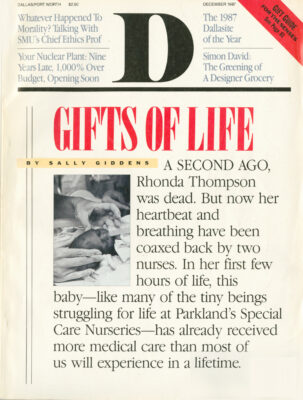

A SECOND AGO, RHONDA THOMPSON WAS dead. An alarm sounded, signaling that her breathing had stopped. Now. her heartbeat and breathing have been coaxed back by two nurses. An attending physician, a resident, and two interns hover around her. The doctors have just inserted a chest tube along the outer walls of her lungs, which are not yet developed enough to expand and contract normally. Air is leaking through too-thin membranes. She’s having trouble breathing, so the nurses insert a ventilator tube through her mouth and into her windpipe. An IV in her foot is used to administer various drugs; another, inserted into a vein in her head, feeds her. When Rhonda (not her real name) is stronger, a feeding tube will be inserted through her mouth and esophagus into her stomach to give her formula. She can’t take a bottle; she’s too young to know how to suckle.

In her first few hours of life, this baby-like many of the tiny beings struggling for life at Parkland Memorial Hospital’s Special Care Nurseries-has already received more medical care than most of us get in a lifetime. The term “intensive care” is really an understatement, because the attention these nurses and physicians give her is constant; they don’t leave her bedside. They all gather around her miniature body-no longer than the nurse’s hand-to keep her alive, Ten adult: hands all work at once on this tiny infant, who weighs a mere eighteen ounces-just a little more than the magazine you’re holding. Nothing is wrong with Rhonda, except she was born twenty-four weeks into gestation-four months too soon. Her skin is nearly transparent; the piece of tape that holds her ventilator tube in place could tear her skin if not pulled gently from its place. Just a touch can bruise her. Rhonda has come from a quiet, undisturbed atmosphere in her mother’s womb, But she’s been thrust into a foreign, life-threatening place filled with the cacophony of these beeping and buzzing machines and these adults who further her life. She is so unready for the world that the shock of loo much noise can stop her breathing, But something happened to trigger her birth, and she’s one of more than a quarter of a million premature babies born in this country each year. So new in life, yet so close to death, Rhonda looks strangely adult, somehow wiser than the full-term infant we picture as plump and cooing. This baby seems to be all arms and legs, long and spindly, spiderlike. Her tiny hands have straight, adult Fingers uncurled for lack of baby fat. Her large, shining eyes stare right through you while the nurses and doctors keep working. She looks so pitiful, so hopeless with these tubes and wires and needles protruding from practically every inch of her body. But the doctors and nurses keep trying. They know there is hope for this baby. They’ve seen the successes-the ones who wouldn’t have had a chance of living if they’d been born even five years ago-leave the Parkland Special Care Nurseries and go home. And they’ve seen the successes come back as rambunctious toddlers and healthy, growing children to celebrate at Parkland’s annual preemie Christmas party. This holiday celebration renews these nurses’ strength and helps them feel a satisfaction with a grueling, emotionally demanding profession that most of us can only imagine.

THE NUMBER OF BABIES PARKLAND DELIVERS EACH YEAR is staggering-in 1987 alone, more than 15,000 babies will be born there, roughly the number of people living in Waxa-hachie. Births at Parkland have climbed steadily since 1974 when approximately 6,500 babies were delivered. But the upward trend has been markedly more steep in the last several years, compounded as Parkland’s share of the county health care burden grows larger. In 1984, Parkland handled 32 percent of the total number of births in Dallas County. Parkland’s share of the county’s deliveries increased to 36 percent in 1985, to 38.4 percent in 1986, and is expected to hit 39 percent for 1987. For many reasons, Parkland’s responsibility has grown while private hospitals compete to fill empty hospital beds. The most obvious cause of the increase is the economic state of Dallas County. With more people felling under the label of “indigent,” more unemployed workers without insurance, more companies reducing or eliminating their health care benefits, the buck finally stops at Parkland, the public’s hospital.

And in Parkland’s Special Care Nurseries the indigent health care problem is magnified. Babies are in the unit for three reasons: they were born at thirty-seven weeks gestation or less (forty to forty-two weeks is considered full term); they were bom weighing less than five pounds; or they were born with physical problems. Though researchers don’t yet know exactly what triggers premature birth, health care workers do know that poverty is an important determining factor: there is a direct association between badly nourished mothers and early delivery. Poor women have more low-birthweight and premature babies than do women in any other socioeconomic group. Black mothers, more susceptible to high blood pressure, are also in a higher risk group. And the population that Parkland serves is largely black and mostly poor. Teenagers are also prone to deliver prematurely, and in 1985, almost a third of the women who had their babies at Parkland were between the ages of thirteen and nineteen. Twelve-year-old mothers are becoming more common. Lack of prenatal care is also an important factor in premature birth. While the average pregnant woman under an obstetrician’s regular care will make at least twenty-five trips to the doctor’s office before she delivers, nearly 20 percent of the women who delivered at Parkland in 1985 had no prenatal care whatsoever. These are the mothers whose babies end up in the Special Care Nurseries. And these problems, all getting worse, contribute to the increased demand on those special nurseries at Parkland.

The intensive care area of the Special Care Nurseries has fifteen beds. They stay full, and they cost between $1,500 and $2,000 a day-not including any surgery or special procedures. The thirty-five beds in the acute care area of the nurseries are at least that expensive, and the remaining thirty-five beds- the ones for the “growers” just waiting until they weigh enough to go home-cost a minimum of $550 a day. These nurseries are one of the more expensive areas of the hospital. At 100 percent occupancy the bills are more than $30 million a year. And only a small percentage of those hospital bills are ever recovered by the county. Approximately 8 percent of Park-land’s Maternal/Child Health patients are on Medicaid; for the obstetrics area as a whole, about 12 percent of the hospital’s costs are recovered, according to an analysis made two years ago. And the demand for care keeps on growing. In Parkland’s 1987 fiscal year, which ended September 30, more babies needed help from the Special Care Nurseries than ever before-1,771 infants were admitted into the unit, making it the busiest neonatal special care unit in the region. About 12 percent of total births at Parkland last year were sent to the Special Care Nurseries, a higher percentage than in years past. Nurses in the unit say they feel like they are seeing more and sicker babies each year. The numbers bear them out.

Parkland has been a pioneer in the field of neonatology, and the unit’s success can be measured in the improving survival rates for smaller and smaller infants. Dr. Charles Rosenfeld, medical director of the nurseries and professor of pediatrics, obstetrics, and gynecology for Southwestern Medical School, says that in 1973, babies weighing less than 2.2 pounds just did not survive. Now, babies of that size born at Parkland have a 45 to 50 percent chance of living, and Rosenfeld says the good news is directly attributable to better nursing care. In 1981, twelve babies per thousand died at Parkland. The next year, thirty new nursing positions were added, significantly lowering the nurse-to-baby ratio. Since that time, the hospital has lost just seven babies per thousand-a radical improvement.

The Special Care Nurseries at Parkland have been Rosenfeld’s baby since 1973 when he began planning a small neonatal intensive care unit. That unit, the precursor of the Special Care Nurseries, opened in what once served as a formula preparation room. Parkland’s commitment to the Special Care Nurseries has grown over the years, Rosenfeld says, and though it is an expensive area, he adds that the cost effectiveness of a neonatal intensive care unit can be much greater than many forms of intensive care for adults, given the payoffs for success. “You’re talking about seventy years of life for one of our survivors,” Rosenfeld says. “Think about that.”

MOVEMENT IS CONSTANT IN THE INTENSIVE CARE AREA OF the nursery, but Elise Beaudoing is used to the noise and activity. She’s been a nurse here for a year and a half. Alarms sound throughout the nursery as babies hooked up to various monitoring systems undergo changes in their heart or breathing rates. An X-ray technician says he’s going to turn on his machine and people scurry away from the area. A pharmacist wheels her cart through and refills the various drugs at the nurses’ stations. A cleaning person comes by to empty trash cans full of discarded IVs and preemie Pampers. But none of these people or these sounds distract Beaudoing from her task. She’s trying to put an IV into the foot of a tiny little boy. Every time she thinks she’s found a strong enough vein, the vein blows and she has to start again. She’s been at it for at least a half hour. Her patience is unwavering. This fifteen-bed intensive care unit is full, but the nurses get the word that another baby is on its way from Labor and Delivery. Right now. There’s no time to transfer a baby out; that could take hours, and they might not find a hospital willing to take a baby whose parents have no insurance, So the nurses move a rocking chair away from a space near the window at the end of the unit, notify a technician that they’ll need a portable oxygen tank, then wheel the sixteenth baby into the makeshift spot.

Some supplies, clean linens, and various boxes are wheeled by on their way to the storeroom. “Any latex gloves?” someone asks. Usually they wear gloves when touching these babies, but lately gloves haven’t been available. One nurse says she hears the whole city is out of latex gloves. Everyone’s using more of them to protect themselves from AIDS. “Has this new baby been tested for the AIDS virus?” No, but no one hesitates. They jump right in, knowing that if the baby tests positive, they are putting themselves at risk. This is a normal Friday night in Parkland’s neonatal intensive care unit, I’m told. To an observer, it is anything but normal.

The nurse-to-baby ratio in intensive care is ideally one-to-one. More often a nurse takes care of two babies if they are relatively stable. But this night, with a sixteenth baby in the unit, Elise Beaudoing is taking care of three babies. Beaudo-ing was fresh out of school when she started in the nursery, but now she’s a seasoned veteran, having lost her first baby on Sunday. “It died at 6:46 and I got here at 6:50 and had to take care of everything,” she says. “The other nurses say I’ve been really lucky to have worked this long before losing a baby. I guess that’s true. But it was really hard. I guess you just have to say the baby’s better off. It had been so sick.” Her words sound clipped, but they are filled with compassion when she talks about the pictures she keeps at home of her favorite babies-little Veronica, who is so cute, and the twins she took care of last spring. Later, on a break, she takes me down to the continuing care area of the nursery to show me one of her favorites who will be going home soon. He’s getting his bottle; Beaudoing is all smiles. These nurses deal with their feelings of loss and grief at home. Though death is certainly not foreign to this place, life is critical and ever-present. These living babies’ needs are immediate, and that pushes the memories of those who have been lost to another place and time.

I am in awe as I watch Beaudoing move swiftly from baby to baby. She assists the physician who puts a chest tube in the new baby; changes an IV and updates the attending physician on baby number two; takes vital signs and blood samples from baby number three, then mixes a potassium solution for the baby’s IV. checking the ratios several times with a calculator and getting another nurse to double-check her figures. This baby is scheduled for heart surgery tonight, so Beaudoing has an extra checklist of tasks to take care of. When the mother, who is fifteen, comes in to see her little girl before surgery, Beaudoing stops what she’s doing and pulls a rocking chair close to the baby’s bed. She wraps the child in a blanket and shows the mother how to hold it, taking care to keep all of the tubes and monitors in place. Then she shows the mother how to hold a hose that blows oxygen into the baby’s face.

Though it’s noisy in the nursery, one sound is strangely missing: the sound of babies crying. I’ve been here all day and only now do I realize it. Most of these babies can’t cry. a nurse explains, because they are too small and are on ventilators. A baby’s crying is one of the few things that throws these nurses, When a full-term baby with a heart defect or some other problem is brought into the intensive care nursery, the screams echo through the room and drive the nurses to distraction. They’re not used to their sick babies being able to cry. By the time the tiny preemies can cry, it’s nearly time to send them home.

Another alarm sounds and Beaudoing reaches up and jiggles the machinery, then gently touches the baby’s back. It starts breathing again. Sometimes they forget to breath when they fall asleep, she says calmly. Forget to breathe? I think of Shirley Mac-Laine in Terms of Endearment, jumping into her baby’s crib to shake it until it screams. Then she knows it’s breathing. 1 can’t stop watching these babies’ little chests. Oh God, this one’s not moving. Now that one’s monitor is going off. It’s like a bad dream, all of these babies forgetting to breathe.

“I know what the nurses are going through,” says Lucy1 Norris, director of nursing for the Maternal/Chi Id Health Department. “I know what it’s like to have to stop your car on the way home from work to throw up because of the stress. And 1 know about the grief you feel when there is a negative outcome with a patient and you think it could have been different had one nurse not been taking care of too many patients.”

Everyone who feels stress on the job should try to imagine the pressure these nurses deal with daily. The level of activity doesn’t slow during an eight-hour shift, and just because a nurse’s shift is finished doesn’t mean her work is over. It takes about twenty-one nurses to run this nursery. But usually, the head nurse starts with fourteen nurses scheduled. She has no choice but to find seven more nurses, and they don’t appear out of thin air. It’s Vickie Brooks’s job to get those shifts filled, and she says that means a lot of begging. “The nurses are going to give me knee pads for Christmas,” she jokes. Then she’s off to talk someone into giving up a Saturday night off.

Norris says Brooks was hired when filling the nursing schedule became nearly a full-time job for the head nurse in the Special Care Nurseries. The head nurse’s duties already included managing the nursing staff and floating through each unit of the nursery checking on very sick babies or new admissions. When the staffing comes up short. the head nurse gets assigned a couple of babies of her own-one more side effect of the nursing shortage we keep hearing about. Norris has eighty nursing positions for the Special Care Nurseries. In mid-October, she only had seventy nurses to fill those spots.

Parkland does the best with what it has to accommodate its nurses, especially in high-stress areas like neonatal ICU, Norris says. From little things like getting a mobile pharmacist to bring drug refills, to bigger issues like keeping nursing salaries competitive with private hospitals, or scheduling counseling sessions for nurses to voice their frustrations, Parkland is trying to keep those nurses happy.

It’s hard to ask a nurse who has given 150 percent for eight hours, who is completely exhausted, to keep on going for another shift. Norris says. And it’s not like these nurses are making huge salaries for their commitment. A nurse fresh out of school starts at $10 an hour. Nurses in ICU get a twenty-cent raise after finishing orientation plus another 3 percent a year above the $10 base for each year of experience. They get time and a half for overtime alter working eighty hours during a two-week period.

“But it’s a Catch-22,” Norris says. “If you don’t ask them to work overtime, then you’re going to leave somebody else shorthanded,” she says. “The stress is killing them.”

But they stay. For four and six and eight years, these nurses stay at Parkland when they know they could make more money at a private hospital where there are better benefits and fewer babies to take care of and nicer surroundings. Parkland is not new and shiny like a Medical City or a Presbyterian. It’s not uncommon to see patients walking down the halls in shackles on their way back to the county jail. In the hall on the third floor of Parkland Hospital, just outside the entrance to the Special Care Nurseries, is a bright violet light in a wire cage. Some state-of-the-art germ eliminator, I thought, impressed by the high technology. Wrong. A fly was killed by this ordinary insect zapper as I walked by it and into the nursery. No, these nurses at Parkland aren’t exactly surrounded by luxury. But then, they don’t expect to be.

“Parkland gets in your blood,’1 says Judy LeFlore, who’s been here since last January. She worked in a private hospital during a rotation in school, but as she puts it, “I went, 1 saw, and I came back.’1 LeFlore’s feelings about private hospitals are common among the nurses in the Special Care Nurseries. “I Just didn’t like it [in a private institution],” she says. “1 went to UTA and my advisor calls it fascination with the blood and guts of Parkland. And maybe the gore is part of the attraction.” The nurses at Parkland see a lot more than nurses in private hospitals just because of the sheer numbers of babies that are delivered there. And though some of the cases they see may repel the uninitiated observer, the nurses view them with curiosity-with a yearning to know more and more about this profession they love. LeFlore goes on to explain the types of cases nurses see regularly at Parkland that would rarely come up at a private hospital-the babies born with only part of a brain, for instance. There have been a couple of those lately. They live about thirty minutes, LeFlore explains, before she elaborates on her love for Parkland. “’It’s the experience you get. I like the people I work with. We get stressed with one another, but you tend to rationalize it and think, well, her baby just crashed [needed CPR]. And we do a lot of stress-release type of things.”

One of those tension-relievers, the Pre-Fair Day Food Party, happens today* but any excuse will do. Chocolate chip cookies, homemade no less, are piled all over the table in the break room. When do these people have lime to bake cookies?

LeFlore beams when she talks about her job. “In the unit there is a real cohesiveness. You never have to admit a baby by yourself. You don’t have to do anything alone. Everyone pulls together. That is just an unspoken rule. Everyone pitches in.”

AND THEN SHE’S BACK TO HER BABIES. THE parents of a baby LeFlore has taken care of for eight months now come in to see their little boy. They stop just inside the nursery to wash their hands and put on hospital gowns that visitors have to wear. LeFlore has gotten very involved with this family. The baby’s mother is twenty; his father is twenty-six, They’ve been married seven years, and they named the child after their favorite cartoon character, one of the Flintstones. This baby was the mother’s sixth pregnancy. Now, she’s pregnant: again. They had another baby in this unit a couple of years ago. but it was taken away from them when a court ruled the mother unfit. Custody is now with the step-grandfather, Earlier, custody had been given to the grandmother, but she was later proven to be a child abuser. These grandparents still live in the same household.

Though the Flintstone baby looks pretty healthy rocking in his young mother’s arms, the nurses say he will always have problems because he is chronically physically impaired. He needs constant, twenty-four-hour care, and LeFlore says it’s frustrating for trained nurses to take care of him. much less a young mother who doesn’t have a lot of money, support, or experience. Recently, LeFlore testified about the Flintstone baby at a hearing that determined whether or not he would be allowed to go home with his parents. The social worker for this nursery, Toni Ann Depina, also testified. The nurses and Depina work closely together in cases where there might be potential problems, or, as in this case* when there are problems in die past. This time, the judge decided to give the parents another chance. The nurses in the break room shake their heads in unison when they talk about it, It has been difficult to get the parents to come up to the hospital for counseling sessions to learn how to take care of their little boy. Their reasons for not coming vary. But these nurses have been here with him day in, day out. For eight months. As they have so often, they are seeing history repeated.

You’d think these nurses would have a permanent broken heart, and many days they do. The family situations of these babies are often no less than tragic. And that’s another reason these nurses stay at Parkland. They have strong feelings about social service. It. doesn’t make any difference to them whether a child has insurance or not, whether it’s from a single-parent family or one right out of a Norman Rockwell painting. The standard of care is the standard of care, though they do get more emotionally involved with some babies than others. They know they are needed and they meet the need. They make it sound very simple. Sue Storry, a head nurse in the Special Care Nurseries who’s been at Parkland for four years, says this is a key to why nurses gravitate to Parkland.

“We are dealing with people who are deserving of our care, so it makes those of us who are taking care of the babies feel needed.” Storry says. “And quite often these babies may even need us more, because often they do not have the family support that you or I would give our babies in the hospital. It’s sort of a mother effect. We think, no one wants this baby, so I’ll sort of have him.”

But Storry adds that just because the parents aren’t around doesn’t mean they don’t care. They may care too much.

“It’s hard to get close to a kid that you think might die,” Stony says. “That’s a protective measure. Their priorities are with their living children, not with the ones who may not survive.”

She says many of the parents of children in the nurseries don’t have the background to understand what is happening to their child. They get scared when they see their tiny baby filled with tubes and poked with needles, hooked up to these machines. Many of the parents have trouble getting to the hospital because they don’t have transportation, they don’t have someone to watch their children, or they can’t get off from work.

Along with the parents, these nurses can sometimes care too much. They are fiercely protective of their babies.

“That’s the thing doctors notice who come through here. They say the nurses are very protective of the babies-very,” Storry says. But, she explains, they are not protective without reason. Parkland is a teaching institution, and though that’s exciting for the nursing staff, since it keeps the hospital on the cutting edge of medical technology, there can be some drawbacks. Physicians at various stages of their education at Southwestern Medical School are rotated through the Special Care Nurseries. Some of them don’t have the background that is necessary to make snap judgments, Storry says, and may need a little extra consultation. “You don’t let those doctors play with your baby. Honey, this is my baby and if you are going to do something, you better be knowing what you are doing,” she says.

Storry admits that the nurses can be over-aggressive, but adds that she’d rather have zeal than indifference. Residents and interns from Southwestern Medical School may spend a couple of months in the Special Care Nurseries, but these nurses are there year in, year out. There is an obvious air of independence about Parkland’s nurses, and the traditional deference of nurse to doctor is absent. This is another reason why nurses stay at Parkland; they are quite autonomous. They work with the doctors, not for them. Because of that relationship, the learning curve is higher for nurses at Parkland.

SUE STORRY SITS IN HER OFFICE AND looks past me to physicians and nurses working with a baby newly admitted to the unit. This baby is full term, more than twice the size of most of the little preemies. Six people are clustered around this patient. Something is wrong with the baby’s heart and Storry is excited because they’ve figured out the problem.

“This is why you stay around here,” she says. “Nothing feels as good as knowing in your mind that you may have helped this baby. To say that I know enough about my field to help diagnose an infant and perhaps help save its life-that is the ultimate goal of my career.”

Storry begins to explain to me just how this nursery works, and works so well, but her attention keeps returning to the baby with the heart problem. These babies-the ones that appear so big and healthy, but may not live because of some congenital defect or because of a delivery problem-are truly devastating, Storry says. She is pregnant with her second child and this is the kind of baby that scares her.

And, Storry says, it never fails that the sickest babies in the unit have the nicest families. This baby, this heart baby, as she calls it, is one of those. The nurses call it the Murphy’s Law of the nursery.

And Murphy’s Law is in effect this Friday night 1 spend at Parkland. One of the tiniest babies isn’t responding to treatment. Its little head is swollen out of proportion with its body from bleeding in the brain. The chances of survival are growing slim; if it lives, it will probably be severely mentally impaired. The mother and father are a young couple who planned for this baby. It just came too soon. The husband looks intently at the doctors. He hangs on their every word. The mother stares blankly past her child and the physicians who spell out her fate, Tears streaming down her face, she mumbles about making funeral plans. In the very next breath she says she can’t give up hope. She blows her baby a kiss. The father says he’s working the night shift nearby. He can get to the hospital in a few minutes.

Earlier, Sue Storry joked that she wouldn’t have her baby at Parkland. But now she unconsciously lays her hand across her stomach and as she talks about her own baby, her voice becomes impassioned.

“I think Parkland has gotten such a bad name in the public eye as the hellhole of Dallas when in fact, it is not,” Storry says.

Parkland is definitely lacking the pretty surroundings and extra comforts of a private hospital. But those kinds of things only count when a patient is on the mend, Storry says. When your life is on the line, when you need critical care, it doesn’t really matter what color the curtains are. No, Storry’s not planning to have her baby at Parkland, but what if something went wrong and her infant needed the kind of attention she gives the babies in this nursery every day?

“I’ll be very honest with you,” Storry says. “If my baby were sick, I’d want it here.”

Related Articles

Hot Properties

Hot Property: An Architectural Gem You’ve Probably Driven By But Didn’t Know Was There

It's hidden in plain sight.

By Jessica Otte

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert