WHEN I SQUENCH my eyes and picture the lakewood Yacht Club. RIP. cap’n John is the first image up on my mental stereopticon. With his great, flowing beard and long, scraggly hair the color of old plumbing, he was, to me, as much a part of the place as the acrid smell of stale beer and the faded press photos lining the beaded walls.

John looked like the ancient mariner or some medieval lithographer’s idea of a cruel and angry God, or Howard Hughes in his hermit phase, He wasn’t angry, thpugh. He was gentle and droll. Instead of a booming voice, he spoke in a high twang that seeped through his whiskers like dark, warm molasses. He always wore a Greek fisherman’s cap: I guess that was why we called him Cap’n. The one time I saw him take it off, I was amazed to discover that above the tangled hair, the top of his head was as bald and smooth as a brandy snifter.

Late each afternoon, about the time the fading sun softened the ugliness of the safeWay supermarket and Centennial liquor store across Abrams Road, John hobbled into the Yacht Club. He dragged his gimpy leg and leuned on his cane, the one with the bicycle horn (aped to the crook so he could beep out his wishes like Clarabel the Clown. Usually, he carried his camera, an expensive 35-millimeter job with a motor drive and strobe. He snapped pictures of attractive women, and they smiled and kissed him on the cheek. When the film came back from the drugstore, he passed out prints to the people pictured or tacked his photos to the wall. It was the way he took his pleasure.

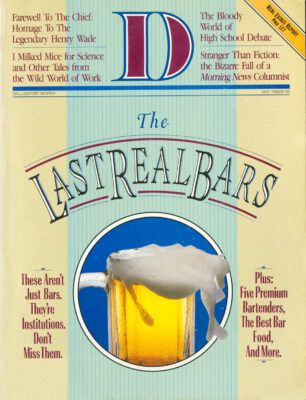

I never saw the Cap’n take a drink of alcohol, though alcohol was what the Yacht Club was in business to sell. Bartenders kept him supplied with hot. bitter coffee. I don’t think he ever paid for it, but no one seemed to care. John belonged to the Lakewood Yacht Club; the coffee was his due. When I say that the Cap’n belonged, I mean it in a broad, cosmological sense: he fit in; he was appropriate: his presence helped define the place. It was not possible to “belong”” to the LYC in any conventional way. Despite the name, the Yacht Club was not a club with dues and rites of initiation. Nor was it within a day’s walk of the nearest yacht. Proprietor Tom Stephenson simply indulged a penchant for fanciful names. At various times. Stephenson also owned the Greenville Avenue Country! Club, which was not a country club, and the Lakewood Polo and Hunt Club, which wasn’t much of anything.

No, the Yacht Club was not pretentious. It was simply a neighborhood bar Located, until it closed in 1983. in a faceless strip shopping center that shambled up Abrams from the intersection with Gaston Avenue, it was small, dark, and more than a little dingy. It boasted a fine, ornate back bar, a relic of a time when even saloons honored craftsmanship, but the rest of the furnishings were as motley an assortment of tattered vinyl stools and rickety old tables, as you’ll see. A tiny, grease-encrusted kit-chen reluctantly yielded hamburgers, homemade potato chips, and the worst nachos ever conceived. Young bartenders, mostly SMU refugees, managed the occa-sional pina colada, but the regular drinks were whiskey and beer.

I don’t mean to slight the Yacht Club when I say it was simply a neighborhood bar. I intend the description as a compliment. Anyone who has spent time in England or Ireland or in the grittier cities of this country-Milwaukee, St. Louis, Detroit-understands that a neighborhood bar is an important urban institution, a civilizing, soothing influence in a sandpaprr world, It is a sucial center, a bosom of refuge, a demo-cratic place where a man like Cap’n John stands next to a bank president or a famous writer and they toss down a brew together.

“A neighborhood bar is a place to drink and talk,” says Dallas writer Jim Atkinson, who is studying taverns for a book tentatively entitled The View from Nowhere: An American Bar Journal, due from Harper & Row nest year. ’”It is not a place to eat, be seen, or hustle women. All the regulars know one another but rarely see each other outside the confines of the bar. They are people of diverse backgrounds who might not have much in common anywhere else.”

Yacht Club regulars were, indeed, a diverse group. Some you have heard of; former city councilman Max Goldblatt, slate Rep. Paul Ragsdale, Dallas Morning News columnist John Anders, Most were less notorious, like Bill McCartney, who manufactures college jewelry, and Mack McGlothlin, who imports stuffed piranha from the Amazon basin. Highland Park banker Darrell Wootton was a regular, as were dermatologist Russ Griffith, criminal defense attorney Charles Tessmer, and sales vice-president Chuck Willingharn. They nibbed shoulders with a nurse, a poet, a Saks Fifth Avenue clerk, an architecture student, a carpel salesman, a major league baseball umpire, a steelworker, a stockbroker, several schoolteachers, and a women’s amateur soccer team. And, of course, there was Cap’n John.

KRLD radio commentator Alex Burton, a self-proclaimed international expert on all manner of watering holes, asserts, ,”A neighborhood bar is not only a bar within a neighborhood, it is a neighborhood with-in a bar,” And so it was at (he Yacht Club- a cross section of the community. as they say. The regular crowd was an inspired concoction, a rich, savory social stew.

Tetchnically speaking, the Lakewoood Yacht Club was not in Lakewood. From its front door, you could barely glimpse the elegant, tree-shaded homes that designated Lakewood when some developer platted the land sixty years ago. True, the parking lot of the Lakewood Country Club (which is, in fact, a country club) loomed across the way, but Cap’n John’s bar recognized no bond to caviar and Cadillacs.

In a larger sense, though, the Yacht Club helped stitch together disparate sectors to create (he bigger neighborhood now loosely known as Lakewood, People from junius Heights, Abrams-Brookside. the Bel-mont area, Hollywood Heights-in fact. all the haphazard clumps of houses, apartments, and condominiums from Mun-ger Place to the M Streets-found a locus in the LYC. As each area began to claw its way batik, from the East Dallas decline in the Sixties and early Seventies, residents discovered common interests and problems as they encountered each other in the LYC. In its modest way, the Yacht Club Was a catalyst for a growing community.

Then it closed. In a pit -putt’ with the landlord, Stephenson lost his lease. He auctioned off the photos and the unsteady tables with tobacco leaves preserved under their glass tops. He took down the moth-eaten tapestry from, over the door and ripped up the hardwood floor, Finally, the weathered wooden sign was toppled and the Yacht Cluh closed for good.

Jim Atkinson believes the neidiborhood bar is a dying institution throughout the country. With more transient populatioiis and the homogenization television brings, he says, Americans lose the sense of neigh-borhood-as-village that nurtures these tiny pubs They turn to taverns like Bennigan’s, which are comfortably familiar, even in strange cities and which offer the added advantage of affirming their patrons’ upscale achievement. Alternatively, they relax after work in joints catering to people just like themselves. Attorneys stop in lawyers’ lounges. truckers hit the honky-tonks. No surprises either way.

In Dallas, though, the tradition of the bar asmelting pot lived sickly and died early. Neighborhood bars never dotted the corners as they do in most large cities! Folks here never really got into the habit of loosening their collars and winding down with a beer or two. Why? One reason, of course, is that Dallas has vert’ few true neighborhoods. It is a new city. Many- of its residents have come from elsewhere in just the past ten years. Perhaps there has not been enough time for neighborhoods to grow.

Mike Carr has operated several Dallas neighbor-hood bars, including, most recently, The Quiet Man on Knox Street. From his ex-perience, Carr concludes that the emphasis on busi-ness in Dallas works against the neighborhood bar. “Everybody here uses the cocktail hour as an exten-sion of the business day,” Carr says, “People stop for a drink in places where they can make contacts and close deals. No one seems to enjoy socializing for its own sake.”

Tom Stephenson believes Dallas liquor laws are largely at fault. That most of Dallas is dry means little bars cannot spring up in residential areas as they do in; other cities. It also means, Stephenson says,, that the few parts of town in which alcohol can be free-ly sold tend to become entertainment districts instead of neighborhoods. No doubt, residents along the streets near Greenville Avenue know exactly what he means.

It is partly because of the patchwork of dry areas created by local option referenda that Stepherison, Carr, restaurateur Gene Street, and others con-tend the Yacht Club was the last Dallas neighborhood bar. Parking restrictions, in-dteasing!afcdhol taxes, and extraordinary rents for even modest commercial space also work against the kind of small, cozy den in which Cap’n John was comfortable.

“I’d like to open another place something like the Yacht Club.” says Stephenson. “But I’m not sure it is ever go-ing to be possible again to operate a small bar where prices are reasonable and you can just talk. Buy drinks, spend money,: and get out of the way so we can collect somebody else’s money. That’s not a neigh-borhood bar.”

Jim Atkinson sees a more fundamental reason why the Yacht Club may have been the last of its breed in Dallas. A neighbor-hood bar, he says, is an organic thing. You cannot make one. There must be a social yearning. People must ache for a place! where they can step out of their business identities into more instinctively human roles. A neighborhood bar grows up. he! says, only when the community needs it.

To some extent, the Lakewood area has matured in recent years. Partly with the help of the old Yacht Club, those of us who live there have come to identify with our neighborhood and be proud of it. Perhaps our need has passed.

But I see some of the LYC regulars every now and then. They have scattered to other spots, each of which caters to a segment of the whole. A few meet amid the noise and foul: food smells of an in-hospital; anteroom in an El Chico restaurant. Sme stop for a drink in a joint failed Schooners where, late at night, incessant modern rock drowns conversation. Some frequent George Wesby’s, a pleasant Irish; tavern blocks from the nearest neighborhood Wherever three or four of that crowd find themselves together, they reminisce about the Yacht Club.

“I sure wish somebody would open another bar like that,’’ someone always says. And the talk turns to neighborhood friends we don’t see anymore, Inev-itably. before we break up, not to chance together again for several weeks or months, one of us re-merabers our favorite Yacht Club character. Then we puzzle a moment, “I won-der what ever happened to old Cap’n John.”

THE BEST BAR FOOD IN TOWN-BAR NONE

THOSE SINGLE-MINDED soils who believe that even peanuts are extraneous to the bar experience can skip on to the next martini, and good luck. If. however, you have concluded from painful experience that drinking without eating is like shooting yourself from a cannon-in that it gets you up there in a hurry, but provides no net for the trip down-read on.

Taking it from the top. the classiest bar food in town, bar none, is served at Routh Street Cafe. Those who want to have a full-scale dinner at Routh Street must make reservations and pay forty-two dollars per person. There is, however, another side-door option: the impetuous drinker can waltz in. sit at or near the bar, and order by the course from Routh Street’s fixed-price menu.

The Mansion on Turtle Creek’sbar has a ten-item menu of itsown-small enough to be perfectly executed every time, yet largeenough to hold the interest ofregulars. The highlights includeginger-duck spring rolls with plumsauce and sesame chicken.

Over at the Hotel Crescent Court, the Mansion’s new corporate sibling, one can order from Beau Nash’s regular menu at the bar. The post-modern pizzas-especially the pheasant sausage and the smoked salmon-are highly recommended.

On a less rarefied level, Zanzibar, Andrew’s, and Dick’s last Resort are good bets when you’re seeking extra-liquid benefits in a bar. Zan-zibar offers an imaginative complement of yuppified pastas and sandwiches to accompany the ex-tensive selection of wines available by the glass. Andrew’s has a full- scale casual menu, from burgers to black bean soup. Everything is respectable, but the house-made cheese crackers are peerless. They make perfect partners to a Scotch and soda. Beer seems to be the beverage of choice for most patrons at Dick’s List Resort, and the top-quality, limited menu (chicken, ribs, shrimp, crabs, and catfish) was designed to do justice to it.

-Liz Logan

HEY, BARTENDER!

Five mixmasters who pour double shots of wit and wisdom.

by Bart Barker

VAUGHN VALENTINI Day Tripper

Plus ours

When Hank Williams Jr. sings “Family Tradition” and blames everything on his old man’s hundred-proof ways, Vaughn Valentini must think they’re playin his song. His grandparents were bootleggers in New Mexico during Prohibition. After booze went legal in 1935, his family opened the first bar in the state.

Valentini. who moved to Dallas in 1980. worked a series of strip dubs as a bartender am) was frequently his own bouncer when good ol’ boys went bad. After five years on the night shift, he switched to days-and that’s tall cotton for him. He’s much happier with the downtown businessmen and lawyers who come in during his shift. “When I worked topless bars I’d come on duty and start picking out who I’d have to throw out that evening,” he says. “You take a big cut in tips working days, but it’s a quiet croud.”

STEVE HARRIS, Human Blur

The Bullington Point

Maybe it’s because Steve Harris is a Vietnam vet. Maybe he thinks he’s still under fire. Whatever the reason, he tends bar like Bugs Bunny on speed tied to a string of Chinese firecrackers. If he stands still long enough, you get a glimpse of a short guy with Rocky the Flying Squirrel spectacles, and they’re appropriate He rockets around behind the bar and sometimes you hear more of him than you see-glasses clinking, spigots spewing, bottles clanking, and a barrage of rapid-fire chatter flying in all directions.

If you have good peripheral vision, you can actually see Harris doing all this: simultaneously filling a pitcher of beer, loading a cocktail glass with ice, flipping the ice scoop so that it lands point down-and all the while, his mouth never misses a beat.

Says one customer watching the show: “You oughta see him when he’s busy.”

But then you probably couldn’t see him at all.

LOUIS CANELAKES, Prince Of Pour

Joe Miller’s

Anybody who’s been pubcrawling in Dallas any time at all ?ill tell you: it’s hard to beat Louie Canelakes for brain-bombing libations and ad libs that can kill at twenty paces. He’s considered by many to be one of the city’s absolute greats and is destined, with the passage of time, to become not just a great bartender but maybe a great bar owner, perhaps as legendary as his “adopted” father, the late Joe Miller.

Louie is, like Miller, snide, sarcastic, incisive, ill-tempered, and blunt. He is also, like Miller, a regular Boy Scout at the bottom line-kind, sensitive, intelligent, trustworthy.

Wit? El Greco from Chicago doesn’t just tell jokes: be makes up a fair percentage of the bowlers you’ll be hearing around town tomorrow night.

Killer cocktails? If he likes you, he’ll pour you an incredibly stiff drink and take your money. If he doesn’t like you, he’ll pour you an incredibly stiff drink and take your money all the more gladly.

Just remember the big rule, enacted under Miller but, still in full force: “No foo-foo drinks. Nothin’ with a blender. Nothin’ with an umbrella. Hey, dis ain’t no Baskin-Robbins.”

THOMAS RITTINGER, Class Act

The Mansion on Turtle Creek

One of the marks of a good bartender is whether he can overcome a tough venue. Hats off to Thomas (not Tom or Tommy) Rittinger. The Mansion is a tough venue, when you think about it. It’s pricey, formal, and a bit intimidating even to those who can afford it-and it’s over-pricey, snooty, and overdressed to tin would-be and not-so-rich who show up there anyway.

But Thorns is the great leveler, master of the trick of treating everybody the same. He neither grovels to big bucks nor condescends to little ones.

Not too long ago this guy who looked as though he’d just fallen off a pumpkin truck wandered into the Mansion in search of refreshments. Thomas smiled at the guy-me, actually-and said, “I’m sorry I have to do this, sir, but we require a tie, so while you’re deciding what you want to drink, I’ll get you one.” If you can pull this off as smoothly as he did and even make of that person a friend, then apply for his job. Dat’s. as dey say. real class.

THE DEBONAIR DANCELAND POST-DEBS

Debonair Danceland

There are female bartenders in Dallas, sure, but tending bar is often a tough trade for a woman. First of all, the customers are often drunk and almost always mouthy. Second, there’s often the problem of finding all-night child care. Management isn’t always sympathetic.

The exception is the Debonair Danceland. Given some latitude on hours and occasional absences by their manager, the eight women here may be among the friendliest bartenders in town. But you have to speak Texan to understand them. A sample:

“Hay-you much furra ba-yur?” (How much for a beer?)

“Siviny say-unts.” (Seventy cents.)

“An hay-yow much furra shot ana Coke?” (Now you try it.)

“Be thray-ten for thuh shot and a dollursiviny-fi fur thuh Coke.” (Good, good.)

“Ha-yull, Ah’ll taka ba-yur.” (Hell, I’ll take a beer.)

Says Myra Zarate, an old potash miner’s daughter who was married for a while to an Indian (“that’s Indian like ’woo-woo,’ not one of them Eastern guys”): “It’s an easy atmosphere here, almost like a family. But anytime yon got alkyholic beverages an’ men, you’re gonna have some bandits.”

Bartender Jackie Gregory has battled cancer for seven years, but has yet to have a problem getting off work for treatment. Women with child-care problems get a similarly sympathetic hearing from manager George Cornue. “Good Lord,” he says, “people are gonna have problems, and we need people.” The result is a happy bartender, which means happy customers.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte