IN BETWEEN monster bites of green fettuccine. The Guy Who Was In The Godfather was telling me about the next megabuck hit movie to be filmed in Texas.

“I’m not at liberty to reveal all the details at this time,” he said, leaning into his lunch so heartily that a gold neck chain dangled dangerously close to his pasta. He was skinny as a noodle, and his face had the heavy-lidded seriousness of a Brooklyn street kid who’s been beaten up by his brothers one too many times. Coppola liked his face, he’d told me. That’s how he got the Godfather part. A good face, all his friends agreed. “The camera loves this face.”

“Okay, I’ll tell you this much,” he said, “but you’ve got to protect me, because you know how Hollywood will steal you blind. You know, the main thing we got is this story, so we don’t reveal it to too many people.”

He nodded toward his cohort, a fellow Italian from Brooklyn who had already hugged me twice and pumped my hand like a tire jack. “Go ahead, Johnny. Go ahead and tell him the story. It’s okay. Don’t worry about it.”

They looked at the man they had introduced as “our Texas connection’-a realtor from Abilene. He gave the high sign for my security clearance.

“Okay,” said Johnny, “here’s what it is. I’m the star. I’m a kid from Brooklyn that wants to be an actor, but nobody’ll give me a shot, right? So the only way I can get any respect is to fight all the time. So what happens? I started winning Fights, right, and pretty soon I got a title shot. Only, see, once I start getting publicity on the fight circuit, this director gives me a part in a movie. Big Hollywood movie. Only everybody says, ’He’s a bum, no way he can act,’ and so I make the movie and-bingo-I get nominated for the Academy Award. So then the title shot comes up, against the Heavyweight Champion of the World. I ain’t got a chance, right? He outweighs me twenty pounds. But here’s the deal-the fight is on the same night as the Academy Awards ceremonies.”

Johnny paused for a moment and chewed on his garlic toast.

“I’m sorry, that’s all I can tell you. I really don’t want to reveal the ending.”

The three would-be movie tycoons all looked at me for a reaction.

’Well,” said Johnny’s sidekick, “what do you think?”

“Interesting story,” I said, rather lamely.

“What did I tell you? And I want you to know something else, John, because I want you to tell Texas this. When we make this movie, and we’re up there on the podium in Hollywood accepting the Academy Award, do you know what we’re gonna say?”

I was afraid to guess.

” ’Thank you, Dallas.’ That’s what we’re gonna say. ’Thank you, Dallas, for making it all possible.’”

All they needed now, they concluded after the elaborate presentation, was somebody in Dallas to put up $10 million. The Oscar was practically in the bag.

It took me another hour or so to escape from the Brooklyn tycoons-they followed me into the parking lot and insisted on taking a picture of all of us together, embracing shoulder-to-shoulder, heedless of the danger of impaling ourselves on cheap men’s jewelry-but I finally got beyond striking distance and breathed a sigh of.. .not so much relief as deja vu. This, more often than not, is what it meant to report on the Texas film industry.

THAT WAS IN 1983, almost exacdy a decade after Texas started calling itself the “Third Coast,” at a time when it seemed we were closer to becoming the Third Ghost, the land of perpetually unfulfilled promises. Trammell Crow’s Dallas Communications Complex had gone through two troubled regimes in quick succession, and most of its stage time was still unclaimed. Joe Camp, the creator of Benji and founder of the Dallas feature-film industry, had a short-lived, ill-fated TV series and two private offerings that fizzled in the proposal stage. Bill Tanne-bring, the successful commercial producer, attempted to break into feature production with an ambitious eight-film co-production agreement with an Australian producer-but after the first shoot, a still unreleased film called Voyeur, Tannebring and the Australian fell out amid mutual charges of betrayal. The California Legislature held a series of hearings designed to stop “runaway production”-a move widely perceived as an attempt to stop Texas and Florida, the two states rapidly making inroads into Hollywood’s pocketbook, And finally, to add insult to injury, the most successful of “our” films. Terms of Endearment, won the 1983 Academy Award for Best Picture, but when director James Brooks made his acceptance speech, he went out of his way to make people understand it was a Hollywood film after all. He effusively thanked Paramount, the studio that had refused to make the movie until Texas producer Martin Jurow whittled the budget down to an acceptable level, scouted the Texas locations, and saved Brooks’ adaptation of Texan Larry McMurtry’s novel. (You could almost say the same thing about Places in the Heart, Robert Benton’s semi-autobiographical melodrama about his youth in Waxahachie, except, despite Benton’s “roots,” Places was more of an exaggerated stereotype than Terms and really had very little to do with the cultural history of the state.)

It seemed, in short, that Texas was destined to be the repository for a) movies Hollywood didn’t really want to make (like Terms), but would take credit for in the event they became successful, b) movies that were so cheap they couldn’t be made anywhere else (a movie called Mongrel comes to mind here), and c) movies that wouldn’t be made at all except for the widespread notion that Texans had fat pockets and short memories. (The guys from Brooklyn are the best example, but you might also include Peter Bogdanovich, who offered a three-picture deal here in 1983, a deal that was actually not bad on paper except for one detail-Bogdanovich took $1 million per film as his personal fee. Dallas investors, after they stopped retching, showed Bogdanovich the state line-and privately felt vindicated when he declared bankruptcy last year.)

All of this flotsam and jetsam of the checkered immediate past, though, is but prelude to the glad tidings-and I have to be careful here, because this has been said before-of a New Order of Things. Finally, this year, the Third Coast pioneers are starting to establish permanent settlements. This winter, for example, there have already been six Dallas premieres of local projects-The Trip to Bountiful, directed by Texan Peter Masterson, written by our unofficial screenwriter laureate, Horton Foote, partly financed by the FilmDallas fund, and almost certain to be an Oscar contender; Iron Eagle, a youth-oriented crowd-pleaser, with daring flying stunts shot with the assistance of the Israeli Air Force, financed by local businessman Max Williams and his U.S. Equity Corp. as the first in a series of “all-American” action movies that will have budgets totaling $100 million; Pray For Death, one of the best martial-arts pictures in recent years, produced by London-based Arab businessmen and a Los Angeles production company, starring Japanese samurai star Sho Kosugi and distributed by American Distribution Group, which is controlled by Dallas oilman Al G. Hill Jr.; The Dirt Bike Kid, a FilmDallas G-rated fentasy for children that’s still searching for a marketing campaign; Papa Was a Preacher, a G-rated period piece based on a true Texas story, the latest from Terms of Endearment producer Martin Jurow; and Getting Even, Al Hill’s thriller about a sadistic businessman who tries to blow up Dallas by planting a chemical-warfare bomb atop Reunion Tower, featuring a climactic helicopter chase through the Trinity River bottoms.

Six very different projects, but with one important difference from so-called “Texas projects” of the past.

“The best way to describe it,” says Sam Grogg, president of FilmDallas Inc., “is informed active capital. For the first time, we’re doing more than just contributing our money to someone else’s project. We’ve taken the mystery out of Hollywood. We’ve learned the financial details of the business. And we’re finally making our movies our way.”

“The bad reputation the film industry has in Texas,” says Al Hill, who got involved in two box office disappointments before he fastened on a formula he likes, “is well-earned and well-deserved. The image of movie investments here has always been a bunch of ripoff artists-a fat guy with a cigar, riding in a limo, with three girls on his arms, a drink in each hand-in other words, waste is the image. For most people here, it’s an embarrassment to be involved in a film project. They’ll say to you, ’Oh, yeah, I’ll invest, but don’t tell anyone. ’So we’re slowly and surely starting to change that. People trust me, because they know that all of my businesses are run to make money, that I’ll use my staff top to bottom, and that everything will be done on a businesslike basis. But very few people from the outside are going to get that trust.”

Taking the flakiness out of the filmmaking process-which, after all, is the most corrupt and unwieldy art form this side of grand opera-has been a long time coming. The Dallas film industry actually dates from 1915, the year a studio was established here to turn out industrial films for the cotton and banking industries. Today there are 200 some-odd film companies in the Dallas area, all descendants of those pioneer industrial filmmakers, although the operative term today is “corporate communications films.” Then after World War II, radio entrepreneur Gordon McLendon founded a recording industry as well, mostly to turn out jingles for his far-flung empire of Liberty Mutual Network stations, and that investment led to a loose association of Texas recording studios, most of them in Dallas and Austin, that runs a distant second to Nashville’s Music Row in its volume of recording work. At the same time, a Midwestern fashion industry began to grow up around the Apparel Mart, built in the early Sixties, and out of that came a network of talent agencies to provide actors and casting services for the commercial TV producers. The final element was Karl Hoblitzelle’s Interstate Theaters, the many-tentacled Dallas monopoly that controlled movie exhibition in almost every city in the Southwest before it was broken up by the Justice Department in the early Fifties. Hoblitzelle cultivated extremely close ties to the seven major Hollywood studios (all of which still maintain large regional offices in Dallas) and could sometimes exert enormous influence over what films were made and how they were premiered and marketed in Texas.

WHAT ALL OF this amounts to is an infrastructure, the intricate, cumbersome machinery that must exist for any large-scale production. Still, prior to the Seventies, most of the movies made in Texas were financed and produced by mainstream Hollywood filmmakers, usually major studios. As a rule they were either Westerns (Viva Zapata!, The Texans, The Alamo) or films with screenplays demanding Texas locations (Air Cadet, Giant, State Fair, Bonnie and Clyde). The only exception was a series of exploitation films made in Dallas in the late Fifties (Rock, Baby, Rock It, The Giant Gila Monster, Attack of the Killer Shrews), several of which were financed by Gordon McLendon to provide inexpensive products for his chain of Texas drive-ins. (Several of these films, previously believed lost, were recently rediscovered in The Tyler, Texas Film Collection, currently being restored and preserved by Bill Jones at SMU’s Southwest Film/Video Archive.)

By the early Seventies Texas had become known, like Italy in the Fifties and Yugoslavia in the Sixties, as a place you could go to make a cheap picture. For a while you could even film secretly, without letting the guilds and crafts unions know where you were, and for a while after that you could get “quiet” low-budget deals from local negotiators for the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), as well as the Teamsters, who control most of the transport functions of a movie company on location. This is no longer true (although the myth of non-union moviemaking in Texas still persists), but it is true that films can be made for up to 30 percent less in Texas than in California or New York. In order to preserve this advantage, the Texas industry recently formed a lobbying organization-the Motion Picture Producers of Texas-to make sure the Legislature protects the favorable filming climate. Joe Camp, the Dallas producer/director who made the first unqualified Texas blockbuster (Benji in 1973), heads the council.

Still, you can have all the crews, producers, and artists in the world, and you still don’t have a film industry without investment capital-long our Achilles’ heel in Texas. The most common complaint of would-be film producers here is that the Texas investment community is too dim-witted to see the great opportunities in moviemaking (translation: “they won’t invest in my film”). But, in fact, the op-: posite seems to be the case. Especially in the past five years, there has been more capital available in Dallas and Houston for high-risk film projects than almost anywhere else in America. Trammell Crow spent $35 million on his state-of-the-art film studio and office complex built on little more than faith-faith that the movie industry would grow as rapidly as the fashion industry did after he constructed the Apparel Mart in 1963. The Hunt brothers, Nelson Bunker and William Herbert, invested some $80 million in Sherwood Productions (WarGames, Mr. Mom), the company formed by David Begelman after his admissions of check forgery lost him his job as head of Columbia and then MGM. A consortium of Houston investors provided almost all the capita! for the $20 million Superman III. Abilene oilman Jack Cox put up all the money for Last Plane Out, a pro-Somoza film about the Nicaraguan revolution that had a limited release. Gordon McLendon continued to make independent production deals with the major studios, his latest project being the 1981 international hit Victory. The Bass brothers of Fort Worth even went so far as to purchase controlling interest in an entire studio (Disney) and revive its once ailing fortunes. In fact, by some estimates as much as $350 million in Texas money is pumped into the film industry each year, must of it by the same gambling spirits who speculate in oil drilling and commercial real estate ventures.

What, then, is the difference between today and 1983, when “film” was still a dirty word to all but a few entrepreneurs?

Two case studies-of the highly publicized Film-Dallas fund, and the lower-profile film enterprises of Al Hill-illustrate best what has happened.

FilmDallas, funded in late 1984 and early 1985, was the brainchild of Sam Grogg, former head of the USA Film Festival and erstwhile protégé of George Stevens Jr., the imperious father superior of the American Film Institute. (It was Stevens’ father who directed the ultimate Texas movie-Giant.) Grogg knew film (in a distant past life he was an assistant professor at Bowling Green State University), but more important, he knew the politics of film. With his partners, finance attorney Richard Kneipper and investment and mortgage banker Joel T. Williams HI, Grogg set out to raise $5 million for a venture-capital fund that could spread its money among several films, instead of just one, and thereby maintain a diversified portfolio. It was not much money to ask for-the average Hollywood budget is now around $13.5 million-but it was still more money than he could raise from skeptical, oft-burned Dallas investors. After scaling back the offering, the first FilmDallas fund was finally capitalized at $2.4 million.

What’s remarkable about the fund is that, with such a small amount of money, Grogg was then able to generate such a large volume of excitement. Scarcely a week passed that FilmDallas wasn’t in the news, either making a new deal, starting a new film, or winning a new award.

“The secret to that,” says Grogg, “was that we made a concerted effort to invest in so-called critics’ films. Even if the films weren’t giant commercial successes, we had a good idea that they would be popular with the critics-and therefore written about, talked about. They would establish credentials for us. And that, by and large, is what happened,”

The rules of the fund are these:

1. FilmDallas invests only in films budgeted at $2 million or less. In today’s market, this is about as low as budgets ever go.

2. The fund participates only when its ownershipis between 25 percent and 50 percent. This is to makesure the have a measure of control over the production, but without total risk.

3. They never invest more than $500,000 in anyone film.

4. They never invest in any project that doesn’thave a guaranteed distribution contract. This is moredifficult than it sounds, because there are only aboutfifteen U.S. companies that have the sophisticated apparatus needed to get a film released on America’smovie screens.

“We’ve published these rules,” says Grogg, “and we’ve made them known to everyone, and we never depart from them, but every day someone calls with a project that doesn’t fit the formula. They don’t believe it. They think that for their project we’ll bend the rules a little. But it just doesn’t work that way. We established these rules because, at the point we are right now, this is the only way we can have a reasonable chance of returning a profit.”

Here’s how the formula has fared so far:

Choose Me: This moody jazz essay about modern relationships, a stylish, off-beat film by Alan Rudolph, was already playing in two theaters (one in Seattle, one in Los Angeles) when Grogg first saw it. But Island Alive, the film’s small New York distributor, was cash-poor and needed an infusion of capital to widen the release pattern and take advantage of the film’s great reviews. FilmDallas put up a half million dollars- $300,000 for prints and advertising, $200,000 for an equity position in the film-but later regretted the deal. Even though the film went on to wide national acclaim and had long runs in art houses, FilmDallas still hasn’t broken even on its investment, because Grogg had to wait in line for payment behind other investors.

The Trip to Bountiful: Trying to duplicate the success of Tender Mercies, which won the 1984 Oscar for Texas screenwriter Horlon Foote, and trying to avoid the failure of 1918, last year’s stagebound, stillborn adaptation of a Horton Foote play, Grogg signed on for the next Foote project, to be directed by Foote’s cousin, Peter Masterson, of Best little Whorehouse fame. This time FilmDallas put up $500,000 of the $1.6 million budget, and Grogg also put together a consortium of investors in Dallas, Austin, and London to provide the rest of the financing. “This is something we’re probably going to be doing more and more,” he says. “We’re the bellwether. We decide what project should be targeted. And then the other money follows. So we gain more control over the production by being the agency of getting that other money. It’s not something I enjoy doing-it’s a pain, really-but it’s best for the fund right now.” In this case the secondary investors are more than happy, with Bountiful almost certain to figure in the Oscar race, and with Geraldine Page’s performance being hailed as the finest of her career. Again, this was a “critic’s film” that brought notoriety to the fund out of all proportion to the small investment.

The Dirt Bike Kid: This Disneyesque family comedy about a magical motorbike, made in partnership with Julie Corman (wife of exploitation king Roger Corman), may turn out to be the one investment that can’t be saved. FilmDallas owns a third of it, by virtue of putting up $500,000 of the $1.5 million budget, but initial engagements at Christmas were disastrous. Concorde Cinema Group, Corman’s distribution company, is trying to decide whether to spend more money on it (for a new ad campaign) or simply to “play it off (take bookings wherever they turn up, spend no money on it, and go on to the next picture). “The problem is they don’t know how to market it,” says Grogg.

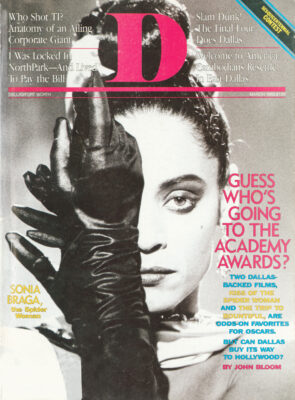

Kiss of the Spider Woman: This strange film, starring Sonia Braga, William Hurt, and Raul Julia, set in a Brazilian jail cell where a homosexual and a political prisoner try to come to terms with each other, was a hit at the Cannes Film Festival and cost $1.5 million just for U.S. theatrical and videocassette rights, FilmDallas put up a third of that and, based on the film’s critical and box office success around the country, it should continue to do well.

Total expenditure for FilmDallas: $2 million. Total return? “By the end of the first quarter of the year, we hope to have returns of$l million,” says Grogg. “That will put us 50 percent home.”

Results: inconclusive. All four films were types that have no possibility of becoming blockbusters-even if everything goes into the black, the profit will be modest-but nobody will feel “burned” by these deals. That alone separates this venture from the hundreds that have come before. And enough of the investors are satisfied that Grogg and party will be offering FilmDallas II this spring. Grogg expects their first project to be a Jane Alexander drama called Square Dance.

AL HILL, WHOSE office is so high in Thanksgiving Tower that you have to take three elevators to get there, says he’s not interested in the FilmDallas formula (even though he’s one of the original investors).

“I’m not interested in something that promises a 20 percent return,” he says, revealing his oil driller’s instincts. “Or even a 30 percent return. Or even 50 percent. That’s fine if that’s all we can get. I’ll take it. But I’m more interested in structuring deals that have a much higher upside potential. If you invest in the right film, the earnings are virtually unlimited.”

Hill has been intently studying the film industry for six years now. He spends about two hours a day reading film industry trade and financial publications and has used his contacts in the tennis world (he”s been president of World Championship Tennis for seventeen years) to open doors into the entertainment world. In fact, his first four projects, beginning in 1980, were done in partnership with professional tennis players Vijay Amritraj and his brother, Ashok. Here’s how he fared:

The Magical World of Gigi: If you’ve never heard of this fifty-two-week cartoon series, it’s because it’s played everywhere in the world except the United States. “That was by design,” Hill says. “The American children’s market is too sophisticated and specialized to do anything on a low budget.” But the series, made in partnership with a Japanese TV station and a company called Harmony Gold in Los Angeles, had the highest ratings in Japan.

Fleshburn: This thriller, set in the Mojave Desert, starred Dallas’ Steve Kanaly. Hill and the Amritraj brothers put up the money. It bombed in a very limited release. The film never played Dallas.

School Spirit: This low-budget ’Animal House” -type comedy about a college student who’s run down by a truck but returns as a ghost played for about five minutes. It was co-produced with Roger Corman.

Nine Deaths of the Ninja: Shot in the Philippines with hot Japanese star Sho Kosugi, this picture was “embarrassing,1’ according to Hill, but still did $14 million worth of business in its first four months of release. “All that told us was that the market for martial arts is definitely there,” says Hill, “and it’s very, very strong.”

After the disappointing results of those projects. Hill parted company with the Am-rilrajes, brought in one of his executives, Mike Liddle, to head his own production company, and decided to make his own films instead of investing in other people’s ideas. So Liddle developed a marketing plan.

“Mike took the elements we had available to us. looked at what the foreign market wants, what the video market wants, what the theatrical market wants, and here’s what he found. In America, you’ve got to have one or all of these elements for success:

“Great soundtracks. But it’s very expensive to buy that music.

“Elaborate special effects. Also very expensive.

“Great comedy. All the Bill Murrays and Chevy Chases and Eddie Murphys cost a. fortune.

“Sex. I’m not personally interested in making something I wouldn’t want my children to see,” Hill adds.

“Action. Cheap.

“Violence. Cheap.

“So on the low-budget film, we decided the only thing we could produce, with the potential of making substantial profit, was the action adventure. Based on all these elements, Mike wrote the story line for Hostage: Dallas’’

The title was later changed to Getting Even for American release-it had its world premiere February 25, benefiting the Dallas Arts Magnet High School-after a marketing study showed the original title had too many associations with television. Filmed in Dallas last summer on a budget of $2.25 million, the film stars Audrey Landers (chosen because she has four platinum albums in Europe and in hopes that her lead role in A Chorus Line would win more acclaim than it did), Edward Albert, and veteran arch-villain Joe Don Baker. Getting Even is filled with stunts, car wrecks, explosions, and copter chases and has very little plot to get in the way of the action. Hill calls it “a James Bond film on a low budget.” Even before its theatrical release, Hill turned down two lucrative offers for videocassette rights.

In fact, Hill got so high on Celling Even that he’s getting into the shark-inlested film distribution business. Earlier this year he hired Alan Belkin, who ran American Cinema Group for many years and launched the career of Chuck Norris. Belkin will run Hill’s Los Angeles-based American Distribution Group, which will release five to seven films a year, beginning with Pray For Death, which had its national release in January and shows signs of being one of the highest grossing martial-arts films of recent years.

“I realized last summer that film distribution is really the safest place to make money,” says Hill. “And in the future I won’t be producing any films that American Distribution Group doesn’t like. Eighty-five percent of the films that are made should never be made. People deceive themselves and think they’re making something commercial, when all they’re really doing is trying to satisfy their own egos. These films will be strictly business. And I’m in this business for the long haul.”

Even three years ago, Getting Even and The Trip to Bountiful could never have been made in Dallas. At last, perhaps, we’ve taken the flake out of film investment.

“We’re not hanging a big bag of money outside our door anymore,” says Grogg, “and then saying ’Come and get it.’ “

That’s great, and all to the good of the budding Dallas film industry. But I’ll still miss the brothers from Brooklyn.