Neither a borrower nor a lender be; For loan oft loses both itself and friend, And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry. This above all-to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man. Polonius to his son, Laertes, Hamlet

HAVING SURVIVED 1986, THIRTY-SEV-en-year-old Craig Hall takes to heart at least half of this fictitious father’s parting advice. And you might be surprised to find out which half. During the past year, Hall has dealt with debt restructuring of tragic proportions, he has seen loans test friendships, and he has been under tremendous stress. But Craig Hall continues to be both a borrower and a lender.

No, it’s the second part of Polonius’s advice that Hall holds closely-the part about being true to himself. It may be that he follows it too closely for his own good.

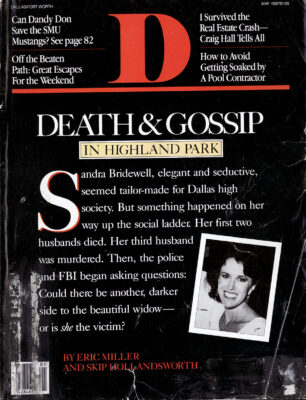

When Craig Hall was flying high, building an investor base of 10,000 individuals, amassing 60,000 apartment units and several million square feet of office space, the press was the first to know. When that empire began to crumble with the Texas economy, again, the press was the first to know. During the past year anyone who has picked up a newspaper is familiar with the Craig Hall mug, first with mustache, then without. The press latched on to Hall’s precarious relationship with his tenders- not terribly different from that of most other syn-dicators or developers in the Southwest-because Hall was talking, Hall was accessible. Shoot, Hall was issuing press releases about his loan problems-problems that others were only whispering about in private offices, with the doors closed. He was an easy example. He was the biggest example. He was the quintessence of the tumbling Dallas real estate market. Craig Hall came to represent the plight itself.

Yet listening to Hall’s friends, critics, peers, investors, business partners, and advisers describe Craig Hall is like watching reruns of “The Andy Griffith Show.” You can always count on Andy to do the right thing. The pool of adjectives used to describe Hall remains consistent, with only the order changing from speaker to speaker: straightforward, honorable, candid, ethical, trustworthy, forthright. There’s more to the Craig Hall you’ve read about, the fellow whose name has appeared in the paper either before or after the word “bankruptcy” for the past year. A little surprising? Read on.

CRAIG HALL NEVER REALLY WANTED to be a businessman. He wanted to be a poet. No kidding. Sit under a tree, grow a long beard, the whole bit. He also says that he wanted to be a social worker. Honest. He says he spent time working with kids in the slums of Chicago. But business was something that came naturally to Craig Hall. When he was twelve years old, a drugstore in his neighborhood in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was going out of business. In that failure, Hall saw a business opportunity. For fifty cents (“a quarter down and a quarter on deferral”), Hall bought the drugstore’s entire inventory of Green Rivers, a soft drink syrup. Hall can’t remember just what a Green Rivers tasted like. (’”I didn’t drink the stuff. I sold it. That would have cut into profits.”) But he can remember a very important lesson he learned at this proverbial lemonade stand.

“The biggest problem with the business was when I ran out of syrup, there wasn’t any more. That’s how I learned about the oil and gas business. It works the same way. When you sell it, it’s gone,” Hall says, only half joking.

And so began the business career of real estate syndicator, racquetball club developer, venture capitalist, stock market investor, former Dallas Cowboys owner Craig Hall- a career marked time and again by both winged rise to success and rapid fall toward failure. And Hall, always consistent, ever resilient after being stretched, bent, and hammered upon, recovers his strength and good humor, arms himself with intellect and one-liners, and starts again.

Hall’s first venture into the real estate business began while he was enrolled at Eastern Michigan University. It wouldn’t be entirely accurate to say that Hall was a student there. He says that he never took school very seriously; it was secondary at best, but he was enrolled for a full load of classes. He also worked forty hours a week for a while at the University of Michigan hospital moving equipment, then as a projectionist (“showing movies, now that was one of the better jobs I had in my life”), shoveling gravel off a truck, and as a night watchman. Somewhere in there he found time to buy and manage a portfolio of real estate. In 1968, at age eighteen, Hall spent his $4,000 savings on a rooming house for students. In a fairly short period of time, Hall had acquired twenty rooming houses (“they were kind of like rabbits”) and secured management contracts for other properties. Beginning with his second building, Hall became a syndicator (“because 1 didn’t have any more money”) and sold limited partnerships to other students in $250 units.

“But if they wanted to invest less, or give me a note, stretch it out, give me a Mickey Mantle card, whatever. 1 took anything,” Hall says.

Hall jokes about it now, makes it sound easy and fun. In those days he drove a flashy Corvette. (“Blue to match my eyes. But I had to sell it to support the buildings-negative cash flow.’”) He describes owning and managing student housing as “interesting.”

“When marijuana became very popular back in ’68 and ’69. that was good. It made people mellow and they didn’t do a lot of damage. But when beer came back in ’71, you could judge how good the parties were from the hallway. If there were less than fifty or sixty kicks through the dry wall, it was a slow weekend.” Hall recalls.

Those were tumultuous times to be in the apartment business, the days of rent strikes, landlord-tenant consumerism, Nixon’s rent freeze. At one point in the early Seventies- about the time Hall dropped out of college, permanently-he changed the name of the company from Hall Real Estate to Standard Realty Corporation. “Everybody used to call up and ask for Mr. Hall and it seemed like it would be better to be more innocuous,” Hall says. Standard Realty it was.

Tired of picking up beer cans at his properties on Monday mornings, in 1971 Hall got out of the student housing business. He began syndicating “real people” real estate and managing what he calls “the worst properties that no one else would take.”

Each year, Hall syndicated bigger and bigger deals. At age twenty-three his company | bought a S10 million property. At twenty- ! four, Hall syndicated a $25 million property. | During those years, Hall became an expert at taking poorly performing apartment prop-erties and making them profitable. But that hard-won expertise took its toll. By 1975, Hall had had enough of the real people real estate business, too. He retired from his company (retaining ownership), got a divorce from his first wife, and went to Europe. There he began the first of two books. The Real Estate Turnaround: Craig Hall’s Investment Formula That Makes Millions, about his company’s methods to revive financially stressed real estate. {The book was published in 1978.) Thus, Hall closed a chapter in his life-only to begin another.

HALL’S NEXT VENTURE BEGAN WITH AN act of chutzpah. After his return from Europe, Hall and friend Marty Rom were sitting around talking about what Hall was going to do with the rest of his life. The now-forgotten racquetball craze was just gathering momentum and Hall decided to go into the racquetball business. What he needed was cash. He and Rom made a list of seventy-five corporations to approach with partnership propositions. The first one on the list was Time Inc. Hall thought Time would be great, especially if it would license the use of Sports Illustrated to name the clubs.

“Because I was a little shy and withdrawn [right, Craig], Marty, who is much more outgoing, was going to see if he could get anyone to put money in. If he did, he would get 10 percent of the company. I would do all of the work, put some money in, and get the rest, minus what went to partners. So, Marty picked up the phone and called the son of the founder, Henry Luce. He got through right away, and he said, ’Hank, Craig and I are going to be in town next week. Let’s go to lunch.’” Hall swears that’s just how it happened.

Within ninety days, Time Inc. had given Hall a million dollars and a name-Sports Illustrated Court Clubs. A year and a half later, in 1977, Hall realized that the business wasn’t working, That’s really an understatement. It was a dismal failure. They started liquidating. They are still liquidating.

“We go to closings when we sell them and we write checks. We are happy to write checks,” Hall says.

What’s really amazing about the racquet-ball clubs isn’t the Time Inc. connection, or the fact that individual limited partners poured $14 million into these less-than-fruitful deals, but that the investors didn’t lose money. In 1978 and 1979, Hall’s advisers were telling him to file for bankruptcy on the racquetbalt business. But Hall didn’t. His real estate business was making enough money to support the failing clubs. Why did he throw good money after bad?

“I felt a certain sense of commitment to those individuals. It’s a hard thing to explain, but I think they invested in it relying heavily on me. I just felt it was the right thing to do,” Hall says.

He’s right. Alan and Mari Loofbourrow invested in the racquetball venture because they were impressed with Craig Hall-not because they had analyzed it and found it a potentially profitable deal. The Loofbour-rows met Hail in Detroit while he was selling the Sports Illustrated Court Club deals. One of Hall’s friends introduced them to Hall over lunch.

Says Alan Loofbourrow about the racquet-ball deal: “You can’t win them all. Craig stuck by us. We didn’t make money, but we didn’t lose any either.” And here come The Adjectives: “I worked for Chrysler for forty-two years and retired ten years ago. I have never met a more frank, honest, straightforward, forthright man. I don’t know anyone who has lost any money with him.”

Now does that sound like the dastardly fellow we’ve been reading about lo these many months? What gives, Craig?

It seems that Craig gives. Last year, when the real estate market turned increasingly sour, Hall could have walked away with millions. Instead he took $85 million of his own money, raised from the liquidation of assets, including the sale of his interest in the Cowboys, and put it into the floundering apartment properties to protect his limited partners and their investments. Hall has not had one lawsuit from an investor. Instead, he has received more than 500 letters of support from investors, many of them praising Hall’s frank partnership communique’s. Out of 243 Hall properties, six have been surrendered to lenders. In each of those cases, Hall says he has accommodated the investors so that they would not suffer an immediate loss. Hall ended last year with a 1.4 percent delinquency in partnership payments-a good record in even a good year. Why? Because Hall’s investors trust him. By now you are probably thinking this is all too good to be true. But wait, and a few human characteristics do appear. Craig Hall doesn’t walk on water-although some people say he has walked on thin ice.

“You can’t carry the weight of the world on your shoulders. People make an investment and they certainly realize there’s some risk. When things go better than was expected, I’ve yet to find anyone come back and say, ’Gee, it went a lot better than you told us. Here’s a hundred thousand, fella,’” Hall says.

BY 1979, HALL HAD MOVED BACK INTO THE real estate business full time. His company had an eye on Houston and began to buy apartment properties there. In 1981, Hall opened a branch office in Dallas. His attraction to Dallas was a natural one. In many ways, high-flying Dallas was much more suited to Craig Hall than conservative, midwestern Michigan.

“I think Dallas has a lot of appeal for someone with my personality-the entrepreneurial, positive, can-do attitude, the growth. There are a lot more real estate activities here than in the Midwest and I just thought it was a good way to expand horizons, personally and professionally. It felt good in that sense,” Hall says.

By 1983, Hall was spending more and more of his time in Dallas, and he began to think about moving his headquarters here. He had remarried by this time, though he jokes that he can’t quite remember when. “I think it was after the first book and the trip to Europe. It fit in somewhere. MaryAnna and I got married in a lunch hour, I remember that.”

Many people say MaryAnna Hall is one of Craig’s prime sources of strength. It is easy to conclude that her support through the past year’s events has much to do with Craig’s resiliency. This beautiful woman, six years his senior and also married for a second time, is typecast by many as the “strong woman behind the successful man.” Of MaryAnna Craig says: “I am very fortunate to have such an understanding wife. Anyone who knows both of us likes her better. I really think I’m just the pretty face. She’s the intelligent one.”

Surprisingly, it wasn’t a lagging Michigan economy that turned Hall’s head to Texas.

“I actually like bad economies,” Hall says. “In my view, as a company, we have always done better in a bad economy. When we moved into Texas, the problem we had was that we couldn’t afford to compete with all of the big guys. We didn’t do much business until things really started to turn bad here and then it kept getting worse and worse and worse. We did a lot of business that we really could have waited on a while. But the fact is, I would rather move into a bad market than a good market.”

So as the Texas economy turned downward, Hall Real Estate grew fast, becoming the largest owner of apartments in the state. And Dallas began to embrace Craig and MaryAnna Hall. Hall found himself welcorned into the fold of one of this city’s most prestigious, old-line society circles-the Dallas Symphony board. And the various boards that Hall served on found something rare in Craig Hall-a working board member.

“I don’t like my name on something that I’m not active on,” Hall says. “A lot of people join boards who aren’t real active and I don’t think that’s the right thing to do. But in 1986, I kind of dropped off the face of the earth. I either have or am resigning from a lot of things. My first duty is to my investors and I need to take care of priorities.”

So what was going on when Hall dropped off the face of the earth in 1986? Hall says he has always worked between eighty and ninety hours a week, which explains another one of The Adjectives used to describe him- workaholic. But those hours were split, he says, with about 50 percent spent on the real estate business and the rest divided between his other business ventures and civic activities, admittedly leaving little time for his wife and their daughters. Last year, though, Hall says he worked between ninety and a hundred hours a week-all devoted to the real estate business.

Hey, everybody who was in the real estate business a few years ago is in the workout business now, right? (A “workout,” for non-members of the Sleepless Nights Club, means the restructuring of debt that cannot be paid as originally scheduled. Chrysler is a well-known company workout. Mexico is a well-known country workout.) Hall’s case was particularly newsworthy because his problems last year were of a magnitude that made people shudder. Before year’s end, he had completed 86 percent of the company’s financial restructuring-$930.3 million of the total of $1,088 billion in partnership and corporate debt.

Even before any of his properties were in default to lenders, Hall was talking about the problems to come. In December of 1985, he saw that the economic situation in Texas- which had been getting worse for some time-was not going to improve to the extent that would help his properties maintain their debt. So, he went to some of his biggest lenders to lay it all out on the table.

“I then realized that most of our biggest lenders were in financial default and were controlled by the government,” Hall says.

So on December 20, 1985, Craig Hall went to Washington for his first meeting with The United States of America. “When I first saw the degree of problem we had, my con- , cern was, selfishly, for the investors. But it was also for the system,” Hall says.

His concerns were and are valid. For Hall’s is not an isolated problem that can be explained away with phrases like “bad management.” Where did he, and many, many others, go wrong?

Hall’s theory is that his syndication deals were structured to make money in an inflationary environment, while Texas has gone rapidly from a period of inflation to a period of deflation. That means apartments that were built in the late Seventies and early Eighties would remain profitable as long as values and rents continued to go up. But rents and values went down, and in that same period, interest rates fell drastically. New apartment complexes built with low-interest loans went up next to old apartment complexes built with higher-interest loans. Those new properties could charge lower rents and still make money, which forced rents even lower and made it difficult for the older properties to keep up with loan payments. And vacancies were climbing. Normally, when values are declining, construction slows. But not in Texas in the early Eighties.

“New construction continued because there was a lot of land that was available and there was a lot of momentum,” Hall says. “As long as there is lending money, builders will build and developers will develop. It’s not market demand that controls the process, it’s money. It took me years of being in business to realize that simple fact.

“My view of the market in 1984 and 1985 was that it was overbuilt, headed for problems; it would dip down a little ways and then start to come back up. We would just buy right through that period and be fine. Well, everything went to a much greater extreme than I think most anyone could foresee,” Hall says.

So, restructuring was upon him. Unfortunately, there is no course on loan restructuring at banking school. This is not something people plan for-there is no given protocol, no typed agenda, no handbook. Hall’s plan, and a successful plan it was. is another example of his being true to him-self-yes. The Adjectives again.

Soon after his meeting with Uncle Sam, Craig Hall had a meeting with Kenneth Leventhal & Company, an accounting firm that specializes in real estate work. A million dollars later. Leventhal delivered to Hall what he calls “the facts of the situation.” Hall lugged fat volumes of these facts on each and every Hall property, each and every Hall asset, to each and every lender. (For details, see Hall’s How-to Tips For a Successful Workout, this page.) Craig Hall, very typically, bared it all. With more than one hundred lenders, honesty was definitely the best policy.

Ken Leventhal first met Craig Hall in December 1985. In many ways, Hall is just another client to Leventhal. His firm specializes in real estate problems. When the Tram-mell Crow Company was having problems in the Seventies. Leventhal & Company was here picking up the pieces for Crow. And Craig Hall isn’t the firm’s only client in Dallas right now. Leventhal says that Hall misjudged the situation “because the three things he was banking on went to hell” (an expanding economy, inflation, and tax break incentives for real estate limited partnerships). But he too speaks of Hall in The Adjectives: “He’s the most resilient guy I’ve ever met.”

Bill Criswell, a real estate developer with his own set of problems, says he is just one of many people who have felt a kinship with Hall and have been inspired by his actions. “The world is so full of guys who would cut and run.” Criswell says, “but he used personal funds to shore up the properties.”

Jim McCormick, retired vice chairman of Eppler, Guerin & Turner Inc., has known Hall for seven or eight years, ever since he served on the board of a company in Detroit in which Hall was a major stockholder. He’s watched Hall live out the worst year of his life. “He has gone through more stress than the average human could cope with, and one of the reasons the stress has been so great is because he is so honorable and ethical.”

Wayne D. Benson is a dentist in Auburn, California, and an investor in one of Hall’s limited partnerships. In a letter to Hall, Benson wrote: “I would like to express my appreciation for the professionalism that you have demonstrated during this ’counter cyclical’ and trying lime.. Thank you for standing behind your word! My contribution to the limited partnership will be on time.”’

Ahh, those are sweet words to the ears of a syndicator.

SO. IS THE RESILIENT CRAIG HALL READY to sell the blue Corvette-actually, it’s now a blue Cadillac-and take another trip to Europe? No. Believe it or not. he’s actually asking for more of what he got last year. Even though Hall says restructuring debt is “one of the most humiliating, personally trying, absolutely agonizing experiences,” even though he says the last year was like “rebuy-ing l.l billion dollars worth of property in a short time with somebody having a gun at your head,” he’s going to do it some more.

Why? No, not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because he is being true to himself, to the Craig Hall way. There is a business opportunity in workouts just as there was a business opportunity in Green Rivers, and he sees it.

“We are negotiating right now and are getting more and more active in taking over smaller syndicators who aren’t going to make it,” Hall says. “We have a good relationship with a lot of lenders. We’ve (level-oped good credibility. A lot of people felt during the worst times in 1986 that there would be a breakíng poínt, that we would get up and run away, which I don’t think would have been too advantageous. So with the apparatus we’ve built up to keep ourselves going, we are going to see if we can help others and make money at the same time.

“I have always thought that was the essence of free enterprise. You find a need and you fill it and you make money,” Hall says. “We have a temporary need here, At least I hope it’s temporary.”

Pat yourself on the back, Craig. Polonius would have been proud.

Craig Hall’s How-to Tips For a Successful Workout

1. “The first thing is to get your arms around the facts of your situation.”

In Hall’s case, that meant hiring an outside service, Kenneth Leventhal & Company Certified Public Accountants. For the roundabout price of a million dollars, Leventhal & Company inventoried every Hall property, every Hall corporation, and compiled a realistic financial cash flow for the whole shebang.

2. “Next, stand back from the situation and put together a realistic game plan. . .whether it is an exit strategy or a continuation strategy.”

After having gone through the most intense year of his life, Hall concedes that some people may not have the stamina to succeed in the workout arena. “If you don’t have enough pieces left in the right places to make it work, if you don’t have the stamina, then figure out the best way to exit that is fair to everybody and that will give you a chance to come back and fight another day,” Hall says, “If it’s an exit strategy. I would recommend it be done with honor and class and in a clean manner.”

Hall recommends getting ideas from many sources and stresses that the workout game plan should make sense for the creditors: “They need us and we need them, but the truth is we are the ones in default, and when push comes to shove, we need them a lot more than they need us.”

3. “Take your comprehensive game plan and deal openly with each of the cred itors so that each knows what you are giving the other.”

Lenders get frustrated, Hall says, if they don’t think they have all of the facts. Each lender tends to think other lenders are getting their money. In Hall’s case, each lender got volumes of information; every property, every corporation, every dollar laid naked before them. “Do you know how it got in the papers that I paid my house off in January last year? Because it’s in these books,” Hall says, pointing to the documents given to the lenders. “We didn’t try to hide it. We put it in as a separate line item. Because if anyone has any questions, I believe they shouldn’t have to wonder.”

4. “Stick to your plan. Don’t negotiate lots of side deals with different people because it will destroy the integrity of the plan.”

Hall says this was the most difficult part of his workouts. Although the lenders were included in the planning process, when it came down to the wire, “we presented it and stuck to it.”

5. “The last bit of advice is, if you are do ing the right thing and you know that you are, have confidence in yourself, be as positive as you possibly can, and work your tail off to get it done.” -S.G.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain

Things to Do in Dallas

Things To Do in Dallas This Weekend

How to enjoy local arts, music, culture, food, fitness, and more all week long in Dallas.

By Bethany Erickson and Zoe Roberts

Local News

Mayor Eric Johnson’s Revisionist History

In February, several of the mayor's colleagues cited the fractured relationship between City Manager T.C. Broadnax and Johnson as a reason for the city's chief executive to resign. The mayor is now peddling a different narrative.