To those legions who responded to her lure, Maria Callas was opera. But had Callas been less of an illuminating musician or more commonplace as an actress, she still would have challenged the imagination with her unique, sometimes-strange, always-compelling, dark, phosphorous voice. It was one of the most expressive timbres given a singer in this century.

It was said that Bea Lillie could convulse an audience by reading the phone book. Callas could hold an audience rapt with a simple scale, each note of which contained an implied drama of its own. Next to this mesmerizing power, a sometimes rebellious top and that curious, bottled quality of her low register were minor matters.

There are those who argue that Callas demanded more from her voice than it could always deliver, and there is no denying the immense range of her repertoir, from the heroines of Beethoven and Wagner to those of Verdi and Puccini. Yet had Callas been more careful, taken less chances and remained within safe confines, she would never have been Callas.

Her greatest years were the 1950s, when she ruled as undisputed monarch of Italy’s principal opera house, La Scala. With film director Luchino Visconti, who turned to opera only because there was a Callas to direct, she collaborated on a series of productions which remain among the most fabled in lyric theater-La Vestale, La Sonnambula, La Traviata, Anna Bolena, Iphigenie en Tauride -with such conductors as Leonard Bernstein, Carlo Maria Giulini, and, in Lucia di Lammermoor, Herbert von Karajan.

She did not come, however, to the stage of Scala quickly or easily. Her career was an extraordinary exercise in will-power and hard work. After her debut in Italy in 1947, the real beginning of her professional career, there were few engagements at first, She was something new to listen to. Her voice disturbed as many as it excited, and her interpretations made audiences work harder than with other singers.

Born in Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue Hospital to Greek parents who had only months before immigrated to the United States, she was christened in full Hellenic splendor as Sophia Anna Maria Cecilia Kalogeropoulos. By eight she was studying piano, and at ten singing arias from Carmen. Three years later, her mother returned to Greece, taking with her Callas and her older sister. She soon came to the attention of Elvira de Hidalgo, a soprano who sang at the Metropolitan Opera during the time of Caruso, and who had been stranded in Athens with the outbreak of war in Europe.

“The very idea of that girl wanting to be a singer was laughable,” de Hidalgo later recalled.” She was tall, very fat. and wore heavy glasses. When she removed them, she would look at you with huge, but vague, unseeing eyes.” But when Callas sang, “I heard violent cascades of sound, not yet fully controlled but full of drama and emotion. I listened with my eyes closed and imagined what a pleasure it would be to work with such material, to mold it to perfection.”

When the war ended, Callas returned briefly to New York where she was offered a contract with the Metropolitan Opera, one she did not feel she was ready for. Instead, she accepted an engagement as Gioconda at the Verona Arena. The year was 1947, and she made her Italian debut with another young American, Richard Tucker. These performances proved as important to her as her meeting with de Hidalgo, for the conductor of those “Giocondas” was Tullio Serafin. He was to be as influential in Callas’ career as he had been twenty years earlier in the career of Rosa Ponselle.

Though Callas began her career as a dramatic soprano -Gioconda was followed by Isolde, Turandot, the Forza del destino Leonora, and Aida -it was Serafin who understood his protegee’s true nature, that she had the resources to bring back to opera a vocal type which had virtually been extinct in this century -a dramatic soprano with the ease and high notes of a lyric, the wedding of agility to power.

Callas’ final operatic appearances were given in 1965. She was only forty-one, She had reached a crisis in her singing which had come about through a wrench in her private life. Nicola Rescigno, who conducted Callas’ American debut in Chicago as Norma in 1934, and who later collaborated with her in concerts and on records, has explained the impasse Callas faced with these words: “When Maria was living the life of a vestal virgin, so to speak, it was home-theater-home. A dinner out was a big treat and an exception. When she broke that discipline, it was not the voice, I think, which suffered. It was the whole mechanism, for her voice had become a highly oiled machine which produced inhuman effects. . .I don’t think Maria herself realized exactly what went into her singing; it had been so ingrained for so long by her way of living, of thinking. It had become a completely natural thing. When this naturalness was no longer there, it shocked her, and she couldn’t fully understand it or cope with it.”

The legend of Callas, however, was already set by this lime. Even an attempt to return to the stage in a concert tour in 1973, with a voice largely unresponsive to the needs of music, could not diminish all Callas had achieved and all she stood for. During her long career, she had lent new lustre and meaning to the words “prima donna.” But to think of her only as the first lady of opera is to miss her ultimate importance. She was a revolutionary who turned the operatic world upside down and reset its course. She made her audiences revalue opera as a forum of expression through carefully built and integrated portrayals which were as moving musically as they were dramatically.

It is on this the legend rests, not on the controversial, highly publicized personality, and the printed maze of truths, half-truths, and fiction which frequently obscured the real artist and musician. Distortion is usually the residue of enormous fame. It is a price Callas paid, either willingly or unwillingly, for her uniqueness, What mattered more in an age of pre-packaged art and faceless music-making is that she stood apart from the crowd with a resolute sense of her worth and of her responsibilities to art. She followed her star doggedly, and it burned brighter than any other in the post-war operatic heaven.

Her career was bought at great price, but who would have had it otherwise, and who is not proud to say they were a pan of the age of Callas?

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

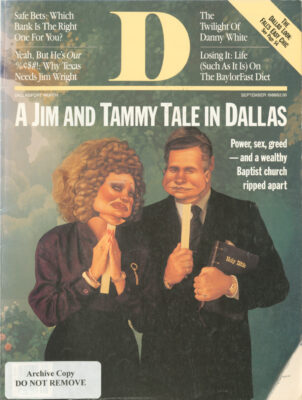

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte