence: ’”a) they are the purse strings; b) there are a lot of them; c) they tend to be very faithful and build an allegiance; and d) they were underserved in this market, and nobody was paying them any respect. That’s what we started doing. There are a lot of stations right now that will say, after they read this, “Oooooh, so that’s what they’re doing.’ They still don’t know it.”

Even the KVIL signal is altered to be pleasing to a woman’s “naturally more sensitive” ears. Says Chapman, “Electronically, we don’t do much, but we are very conscious of highs. You realize we don’t play the same things for a thirty-five-year-old female that you’d play on the Zoo. We play some stuff that cooks pretty good, but there are a lot of songs we won’t play at all. There’s a Stevie Wonder song where right in the middle of the song he does this loud, high-pitched scream. We edited it out. Would Stevie Wonder object if we took it out? Yeah, he would. But would he be really pissed if we never played it at all?”

The other bold stroke by the founders of KVIL was its attitude toward Dallas’s sister city, Fort Worth. Early on. Chapman realized that if he won Fort Worth, he could almost double the station’s numbers. “We decided we would keep Fort Worth, and treat her like the lady that she is. Fort Worth was the butt of all the jokes by DJs sitting in Dallas talking about people ’over in” Fort Worth. It’s a trap: if you are situated in Dallas, you look at things from the Dallas perspective, even unconsciously. You tend to say things like ‘the mayor’ when you mean Dallas and ‘the mayor of Fort Worth’ when you’re talking about them. We don’t do that here.

“This is a secret, but we take a lot of the staff to the big derrick at Six Flags and put them on top. We tell them, ‘Here’s the concept. The Right Hand of God is Dallas. The Left Hand of God is Fort Worth.” I can tell you that little secret and know the competition will pick up on it, and they’ll work on it. But they’ll never work hard enough.”

A computerized Young Chang Grand Piano is playing Gershwin via floppy disk over near the bar. On the stairwell is a wall full of pictures: Ron in the midst of a million one-dollar bills. Ron preparing to parachute out of an airplane and broadcast all the way to the ground. Ron in makeup for his role in an episode of “Police Story.” Ron’s face superimposed on the body of Michael Jackson. (“A whole lot better,” wife Nance is quick to observe, “than the other way around.”) Outside the floor-to-ceiling windows, a man-made creek meanders past a resistance pool and a hot tub on its way to the pump. “It’s what you’d get if God had money,” Nance says.

Nance (pronounced Nancy), Chapman’s wife of three years, is the centerpiece of the home tour. Blonde, voluptuous, impeccably well-mannered, and gracious, she smiles through a mouthful of sharp teeth. “Go ahead and ask me whatever you want. But it doesn’t mean that I won’t stick my heel in your throat. Mess with Ron and I might become an ape in heat and jump all over you. Other than that, I’m real comfortable.”

With that warning, we move through room after room of airy, fresh pastels, past furniture that looks as if it never gets touched, with the exception of Ron’s well-worn leather chair. Here and there, she reveals a snippet about her husband.

Chapman is a perfectionist in every way, Nance says. “He is very perfectionist about his personal things. He must know where everything is at all times. He likes certain things in certain places. He doesn’t want to look for cuff links.”

And as for keeping up with the competition, well, Chapman has a television parked in front of his toilet. Next to it is a portable telephone, complementing cellular phones in his and Nance’s cars. He is, he admits, a control freak. His wife says the best way to get him frantic is to put him in a car without a phone. “He’ll suddenly realize he needs to talk to everybody he knows.”

But the most telling aspect of Ron Chapman’s house may be his shower. Done in slick, black marble, it is an oversized rectangle, big enough for Ron “to pace in.” To pace in.

When Ron met Nance twenty years ago at a charity telethon, he was immediately struck by her good looks, he says, recalling that he trotted out a bunch of glib compliments before saying, “By the way, I’m Ron Chapman.” Her reply: “Oh. So you’re that egotistical S.O.B.”

They became fast, but platonic, friends. Many years later, both of their first marriages ended (Chapman divorced in 1982) and Ron and Nance began seeing each other, but again, just as friends. Chapman was involved at the time with a woman in New York, an aspiring actress. Nance prayed for her. “I prayed for her to have a lot of success, and I prayed that she get a wonderful starring part-and stay in New York forever.”

Nance likens her life with Ron to living with P.T. Barnum. He always has some grand scheme bubbling up to the surface, she says, and he’s always looking for some way to convince the rest of us that it’s a good idea.

Born plain old Ralph Chapman in Haverhill, Massachusetts, Ron began performing at the ripe age of three. His older sister, Florence Littauer, now a motivational speaker, used her seniority to motivate Ralph, teaching him tongue twisters and then persuading him to repeat them for amazed visitors at the store-for a small fee. of course. According to Littauer, Chapman’s massive energy manifested itself during his youth in a series of class-clown pranks.

Like the time when, in charge of locking away the band instruments in a wire cage, Ralph kept the mouthpiece of the tuba in his pocket. Passing by the cage, he would surreptitiously slip the mouthpiece through the wire into the neck of the tuba and blow. There was some serious speculation for a while in Haverhill about the Ghost Tuba Player.

In the service, Chapman was the Fifties equivalent of Robin Williams, doing a sort of “Good Morning, Korea.” On the troop ship the first night out, his sister recalls, it came time for the sergeant to hand out assignments. “Ron has never been much for physical labor,” says Littauer, “so he stood there nodding and saying, ‘Mm-hmmm’ and ‘very good, very good,’ while the sergeant gave jobs to the rest of the men.

“At the end of this, the sergeant looked at Ron and said, “What is your job. anyway?’ And Ron said, ’Why, I am in charge of the talent show,’ of which there wasn’t one at the time. For two weeks, while everyone else painted and scraped, he sat in a deck chair and interviewed people to see what their talent was.”

After Chapman had been in Korea for about a month, he got a parchment scroll commending him for lifting the morale of the troops. Says Littauer, “Only Ron could spend two weeks on a ship, do nothing, and then get a commendation for it.”

Chapman returned to the states in 1959, took a radio job in New Haven, Connecticut, and then, when a co-worker landed a job with KLIF in Dallas, Chapman went along—at $175 a week, more than double his Connecticut salary.

For a while, Chapman’s career in Dallas was on the “stairsteps to oblivion,” he recalls. “First it was six to nine. Then ten to midnight. And then they put me on from midnight to six. The next step from there would have been the street. But what me and Tom Murphy did was put together a morning show for teens, Murphy and Harrigan.” The rest, as they say, is history. Chapman was on his way to becoming, twenty years later, a small industry unto himself.

Though nobody—repeat, nobody— wants to take on Ron Chapman in public (even his roast at the Dallas Press Club last year was a three-hour valentine), friends and foes alike admit to a powerful fear of the man. To a person, everyone interviewed for this story believed that Chapman, if riled, could end his career. One former employee, who asked not to be named, speaks for many when she says, “He’s the most unfeeling, cold-hearted son of a bitch I ever met.”

And this woman counts herself among his admirers because of his “genius” at making KVIL a raging success. But her memories of her tenure at the station are not pleasant. “You’d be walking down the hall, and nothing would stop him from putting you down in a very loud voice in front of anybody. There is no excuse for making a mistake. There are no excuses in Ron Chapman’s world except ‘You screwed up.'”

Chapman isn’t surprised to hear that many former associates want deep cover before discussing his character and work style. “It’s a small industry. Everybody that works here eventually comes back around, and I’m going to be here when they come ’round again. And I do have a good memory. If someone leaves KVIL and wants, a year later, to work for Y-95, and they’ve just been in the Dallas Observer calling me a, uh, you -fill- in-the-blanks, well, they know better than to call me for references.”

Ironically, Chapman so dominates the KVIL lineup that the DJs around him seem unremittingly unmemorable. And some who have shown too much personality, critics charge, get the ax. Chapman’s cohorts speak of having to walk a very fine line; remaining clever and at least half-witty without ever being more clever than Ron.

And it’s not just the lower-downs, but the higher-ups who have their hands full of Chapman ego. Since Chapman is not only essential to ratings but is a key figure in all promotions, contests, personnel matters, etc., he is a general manager’s worst nightmare. Not only is he 110 percent fireproof and the goose that laid the golden egg, but he is shadow management, and he must be catered to and appeased. His rages and abuse must be swallowed whole. And no decision is really final until Chapman signs off on it.

Most of the radio folk we talked to have a love-hate relationship with the man. Said a Dallas radio newsman with nearly twenty years in the market, “When I left KVIL, my blood pressure dropped by forty points. My wife made me admit it publicly: yeah. I love the guy. But I got my bucketful of him a long time ago. In terms of logistics and creativity, he’s a towering genius. But he’s been trying to play ‘Creative Tension’ to the point that it became creative chaos. Imagine working in a situation for five or six years where your first question every day had to be, ‘What kind of mood’s he in today?’”

Tony Garrett got a dose of it too, though he took it philosophically. Garrett remembers Chapman’s blowing up at him for reading the same “filler” story at several news slots. “I’d just started with Chapman, and I did that two or three times before he slammed down the headphones and blew up. He said, ‘That’s the second time you’ve used that item and it’s the last! Anybody can read, goddammit! I’m paying you to write! You understand that?’ Boom! But the thing about it is, ten minutes later, it’s like it never happened.”

Michael Selden, a DJ at KVIL from 1974 to 1979, has gone full circle with Chapman emotionally, from admiration to loathing and back again. Selden went full circle in his personal life too, abusing drugs and alcohol until he wound up doing some time in what he calls the “Home for the Occasionally Coherent,” the state hospital at Rusk. Selden, now an aide at a substance abuse clinic in Tyler, believes that Chapman has accomplished what it took him much longer to do: harness a runaway ego and put it to good use.

“Chapman is an obsessive-compulsive perfectionist,” Selden says. “I have the same type of personality, just not as much discipline. He directed his in more positive directions, into the station and into work.”

Though Chapman is generally regarded, on the civic circuit, as something of a First Citizen, he has not been above exporting that inflammatory temper outside the station walls. One infamous incident occurred during last year’s gala for the National Craniofacial Foundation. Chapman had served as emcee for a couple of years in a row and had complained both times about the sound system. This time, the gala planners were prepared; the system had been checked and rechecked by technicians. But when the chairwoman greeted Chapman in the ballroom, she says, he lit into her.

“This system is awful. You people don’t listen to me, and you are going to lose $100,000 on this auction!” When she replied that the auction had never made anywhere near that much, he snapped, “That’s why!”

But stories of Chapman’s sentimentality and generosity are almost as abundant as the tales of his colossal ego. For example, co-workers wondered about his habit of dumping all his foreign currency into a drawer when he returns from trips. Turns out that a few years back, during a race around the world for a promotion, Chapman arrived late at the airport—no ticket, no cash, no passport. A man in the hotel found his passport and rushed it to the airport. Then the man loaned him enough money to buy a ticket. When the drawer becomes filled with bills and change, he bundles it up and sends it to the man.

More than one KVILite also remarked that they wouldn’t have had jobs at all if Chapman hadn’t heard that they were down on their luck and called to offer them gigs. Also, his people say that his expectations for others are not nearly as high as those he imposes on himself.

Chapman knows that he is inextricably linked to KVIL. And he admits that, in part, it is the reason his first marriage ended after nineteen years.

“The things that attracted Marilyn to me in the first place were the things that drove her crazy—the drive, the ambition, the living in the eye of the tiger eventually drove her crazy. I just never mellowed out.” Chapman admits. “I’m rough to work for. And I’ll tell you who finds it difficult to work for me. The people who don’t understand the program.”

A recent case in point, says Chapman, was the popular evening jock Lynn Haley, who was dismissed in early August. “We had several meetings in which we hoped to gain her attention about things we didn’t feel were happening correctly on the nighttime show. But she was the problem.”

Chapman, who says he agonizes over every firing and tries to help the departed financially, told Haley to find another gig by the end of the year, while challenging her to do better: “I told her. ‘In the meantime, you play every night like it was opening night, kick ass, and prove me wrong.’”

But Chapman says that the first time Haley went on the air after the deal was struck, “She was dreadful. I told her so. She said, ’How do you expect me to do a good job after all I’ve been through?’ I said, ’That’s it, we’ve been talking too long. We’re keeping you on the payroll through October.’ If she’d said, I f-ed up, I’m on the team, she’d be here still. But she never did.”

Coast to coast, when a radio station begins considering a format change, radio insiders say, the list of options goes like this: “We could go country. We could go AOR. We could go New Age. Or we could go KVIL.”

It’s a tribute to Chapman that the call letters of what is, after all, just a radio station, have entered the argot of the trade. While many have attempted to imitate his formula, nobody—at least locally—is likely to remotely approach his mastery of it.

And that’s a problem KVIL itself will have to face one of these days. Who could follow Ron Chapman? Industry critics say that while Chapman is full-tilt today, he is not really doing much to prepare his station for Life After Ron.

“He wants to control that station twenty-four hours a day, hotlining jocks in the middle of the night for mispronouncing some street name,” says Tom Tradup, now general manager of a Chicago station and, until last July, the general manager at KRLD. “I don’t believe that any one person can be in that much control and yet allow for the station to be the living, breathing organization it has to be in order to survive.

“There’s gotta be some point at which he’s willing to pass the torch. But it’s going to be hard to groom someone to replace him when he hogs the limelight and wants all the glory for himself.”

Chapman himself acknowledges his mortality, but only in the vaguest way, putting retirement plans “out there” some years down the road. “This is a first,” he admits. “I now think about retiring. It’s on the far back burner, but I think about it.

“I’ve had two scoops of everything,” Chapman likes to say. But suppose, suddenly, a rogue meteorite comes falling out of the sky and mashes him into a puddle at the corner of Mockingbird and Central? How would he like to be remembered?

“I’m absolutely realistic in believing that nobody remembers you,” Chapman says. “Maybe for forty-eight hours, max. Then by the following Tuesday, you’re just gone. Nobody’s going to build monuments or hold big memorial services.

“But if anyone were to remember me, I would hope it would be as someone who took radio disc jockeying and maybe gave it a little respect. We’ve become Kleenex. We’ve become Coke. I haven’t done it all alone, but in this company, I’ve been the thread that has taken the spirit of it through twenty years, and I think I’ve done it rather well. So if anyone were to remember me. I would hope it would be as someone who elevated the art.”

A little egotistical, perhaps. But certainly not unrealistic.