Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

The corner of Bryan and Fitzhugh is a quiet place near midnight. A 24-hour 7-Eleven draws occasional clusters of people making last-minute beer runs. An Oriental seafood market used to occupy one corner, but it burned down a couple of years ago. Hall’s Hobby House, bristling with burglar bars, and Jimmy’s Food Store occupy the other two points of the intersection. Both stores close in the early evening.

The night is warm, unlike the night of February 27, 1987, when it rained hard and a cold wind blew. I gather my courage and ask a lone man if he knows anything about the events of that night. He does not. Another does not speak English. So I stand and watch. I’m waiting, I suppose, for the man who killed my brother.

In my imagination I have seen him a dozen times, appearing out of the shadows. He slowly walks into the center of my vision, not knowing I am there, and surveys the scene, looking satisfied. I picture him through a secondhand description of a man seen by a 7-Eleven customer that night. He is Hispanic, dressed in a blue T-shirt and red headband.

How convenient, and how much like a cheap crime novel. The return to the scene. I would silently walk up to him, taking him by surprise. Before fleeing or coming at me with a knife, his eyes would meet mine, and in that instant I would know that he was the one.

Of course, nothing happens. The night brings no neat resolution to this baffling crime and no answers to the questions that have haunted my family for 18 months and may haunt us forever. I am in bed by 1 a.m., thinking as I do every night of my brother’s death and the life that preceded it.

•••

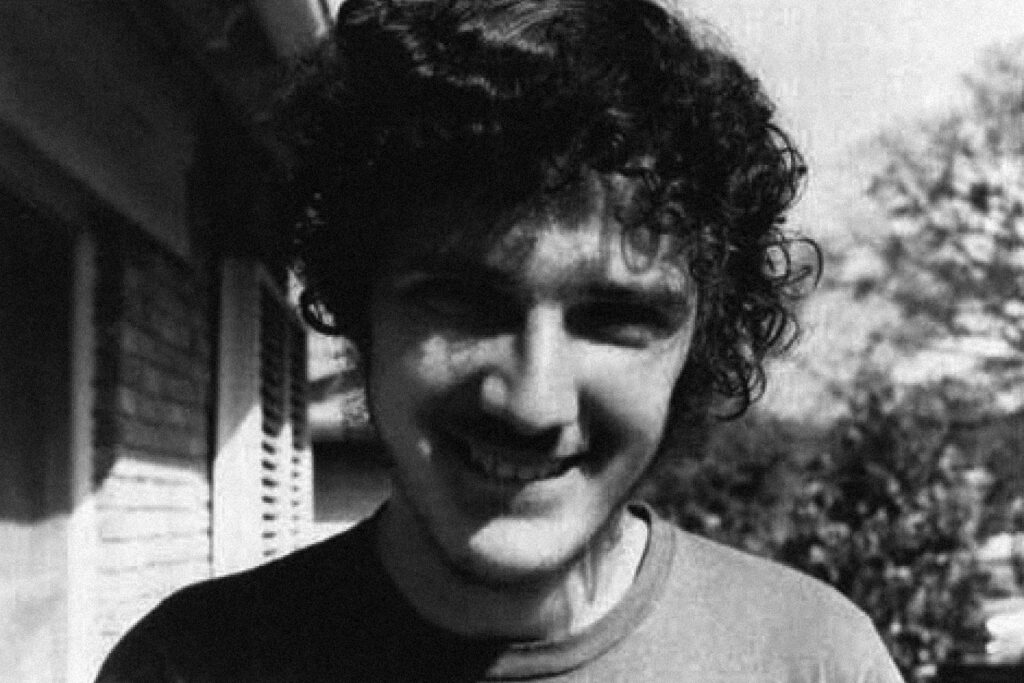

“Dan, this is Dad,” I vividly remember the voice inside the telephone saying early one Saturday morning. “I’m afraid I have some very bad news. Paul has been mugged.”

After a long pause, he answered my unasked question: Paul had suffered “massive brain damage.” We were on the phone for about 20 minutes, much of it silence broken by sputtered phrases of disbelief. Somehow arrangements were made for me to take the next available flight out of New York to Dallas.

In the middle of the conversation, my dad started talking about Paul in the past tense. My brother was not expected to be alive when I got home; he was lying in a coma in a Baylor hospital intensive care unit, being fed intravenously. He was attached to a respirator and a host of other machines. Paul had sustained numerous stab wounds in the face and head, probably from an ice pick. Two of the wounds had gone all the way through his cerebral cortex into his brain stem.

It was a nightmare, the days I spent with my family, seeing him breathe through a tube, strapped down on his bed. I watched his eyelashes flicker, wondering if he was going to die, live to be a vegetable, or live to be my brother again. We all hoped and those who could prayed. A series of doctors explained things to us. We were ready to commit everything we had to whatever recovery he could sustain. We talked about what meaningful life was, about whether what the doctors did was merely protracting, or potentially enhancing, his life. Then, after 13 days, he died.

We pieced together a few details about the attack. Paul had gotten off his bus at Live Oak Street late that night and walked through a neighborhood east of downtown where slums meet urban gentrification projects, where PTA meetings are often held in four languages: English, Spanish, Khmer, and Vietnamese. He was on his way to work the graveyard shift at the Seidler Community House, a halfway house for first offenders located on Fitzhugh. It’s an area dotted with apartment buildings—low rents and high crime rates. He was attacked at the corner of Bryan and Fitzhugh.

The police have no suspects and no motive. The man with the red headband may be real and he may not be. About all that is reasonably certain is that the killer was not a Seidler House resident; they were all accounted for that night. I am therefore left with neighborhood drug dealers, former Seidler residents, random killers, and just about the rest of the city of Dallas to consider as my brother’s murderer.

I wish someone could tell me what Paul’s death was about, that Paul’s killer was psychotic, that he came from a broken family, that he had to prove something to someone, that he was conditioned by too much violence on television, that he wasn’t breast-fed as an infant—something. But there is only an investigating officer who says the case is still open and that he can’t eliminate “just pure meanness.”

Who would want to kill someone who never raised his voice, rarely imposed his will or even his opinion on anyone else?

Suffice it to say no one remotely understands this crime. Behind the statistics about random urban violence, the questions lurk. Who would want to kill someone who never raised his voice, rarely imposed his will or even his opinion on anyone else? Who would want to kill someone who spent much of his free time in church and Sunday school classes or reading the Bible to himself? Who would want to kill someone born with what is alternately called severe dyslexia and minor brain damage? Who would want to kill someone who, after struggling with his handicap through high school and most of college, decided that his calling was in helping those less fortunate than himself? Who, and why?

Most people who grew up in Highland Park, as Paul did, have rarely set foot near anything like Seidler House. It is the type of facility they have rarely seen and would fight with all they have to keep out of their neighborhood. Though Seidler houses only those who were convicted of nonviolent crimes, the residents are hardly pillars of the community. Many of them did something to violate the terms of their probation. A high percentage of them come from difficult home situations or no home at all. After spending their allotted time at the house, they often stay in the neighborhood and come back to the house for counseling, to chat, or just to watch television.

Seidler House and its parent Homeward Bound, both nonprofit, nonaffiliated organizations, see their function as providing a drug-free, violence-free environment and people to talk to during a critical time in a convicted criminal’s life, a time when a little home life and a little support could be enough to keep him from committing another crime. Residents must either have a job or be looking for one, with Seidler’s help. Everyone is expected to participate in the upkeep and governance of the house.

Paul’s normal duties included making sure residents came in when they were supposed to, fixing sandwiches for their lunches, waking people up in the morning, taking care of a little paperwork, and just being available if anyone wanted to talk. Occasionally there would be a fight or argument among the residents, and Paul would unemotionally walk up, cross his arms, and ask what was going on. “He had a way of making a person calm,” says former resident Alonzo Williams. “Maybe it was his voice. I don’t know.’”

If asked, Paul would say he did his job to give those down on their luck another chance. A few days before Paul was attacked, my dad asked if he should keep his eye out for any jobs. Paul said that if he could find a similar job that paid more, that would be fine; otherwise, no thanks. Paul was making about $6,000 a year.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author